The Only Hope—Judy Garland

Can Judy Garland—whose attempt at suicide by slashing her throat with a jagged glass put her on the front pages—ever come back? I think so.

However, she must make the fight herself. Unless she does this, even those who love her best cannot help her.

At twenty-seven, when her life and her career should be at its brightest peak, she faces the need to give up everything she holds dear and put herself in the hands of wise psychiatrists. Her battle back to mental and physical health must be made in a world of strangers—men and women in the white armor of the medical world.

It won’t be easy, the long fight ahead. But she can take courage in the knowledge that others, some of them her friends, have waged battles just as difficult—and won.

Robert Walker spent months and months at Menninger’s Clinic near Kansas City where his tired nerves were healed and his bitterness against the world forgotten. Bob, too, knew what it meant not to be able to make pictures, not to be able to live his normal life. But because he had indomitable will he proved that it is possible to win a losing fight with yourself.

Twenty-five years ago, I also had a battle to wage. Out of the blue, when tuberculosis struck me down, I had to leave my bright world and go into retirement among strangers. But that terrific fight to live, when death would seem almost welcome, pulled me through—and soon I forgot those black months away from home and loved ones. Judy can know this wonderful triumph of the spirit too.

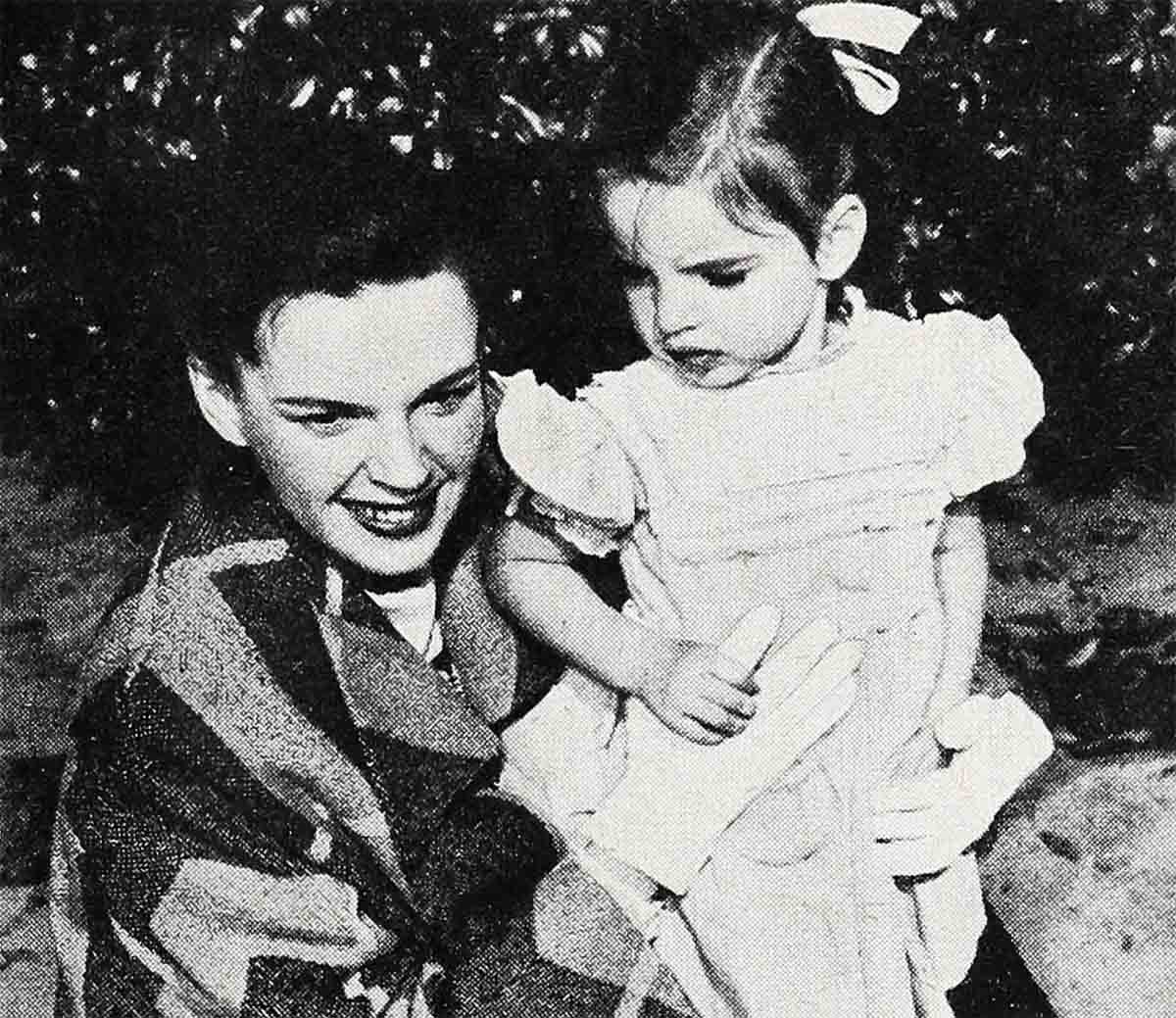

How did this girl ever get herself into a place where death seemed preferable to life? Surrounded by everything wonderful—a devoted husband, a wonderful and talented little girl and a world of friends—let me repeat, what can possibly have brought her so close to the precipice of personal ruin?

Some of her friends say she has worked too hard from the time she was twelve years old, when as little Frances Gumm of a sister act, she first attracted the attention of Louis B. Mayer and was brought M-G-M as a child star. These friends argue that she never had the proper rest or diet in her formative years, and that she is the victim of her sensationally successful career.

Judy, herself, likes to believe it is this early childhood effort and strain that has caused her complete breakdown.

But many disagree. Child actresses on the motion picture lots are sent to school and permitted by the courts to work only a certain number of hours.

At the time Judy was taken out of “Barclays of Broadway” because of “temperament,” she told me she had worked since she was a little child, that she was worn out, and needed a rest which had been denied her.

Judy’s mother, at that time, was vastly annoyed. Judy had led a normal, carefree, happy childhood, her mother insisted. Her father had been a well-to-do theater owner and Judy had begun her career of singing and dancing because she loved it—and not because she had to support her parents.

Another theory is that Judy has been physically ill for almost ten years, ever since she reached maturity, and began taking sedatives to relieve physical pain.

But one thing I shall never in the world believe is that Judy was driven into her condition by a hard-hearted studio forcing her to work beyond her endurance!

Next to Vincente Minnelli, if Judy has one true friend in the world, it is Louis B. Mayer. It was “L. B.” who comforted her when it was necessary to take her out of “Annie Get Your Gun.” It was “L. B.” who financed her trip to a Boston sanitarium. He not only paid the complete expenses for what he was sure would be a “cure” for her—he also paid those of her agent and friend, Carlton Alsop.

Always Mr. Mayer has loved Judy and advised her like a father.

I was at his home one night at dinner when he was called away by a sudden telephone call. It was not until weeks later that I learned (and not from him) that he had been summoned to hysterical Judy’s bedside. She would not be calmed until the man who made her a star came and sat with her and told her that she was not “through”—and that pictures were already in preparation for her when she recovered her health.

It was L. B. who soothed her to the point of her decision to go East for treatment under the care of fine doctors.

When she returned—after three months—everyone was so happy because she seemed to be herself, glowing with health and happiness and added weight.

Once again she went to parties and had fun. Almost every Sunday night I would see her at the popular La Rue cafe holding hands with Vince and looking for all the world as though she had not a care or a problem on her mind.

Far from being forced back to work against her will, she was actually begging M-G-M to put her to work. “I’ve worked all my life,” she pleaded with them. “I’m restless being idle.”

And, believing her, they put her to work in “Summer Stock.”

Almost from the beginning, it was obvious that a mistake had been made. But everybody from the bosses down “covered” for her. Halfway through, everyone connected with the picture realized that the trip to Boston had not cured her.

As she grew more and more pitifully nervous, it was decided to send for Professor Rose, the man who had done so much for her in Boston. He stood by during the final weeks of the picture so she was able to finish it.

Judy had promised the psychiatrist that she would return with him to Boston. But at the end of the picture she begged Vince Minnelli not to send her.

Poor, loyal Vince. He may have known that Judy should go back to a hospital. But he loves her so much he cannot bring himself to do anything that makes her unhappy.

She coaxed him into going with her to Carmel where she promised to rest—and she did. In fact, she was coming along so well that when June Allyson had to be replaced in “Royal Wedding” because she as a possibility.

“Do I want to do it?” she almost yelled over the telephone. “Oh, making another picture with Fred Astaire (their ‘Easter Parade’ had been sensational) is the best medicine I could have.”

But everything still depended on the decision of the doctor. Impressed by Judy’s happiness and the big improvement in her health, he gave his okay.

The picture was still in the rehearsal stage—had not even gone into production—when the same old routine started all over again . . . Temperamental words with the producer . . . Being late to rehearse with Astaire . . . Finally, not sho ing up at all . . .

Those who knew anything about the situation were aware that Judy’s not showing up for an hour’s work was not the real reason for her third suspension, news of which I broke on my radio show.

Fred Astaire, the kindest man in the world, was a nervous wreck himself before Judy was removed from the picture. Her emotional outbursts and hysteria had caused Charles Walters, who had directed “Summer Stock,” to ask for his release from “Royal Wedding.”

But even those close to her did not know how deeply sick she was until that black Monday night when she rushed into the bathroom of her home during a business conference—and slashed at her throat.

Unfortunately the story got to the papers, when someone close to Judy talked at one of Hollywood’s night spots.

Sorry for her impulsive act? Of course She cried and cried in Vince’s arms.

We all are sorry for her—to the point of heartbreak. But one thing is vitally clear—by this action she has proven that she can no longer control herself.

As heartaching as it may be to Vince he must let her go away for a long time forget Hollywood, forget career, forget him and the baby—until she can come back well and happy again.

As we go to press things seem brighter certainly. For again Judy called her friend, L. B. Mayer, and asked him to come and see her. He told me himself he was delighted with her condition. Her eyes were bright. She was alert. More than anything else in the world, she told him, she wanted to get well. Whereupon Mr. Mayer telephoned Nick Schenck, another M-G-M executive, and it was agreed Judy would be paid by the studio until she is well again. Also the possibility of her starring in “Show Boat” was discussed—if she is completely recovered when this picture starts in the fall.

Judy’s ready to face facts, it seem. She’s going to turn down the offer to go to London for an engagement at the Palladium. She’s going to make the fight that she must make if she’s to be wholly well again.

It could be, as Mr. Mayer says, that this recent tragedy was a blessing in disguise because now Judy knows what can happen if you let yourself go too far.

THE END

—BY LOUELLA O. PARSONS

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1950

vorbelutrioperbir

17 Temmuz 2023I’ve learn a few just right stuff here. Definitely price bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot attempt you place to make one of these excellent informative site.