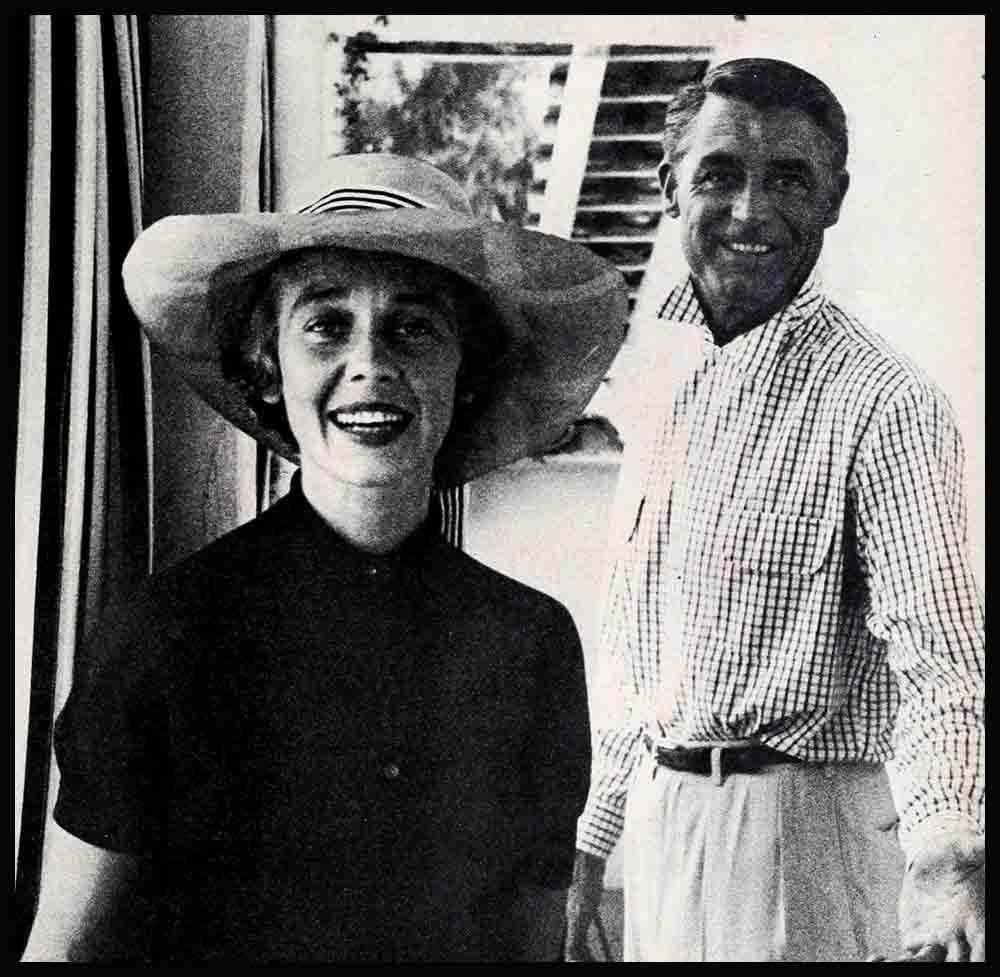

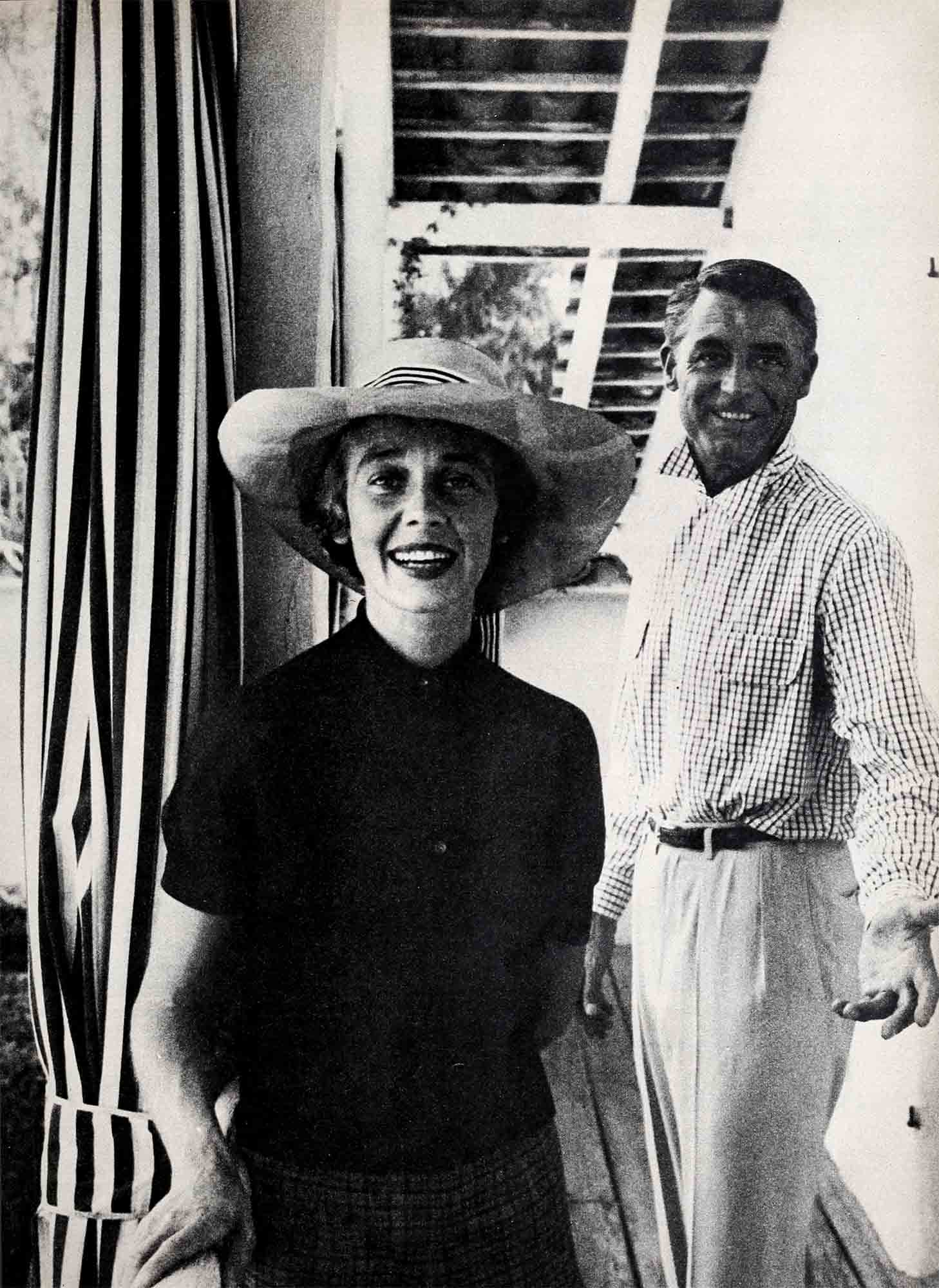

“We’ll Always Love Each Other But . . .”

Five minutes. Five minutes on a brilliant August day in 1949. Long enough to tell a story, watch a sunset, buy a handful of flowers. Long enough for Cary Grant and Betsy Drake to fall in love.

And nine years later, on an October day in the middle of a Hollywood heatwave, they insisted they were still in love. But in the next five searing minutes, they sat here together and composed an epitaph for their marriage.

Cary Grant fell in love in five minutes with a plain little girl he didn’t know, who wore horn-rimmed glasses and sensible shoes. He fell in love with her in a ship’s dining salon through which Elizabeth Taylor had walked not five minutes before, in which Merle Oberon sat chatting across the table from him.

AUDIO BOOK

For a few minutes he saw not one of them. He saw only Betsy Drake.

What was to happen after that neither of them could possibly have imagined. . . .

The Queen Mary was five days out to sea. Cary Grant was on his way home from a holiday in England, where he was born. He had been renewing old friendships—and forgetting the newest of his bad memories. But in forgetting, he could not make them disappear. He smoked too much and drank too much. He stayed up too late at night and had too much trouble falling asleep. He was tired too often.

It had been like this since the first serious mistakes. Twice he had married for love—and twice he had lost. Now he could look back and admit, “I married lovely women. But I was an idiot and a boor. I deserved to lose them.” But hadn’t the knowledge come too late? Too late to save his marriage to lovely, delicate Virginia Cherrill, who had laughed off hundreds of his escapades but who, one day, couldn’t laugh any; longer. Too late to save his marriage to Barbara Hutton. He had loved her, too.

For two long years he had lived in the hope of making her his wife. She had been hurt in the past—her fantastic fortune had brought her more grief than joy. He was going to make it up to her, all of it. For two years he talked, telling her how wonderful it would be.

Finally, she said yes.

She married him in 1942 and the gift of gab that had won her love was what drove her finally away. The truth of the matter was that Cary was too clever for his own good—or anyone else’s. There was no conversation so serious, no subject so delicate that his quick tongue failed to find an opportunity for a pun, a jibe, a pointed joke. He couldn’t help it; it was the way he was used to talking. But he had married a woman too sensitive to laugh when the barb went deep. Time after time she was reduced to tears; time after time he would pull himself up, furious at himself and at the world.

“Why did someone like you ever marry me?” he would shout.

But he couldn’t stop, and eventually Barbara left him, too.

Not good memories, but, at least, on this brilliant day in August, 1949, they were far behind him. The trip to England had been fun and wasn’t that what he was most interested in? He’d been to the theater a lot; the biggest impression had been made on him by a little American actress he’d never heard of, Betsy Drake, playing the lead in “Deep Are the Roots.” She wasn’t beautiful but she had a glow and she played the difficult role with grace and intelligence. “Talent there,” Cary had remarked to a friend and then forgotten all about it.

Sailing day had come at last; the Queen Mary was waiting. His pals treated Cary to a farewell champagne luncheon. None of them was feeling any pain when they piled into a convertible and headed for the dock.

But for Betsy Drake, also sailing for home on the Queen Mary, life was not so much fun.

She didn’t really want to go home. It had taken her years of desperate struggle to get anywhere in the theater—and now her first big role was finished. Her parents had been divorced since she was a child and she had no home, no people, really, to return to. Just another dreary year of job-hunting with her clippings under her arm. She was all worn out and it wasn’t a pleasant prospect. Besides, she had a toothache, a perfectly terrible pain that swelled her jaw and destroyed the fun of the ship’s sailing.

The first glimpse she ever had of Cary Grant off a movie screen was when she was standing on deck and Cary’s convertible pulled up to the customs’ shed. What she saw was a slightly high-looking young man, surrounded by friends, roaring with laughter, lifting his suitcases out of the back of the car and dropping them in again. For an instant, she had wished she were a part of them, having fun. Then her tooth throbbed and she turned away. “As far as Betsy Drake is concerned,” she thought, “this trip is going to be one long, dull rest.”

And it might have been if, two hours later, as the ship got underway, she hadn’t had to pay a visit to the purser’s office. In her sensible flat-heeled shoes and brown dress, she walked down the corridor just as Cary Grant pushed open a door and walked in on his way to join Liz Taylor and her mother for lunch. The ship, leaving the harbor, lurched violently, Betsy staggered and was pitched against the wall with one arm above her head, the other at her hip—a perfect cheesecake pose. Cary grinned, then recognized her. “Hey, I saw you in ‘Deep Are the Roots.’ You’re . . .”

Her face burning with embarrassment, Betsy marched right past him. Later, telling about it, she told reporters she hadn’t heard him say a word. Later, denying it, Cary maintained she deliberately cut him dead. At the time, all that mattered was that Betsy Drake, nobody from nowhere, slammed the door of the purser’s office right in Cary Grant’s face!

He spent the next three days looking for her.

And without success. Betsy, nursing her toothache, and her humiliation at being practically thrown into the arms of a movie star the first day out, wasn’t budging from her cabin.

But on the fourth day, she came up for air. She walked to the deck and stood leaning over the rail, watching the waves. Actually, nothing could have kept Betsy Drake down for long. She stood on deck a minute, then decided on a walk. Walking was—and still is—her favorite sport.

A dozen yards away, down the deck, Cary spotted her and his eyes lit up. He was standing at the rail, talking to Merle Oberon; now he nudged her. “Merle—there she is. That’s the girl.” Merle turned and looked. “Fine. Now go introduce yourself.”

Cary nodded, grinned, took a step—and the grin faded. He had never been shy with women, except once before. . . .

One morning at the studio he had been called to the phone. It was house guest Noel Coward ringing up from Cary’s home. “Cary? I’ve invited Greta Garbo to tea this afternoon. Try to get home in time to meet her, eh? She’d like to be introduced . . .”

When Cary put the phone down, his hands were shaking. By mid-morning he had realized the truth: Garbo, with her incredible beauty, her talent, her aloofness, was such a legend to him that he was afraid to go home to his own house and meet her. Noon came and he told himself not to be a fool, that it would be wonderful to be introduced to someone he respected and admired as much as he did her. But he couldn’t budge. All afternoon he invented things that had to be done, to keep him at the studio.

It was dusk when he finally pulled up to his driveway. He walked in—and there in the living room, standing up, ready to leave, was the fabulous Swede. Noel smiled happily. “Greta, I’d like you to meet Cary Grant . . .”

Cary opened his mouth—and nothing came out. In wordless silence he shook hands with his guest, he bowed. Garbo smiled, said she was happy to be there, asked a question, waited, stared at him, asked another, remarked on the weather—I and finally gave up.

Cary had still not said a word.

Bewildered, Noel escorted Garbo to the door. Miserable, Cary trailed after them to Garbo’s car. And there, at long last, he found his tongue.

“Very pleased to meet you,” he burst out to his departing guest. “How dod you do?”

It became a running gag among Cary’s friends: for once he had been tongue-tied, stricken dumb by admiration and awe. . . .

“Cary, Cary . . .” Merle’s amused voice brought him back from his reverie.

“Look,” he began haltingly, “it’s like this. I don’t want her to think I’m picking her up. You know.”

Merle stared at him. “Well—?”

“Would you go talk to her for me? Ask her—ask her to have dinner with us tonight. Tell her—at the captain’s table.”

“But I don’t know her,” Merle wailed. “I never met her!”

“That’s all right. Go on. You’re a woman, you can do it.” He paused. “If she doesn’t want to—you might try telling her—it’s the captain’s table.”

Merle’s mouth dropped open. Cary Grant, cocksure, debonaire, lady-killer Cary not only afraid to talk to a girl, but afraid she’d need more inducement than just his name to join him for dinner. She almost laughed, but changed her mind. Without another word, she headed down the deck towards Betsy.

When she got there, of course, she was embarrassed.

“Excuse me. Hello. I’m—I’m Merle Oberon, and a friend of mine . . .”

Betsy whirled—and stared. “Of course, Miss Oberon. I recognize you . . .”

Merle blushed. “Yes, well, Cary Grant is a friend of mine and he, he was wondering if you would join us for dinner tonight. At—at the captain’s table.”

Betsy’s lips parted slightly. If there had been a chair, she would have flopped down into it. Finally she said slowly, “I don’t have an evening dress with me . . .”

“Oh,” Merle said. That did it. Evening clothes were absolutely obligatory in the formal dining salon—and everyone in the room stared at the captain’s table, the place of honor. No woman would be caught dead there without her best gown. She’d be glad to lend Betsy something but they weren’t the same size at all. “Well,” she stared.

Suddenly Betsy smiled. It was more than a smile, it was a grin. It brought with it the glow that had lit her performance on the stage, that seemed to light up her entire life.

“Tell Mr. Grant I’d be delighted.”

That night Cary was at the table early. He sat there with Liz Taylor and her mother a few seats away, with Merle across the table. His evening clothes were, of course, faultless. He kept his eyes constantly on the door.

And then he saw her.

She walked into the dining salon with her brown hair brushed to a shine and parted neatly on one side. She wore a plain black street-length afternoon dress, ! and black shoes. She wore no jewelry because she didn’t own any. The side of her face was puffy with toothache, but she was smiling.

She walked right across the room with every eye following her, and her head was held up, and proud. She never wavered.

Cary Grant, standing up at his chair to receive her, thought it was the bravest thing he had ever seen in his life.

She sat down next to him. Her voice was the husky voice he remembered from the show, her smile lit up the entire room.

It only took five minutes for him to realize that he was in love with her. Only five minutes because it was so obvious.

The rest of the voyage passed in a daze. The only thing Betsy Drake remembers of it was that Cary, elegant Cary, put his evening suit in his trunk and went down to dinner every night by her side in a business suit, to keep her company. Maybe that was why she fell in love with him. Or maybe it was because of what no one else had seen, but she saw so clearly: the deep, basic honesty that the quips and the bright talk attempted to cover.

Like when he asked her to star in his next movie with him.

“It’s called ‘Every Girl Should Be Married.’ The part is perfect for you.”

“They’ll never give it to me,” she said

“I’ll make them.”

“Oh, you can’t. They’d say you were doing it because you—you like me.”

“They won’t say it after they’ve seen you act. And maybe they’ll be a little more perceptive. Maybe they’ll say—because I need you so.”

Was it possible that no one had seen that side of him before? Or was it more likely that it had never been there—until Betsy came along.

Whatever it was, they made the movie together, and they were a hit. When they were done with it, they were more in love than ever.

Cary would drop over to Betsy’s tiny Hollywood apartment and find her, glasses on her nose, poring over a book.

“What’s that about?”

“Spiders.”

Cary would gasp. “What on earth are you reading about spiders for?”

“They’re interesting. Here.” She would reach over to a stack of books piled on the floor. “Here’s another one on spiders. Go ahead, look.”

“I don’t want to read about spiders, for heavens’ sake. I thought we’d go dancing.”

But Betsy, deep in her book, would scarcely hear him. Cary would wander around the room disconsolately; finally, bored, he’d pick up the book.

An hour later, Betsy would nudge him. “Hey, I asked if you want a cup of coffee.”

Cary would look up, blink. “Coffee? Oh, ah, sure. Sure. As soon as I finish this chapter.”

To his amazement, he found himself reading more and more. He went through Betsy’s entire library finally, fiction, nonfiction, travel books, science—everything.

“Is there anything at all,” he asked her one day, “that you’re not interested in?”

She thought it over. “Nope, I guess not. How about you?”

“I thought there were a lot of things,” Cary said thoughtfully. “But I guess I was wrong.” He looked around. “Betsy, how did you ever find time to read so much, do so much?”

“I guess,” she said slowly, “it was because I was alone.” She looked up, and the wonderful smile broke out. “Now, for the first time, I’m not alone any more . . .”

As much as she gave to him, he gave to her. Knowledge of how to dress, how to do her hair, how to talk to people—all the things she had never had time to learn, he taught her. With Cary beside her she was no longer plain. Her friends discovered to their surprise that little Betsy was pretty after all. No, not exactly pretty. Beautiful was more like it.

What she did for Cary’s soul, he did for her poise. In both cases it was an undreamed-of blessing.

They were married on Christmas Day, 1949. It was that day because it was the one out of all the year when Cary’s closest friend, Howard Hughes, could be reasonably sure of not being tied up with business. To keep the wedding private, they told no one but Howard, drove out to an airport in a borrowed car, climbed over a back fence onto a runway, and were picked up there by Howard in a Constellation airplane. They landed in a deserted field in Arizona and were taken to a farmhouse to be married. The minister had no idea who was getting married, and cared less; to Betsy and Cary it was perfect. To Howard Hughes it must have been somewhat nerve-racking because, in perfect best-man tradition, he dropped the wedding ring and he, Cary and Betsy had to crawl around on the floor looking for it while the minister tapped his foot.

When it was over, Howard phoned RKO to tell them, kissed the bride and drove them back to the airport As they got out of the car, they saw a group of people waving to them from the hangar “The press,” Cary groaned, and turned to run But it wasn’t the press. RKO had sent the news out on the radio via a special bulletin. A cowboy who had seen the huge Constellation land put two and two together, gathered up his friends, and brought a bottle of champagne to toast the newlyweds.

It was a gloriously happy moment.

They came home to a house and garden in Beverly Hills, to dozens of lavish presents, hastily bought by their friends (the most expensive came from Barbara Hutton), to a host of reporters—and to the gossip.

“That little nobody! Imagine her getting Cary Grant!”

“Don’t worry, she won’t have him long. If Barbara Hutton couldn’t keep him, nobody could. Just wait till she starts to run into his past all over the place. . . .”

There wasn’t long to wait.

One of their first guests was Countess Dorothy di Frasso. Cary, introducing her to Betsy, took a deep breath and said in a rush: “It was Dorothy, you know, sweetie, who introduced me to Barbara.” It had to be said, because in any conversation with Dorothy, Barbara would pop up—they were such close friends. But because it had to be said didn’t mean that Betsy had to like it. Cary watched her hazel eyes open wider, and wondered anxiously. She would be polite, no doubt. But afterwards would she tell him to keep his former wives’ old girl friends out of her house and her life? She would, of course, have every right.

But the look in the brown eyes was not anger but honest interest. “How do you do?” said Betsy Drake Grant. “I’d like to meet Barbara myself, you know. She sent us such a beautiful gift . . .”

And only a few years later it was Betsy, at Cary’s side, who performed the last, greatest act of friendship for the Countess. Dorothy di Frasso died alone in Hollywood, and the night before her funeral, when the curious and the sad had finished paying their respects to the body, it was Cary and Betsy who walked into the mortuary and kept vigil through the night beside the coffin.

“She hated to be alone,” they said then, simply. And so the two of them, their faces pale in the dimly-lit, flower-banked room sat all night long and tried to talk and laugh, so that Dorothy would know she had friends with her—always.

But Cary’s past was to come even closer than that. There was the time he put down a telephone and turned to Betsy to say: “I—uh—just spoke to my son. He’d like to come for a visit. . . .”

“Your son?” Betsy said, astounded. “Cary, you haven’t got a son!”

Cary turned slightly purple. “Oh, of course. I mean, my—my step-son.”

Betsy’s voice was even more bewildered. “But I haven’t got a child, so how can you have a step-son? What on earth . . . ?”

“I’m putting it very badly,” Cary sighed. “What I mean is—I know it’s a lot to ask of you under the circumstances, but—it’s Barbara’s son Lance. He wondered if he could stay with us a while. We—we used to be very close.”

It was a lot to ask. But Betsy, looking at her husband, saw deeply as she always did. Saw how much Cary wanted them to have children of their own. how deep the hurt had gone when it looked as if there wouldn’t be any.

“Of course,” she said softly. “Ask your son to stay with us as long as he likes.”

Of course, not everything was perfect, not right away. There were the little things. Reading was not Betsy’s only hobby: she wrote, she painted, she swam. Shortly after their marriage she decided to take up photography. As with everything she does, she threw herself whole-heartedly into it. Within a week, their honeymoon house was bursting with cameras, flash bulbs, light meters. On literally every chair were stacks of manuals about picture-taking. Cary, stumbling for the fourteenth time over one of eight tripods, finally lost his temper.

“Betsy, you’ve got to find a hobby that doesn’t take up so much room! Why don’t you learn how to write on the head of a pin?”

And there was the time that they shocked Hollywood by telling a reporter calmly that they not only had twin beds but separate rooms!

“Cary believes in it,” Betsy said blithely. It would have been too hard to explain that he was just now, under Betsy’s guidance, learning that being alone for a while could do wonderful things for a man, that he had to have a place now where he could shut a door and be completely alone with the new personality emerging from himself. In the storm of interest the separate rooms aroused, a dozen reporters appeared at the Grant house. Betsy, remembering all the things Cary had told her about courtesy-at-all-times, tried to be polite. Finally it was too much and she threw caution to the winds.

“How much do you charge for your magazine?” she demanded of the writer.

“Fifteen cents.”

“Well, for fifteen cents, nobody gets into our bedroom!”

These two people had found so much within themselves, with each other that, at first, they really didn’t need anyone else. To those whom they loved, Dorothy di Frasso, Lance, Ingrid Bergman, the Stewart Grangers (they were god-parents to little Tracy Granger) they were friends for a lifetime, friends far beyond the ordinary run. But for the world at large— they were too busy being together.

And there was nothing they didn’t do together. They went on health kicks together; for a while they lived exclusively on a Vitamin C thing called “Rose Hips.” When Betsy took up writing instead of acting—because it left her free to be with Cary he insisted on reading her every page. “Then he would tell me exactly what was wrong with it. I would get furious, rave and rant—and then when I calmed down I’d know he was perfectly right. He’s a perfectionist, that’s all.” So successful has the collaboration been that Betsy today is a top TV writer (she uses pseudonyms) and, though she denies it, some of her friends credit her with having written the script of Cary’s new picture, “Houseboat.”

And the togetherness went deeper than that. “I’m sick and tired,” Cary said recently, “of being questioned about why I look young for my age and why I keep trim. Why should the idiots make so much of it? Why don’t they emulate it, rather than gasp about it? Everyone wants to keep fit, so what do they do—they poison themselves with the wrong foods, they poison their lungs with smoking, they clog their pores with greasy make-up, they drink poison liquids.

“What can they expect?”

Pretty strong talk for a man who admits that, only a few years ago, he was a chain smoker and a frequent social drinker. How did the change come about?

“Betsy hypnotized me. Literally. She studied up on hypnotism, and when I decided to give up smoking, she tried it out. She put me into a trance and planted a post-hypnotic suggestion that I would hate smoking. We went to sleep and, the next morning, I reached for a cigarette, just as I always did. I took one puff—and instantly I felt nauseated. I didn’t take another that day, and I haven’t had one since.”

Nor does he over-eat, over-drink, or gain weight any more.

“I have only one vice left. Making love to my wife.” He would grin at you. “I recommend love.”

“She is the only person in the world who has ever belonged entirely to me,” Cary had once said of Betsy. “I love her so much that—words fail me.” But after nine years, Cary had to face the reality of a marriage that had ceased to be a marriage. Betsy might belong to him, but she couldn’t be left to wait alone for him in the unfeeling manner of a possession. He couldn’t be that selfish to anyone he loved that much. He had to set her free.

“As far back as I can remember, I longed for a home of my own. for roots,” Betsy had once said. “All my life I never had any until I met Cary. . . .” She’d given up her acting career and turned to writing, a lonely, solitary profession, so that her career wouldn’t conflict with Cary’s career or with their marriage. Now, after nine years, she could pace the empty halls in the tragic knowledge that she still had not found the home she longed for so deeply. She knew that Cary would welcome her along on his many trips to make pictures in Spain or England, in France or Italy, or on his promotional tours throughout the States. But this, too, was not her way of life. She would go back to acting—at least until she found that true home.

“We have had, and shall always have, a deep love and respect for each other,” their mutual statement read. “But, alas, outmarriage has not brought us the happiness we fully expected and mutually desired. So since we have no children needful of our affection, it is consequently best that we separate for a while. . . . There are no plans for divorce. . . . We ask our friends to be patient with, and understanding of our decision.”

They made the statement, each with a deep desire for what was best for the other. They smiled, each brave for the other, at their last time together for . . . for how long?

It was as simple as that. A glamorous man with an unhappy heart. A plain girl who had been lonely all her life. Love brought them together once—and though they are parting almost for love’s sake, it may bring them together again.

THE END

YOU’LL ENJOY CARY IN M-G-M’S “NORTH BY NORTHWEST” AND BETSY IN 20TH’S “INTENT TO KILL.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1959

AUDIO BOOK