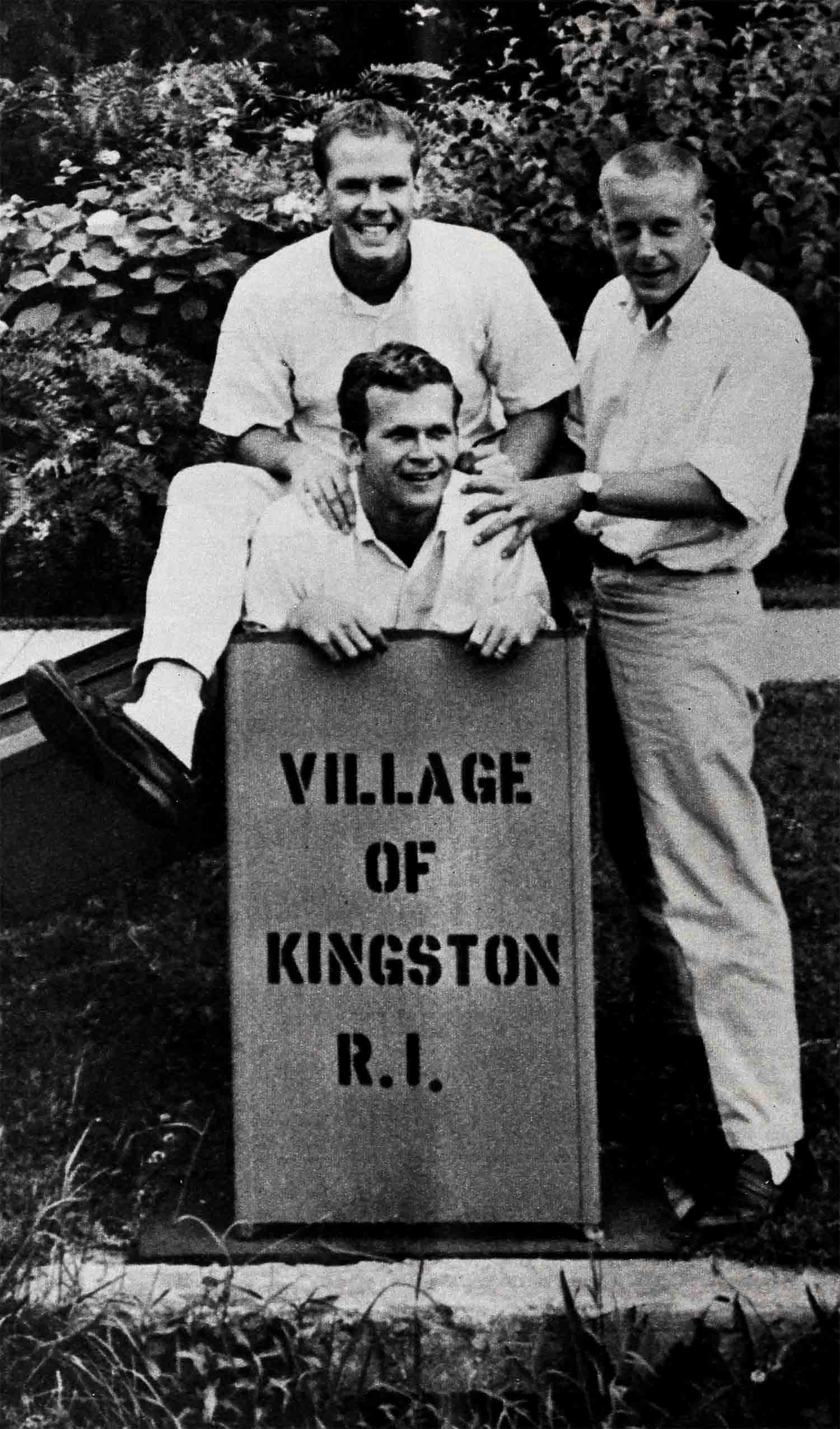

Village Of Kingston

The noise of the hotel coffee shop with steady sounds of the lunch-hour crowd, the waitresses ordering and the clink of china, didn’t seem to bother Nick Reynolds as he sat, hunched over a round marble table, examining timetables spread out before him.

He checked the time on his wristwatch, then began noting figures on a small white pad. He didn’t even notice when Dave Guard and Bob Shane, who were his partners in the Kingston Trio for the past four years, since they left college, came in and sat down across from him.

“What’s the score?” Bob asked.

Nick double-checked his figures before looking up. His face relaxed into a broad smile. “Only six days, five hours and . . .” he glanced back at his watch, “. . . fifteen minutes—if the plane’s on time—”

“ . . . before he sees his wife again,” the fellows said together and the three of them laughed. “Hey, by the way,” Bob said, “Don’t forget to mail that card we bought back in Rhode Island.”

The waitress arrived with his coffee and Nick scooped up the folders and tucked them in the pocket of his sports jacket. He knew that later that night in his hotel room, he’d probably consult them again—just to make sure nothing would go wrong.

“It puts my jacket out of shape—these timetables,” he’d once told his wife, “but there’s nothing, Honey, I wouldn’t do, and little I haven’t done,” he added, “to save a couple of hours and get home to you a little earlier.”

They all felt that way. Being separated from their wives is murder. When they were doing their show in Washington, D.C., they had a break between two appearances. Bob, who had been married about two months, was so lonely, he grabbed a plane home, traveled over a thousand miles, spent three hours with his wife and was back in time to go on with the next show.

Another time, they were doing a series of personal appearances in New York with a recording session tacked on at the end of their schedule. They worked straight through the night and when the album was finished it was close to six o’clock in the morning.

They were already half-asleep as they fumbled into their coats. Then Dave pulled out his airlines’ schedule and discovered there was a jet flight to San Francisco at 8 a.m., ten full hours earlier than the flight they had reservations for.

Grabbing their guitars, they rushed out of the studio and to the hotel, threw their clothes into their bags—drinking black coffee the whole time to keep awake—and got to LaGuardia Airport with only minutes to spare. There was just time to send off one telegram to Gretchen Guard announcing: “On our way. Tell Joan and Louise.”

All three couples now live conveniently within fifty miles of each other in Northern California—Dave in his old college town of Palo Alto, Nick in Sausalito and Bob in Tiburon.

“It helps cut down on the overhead,” Dave explained. “Usually when one of us phones home, we pass messages back and forth for the other two wives.” He paused; then, with a quick look at the others, admitted: “Anyway, it’s supposed to work that way.”

Alone in a hotel room

“There’s something about being alone in a hotel room that really drives you to that phone,” Bob said, with a bewildered shake of his head. “And if the circuits are busy or I can’t get through to Louise right away, I feel the world’s against me,” he added, remembering the time the Trio arrived in New York for a rare three-day stopover.

As soon as Bob checked into his room at the Park Chambers, he automatically reached for the phone. The emptiness of the hotel room closed in on him as he waited for the operator to put through his call to Louise in Atlanta, where she was staying with her folks.

He lay back on the bed and imagined how she would look as she answered. Instead he heard a soft, drawling voice—it was Louise’s mother—telling the operator that Mrs. Shane and her cousin had left only a few minutes earlier to see a movie. Dejected, Bob left word to have her call him when she got in and went to dinner.

When he returned to his room later, he tried to write Louise a letter, but gave up. She could always tell when he was depressed and he didn’t want to make her feel worse. After all, being separated was hard on her, too.

He was deep in a daydream about Louise, when the telephone rang and he tripped over the desk chair rushing to answer it on the first ring. But it was only Nick, telling him to come right over to the Blue Angel Supper Club where he and Don MacArthur were discussing some commitments.

It sounded urgent so Bob left word at the desk where he would be if the call came in and took a cab to the club. As he walked toward Nick and Don, he noticed that a girl was sitting with them. It was dark in the room and she had her back toward him but he could see that she had long, blondish hair.

“Hey, who’s the girl?” he asked Nick who came to meet him.

Nick looked at him quickly, then tried to hide his smile, but at the sound of Bob’s voice, the girl turned around. Nick couldn’t keep silent any longer.

“Man, that’s no girl . . .” he burst out with a loud laugh, “that’s your wife!”

Bob just stood, without saying a word, and stared, even after Louise came over to him. Finally, he managed to stammer: “It . . . really is you, isn’t it.”

Later, after he had recovered, Louise told him that, when she found out he would be in New York for three days, she decided to surprise him and fly up. She arrived at the hotel while he was out and that’s when she and Nick arranged the meeting at the Blue Angel.

“You know, even after Nick said it was my wife, I wasn’t sure,” Bob admitted sheepishly afterward. “Louise had changed her hair style and had it streaked with blond since I last saw her.” After a minute, he added: “It’s frightening how people can change when they don’t see each other every day.”

“That’s the hard part,” Dave said thoughtfully, “trying to maintain some sort of communication with your wife when you’re apart so much. I guess we’ve each devised our own way of trying to share things with them . . . even when we’re not together.”

Bob spends his free hours shopping for charm bracelets that memorialize places he and Louise haven’t been together and experiences they’ve never quite managed to share.

“When we played Washington, I sent her a bracelet with an engraving of the Washington Monument,” Bob remembered. “And when we played the Blue Angel, I sent her one with little blue bugs playing on a pipe. I don’t want her to forget who I am,” he murmured, almost to himself.

“I don’t know what I’d do without these letters,” Nick smiled, tapping his breast pocket where he always carries the latest one. “Joan puts down her innermost thoughts, and I read them over and over.”

Can they ever make it up?

Both the fellows and the girls have tried to accept the phone calls and letters as substitutes, but each of them knows that nothing can ever make up for those days, lost forever, that they didn’t spend together. And some of their most cherished memories, even more precious because so brief, are those unexpected minutes they had together.

Like the time during their midwestern tour last fall when the Trio received a last-minute call to fly back to Hollywood to record some soft drink commercials. The recording session took up the whole time, with only three stolen minutes for a hurried call home, and the next morning the boys were back at Los Angeles Airport for their flight to Chicago. They were having their tickets checked at the gate when Nick suddenly shouted: “Hey, Dave, look.”

Dave turned and saw Gretchen, her brownish-blond hair catching the early morning sunlight as she ran toward him.

“What’s wrong, Honey?” he called, rushing to meet her.

She was out of breath and and could only shake her head to reassure him.

“Well, then, what are you doing here?” he asked in a puzzled voice.

“Oh, Dave, you haven’t forgotten, have you?” she said, her voice catching a little in disappointment. “It . . . it’s my birthday.”

“Of course I didn’t forget,” Dave assured her and bent to kiss her just as the final boarding warning sounded over the loudspeaker. Quickly, he said: “Happy birthday, Honey. Sorry . . . but I’ve got to get on the plane now. It was great seeing you,” and he hugged her again. “ ’Bye now. See you sometime.”

He started running across the airfield, then stopped, turned and called back: “You mean, you didn’t get your present yet?” And, almost shyly, he added, “Hope you like it.”

Gretchen stood alone on the field, waving hard until long after the plane had disappeared. The gift came the next day.

On Nick’s and Joan’s first anniversary, Joan flew in from San Francisco to be with her husband, even though she knew he would be working the whole time.

At three-thirty in the morning, the boys were still recording and Joan had fallen asleep on top of the piano.

“A great way to spend an anniversary,” Nick muttered and tenderly covered her with his coat.

A minute later, the studio door swung open with a sharp bang. At that signal, Dave and Bob sounded a loud fanfare and Don MacArthur and Louise Shane, who had flown up to join Bob, marched in carrying one pink cupcake with a frosted candle burning in the center. Everyone burst out singing: “Happy anniversary to you . . .”

Joan blinked sleepily, her yawn slowly turning into a smile. “Isn’t this a beautiful anniversary?” she whispered to Nick as he lifted her down from the piano, then buried her head in his shoulder and started to cry.

“It sure is,” Nick said softly, smiling down at the top of her head. “The greatest,” and he gently brushed away her tears.

At the time, just being together seemed pretty wonderful but Nick, Bob and Dave all realize that those few snatched moments aren’t enough to make up for the lonely, frightening experiences their wives have to face alone.

“I felt so helpless”

“I feel I have an extra responsibility to be an understanding husband,” said Nick, who met his future wife while she was appearing in a night club a few doors down from the Hungry i, where the Trio was singing.

“Joan’s a good comedienne,” Nick said proudly, adding with a smile, “and one of the prettiest ones I’ve ever seen.” Bob and Dave nodded in agreement. “And she gave it all up to marry me. She knew our marriage couldn’t work if we were both on the road. I feel I have to make that up to her.” He paused. “I felt so awful when she was expecting our baby and I couldn’t be with her. I knew that was when she really needed me.”

He brushed back a tuft of brown hair that immediately fell right back down over his forehead and stared solemnly at the table. He wasn’t clowning around now. “I did call Joan every day,” he said, as though still trying to reassure himself. “Sometimes more than once. She’d try to be gay and happy but after a couple of minutes her voice would go shaky and she’d have to hang up. She didn’t want to, but she couldn’t help it. It was weird.” He let out a deep sigh. “I felt so helpless. I suppose talking on the phone helped some, but it wasn’t enough. That was one time when I should have been with her. . . .”

When the baby was actually born, though, on March 31, 1960, Nick was at his wife’s side. Gretchen Guard wasn’t as lucky. Her second child, a boy, was born on April 21st while Dave was in New York recording an album for Capitol Records. The same thing had happened two years before when their daughter, Catherine Kent Guard, was born.

“We were playing the Blue Angel in New York at the time,” Dave remembered painfully. “I really sweated out the waiting but when the baby was ten days late, I felt, ‘If it hasn’t come by now it never will.’ I just tuned myself out.”

Like any normal father-to-be, Dave wanted to be with Gretchen, holding her hand until the last minute and nervously pacing a smoke-filled hospital waiting room. Instead, he sat alone in his hotel room in New York and thought about her. Usually he read a book a day to pass the time but that evening he couldn’t concentrate and finally tossed his book aside.

Then, he feels, he and Gretchen were united, in a way, by television.

“I turned on the Ed Sullivan show and later I found out Gretchen was watching it in California. In fact, she was laughing at Wayne and Schuster, a comedy act on the show, just before the baby was born. I was, too. So, in a way, despite the fact that the Sullivan show was released by tape on the Coast two hours later, we held hands across the country at the crucial moment.”

Actually, Dave was working when the baby was born and since his father-in-law didn’t want to bother him in the middle of a show, he waited three hours to phone him.

“It was like getting married,” he said later. “You know, you’re curious about what it’s going to be like. It takes only a couple of minutes to get married—so that you don’t feel any different—and then, the next morning, you wake up and discover your wife next to you. You say, ‘My gosh, this is forever!’ You’re not complaining,” he added hastily, “but it hits you that way . . . that it’s forever. I had the same feeling when Catherine was born, as though suddenly I had this tremendous responsibility to protect and care for someone else.

Plenty of best men

“You know, belonging to a trio is a little like being married, too,” he said wryly, tilting back his chair until his crew-cut brushed the wall behind him. “You know—with all the responsibilities and none of the advantages. Except for one,” he admitted. “All of us got married after we started singing professionally so there have always been plenty of best men on hand.

“But seriously,” he went on, “we spend so much time together as a trio, we have to be careful we don’t get on each other’s nerves—that could ruin our professional relationship.”

“So far, no problem,” Bob said, elaborately crossing his fingers. “We found the best way to stay friends is to lead separate lives as soon as we finish working. On the road, we always have separate rooms and we bend over backwards to make sure we don’t invade each other’s privacy. The same is true when we go home. Once we walk off that plane, we don’t see each other until it’s time to get back on.”

“Even though Bob and I grew up together in Hawaii,” Dave interrupted, “and we’ve known Nick since college, we have different friends, mostly people who don’t care whether the Kingston Trio lives or dies. When we finally get home, we’re absolutely incognito and incommunicado. We stay right around the house all the time, no night clubs and no parties,” he emphasized with a wave of his hand. “As far as I’m concerned, that time is just for Gretchen and the kids.” All three boys agree.

“One thing about being separated so much,” Dave added. “You have a lot of time to think about your marriage and you really understand how important it is.”

“It’s strange,” Bob said. “Sometimes it takes something pretty serious—like almost dying—to realize how much a person means to you. You know, Louise and I met in Hawaii and it was love at first sight . . . For me, at least. I spent the next six months convincing her—mostly by phone—to marry me, but I never knew how much I really cared until I thought I’d never see her again.”

So little time

It was the day before the wedding and the Trio was flying in from St. Louis for a one-night stand at Notre Dame University in South Bend. At that time, they were still using the chartered plane they had nicknamed The Tom Dooley because, Nick explained, the song “Tom Dooley,” their first big hit, was what got them off the ground in the first place.

They were somewhere over Michigan when it started to snow. Visibility was zero, their gas supply low, the plane was bobbing like a cork and they couldn’t get clearance to land at South Bend. Then the radio went out. The pilot had no choice but to drop down to about two hundred feet above the ground and try to follow the highway signs.

The Trio started to sing, not one of the folk songs that had made them so popular, but a hymn, “Nearer My God to Thee.”

They had gone through it twice when the pilot spotted a clear patch of land and headed in. The three of them looked out the window to see a snow-capped field and, holding their breath, watched as the pilot missed a haystack by a couple of feet, tipped a barbed wire fence and, by a miracle, made a perfect landing.

Still dazed, they crawled out of the plane, struggled through the fields to the road and managed to hitch a ride to South Bend. As they staggered up the steps of Notre Dame, a student stopped them.

“Look, you guys,” he called, “if you’re trying to buy tickets, they’re all sold out. Come back next year.”

Afterward, they laughed about it but it was a sobering experience. “All I could think about was Louise,” Bob said. “That’s when I really knew how much I loved her. It struck me how little time most people have to spend together, that even if you’re always together, if the husband doesn’t travel, still there’s so little time.”

“There’s no getting around it,” Nick added quietly. “It’s tough when you’re away from someone you love. I don’t think you ever can adjust to something like that, not really. At least I haven’t been able to. You may learn to accept it more, but you don’t feel any better about it ”

“You learn to make the most of the time you have together,” Dave said. “You know, when we’re on the road, in those lonely hotel rooms, I dream of the day when we’ll have a chance to live like ordinary married couples. But even then,” he added thoughtfully, “it’s just like Bob said. You never know it but there’s really only a little time. You have to make being together count. You can’t take those hours for granted.”

THE END

The Kingston Trio sings on Capitol Label. Hear them on CBS Radio, Mon. through Fri., 10:25 a.m., 12:55 p.m., 7:25 p.m., and Sun. at 5:55 p.m., 7:50 p.m. All times EDT.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1960