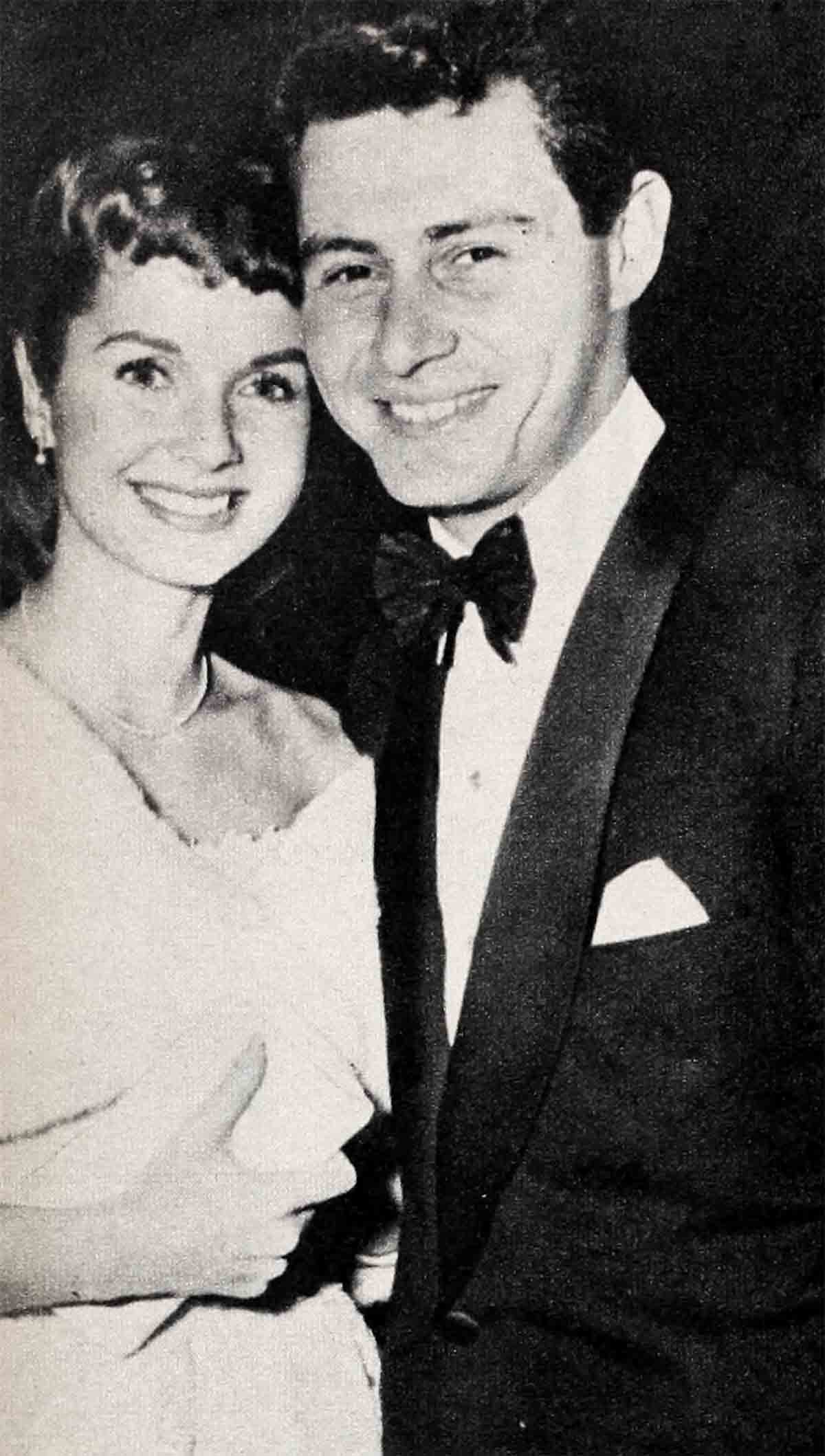

A Guy And His Dungaree Doll—Debbie Reynolds & Eddie Fisher

We want ordinary things,” says Debbie Reynolds Fisher, looking as pretty as ever but sounding mighty solemn. “After all, everyone wants about the same things out of marriage, and Eddie and I aren’t any different.” Maybe this is so, but during the first couple months of her “honeymoon,” Debbie woke up most mornings to find business conferences going on in her living room, kitchen—and sometimes where she was hoping to take a shower.

And Eddie adds, flashing his’ famous boyish smile but sounding as serious as a UN delegate, “We want just normal things. The things every other couple wants. Why should we be different?”

Eddie and Debbie are being normal in what should normally be their living room but at the moment looks like the inside of an oversized, crazy mixed-up cornpopper. There are two agency men in one corner—supposedly conferring but actually jabbing at each other with king-size pencils—while an independent woman with an agency-type pencil scribbles into a notebook as if she were keeping score at a basketball game, and an unidentified pink-faced man mulls over a crossword puzzle, crackling a pencil between his teeth. Then, too, a television set is on, displaying a quivering image, and two telephones are playing “Little Sir Echo” at full tilt. Two suspicious poodles and an anxious reporter with another nervous pencil, round out the scene. Everything and everyone is going at the same time. Suddenly, Eddie takes it all in with an appreciative grin and says, “Well, maybe it’s not so normal after all.”

The Fishers were married September 26, 1955 in upstate New York. They haven’t yet had time off for a real honeymoon. The day after their wedding they returned to New York. Then they went to a bottlers’ convention in Washington, D.C. Then back to New York. Next, to South Bend, Indiana. Back to New York. They flew to West Virginia. Back to New York. To Florida for another convention. Back to New York. To Philadelphia four times. Back to New York four times. Now count in Debbie’s sudden flight to California when her mother took ill, plus Eddie’s television shows, recording dates, conferences, rehearsals, promotion meetings, and so on. Add them all up and you have a faint idea of what it’s like to be on a hectic honeymoon. But in spite of all the work and traveling, the newlywed Fishers were making heroic efforts to carry on like average newlyweds.

When Debbie began cooking, Eddie put in his thumb, pulled out a tacos and said, “Vive!” They went shopping together and suddenly Debbie heard herself saying, like any other spouse, “But you don’t really need it, dear.” And like all other newlyweds they were adjusting and planning, making little compromises and getting organized.

“I think it’s the wife who should give in on an argument,” says Debbie. “I think it’s false pride to hold back and, if an apology is due, I like to beat Eddie to the punch. And I believe a wife should try, as much as possible, to adapt to the husband’s way of life.” Then she grins and says, “First thing I agreed to was to give in to Eddie and sleep late every morning as he does.”

Actually, it had worried her a little. On the West Coast, a working movie star goes to bed early and rises early. On the Atlantic side, a star singer goes to work after noon, goes to bed after midnight and wakes around eleven. Debbie, knowing about this, recalls, “It bothered me a little. I thought after we married I’d be wide awake about six or seven and then have to wait around until noon for Eddie to get up and say hello.”

Debbie discovered it was easy to get up late. All she had to do was stay up late. She fell in with the new system so well that Eddie notes, “This morning I gave her an extra hour, and the day before it was at least an hour and a half.”

Eddie is an eight-hour man and Debbie likes ten hours a night.

“Living on the West Coast, we don’t have the same problem,” Eddie says. “There my day starts much earlier—about eight. Of course, Debbie has even earlier hours, but I’ll tell you” he says and smiles, “if she leaves for the studio at five-thirty or six, you know who’s going to be at the door to kiss her goodbye—the poodles. It’s not that my spirit isn’t willing. It’s just that the body won’t cooperate that early in the morning.”

So far, adjusting to minor problems has sometimes been a matter of mere physical agility. Eddie uses his hi-fidelity phonograph a good bit. Debbie likes music, too, but he likes the volume up so loud that you can hear the second trumpeter lighting up a cigarette. Eddie may say, “Listen to this, dear. I want to play something for you.” So he puts on the record but when he turns around Debbie has disappeared. Usually, she has just gone to the far side of the room, her back braced to the wall to resist the musical storm.

Getting together on other minor things also requires a little bit of understanding. Both Eddie and Debbie admit they are impractical, but in different ways.

“Take shopping,” Debbie says. “Everyone likes to shop—but me, I’m a bargain hunter. Unfortunately, sometimes I get carried away and come home with bargains I have no use for and, in the end, just give them away. Now Eddie’s different. He gets to shop only two or three times a year, and he goes from department to department to buy everything.”

Debbie was with Eddie when he took a fancy to a new sweater.

“You’ve got a blue one at home,” she pointed out. “The exact shade of blue as this one.”

“But I like this one better,” Eddie said.

“But if you buy this,” Debbie asked. “what will you do with the other?”

Telling about it, Debbie suddenly interrupts herself and says, “You know, Eddie deserved it. He’s very fond of good clothes. And when you stop to remember there were periods in his life when he had to do a lot of skimping, you can understand why he deserves a few extra luxuries now.”

Now you might conclude that Debbie is the down-to-earth, practical, cautious one and that Eddie is the kind who always needs a string attached to his kite. But people don’t classify that easy. Take driving, for example. When Eddie is behind the wheel, he is a moderate, cautious driver. If you had two dozen eggs in a basket, Eddie’s the boy you’d ask to drive them home for you. But when Debbie’s driving, she believes the shortest distance between two points is the maximum legal speed.

Or look at the way they each make decisions.

“If I have to decide on something,” Debbie says, “I do it quickly. I’ve made most of my own decisions in my career. Sometimes it’s a question of choosing between making one of two pictures. I’ll a in one hour or, at the longest, in a day.”

Eddie, on the other hand, likes to analyze and think the situation out. “I’ll take a week,” he says, “or longer if I have to.”

They’re getting together on sports. Eddie is athletically inclined and Debbie was majoring in physical culture before she was drafted into pictures.

“She taught me to water ski a year ago,” Eddie says, “and I’m real crazy about it.” He recently bought Debbie a set of golf clubs, but left the teaching to a pro. “Look, I’m not that good to be teaching anyone, but you should see her swing. She’s a natural.”

Debbie, too, is a great dancer. While she finds Eddie so-so in the ballroom category, future plans call for more intensive training at home, which in itself does not sound unpleasant. Together, they enjoy sports, entertaining and movies. In the case of movie-going, however, their bachelor pasts are catching up with them.

“We usually agree on the picture we want to see,” Eddie says, “but there was one movie Debbie wanted to see which I’d already seen. So we compromised—I saw it twice.” Eddie grins and takes the sting out of the joke by adding, “Actually, Debbie’s seen a couple twice for my sake, too.”

In some ways, the major adjustments in the first couple months of marriage were Debbie’s to make. They lived on the East Coast in a manner to which the groom was accustomed—out of hotels and suitcases as Eddie had been doing for years. For Debbie it meant making new friends with Eddie’s old friends, entertaining his business associates and having his family in for home cooking. She made the adjustments smoothly, intelligently and with good humor. She even changed her style of dressing with no ill effects.

“I loaded up with those ‘late-for-a-date’ dresses,” she says. “I’ve got a half-dozen of them.”

Usually Debbie likes sport clothes, but they take a few minutes longer to get into.

“These are just sacks with a hood,” she says. “You can get them on in ten seconds flat. Pull them over your shoulders and you’re set. All you need is a belt, a body and a head.”

Punctuality is one. problem the Fishers have not been able to solve so far. Both admit they are often late for dates, but this has little to do with weakness of character.

“It’s like this,” explains Debbie. “You’re told you have to do and see so many people and things on a certain day, and so you say, ‘All right.’ Then appointments are made right down the line and, in planning, everything is figured on taking ten or fifteen minutes less than it should or does. Well, you run five minutes over on the first date and you’re fifteen minutes late by the time you finish the second, and you’re going from one side of town to the other, fighting traffic. By noon time, you’re so far behind that you have to cancel out a personal luncheon date to get back on schedule, but in the afternoon the same thing happens all over again.”

Debbie doesn’t pretend she has time for household chores as well as picture work—but, nevertheless, she started off by proving to Eddie, his friends and his mother that she wasn’t a total loss around the kitchen.

“I understand there are two schools of thought on Debbie’s cooking,” Eddie says. “One side says that her talents are limited to opening up a box of Girl Scout cookies, and the other says that she can cook enchilladas a hundred different ways. Actually, she is a good cook, but a new one.”

Having lived for a while in the heart of Texas, Debbie is partial to cornbread, black-eyed peas and Mexican dishes. She has also learned to make some of Eddie’s favorites—such as lima beans the way his mother used to make them. She has taken instruction in cheese blintzes, which are comparable to Crepes Suzettes only better. To make a blintz you first must prepare a golden sheet of pastry as thin as tissue paper. This is then folded around a mixture of cream, cottage cheese and a few other ingredients, then baked. It’s not easy and, Debbie admits, “I got a lesson from one of the best chefs in Manhattan.”

Dinner is the only meal she ever tries to prepare. They eat lunch out and seldom bother about breakfast.

To date, there have been no kicks about the chow and Eddie, with his GI experience, has proved to be an expert at “not volunteering” for kp duty. It’s not a trick or a technique but, actually, a fine art when properly practiced. For example, if you’re wearing a brown suit, you stretch out on a brown sofa and put a brown pillow over your face and, by adjusting properly, you practically disappear.

“Oh, he would help, I’m sure,” Debbie says optimistically. “I remember when he used to come to our house for dinner he would help Mother with the dishes.

That was prior to the wedding.

“I think maybe Eddie could make a salad,” she says.

“A salad?” says Eddie.

“You know, a simple salad. Chop up some lettuce and a cucumber.”

“Cucumber,” he says. “What’s a cucumber?”

This coming from a young man who once huckstered vegetables is an excellent example of practical brainwashing.

Joking aside, neither takes their marriage and future lightly. Hectic the life may and young are the newlyweds, but disorganized or impetuous, they are not. It was a surprise marriage to many, but not to Eddie and Debbie. When she came East to marry, she came prepared to stay two months and, when she returned, Eddie accompanied her, prepared to stay in Hollywood and do his telecasts there until he could return to New York with Debbie. It may have sounded sudden but it couldn’t have been planned better by a military genius. Even their Christmas cards (a picture of Eddie and Debbie and their three dogs) was chosen long before they knew where they would be dining on Thanksgiving. And when they got to Hollywood there was a house waiting for them. Debbie had chosen the house and signed a one-year lease before she “eloped” to New York.

About their home, Debbie says, “We’d still like to build our own as we planned. We’d like to have acreage in Beverly Hills or in the San Fernando Valley, but it’s not easy to find what you want and it’s very expensive. When we do build, we know exactly what we want. It will be in the style of an English country home and it will be furnished with a mixture of contemporary furniture and English antiques.”

She, alone, chose their present home. It was originally built for Norma Shearer. It’s fairly romantic but not built in hotel proportions. It has only two bedrooms. It is high up, overlooking the ocean and, on a humid day, you can almost feel the spray of the surf. The house itself is ranch style, furnished mostly with Early American furniture, and is set on four acres of natural shrubbery, which means they will have none of the nuisance of formal gardening.

“They are putting in a natural, primitive-type pool so we’ll have the fun of that,” Debbie says. “Eddie and I are both sun-worshippers and love the water.”

Whether or not the home is practical for raising children is not important, since they have only a year’s lease. Neither one lacks enthusiasm for kids and Eddie holds a practical viewpoint: “Kids aren’t something you plan or postpone like putting up a house. The right time is anytime.”

Debbie was once quoted as saying she wanted six children.

“I like what Arthur Godfrey said about that,” Eddie notes. “He said that no woman can say she’s going to have six children until she’s had five.”

Debbie doesn’t even remember saying six. “How many children? When?” she echoes. “Well, it’s not in our hands.”

But she has thought about names and, when the time comes, if their first is a boy, she would like to call him Kevin; if it’s a girl, Kathy.

There are other things they think about for the future besides children and house, for both of them are serious careerists. Debbie, who raced back to work on a new picture, “The Catered Affair,” has very definite ideas about her career.

“I like comedy and I like slapstick. I’ve always been a great admirer of Cary Grant and I’ve seen all of the old Carol Lombard pictures. Sometime soon I’d like to do sophisticated comedy.”

And next summer, Eddie is likely to spend his vacation from television making his first movie. If he doesn’t, he will make good on a promise to take Debbie to Europe. But no matter what they do you can bet on one thing—you will seldom find Eddie and Debbie separated. It’s happened just twice since the wedding. The first time Debbie was just “lost” from Eddie.

“Eddie had to go to his tailor’s,” Debbie recalls, “and for me a fitting always takes two or two and a half hours, so I expected the same held true for a man.”

So about an hour and a half after they’d separated, she went to the tailor’s to meet him. She was told that he had left twenty or thirty minutes before.

“Suddenly I felt awful. Awful lonely.”

She left the tailor, then paused out on the street. She was trying to decide whether Eddie had gone north or south, east or west, when a strange man walked up to her and said, “You looking for your husband? He went that way.”

So she started north and about two blocks up another man stopped her and said, “You looking for Eddie? He went that way.”

She took the turn and as she passed a delicatessen, a clerk tapped on the window and beckoned her in. “Your husband was here and bought a roast chicken. When he left here, he crossed the street.”

She crossed the street and found herself near the grocery store they used. She was told that Eddie had been there to shop and with that she began navigating herself, following the shortest route back to their suite. There, in the kitchen, was Eddie with the groceries and a roast chicken.

“Well,” he said, “I guess we missed each other.”

They were really separated only once, shortly after their wedding. While Debbie ‘was still in New York her mother took ill. Debbie flew to California, spent a full day there and was back with Eddie on the third day.

“I should have stayed longer with Mother, although thank goodness it was nothing serious, but I knew Eddie needed me and I had to rush back. You know what they say about absence making the heart grow fonder. That’s just part of it. It hurts awful, too.”

Maybe the kind of life they have to lead isn’t normal because of the demands of their careers, but Eddie and Debbie as persons are. In childhood, both learned to appreciate and love family and home. So they have an understanding of values. They know that the one thing their happiness depends on is being together. And as Eddie says and as Debbie says, that’s all that any normal couple wants.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1956

No Comments