“I will be your son!”—Evelyn Keyes

There’s a new man in the life of Evelyn Keyes. Drop in one of these afternoons, and you’re likely to find him in the pool. Ask him his name, and he’s likely to tell you: “Pablo Albarran Huston Evelyn Keyes.”

A Mexican boy takes his mother’s name along with his father’s, but Pablo’s been in the States some two months now, and he knows the difference. This is one of his jokes. He dies laughing over it. Look beyond the joke, and you’ll find it’s also a statement of fact very pleasant to the soul of Pablo—the fact that he now has a mother and father.

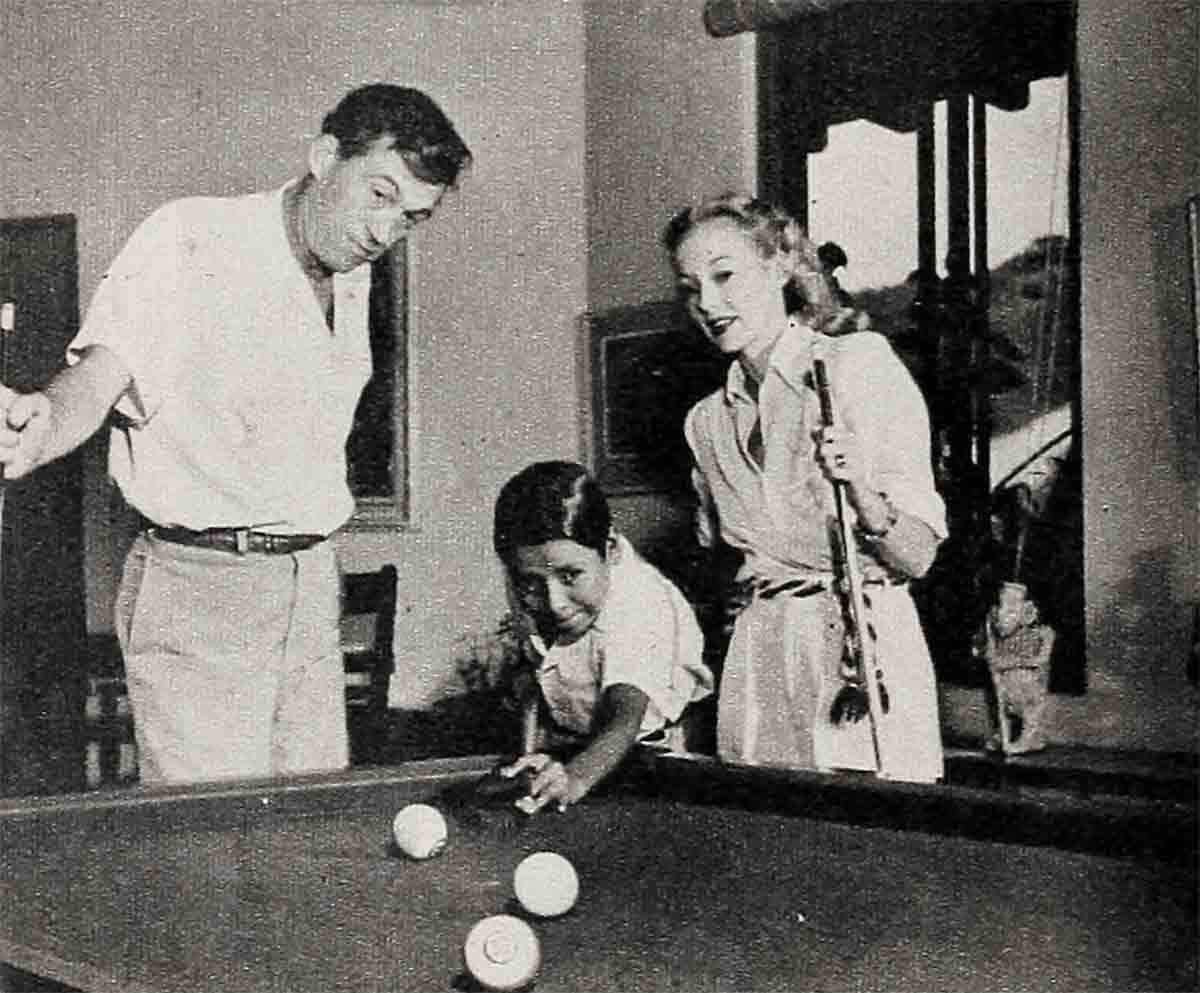

He calls them Mommy and Poppy, and divides his attentions half and half between them. Having kissed Evelyn, he’ll rush over to do the same by John, and vice versa. Walter Huston is Grandfather. Grandfather’s teaching him baseball, and for hours on end they’ll stand there, so many feet apart, the small boy and the tall silver-haired man, pitching the ball back and forth.

Language still forms a barrier between Pablo and his parents. But they do well enough, considering that Buenas tardes was all the Spanish John and Evelyn knew when they got to Mexico, and all the English Pablo knew was nothing. They use a lot of pantomime. Pablo pantomimes, anyway, whatever the language. Un momento, por favore, or “When moment, eef you please—” his forefinger cuts the same vivid little arc, and either way you stop and look and listen.

Mornings, he studies English with a tutor. Evenings, he pops new words at appropriate moments. For instance, the dessert comes on. “Ah, wahnderrful,” says Pablo, pulling his mouth into gravity while his eyes dance. Sometimes he gets mixed up. Stretching himself on the floor, he’ll announce: “Me crrazy!” They have to resort to the dictionary to clear up the radical difference between crazy and lazy.

But it won’t be long now. He’s already talking in sentences: “I go frand’s house.” His teacher reports that, once the language is licked, he’ll be able to enter school in his own age-class.

hidden treasure . . .

So far as Evelyn’s concerned, you can call Pablo the Treasure of the Sierra Madre. The Hustons discovered him in Michoacan, where John was making the picture of the same name with his father and Humphrey Bogart. Evelyn and Lauren Bacall went along to be with their husbands. They stayed at San José de Purua, a health resort set in the midst of gorgeous tropical country. The girls found loafing more attractive than the hot location sets, but every once in a while they’d say, “Coax us,” and go along with their working men. On one such occasion, in the nearby village of Jungapeo, Pablo made his first appearance.

This was dramatized by a burro, who got bored sticking around and wandered off on business of his own. When they tried to nab him, he went flying up the mountainside, with what looked like a pint-sized Mercury in pursuit—up and up till boy and beast seemed to vanish. Ten minutes later they were back, the burro no more doleful than usual, the boy beaming. John hired him on the spot as general handyman.

This seemed delightful to Pablo, but also natural. Half the village was working for the Americans, why not Pablo? In a community where four-year-olds look after babies or bring in a dozen donkeys, and no nonsense about it; you’re a man at twelve.

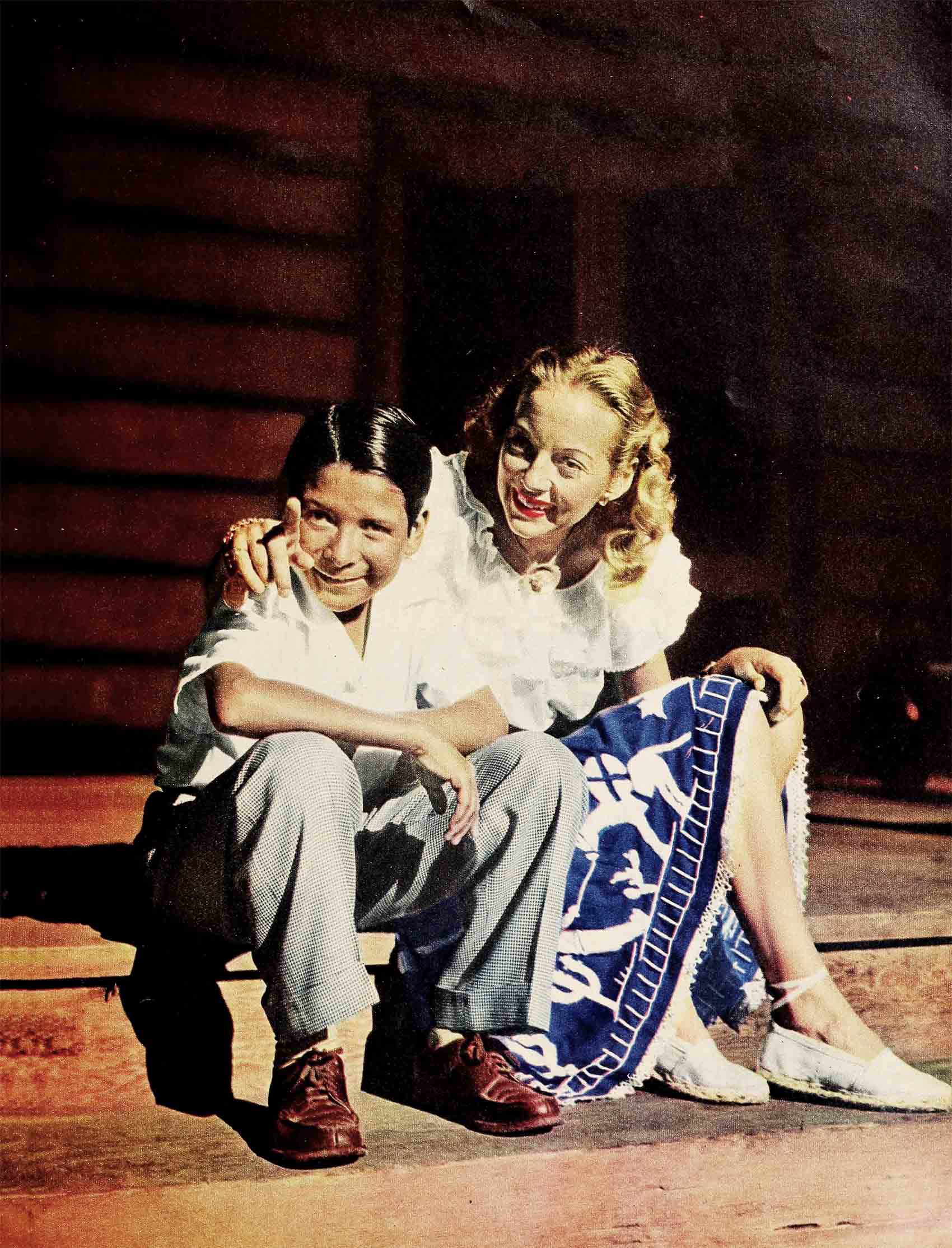

Everyone fell for Pablo. His laughter was so infectious, his eyes so alive with interest in all that went on, and yet, he had a poise and breeding that never allowed him to push himself. Once he’d brought your chair or your cool drink, he’d slip back to the sidelines.

One Sunday, the village gave a fiesta for the Americans—with a barbecue sandwiched between an afternoon rodeo and dancing at night. Pablo was there. Evelyn’s eyes kept following him. “John, I’ve got to find out about that child—”

John went for an interpreter. They found out among other things that Pablo was an orphan. He didn’t put it that way. In Spanish, it was the phrase a bachelor might use, or an old man who’d outlived his family. “I walk alone,” said Pablo. There was no self-pity in it, only simplicity and a touch of honest pride.

“Twelve,” observed Evelyn later, “and he walks alone.” She and John had talked of adopting children. “If we really want to, there’s the kid to adopt—”

“I wish we could,” said John, and there they dropped it, not being the kind to lament over impossibilities.

Next thing, Evelyn’s back in Hollywood to start The Mating of Millie for Columbia, leaving the others at work in Michoacan. Then comes word from John that the picture’s finished, and they’ve started home. Then a call from Mexico City.

“I’m going to be two days late—”

“Oh, John! It’s been two weeks already—”

“I know, but this is very important—”

“Can’t you tell me?”

“No, it’s a big surprise—”

Two days later, Evelyn met the plane. She saw John first, he was bigger. Beside him walked a small figure, face half-hidden under a large sombrero. The sombrero was John’s. He’d clapped it on Pablo’s head, partly in fun, partly to get rid of it. For a moment Evelyn stared unbelieving. Then the hat and the legs below it came catapulting toward her. What did she do? What would any mother do?

“It grabbed him,” says Evelyn, “and I gobbled him up—”

As it turned out, the impossible had proved quite simple.

One rainy night after she’d left, John sat talking to the Mexican censor on the picture, a man of heart and learning, head of the Michoacan Museum. Sunk in a chair on the other side of the room, Pablo devoured B. Traven’s Treasure of the Sierra Madre in Spanish.

“Be nice to adopt a kid like that,” said John.

the way opens . . .

The censor’s eyes went to the boy and back. “Michoacan,” he said, “is the one Mexican state where an orphan’s guardianship reverts to the local government. If you mean what you say, it might be arranged.”

“Let’s arrange it then.”

They called Pablo over. “Here is a matter which concerns you,” the censor explained. “This gentleman and his wife wish to take you as their child. It means leaving Jungapeo and Mexico. It means going to the States, and a whole new kind of life. It is something for you to consider and decide—”

Pablo considered. Never having stepped beyond the confines of his small village, the States meant little to him. The lady and gentleman seemed to mean a good deal.

“These people are willing to be my parents?” Obviously, walking alone was fine if you had to. Parents, on the other hand, were a gift from above. “I will be their son?”

“You will be their son.”

The big eyes looked steadily into John’s for a moment. “Yes,” said Pablo. “I should like that very much.”

Everyone liked it. Cutting red tape, the local authorities got their part done in two days. The censor flew to Mexico City to help with details. Before John left, Pablo was ward of the Hustons by Mexican law.

If all this seems sudden, if you’re wondering how John could be sure that Evelyn really wanted the boy, it’s because you don’t know the Hustons. They live spontaneously. Three weeks after their first meeting, they were married. Indecision irks them; they take what seems good in life where they find it. When Evelyn said, “There’s the kid to adopt,” John knew she wasn’t just tossing words around. ‘Both recognize quality when they see it—

In which connection, Evelyn tells a story that has nothing, yet everything, to do with Pablo.

One day, she went location-hunting with John. Driving ahead of the rest, they stopped at a place whose magnificent trees shaded an adobe hut, ideal for the scene John had in mind. Out stepped an old man in serape and sombrero, with the face of a patriarch.

“Buenas tardes,” they chorused.

“Buenas tardes,” he answered, and stood smiling down at them, since it was clear they had no more Spanish to offer. The others came up. It was explained to the old man that these strangers wished to photograph his land for its beauty, and would be glad to pay for the privilege. He mounted his doorstep, and, with a courteous gesture that took them all in, made a little speech.

“I am poor, therefore money is important to me. But other things are more important. I see my land with eyes different from yours. That you who have traveled so widely should find it beautiful, does me great honor. The land is at your service.”

For graciousness and dignity you couldn’t beat it.

“That man was no kin of Pablo’s,” Evelyn says, “but he might have been. They come of the same stock. Pablo was the son of people like that.”

On the way home, Pablo’s poise was shaken only once. Naturally, he was all eyes and ears and attention. The plane, the crowds, the shower-bath he’d have turned on and off all day if John hadn’t pulled him out, the shoes that cost pesos! These were all wonders, but understandable. He kept his composure. The only thing that threw him was the hotel elevator.

They crowd into this small little room with many others. A strange performance. But it seems all right with his father, so it’s all right with him. The door closes—and opens on a whole new change of scenery. Also peculiar. They go to their room, wash up, and come out again. Leading Pablo to the stairhead, John points down. “Oh!” squeals Pablo, reeling back with a grand gesture as the truth hits him. In that small little room, crowed with many people, they’ve been borne to this great height. When the small little room returns, he takes an enormous stride over the crack and squats promptly in a corner. Father or no father, this is something he doesn’t trust.

At no other point was his equilibrium upset. When they took him home from the airport, there was no tearing around to touch this or admire that. His feeling seemed to be: “This is your house, you’ve brought me here. When you want me to see it, you’ll show it to me.” That first night at dinner, faced with an array of silver, he watched without embarrassment, to see what John and Evelyn would do and followed suit. This was how they ate in America. Being the son of Americans, he would now eat this way.

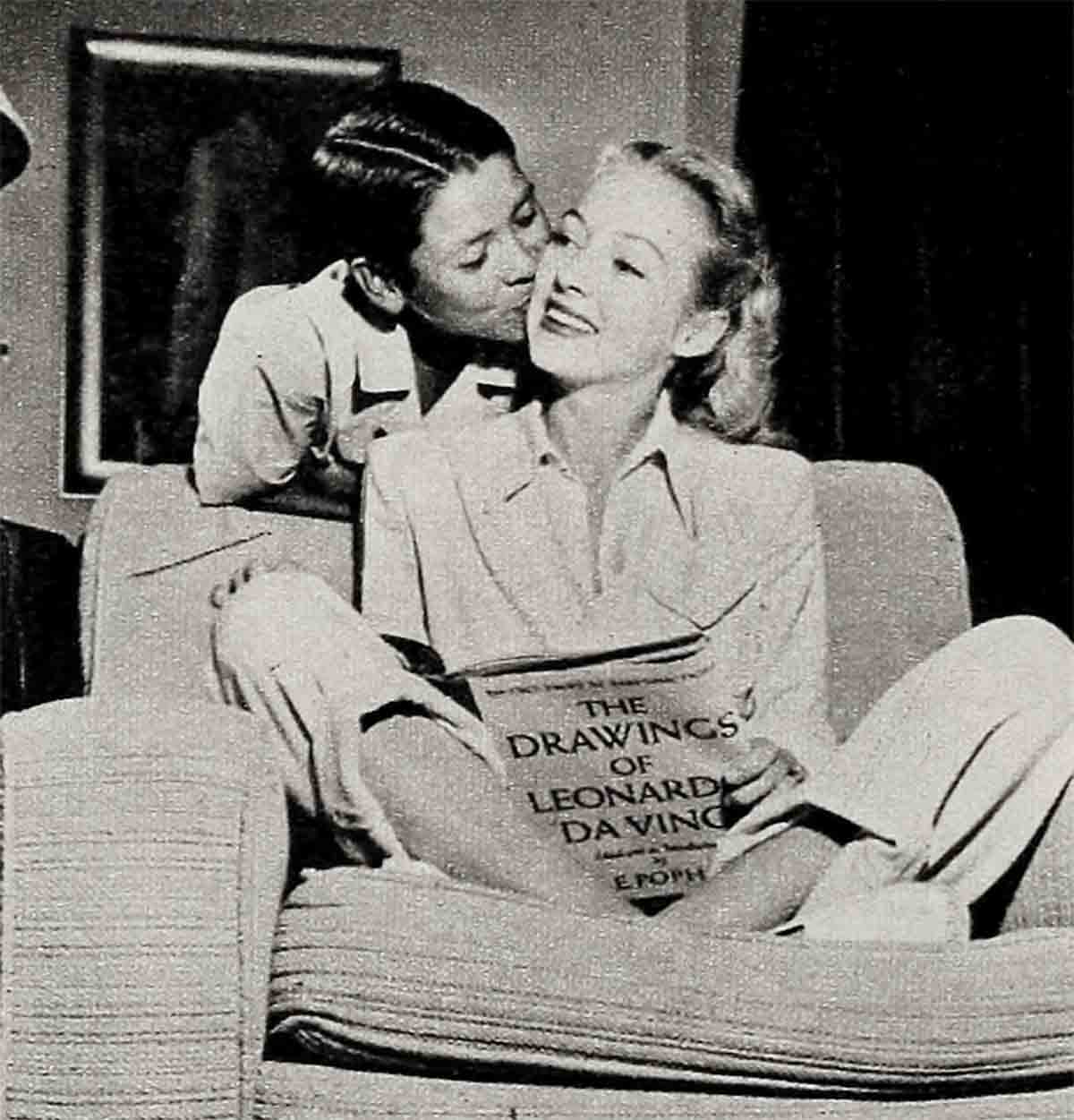

It was a rule he seemed to adopt from the start. The week he arrived, Evelyn couldn’t bear him out of her sight, and took him along to the studio where seven different kids were testing with her for the part of Tommy. At the end of the scene, each kid had to plant kisses all over her face. Having watched it seven times, Pablo must have reached the conclusion that this was how children kissed mothers in America. He’s been kissing Evelyn that way ever since. She hopes he’ll never find out that American 12-year-olds consider it sissy to kiss their mothers at all.

To Pablo, John and Evelyn are as truly his parents as if they’d been his parents from his birth. Their home, their friends are his. It’s something beautiful that’s happened to him, he’s thankful for it, he loves them dearly, as they do him, and that’s that. They’re all relaxed about it. If you’re bent on rubbing the Hustons the wrong way, call them benefactors. They’ll tell you the benefaction’s on the other foot. They know what the coming of Pablo has meant to them. Whether they’ve done right by him remains to be seen.

“How can you tell?” demands Evelyn. “He was happy down there—the best adjusted human I’ve ever met. It must have been pretty exciting Saturday nights, hanging around the cantinas, with the dancing and music and even the brawls, and no mother to say don’t go. Maybe life’s dull for him here. So he’s got a bed, and he’s supposed to be in it by nine o’clock. Where’s the fun in that? If John said, ‘Come on, let’s sleep on the lawn tonight, or over there on the mountain across the way,’ I’m sure that would make perfect, good sense to Pablo. He’s a child of nature. We Americans are full of complexes and self-consciousness. How do I know we’ve done him any favor?”

Meantime, Pablo’s not kicking. Maybe the comforts don’t matter, but the love does, and being part of a family. While Mommy and Poppy work, he keeps his end up by tending the lawn after lunch. He still finds it diverting that what Mommy and Poppy do should be called work. To him, the studio is a large playground. People sit around. Then they walk into a make-believe room and chatter. That’s work? Work is with muscles and with callouses on your hands. Meantime, he does enjoy the few movies he’s seen. These he attends with three friends. Manuel, who speaks Spanish, acts as interpreter. The Hustons have it in mind to adopt a brother for Pablo—an American near his own age.

“I envy him,” sighs Evelyn, “growing up with Pablo.”

Toward Mommy, Pablo assumes certain masculine responsibilities. Like making her rest when she’s tired. Or getting up to see her off when she has an early call. It’s also his job to pass on her clothes. She’ll be dressing to go out, with Pablo watching as she adds the finishing touches.

“Vairy good,” he’ll comment on a new hairdo or dress, and sometimes, “No—no good.” His vocabulary doesn’t run to explaining why it’s no good, but the judgment’s always made with serene finality.

his mother’s keeper . . .

About smoking, he hasn’t quite made up his mind. Today he’ll let it go, tomorrow he’ll take issue with it. As Mommy picks up a cigarette, she’ll find the finger wagging to and fro. “Okay for Poppy, no good for Mommy.”

“You’re perfectly right,” she’ll agree, and drop it back in the box.

This pleases him no end. On the other hand, he’d do as much for her. His singleminded idea is to give them pleasure. For instance, he draws, and very well, too. Each night when John came home, Pablo would have a drawing to show him. At first, to encourage him, John’s praise was unreserved. Then he grew critical, pointed out flaws. Next night, no drawing. Poppy had the devil’s own time, explaining that criticism wasn’t active loathing.

Within these few weeks, Pablo’s grown to be more of a kid. Like any kid, he loves to play jokes. Late one morning, Evelyn found him in bed.

“What goes on here? You should have been up long ago—” She pulled off the covers, under which lay Pablo, fully dressed. This he considered the rib of the ages.

Like any kid, he hates to go to bed. “Jost leetle beet more,” he pleads. “Jost wahn more pool.” And like any kid, he can be a pest. This doesn’t bother his folks. They enjoy seeing the years drop off. One day he was being a pest as they sat round the swimming-pool, teasing, monopolizing the conversation.

“That kid needs squelching,” said John, like any father. He picked his son up, hauled him struggling to the end of the diving-board, and dumped him in. Though he swims well, Pablo had never jumped. Now he clambered out and, without a word to anyone, ran up the diving-board and jumped, himself.

Then his face appeared at the pool’s edge, radiant with the grin which had first enchanted them both.

“Good boy now?” inquired Pablo, who no longer walks alone.

THE END

—BY ABIGAIL PUTNAM

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1947