Which One Is Lying?

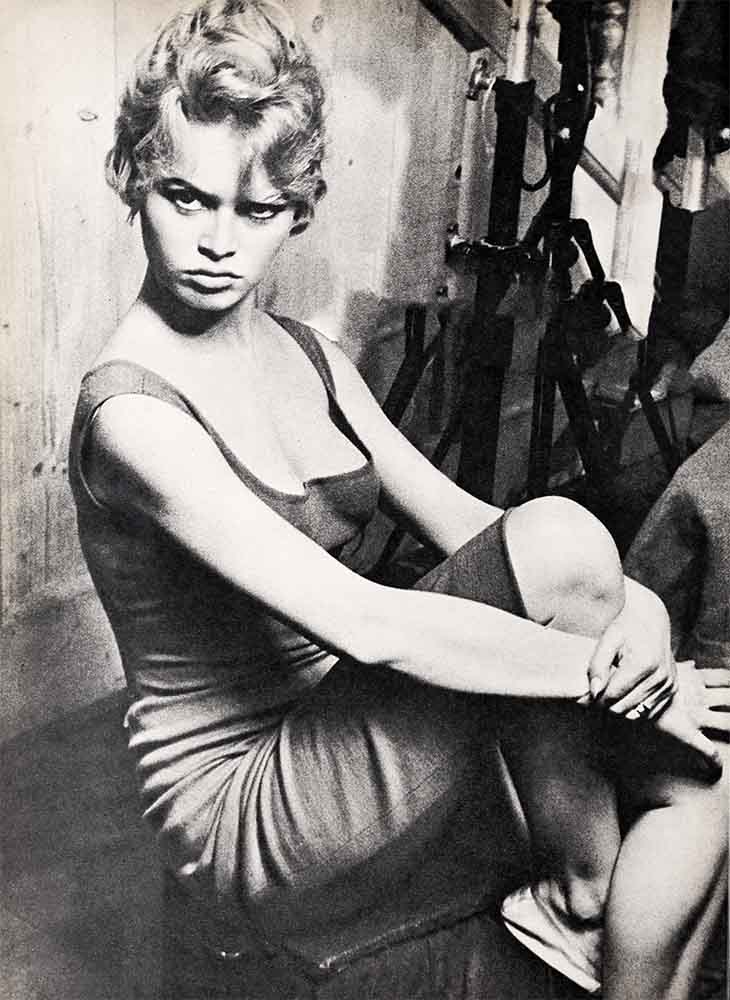

In the darkness of the theater she dominates the screen. She stands tall and slender, with long legs and long arms, bosom thrust forward. The full seductive body of a woman. Yet her face is something else again. The features of a petulant child. Her smoky, straw-colored hair looks like she didn’t have time to comb it and just ran her fingers through it, which is what she usually does. Her big, long-lashed, hazel eyes gaze out in a sullen stare. Her mouth is large, with prominent teeth and childlike, pouting lower lip.

Now she turns and walks slowly across the screen. Not the wiggling walk of the temptress nor the slinky sway of the siren. A natural movement, yet more lascivious and seductive than the more exaggerated wiggle and sway of the other sex queens.

To the men in the audience, Brigitte Bardot’s body and walk say, “Come here,” and yet there is something innocent about her face which says, “Don’t touch.”

These then are the two Bardots, the petulant child and the seductive woman, each speaking with a different voice. Yet which one is lying? And which is the true voice? Other voices—of the men who have known her best—answer quickly, each sure his is the right answer.

AUDIO BOOK

The sad, rejecting voice of the former husband, Roger Vadim: “No, I will not remarry her. Happiness is impossible with her unless we went to live in Labrador on reindeer meat and dried fish. For her, now, being a celebrity has become Hell. She cannot build or keep anything. Everything that is hers is public. She has become the property of the crowd.”

The adoring, jealous voice of the lover, Jean-Louis Trintignant: “She is a lost child. She has everything to make her happy and yet she is unhappy. I think I can lead her to happiness. It is not the star that people see on the screen that I love. I cannot bear it, when I’m embracing her, to think of all of the leering millions who would like to be in my place.”

The gently chiding voice of the father, Louis Bardot, whose poem—one of many he has written to her since she was born—won a top award in France: “Pretty, light shepherdess, I think you exaggerate. Lover, husband, children are not enough for you.”

The admiring yet ironic voice of the famous producer, Raoul Levy: “Although she has become a sort of universal sex symbol, that is not really her at all. She is a good girl—always loyal to the man she is going with at the moment! Why, she has gone with the same fellow for at least ten months!”

The brutally direct and honest voice of Bardot herself: “I want there to be no hypocrisy, no nonsense about love. . . . What do I prefer in a man? Mouth, teeth and sincerity.”

No hypocrisy. Roger Vadim, her discoverer, her first husband and still her good friend says: “She cannot lie.”

Brigitte herself echoes this. “Oh, make sure you understand that I don’t act,” she says. “What you see on screen is me. What I do in the films is really me in real life. . . . I am sexy but at the same time I am anti-sexy. I am a woman but at the same time I am a little girl. I am always two persons at the same time.”

Girl? Woman? Girl-woman? Can we accept Brigitte’s own confession as true? Why would any woman want to remain a little girl? What does being a little girl mean to Brigitte Bardot?

A little girl . . . frizzy hair; large teeth; thick, puffy lips; dented pug nose; long, gangling, awkward figure. “I’m ugly,” she’d tell herself as she squinted at herself through her thick eyeglasses in the mirror. “Ugly!”

Mama was beautiful and elegant. Mama owned a dress shop and knew all about fashions and clothes and beauty.

She could never be like the glamorous ladies in the shop. She would never be like Mama.

Not that Mama didn’t try to make her beautiful; she did. But it was hopeless. Mama just refused to see her for what she was. Ugly. Hopeless.

Years later, she still recalls this period with pain. “It is true I am never really well groomed,” she says. “When I was a young girl this made me be the despair of my mother. She used to take away my dessert and forbid me to go out.”

Sometimes, she would be sent to her room. Yet somehow that punishment wasn’t so bad. Brigitte’s room became a place where she could pretend. There was one doll there she called “Mama.” Mama never went to work. Mama didn’t hag her about her clothes or her looks. Mama took her to dancing school, watched her as she practiced her ballet steps and applauded her as she whirled around the school stage in a white, fluffy dance costume.

She named another doll “Papa.” Papa begged her to go outside and play with the other children. Papa told her all about boys and encouraged her to bring boys over to the house. Papa didn’t mind at all when she sang and danced and made noise. She could talk to Papa. He was her friend.

She had some toy soldiers she pretended were “boys.” In her games she didn’t know what to do with them. When she put make-believe words in their mouths, what they said was stilted and peculiar. Most of the time she didn’t make them talk at all. Who knew what boys said?

Her fuzzy bears were “girls.” They also didn’t do much talking. What do girls say to each other? What do girls say to boys? Most of the time, the bears were lined up opposite the soldiers and they just stared at each other in silence.

When she was thirteen, her body was still scrawny and stringy. Her mother made her wear sailor hats with wide brims and prim little collars, and she was miserable. The only things she really liked were her ballet classes—she felt free, somehow, whirling and gliding around the stage and her own room. where she could pretend that Mama and Papa loved her like parents loved children in books, and she could try to figure out what the soldier-boys might say to the bear-girls and what the bear-girls might say back.

Suddenly, she was fourteen. and her mirror showed her something was wrong. Her hips and legs were pudgy and her chest was round. She was confused. She was ashamed.

Then something amazing happened. One of her mother’s friends saw her in the shop and asked permission to have her model some clothes. And her mother, proud that at last she might learn to wear fashionable dresses, actually said “Yes.”

She herself wanted to say “No.” She was ugly. She was fat. She’d make lovely dresses look horrible. Besides, she’d meet soldiers—no, that wasn’t right, men, and she wouldn’t know what to say.

The night before her first modeling assignment she chose one toy soldier and called him “the man.” Then she selected one bear and said, “You’re me—Brigitte.” She tried to imagine what the man would say but she couldn’t think of any words. Then she attempted to put words into Brigitte’s mouth, but nothing came out.

She needn’t have worried. Mama was with her the next day and on all the other days that followed during the next two years, when she modeled dresses and posed for photographers . . . and Mama spoke for her.

Mama also did the speaking for her when Marc Allegret, the movie director, asked her to take a screen test. Mama was so busy talking, in fact, that she failed to notice the way an assistant director, Roger Vadim, was looking at her fifteen-year-old daughter. Mama was so intent in objecting to Allegret’s suggestion that her daughter change into a form-revealing bathing suit that she didn’t see how Roger stared at Brigitte and how the girl blushed.

Many times in the future Brigitte was to recall this day. “I thought he was like a young god,” she said. “I hardly dared look at him. I had been brought up under the watchful eyes of my parents and my governess, and I was scared whenever he looked at me. And yet, inside me, something was happening.

“I was afraid of falling in love with him and yet dared not hope that he could love me with my plain-jane face. But after we met in the studios a few times, he phoned me and asked me to dinner. I went, and I stayed with him till six in the morning.”

Mama was appalled. Papa was horrified. They didn’t know she’d stayed out till six in the morning (neither of her parents had heard as she sneaked up to her room). But they did know he was six years older than she and a member of the wild, movie-making crowd. When she said she was in love with Roger and wanted to marry him, Papa thundered, “No, you must never see him again.”

That night Mama and Papa and Bri-Bri went out for a while. When they returned, Brigitte was lying on the kitchen floor, gas jets of the stove open and windows closed. Papa Bardot picked her up and carried her into another room. At last she regained consciousness.

Yes, she could see Vadim whenever she wanted to, he promised. Yes, he could move into their apartment with her and share her room. Anything, anything at all, as long as they didn’t get married until she was eighteen.

So Roger found a place with Brigitte among the dolls and bears and soldiers. Years later, Mama and Papa Bardot said piously, “We’re almost certain nothing immoral occurred.” So for two years, at least, everything was acceptable on the surface. Vadim was a “friend of the family” and a “paying guest” in the Bardot household.

On September 28, 1952, Brigitte became eighteen years old. Three months later she and Roger were married.

The girl who never had a childhood was suddenly a woman. On the day of her marriage Roger whispered to her, “One day I will make you, Brigitte Bardot, the unattainable dream of every married man.”

Almost overnight she had left the safe, secure world of her own room and was plunged into the wild, difficult world of womanhood. She still didn’t know how a fuzzy bear talked to a toy soldier, and Roger didn’t help her much. Like Mama, he talked at her and through her but not to her. He treated her as if she had the body of a woman and the mind of an adolescent, and this was the image he taught her to project on the screen.

It wasn’t hard really. She didn’t know how to act with other people. She’d never had any experience. So she went where Roger wanted her to go, and did what Roger told her to do and said what Roger directed her to say. And she became famous!

Mama had once objected to her taking a screen test in a bathing suit; now she gave press interviews in the nude and shocked even the French censors with her ail-revealing undressing scenes on screen.

She’d rebelled when Mama had insisted she put on lipstick and wear nice clothes, and now she rebelled again. “When I began making movies,” she said. “they fixed my hair and made me up. I who had never put anything on my skin now had a face smeared with thick yellow plaster. It made me sick.” She simply refused to fix herself up or wear pretty clothes, and the producers had to go along with her wishes.

Papa hadn’t let her go out with boys. now she reached out for any man she desired. Her marriage to Roger collapsed after five years because. as she said. his mannerisms were “bound to kill any romance.” She spelled out what she meant. “He picks his nose, snores in his sleep and walks about the Hat half the day in his trouser suspenders, and worst of all he has become more of a brother than a lover.”

After their divorce, Roger had his say. “She prefers,” he said. “most of all and in the following order: her dog Clown, other dogs, birds, sun. money, the sea, dolls, flowers, Empire furniture, fuzzy bears, kittens, toy soldiers and white mice.”

She reached out for the next man, Jean-Louis Trintignant, thirty-five years old and married. even before her divorce from Roger was final. Tin soldiers, she was finding out, melted at her touch. But in her own room she’d been able to keep her toys under control and in their place.

Jean-Louis, however, was a real life, flesh-and-blood man. He was taken into the French Army and sent to Germany, and she lost interest in him. “He wasn’t near me, that’s all,” she said later, in explaining their break-up. “Weekend romances are not enough.”

Like a little girl opening one package after another under the Christmas tree, she turned to one man after another: Italian actor Ralf Vallone, Mexican actor- bullfighter Gustavo Rojo, Gilbert Becaud, guitarist Sacha Distel and Jacques Charrier, the man she married.

Her sexual escapades with these men became front-page news. This was the sensual Brigitte in action, the woman who proclaimed, “I may be dead tomorrow, so I live for today.” The seeker after love who declared, “Good looks and sex appeal are not important to me. A man has to have a soul. If I ant in love with somebody, I don’t care if he is young or old or beautiful. . . . What do I prefer in a man? Mouth, teeth and sincerity.”

This is the sex-charged, seductive aspect of Brigitte Bardot, the body that moves naturally and seductively across the screen and says to every man, “Come here.”

But what of the other part—the petulant face of the precocious adolescent, the pouting mouth and the childlike eyes which say, “Don’t touch.”

This Brigitte still longs for the safety and security of her own room, with the dolls, the stuffed bears, the toy soldiers and pet animals of childhood.

This Brigitte refuses to pose for five minutes when requested to do so by a world-famous magazine but agrees to spend a full afternoon posing with pets for an animal magazine. In a little girl’s voice she explains, “I just love four-footed creatures.”

This Brigitte sucks her thumb, gobbles chocolates between meals and sulks if she’s not allowed to cuddle rabbits, dogs, cats or stuffed animals in almost every picture she makes.

This Brigitte once raced her car at 80 miles an hour along a London highway in pursuit of a big, black limousine. When the two cars halted at a traffic light, she stared out at the woman sitting in the other car. It was Princess Margaret.

Later Brigitte said, “If a cat can look at a queen, surely a ‘sex kitten’ can look at a Princess.”

This Brigitte, when asked, “Suppose you had a child?” before she became pregnant, answered, “Oh, that would add to our troubles. I am such a child myself.”

Brigitte Bardot, the child without a childhood. who ran home to Mama and Papa when her marriage to Vadim and her affair with Trintignant both soured, and slept in her old room still filled with rag dolls, toy soldiers and fuzzy bears. Brigitte Bardot, the child for whom womanhood is too great a burden, who tried to take her own life when the pressures of her marriage to Charrier became unbearable and who cried, as she lay near death. “Mama. Mama. Mama.” Whether she was calling to her mother or to her doll, no one will ever know.

Brigitte Bardot. whose father, carrying a bouquet of red roses, visited her in the hospital when she was recuperating from her near-suicide and gave her an old- fashioned bawling-out. Nurses at the bedside, who affirm that up until that moment their patient had alternated between loud cursing and stony silence, were amazed when she broke down and cried.

Brigitte Bardot, a little girl lost in a woman’s body, who still can’t believe what her mirror tells her. “I’m ordinary, like all girls,” she says. “When I look in the mirror. I see a funny face and I wonder how people can find me alluring. When I was little I thought myself ugly and tried to be inconspicuous. As an adolescent I thought I was thin. Now I think I am what I am . . . In spite of all that’s happened to me I still think as a child.”

Recently in Switzerland a crowd collected while she was making a scene for a picture. Young men and women watching her—people about her own age—threw cigarettes at her and called her names.

A few days later an elevator she was in broke down and she was trapped there with a cleaning woman. The woman screamed at her at the top of her voice, accusing her of every imaginable sin and every possible immorality.

The woman in Brigitte answers back, “I know what they are saying about me. I know and I don’t care.”

But even as she says these words—striking out at the accusations of her enemies and the chidings of her friends and the scoldings of her parents—her face, a child’s face, shows that she does care. The tears which gather at the corners of her eyes indicate that she wants to be back in her own room, away from all these voices, where Mama-doll loves her and Papa-doll understands her and a fuzzy bear can just stand facing a toy soldier without having to say a single word.

—JAE LYLE

Brigitte will be seen in “A Very Private Affair” for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1962

AUDIO BOOK