Marilyn Monroe’s Mother Escapes Mental Hospital

Mrs. Gladys Eley sat staring out at the night as though contemplating the great maw of black and darkness. It was about 2:00 A.M., although in the ten years she had spent living in that room, time was no more than the changing positions of two hands on a clock. She bowed her head after a moment, clasped her palms together and pressed her hands to her breast in prayer. She asked God to please understand what she was about to do.

Then she quietly took the nurse’s uniforms she had obtained, tied the two together with an uncertain knot to make them form a thick but serviceable rope. She raised the window in a small closet adjoining her room and, almost fearfully, looked over the sill to the ground. It was only eight feet down, yet it seemed a long way to this frail, white-haired woman of sixty. She very thoughtfully considered the drop for another few moments.

She took two books, fastened them lightly to the “rope,” and shook them gently to the grass below. Then she carefully tied one end of her escape line to a heavy chair and, that done, put the other end through the window. With an agility that belied her years she climbed over the sill and with the strange new strength of her small hands, she lowered herself until her feet were only a few inches above the earth.

She picked up the books and quickly but quietly walked out through the gateway of the Rockhaven Sanitarium in Glendale, California, and with a firm fast step disappeared into the night.

She walked to the west. For how long she did not know. From time to time she would stop in front of a church, inspect it carefully and then sadly turn and continue on.

When she was tired she went into the next church and rested. With her spirit and body renewed she started out again.

Woman in white

Dawn came, the sun rose and burned its way through the morning into the afternoon. Only a few curious passersby noticed the slight woman in white nurse-like dress. She did not notice them. Her eyes were only for the thing she sought and she could not find it. She spoke to no one but went from church to church clutching the books under her arm.

The sun finally finished with that part of the little woman’s world, descended, leaving the dusk and the night once more. The small woman was tired now. She had had nothing to eat or drink. Her fruitless search had wearied her and she was growing cold.

Then she saw a church that looked more like a well-kept home. She studied the sign on the lawn which told her it was the Lakeview Terrace Baptist Church and that Rev. J. Brian Reid was its pastor.

Inside the dark church she prayed for a few moments and then, as if she had been there before, she walked through a doorway to the rear of the building and stopped before a closet. She opened the door and a soothing, welcome draft of warm air drifted out from a water heater.

She nodded her head, went in, closed the door behind her, curled up on the floor in the darkness and fell asleep.

At 9:15 the next morning Rev. Reid, on his way to his study in the rear of the church, found the woman sitting on the steps.

She arose as he approached and with just the bare trace of a sad smile said, “If you are Rev. Reid, I’ve been waiting for you.”

The pastor said he was Rev. Reid.

“She was very calm and cool,” Rev. Reid said. “And she was, without reservation, the kind of a person to whom your heart goes out.”

The minister asked if there was anything he could provide for her in the way of help or counsel. He would like to help.

“I am looking for my church and I cannot find it,” she said. Deepening lines of anxiety had come unexpectedly to her face. She shook her head and stared at the new daylight around her. She watched a bird stropping its bill clean on a tree branch.

She turned back to the minister and in words that seemed as a prayer, said. “I need someone to be with. It is very lonely. She dropped her soft grey eyes to the ground and then let them fall on the two books she had under her arm. The thicker of the two was a worn, leather-bound Bible. The second was a Christian Science handbook.

“I am Mrs. Eley,” she said. “Mrs. Gladys Eley and I am studying to be a practitioner in my Church.”

She looked back toward Glendale, twelve miles away.

“I had to leave there, you know, I could not study properly and I have fallen behind on my way to God.” She hesitated for a moment. “It was cold during the night and I saw how peaceful and inviting your Church is. I had no place else to go.

“When I went inside I knew it was a true place of God, for He spoke to me. You see. He knew I was cold.” She smiled. “It was nice and warm in there by the heater.” She looked back at the Church. “God is always ready to help us when we need Him,” she murmured quietly.

She threw back her head and staring directly at the pastor said, “Could you also help me find my daughter? The one that is alive?”

Rev. Reid nodded. “I will do what I can to help you, Mrs. Eley. But perhaps we’d better go inside and I will call your friends.” They started in to the study.

A daughter “gone”

Mrs. Eley did not speak, but she shook her head sadly. “I had another daughter,” she said suddenly. “But she has gone to God. I pray for her spirit.”

Then, quickly, she asked, “Do you know Marilyn Monroe, the actress, was my daughter? I am her mother. Marilyn . . . she has left . . . they told me about it after it happened. She was very, very lovely. They say everybody liked her. People all over the world watched her in pictures.” Mrs. Eley shook her head again. “But I don’t think she was happy. She used to come to see me, but she won’t come anymore.

“People ought to know that I never did want her to become an actress. I was always against it. I did not see her much when she was a little girl because I was ill. They said she was pretty, even then.”

She fingered the white uniform she was wearing.

“She was kind, too. They say that before she left, she thought about money for me. Every month, they say, from what she had they give me something.” Tears threatened to come to her eyes.

“She did not have to do that. She must have known God would take care of me. He takes care of us all in the end. I do not want the money. I wish they would take it and give it to someone else, to people who need it more than I do or use it for some other purpose.

“People should know about that. I didn’t want her to be an actress in the first place. Her career never did her any good.” Somehow, she fought the tears back.

“It would help, Mrs. Eley, if you’d tell me where you came from,” the pastor asked gently.

“I knew you’d want to know that,” Mrs. Eley replied. “I don’t want to tell you. I’ll have to go back. There is no one there I can—”

Mrs. Eley dropped her eyes and clasped her hands.

“I’m from the Rockhaven Sanitarium,” she said, just barely above a whisper.

The law takes over

The minister called the sanitarium. Yes. Mrs. Eley’s disappearance had been reported to the Missing Persons Bureau. They would send for her.

Rev. Reid dialed the police. He was connected with Officer John Sherwood of the Foothill Precinct of the Los Angeles Police Department. He explained carefully that he was with a Mrs. Gladys Eley, who had apparently wandered from the Rockhaven Sanitarium in Glendale. Sherwood dispatched Officer James Wilson to the church in a police car. . . .

Two police women greeted Mrs. Eley at the station. Officer Sherwood talked with her for a while and explained gently that she must go back to the sanitarium.

“Your daughter was a very beautiful and lovely woman,” one officer told Mrs. Eley.

“Yes,” Mrs. Eley replied quietly, staring at the activity around her.

The uniforms and brass buttons and the shields of the officers seemed to frighten her.

“Don’t be afraid,” said another policeman. “You mustn’t be afraid. You are safe. After all. Marilyn, your daughter, was once married to a policeman.”

Mrs. Eley looked at him. “Yes, I know.” she said.

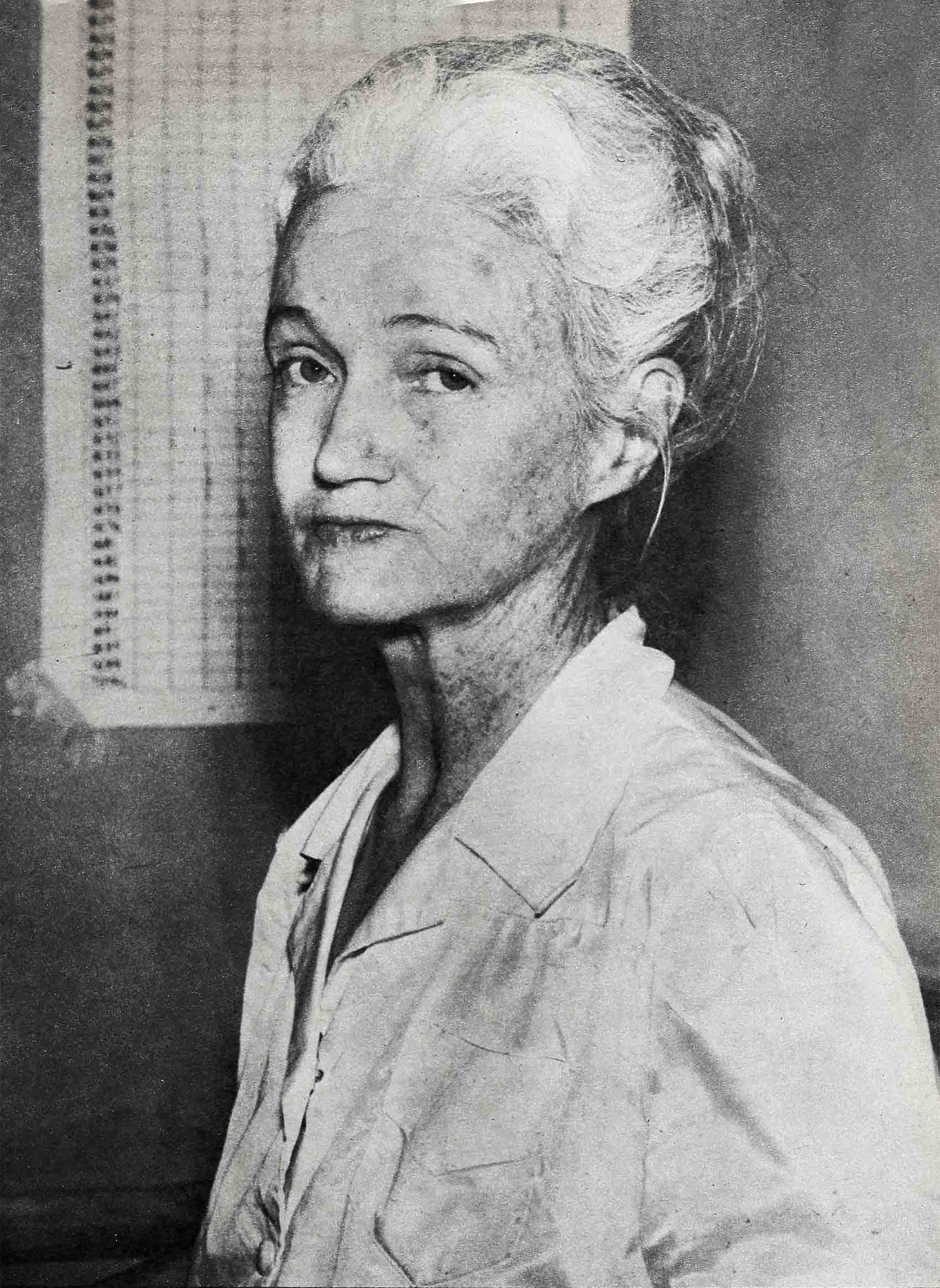

Just then Louis Diesbeck, a photographer from the Glendale News-Press, appeared with his camera.

Mrs. Eley shook her head. “No, no,” she said tearfully, “you must not do that. I am a Christian Scientist. My religion forbids me.”

Diesbeck smiled. “It’s all right, Mrs. Eley. I am a Christian Scientist, too. I won’t do anything wrong.”

Diesbeck’s photo was the first clear picture of Marilyn’s mother the world has seen in more than a quarter of a century.

Just before the representatives of Rockhaven came for Mrs. Eley, a strange thing happened. Flanked by members of the Rockhaven staff, Mrs. Eley stopped in the doorway of the police station for an instant and turned to look at the swarming crowd of reporters, policemen and television cameramen who had sped to the scene.

She let her gaze go from one to the other as though making a plea to each person.

One reporter remembers it vividly. “I’ve seen that look on a thousand faces, but I never expected to see it on the face of Marilyn Monroe’s mother,” he said. “That look says—‘Please, for God’s sake, help me.’ ” It was a look he’d never forget.

The reporter wasn’t the first or only observer to make similar remarks. In our discussion of Mrs. Eley, Rev. Reid himself was outspokenly concerned with Marilyn’s mother’s plight.

He said: “Here is a sweet, kindly and Godly woman who has been put away so that she will not get in anyone’s way. All she needs is what every individual in the world yearns for, to be loved and wanted.

Can we help her?

“This is what breaks my heart. No one can do anything about it because I presume that she was committed by a due process of law. Perhaps the publicity and this story will suggest that Mrs. Eley’s case be studied a little more carefully.

“Mrs. Eley’s only apparent concern at the time was that she was going to have to go back to the sanitarium. But the impression I got was that she dreaded going back to loneliness.

“She showed no anger, no resentment, no bitterness, no violence. She displayed no psychotic symptoms of being out of her mind. She wasn’t vicious or any of the things that you might note in a mentally disturbed woman.

“She was only very obviously lonely and in search of someone to care for.

“I feel that if Mrs. Eley could be welcomed in a home, a real home where there is a family, where she could be shown some respect, where she would feel that people want her around and if she could be made to feel that she was doing some good and helping someone, she would be a happy woman. She is not any more disturbed than any other human being in the same situation.

“All of this, of course, is my opinion and though I am not a psychiatrist. I have been trained in psychology.

“Mrs. Eley’s case has been very much in my heart since I met her. I hope something is done about it before too long.”

A lonely woman

The real purpose of Mrs. Eley’s “confinement” has never been made quite clear. The usual report has been that she is “mentally disturbed.” So it must be presumed that the true reasons for Mrs. Eley’s commitment to a sanitarium are deeper and more serious than the exposure during her “escape” revealed.

But today, restricted legally within the bounds of sanitarium grounds, Marilyn Monroe’s mother is lonely, longing desperately for a pitifully trivial opportunity to communicate in her own way with God and yearning, with her heart in tears, for the chance to love someone who loves her.

With God’s help that day may come.

But until it does she can only wait, for all she has left is hope.

—BY WHIT PRESTON

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1963

zoritoler imol

31 Temmuz 2023Well I definitely liked reading it. This post procured by you is very useful for accurate planning.