Patty Duke & Sue Lyon

It’s Saturday afternoon. You and your boy friend stroll down to Main Street to take in a matinee. You want to see the movie at the Orpheum and he wants to see the movie at the Strand. But before the argument between you gets really hot, he comes out with a brilliant suggestion. “C’mon, l’m flush and I believe in spreading the loot around. Let’s give ’em both a break, shall we?’’

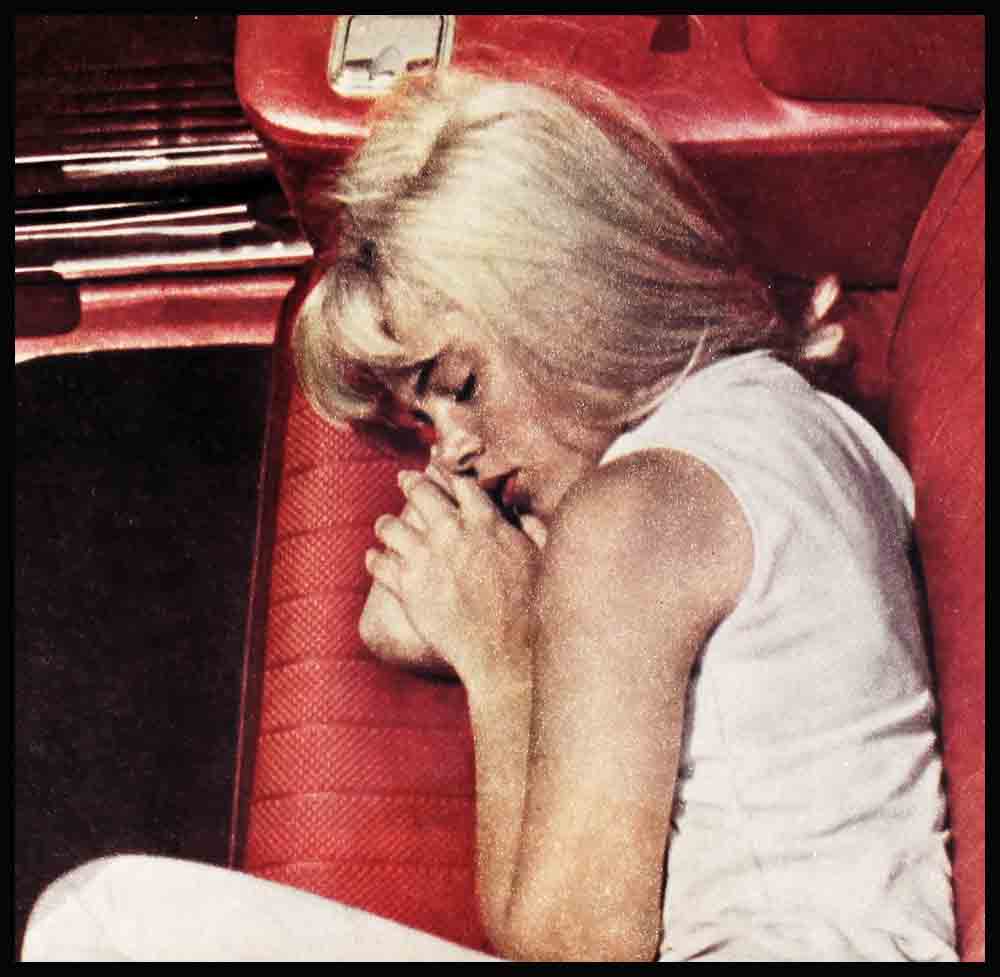

In the darkness of the Strand you pass him the popcorn and he passes you the salted peanuts while you both stare up at “Lolita.” She is lying on her side, propped on her elbow, flipping through the pages of a magazine. On her head she wears a wide-brimmed picture hat from under which bangs peep; covering her eyes are dark sunglasses—heart-shaped, absurd. Next to you, your boy friend sucks in his breath and you know for sure that he’s not looking at her face. Maybe you shouldn’t have let him be so generous—settled for the Orpheum. But even while you’re thinking these things, you have to confess—only to your- self, of course—that the curves of her slim figure, set off by a very brief bikini and outlined against the lawn, are kind of nice.

It’s when the girl on the lawn pushes her sunglasses up on her forehead, how- ever, that you move in closer to your boy friend to let him know you’re still there, too. Because now you see her eyes (slate-colored? bright blue?—you wonder which) gazing directly at a man whose own eyes are fixed on hers in pure (or maybe it’s impure) fascination. And her gaze . . . shy . . . bold . . . pert . . . sullen . . . provocative . . . disinterested . . . you’re not certain which (perhaps it’s all of these and more), disturbs you.

The exact word to describe her comes later, haltingly, from your boy friend as you and he stumble out of the dark theater into the bright sun. You’ve asked him how he liked the picture, and he stares down at his shoe tips and blushes as he answers, “That Sue Lyon— she—she’s—well, what I mean is—she’s sort of— sexy, don’t you think?”

A few minutes after this, you and your boy friend are seated side by side in the Orpheum watching “The Miracle Worker.’’ The chocolate bar he bought you is sticky in your fingers—you’re hypnotized by the scene on the screen. There, a little slip of a girl is battling furiously with a woman. The expression on the girl’s face is amazing—her eyes are glassy yet wild, her mouth is violently distorted so that she looks like an untamed animal; her hair flops and wiggles as if it had a separate, uncontrolled life of its own. You’re a bit ashamed as you say to yourself, ‘Well, at least Patty Duke isn’t sexy For even pretty.”

You shush him—and keep your attention on the screen. A transformation is taking place. The little blind girl on the screen has thrown a pitcher of water at the woman—her teacher —and now the two of them are out at the pump where the child is refilling the pitcher. As the girl pumps, the woman spells out the word ”water” on the child’s hand, using deaf and dumb —and blind—language.

And the girl’s face! It’s like nothing you’ve ever in your life seen! Where a moment before her hair was like a shook-up mop, it now softens and frames her face; a moment ago her eyes had resembled an animal’s at bay, now they have the expression of a child seeing her first Christmas tree; her mouth was ugly and jagged—now it shapes itself into something almost beautiful as it forces out the sound “wau-wau”—water!

“Beautiful”—that’s the word for the little girl’s innocent heart-shaped face as one tear forms in the corner of her eye and then courses slowly down—down her smooth cheek. And her lips, in that magical second of enlightenment, understanding and self-realization, curl into a sweet tiny smile.

As you leave the movie your boy friend says, “You know, that Sue Lyon—I bet in real life she’s Miss Innocence herself. And Patty Duke—who knows, in real life she might run around with more guys than anyone in her crowd. Actresses fool you . . .

You explode, “That’s silly! An actress can’t turn on an emotion or play a part if she didn’t have some experiences like that in her life! Sue Lyon must be something like Lolita and Patty Duke must be sweet and innocent.” And you insist, “I’ll bet I’m right—only there’s no way to find out, really . .

How to tell . . .

No way? Oh, but there is! A simple way —you talk to the stars in question, you talk to their friends, and you read what people who know them have written about them. You put all your findings together, and you reach certain conclusions: What kind of a girl is Patty. What kind is Sue.

When we talked to each of the girls, we put similar questions to them. And the answers—well, that’s our story.

Our first question: “Why were you selected by the producer to play the lead in this picture, and what did you have to do to get the part?”

SUE LYON. The need for money—to make life easier for her widowed mother and for her three brothers and her sister—turned twelve-year-old Sue’s footsteps towards show business. Sheer luck—and the fact that she looked like what the producer thought Lolita should look like—won her the role of the preteen temptress.

It was her older sister Maria, knowing how hard it was for their mother to support all of them on her wages as a hospital housemother, who first took Sue on the rounds of photographers’ studios and TV stations. Sue appeared on TV in bit parts in “Dennis the Menace” and “The Loretta Young Show” and graduated to doing a cosmetics commercial.

Not exactly the background and training to prepare her for the most sought-after role for a teenager in movie history. But then again, Sue was driven on by acute financial need and, perhaps, by the deep, barely conscious feeling that someplace, somehow, her father, who died when she was ten months old, would be proud of her.

The miracle happened. As co-producer and director Stanley Kubrick tells it: “From the first, she was interesting to watch even in the way she walked in for her interview, casually sat down, walked out. She was cool and non-giggly. She was enigmatic without being dull. She could keep people guessing how much Lolita knew about life. When she left us, we shouted to each other, ‘Now if she can only act!’ ”

A screen test proved she could act. The year-long search for Lolita ended when Vladimir Nabokov, the author who had originally created the character of the sub- teen, bubble-gum-chewing seducer of older men and had then re-created her in the screen story, was bowled over by Sue and pronounced her “the perfect nymphet.”

In Venice, a PHOTOPLAY reporter asked Sue, “How did you get this part?”

A: Well, I went on interviews for it—and then I did a reading and then I did a screen test with Mr. Mason.

Q: That was it?

A: Yes, that was it.

Q: How many girls tested for the role?

A: I don’t really know—some say 500, some say 800. I’m not sure.

That’s the only thing that Sue doesn’t seem sure of. As for everything else, she seems as sure of herself as the producers and writer were that she was Lolita.

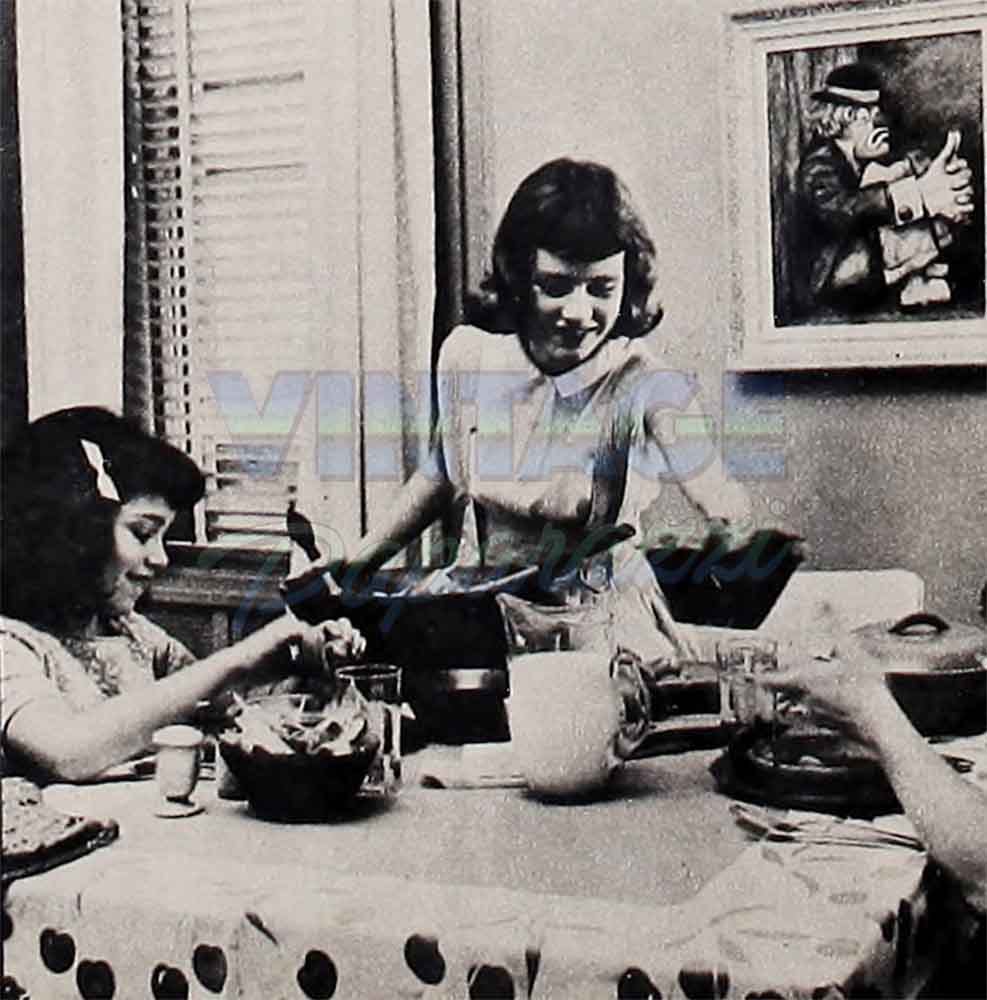

PATTY DUKE. The fact that fifteen-year-old Patty Duke is an actress is apparent as soon as you enter the New York apartment of John Ross, her manager, and see the white packages of matches, embossed in gold with her name, lying casually on the table. But this fact, like so many other “facts” relating to her, turns out to have a completely different significance as soon as young Patty starts talking.

She hadn’t ordered the matches made up for her especially; on the contrary, they were given to her by a hotel in Atlantic City where she and the Rosses and “five other children” sometimes go to swim and to get away from the city.

“If you had any three wishes in the world and you were guaranteed they would come true, what would they be?” I asked.

“I’d want to go on with my career and have it be very successful; I’d want my new TV series, ‘The Patty Duke Show,’ to be a big hit; and—and—”

“Yes?” I said, both pleased and disappointed that Patty Duke seemed completely caught up in her career.

“I’ll tell you later”

“And—I’d like to think about the third wish and tell you later,” Patty said with a sweet smile.

When the third wish did come—much later in the interview—my notion that Patty was a career-obsessed little girl was also to be shattered.

But for the moment the problem was to find out why she was selected by the producer to play young Helen Keller in “The Miracle Worker.”

Like Sue Lyon, pressing financial need had turned Patty to show business. Patty’s mother had to work in a restaurant to support her three children. So that when the little girls’ older brother Raymond told his sister that some people called the Rosses wanted to met her, and that if everything went all right they might be interested in helping her to become an actress, she jumped at the chance. May be she could make some money and give it all to her mother—well, almost all, there might be a little bit left over to buy herself one pretty dress.

What Patty didn’t know—and what Raymond. who had originally been sent to the Rosses by the Madison Boys’ Club to take speech and dramatic lessons in the hope that this would save him from becoming a juvenile delinquent, didn’t tell her—was that her brother had said to the Rosses, “Well, some people think my sister is cute. I don’t think so—but I’ll bring her around.”

She wasn’t yet ten when she showed up at the Rosses’ place. Her lıair vvas a strag- gly ınop; her clothes were ill-fitting hand-me-downs; her speech left something to he desired. She asked, “Kin oi have one uh dem muhstid samwiches?” Nevertheless, she was cute.

She was scared, too, until John Ross asked her to do a pantomime. Then everything was okay. Acting as if she were somebody else, actually being somebody else for a few minutes, was fun. For while you were someone else, you didn’t have to remember that your father, a New York cab driver. had deserted the family when you were eight and you hadn’t seen him since; you didn’t have to remember that your mother worked long, hard hours in a restaurant; you didn’t have to remember that sometimes when you played in the New York streets with the other kids, you were so hungry that a piece of bread could seem as wonderful as a birthday cake. By playing parts. your dreams could come true.

Ross liked Patty’s pantomime, and soon she was studying and working with him steadily. As her speech cleared up, she began to play parts on television and in movies: in the TV version of “Wuthering Heights” and in the New-York-made films, “Happy Anniversary” and “The Goddess.” In every production she was somebody else.

The resemblances between Sue Lyon and Patty Duke stop when it comes to how they first got their big break. Patty was twelve years old when she won the part of seven-year-old Helen Keller in “The Miracle Worker”—the same role she later played in the movie. Yet her ability to be the little blind girl flowed out of her studies with her dramatic coach, her experience on TV and in movies, and her specific preparation for the audition. And, although possibly she didn’t know it. out of her own underprivileged childhood.

A year and a half before the play was to be cast. Patty and Mr. Ross began working on the part. She read all the books by and about Helen Keller. (Sue Lyon, on the other hand. says that she skimmed through the book, “Lolita,” but has never finished it. This “skimming through” is exactly what Lolita herself would have done if someone had handed her a big, fat, forbidding book and said. “You must read this.”) Patty stumbled around the Rosses’ apartment, eyes closed, to get the feel of being blind. Occasionally, the Rosses tricked her and rearranged the furniture, but that only added to the illusion that she was really blind.

To pretend she was deaf was a little harder. Perhaps if she imagined that she was out playing in the streets and the kids were teasing her and she couldn’t stand what they were saying another moment, she might be able to retreat from the noise of the world. But just as she was getting the hang of it, Mr. and Mrs. Ross would ask, “Want a coke, Patty?”, and she’d give herself away. She heard. It was hard.

After a while. however, nothing stood in the way of her being Helen Keller. Helen Keller was deaf, Helen Keller was dumb, and Helen Keller was Patty Duke, closed off and shut out from everyone else. When it came time to audition, the producer didn’t meet an actress; he met seven-year- old Helen Keller, who once in a while played at being twelve-year-old Patty Duke. And, of course, she was signed immediately to a contract.

The second question asked both girls, “Does your personal and profession life fuse and get you confused?”

SUE LYON. From the moment Sue Lyon walked into the casting office, and producers Stanley Kubrick and James Harris blinked at each other and exchanged the unspoken message, “This is Lolita,” she has been defined by others as being Lolita, on and off the screen. In this she is not alone. People who meet Jayne Mansfield in the flesh can’t accept the fact that she’s not just that, all flesh, and they try their darndest not to admit that she’s a sensitive, college-educated gal who can utter something else besides baby-talk. Then there’s Raymond Massey, who was identified for such a long time with his stage and screen depiction of Abraham Lincoln that, up until two years ago. strangers would stop him on the Street and whisper, “Hey, Abe, whatever you do, stay away from Ford’s Theater.” More recently, women in supermarkets, refusing to believe that Massey is not Dr. Gillespie, confront him with requests as, “Doctor, I’ve been bothered by varicose veins. I wonder if you . . .”

Mrs. Sue Karr Lyon, Sue’s mother, has stated succinctly the dilemma facing her daughter. “The thing that worries me,” Mrs. Lyon confesses, “is that people may confuse my daughter with that slimy character she plays.”

Mrs. Lyon’s fears have a solid basis. She has publicly expressed the hope that “the PTA won’t cut me to pieces. When I went to school to pick up Sue’s books, her teachers were very, very cool to me.” And Sue says bitterly that the parents of some of her friends “are narrow-minded and say the wrong thing.”

Newspapers do their part to foster this “Sue Lyon is Lolita” reaction. Recently, for instance, under the banner headline “Sexpot Symbol Race Is On.” Sue was nominated—along with such high-voltage symbols of sex as Stella Stevens, Ann-Margret, Julie Newmar, Jane Fonda, Barbara Eden and Claudia Cardinale—as the most likely candidate to succeed Marilyn Monroe as “pinup for the world.”

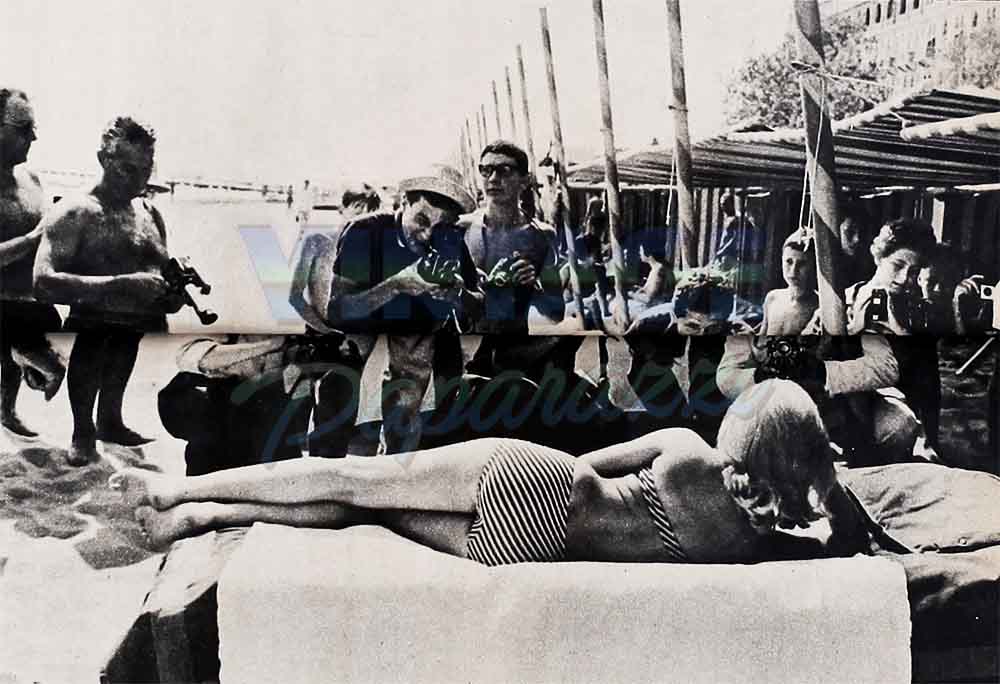

It must be said, however, that there is something about the way Sue walks, talks, acts and reacts which encourages this sort of typecasting. At the Venice Film Festival, for example, she fed fuel to the newspapers by declaring that she would like to play the lead in the life story of Marilyn Monroe. (This was the day after the night that she finally had secured a special police permit to see herself on-screen as Lolita; previously, 16-year-old Sue was kept out of the New York premiere by a rule for- bidding the showing of the film to minors.)

When asked whether her published quote about wanting to play Marilyn was accurate, Sue replied, “Well—the question was, ‘If you had to play one celebrity, who would you choose?’ And I guess her name was most prominent in my mind.” To the rejoinder, “That would be pretty good casting!” Sue said. “Thanks.”

Is Sue, in fact, describing herself and what is happening to her, as the Lolita-image begins to jell? It is certain that she can’t do anything about (and who would want her to?) hiding her natural beauty. “When she was thirteen,” writer Liza Wilson says, “Sue blossomed out into a young beauty with blond hair and huge blue eyes and a figure that caused boys in the school yard to whistle.” But she can do something about jumping off the personal appearance, party-going, publicity treadmill she’s on and returning to solid earth, before it’s too late.

Fame has changed Sue

Fame (perhaps the better word would be “notoriety”) has already changed Sue. Jon Whitcomb finds her “a monument of composure and self-assurance” and recalls that other young stars he knew at the beginning of their careers (Sandra Dee and Tuesday Weld, to name two) “were children by comparison.”

Just before her sixteenth birthday, Sue presided at a party in her honor at the Tower Suite in New York City, immediately following the premiere of “Lolita.” She couldn’t attend the premiere because of her age, so she slipped away to a beatnik coffeehouse in Greenwich Village. Then came back for the party—most mature in a sophisticated dress—and shook hands with 500 celebrities who were congratulating her as if she’d been in the limelight all her life.

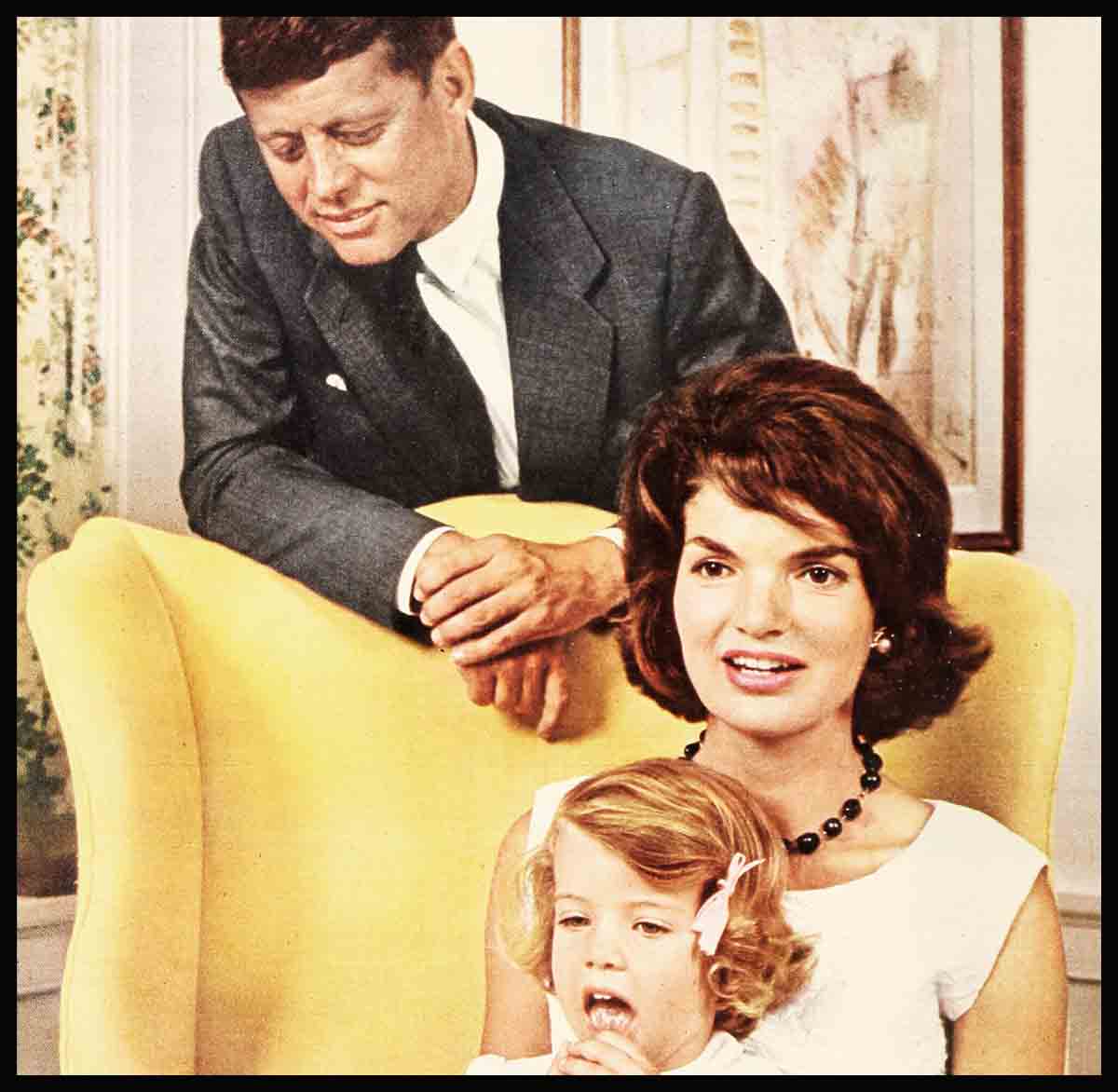

The star-treatment—can Sue survive it? At the Grand Trianon room of the Beverly Wilshire Hotel at a party after the Hollywood and West Coast “Invitational Preview” of “Lolita,” Sue was asked to pose again and again with Vince Edwards, even though Vince’s steady girl, Sherry Nelson, was sitting nearby. The following day, of course, the papers were full of a “romance” between Lolita and Ben Casey. At the same party, George Hamilton left his fiancee, Susan Kohner, walked over to Sue, kissed her hand and danced away with her. A few days later the Kohner-Hamilton engagement was broken off.

The pattern of that evening as recorded by Sidney Skolsky (“Sue is photographed almost as much as she is in ‘Lolita.’ Sue Lyon is sitting. Standing. Bending. Smiling. Pleasant. Sitting. Standing. Shaking hands. Sitting, etc.”) is repeated in London, Venice, Tokyo, Sydney, Melbourne and Honolulu during her world tour of personal appearances in connection with international openings of the film.

When asked, “Doesn’t it bother you, losing your privacy this way?,” Sue answered, “I haven’t lost all of it.”

In two respects, at least, Sue is cut out of the same cloth as her silver screen counterpart Lolita: in her attitude towards money and in her reactions to school and culture. To the question “What do you like best about work?”, Sue answers bluntly, “The money. It’s the quickest way I know of to make a lot of money, fast.”

While she’s definite about money, she’s diffident about school. Once upon a time, before “Lolita,” Sue went to Micheltorena Elementary School and to Starr King Junior High. But she wasn’t much interested in classes and goofed off to the movies.

Public school’s behind her now. Because she travels so often, she has a private tutor (she is a whiz in math, but hates foreign languages). Does she miss the old gang with whom she’s lost contact during the last two years? Not much. Sue says, “I see them sometimes. They accept me same as ever. No big deals. Of course, there are always a few who are impressed. The new kids I meet seem to think I am conceited.”

What did Sue do during her spare time and on weekends while she was on location making “Lolita” in London for five months? Well, she went to movies—just as she’d done back when she was in public school. And she took up horseback riding.

Museums? She feels about them as she previously felt about reading the novel, “Lolita.” Nothing. Her mother confesses that Sue was “bored stiff at the Louvre,” while daughter chimes in with a line worthy of Lolita, “I’m not much for sight-seeing or going to the statues.”

Lolita and Sue, Sue and Lolita. Sometimes they’re interchangeable. As writer Jack Hamilton says, “She seems to have the same sly, secret joke against the adult world she invested in her character of Lolita . . .”

PATTY DUKE. It can be safely said that Patty Duke in real life is very much like the character of young Helen Keller who broke out of a world of wildness and strangeness and was transformed into a child of sweetness and innocence.

So close did the young actress feel to Miss Keller that during the run of the play she made a special pilgrimage to the blind woman’s home at Aachen Ridge, Connecticut. This was the high point in Patty’s young life, and when she talks about it today, her eyes light up.

“When we came to the door,” Patty recalls, “a nurse answered. Miss Keller hadn’t seen any other people for a while, and she was just dying to communicate with someone.

“Suddenly. I heard a movement on the stairs. I looked up and saw the most wonderful thing. There was Miss Keller coming down the staircase alone. She was so graceful. so beautiful. She was wearing a blue dress, a string of pearls, a lovely pin and a pair of red shoes. Her white hair was beautiful, but the thing I remember most are her eyes. Happy eyes, laughing eyes. And I realized that although she was blind she could see everything.

“I spoke into her hand with my fingers, using deaf and dumb language. I told her how much I liked her red shoes. She was delighted. Of course, she’s never seen red shoes, but people tell her red shoes are pretty so she wears them whenever she dresses up for company.

“We walked around her garden and she would touch each plant, flower and tree and then tell me its name. She showed me where she had just planted tomatoes.

“With my fingers, I told her about my dog and my schoolwork and about how I like chocolate cake. I asked her about a lovely light burning in her garden, and she answered that it was an Eternal Light that was always lit, a gift to her from the people of Japan.

“When I finally left her, I couldn’t get out of my head the memory of how youthful and exciting she was at eighty—and how much she does for other people by just being alive. Maybe I can be a little like her and make others happy, too.”

Actually, Patty is a lot like Helen Keller. Making other people happy is as natural to her as breathing. She gives lectures at the Lexington School for the Deaf and visits elderly people at the Lighthouse for the Blind. At Quintano’s School for Young Professionals, which she now attends, she is studying Italian. French and Spanish so that she can “communicate” with more people.

Patty’s attitude about being a celebrity is modest and unusual. When asked ‘‘Are you recognized often?”, she laughed openly and warmly and answered no. “Sometimes I see people staring at me at bus stops and things—but mostly after a minute they shake their heads and I can see them thinking, ‘No, it’s not.’ ”

“But now that the ‘Miracle Worker’ is a smash hit,” I told her, “you probably won’t be able to walk down the Street without being stopped for an autograph. Will you mind that?”

“Oh. no,” she replied. “I like people. I’ll enjoy it.”

Okay, okay, I thought, there’s little doubt that you are the same innocent, sweet girl you play on the stage and screen. But just to make sure, I sprung the surprise question. “Some columnist said you were considered for the lead in ‘Lolita’? What about that?”

Patty didn’t blink an eyelash, but her voice showed her infinite patience with interviewers who ask silly questions. “No, no, no—it’s not true. Remember, I wore a size 8 children’s dress at the time. Me as Lolita would have shocked everyone. Physically it would have been impossible.”

The third question asked both girls: “Is there any parallel between the feminine image you create on-screen and the way you feel and act towards boys off-screen?”

SUE LYON. At home Sue Lyon wears what almost every other teenage girl wears (loose-top blouses, blue jeans or Capri pants, and play shoes) and acts like Miss Average Fifteen-Year-Old (laughs and giggles constantly; tucks one leg under the other as she gossips on the telephone).

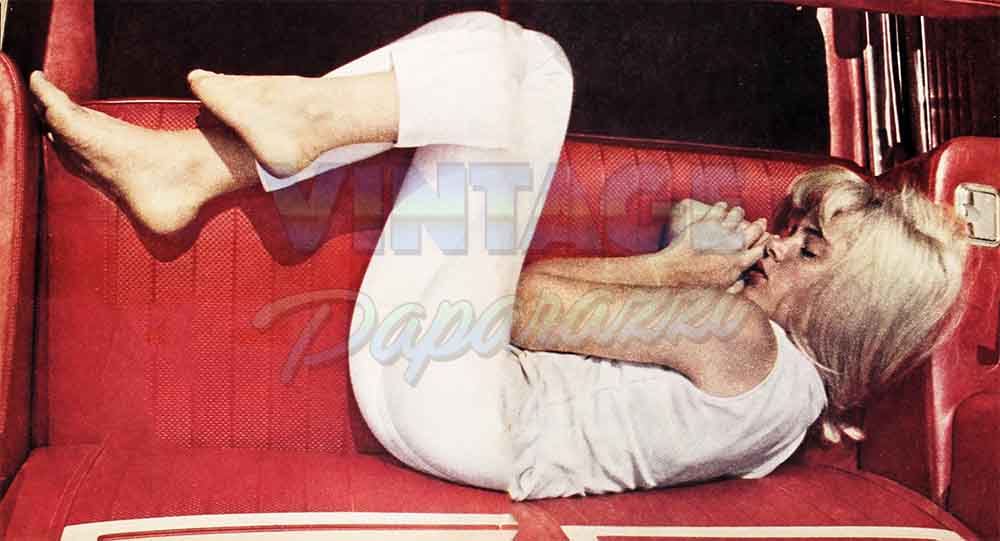

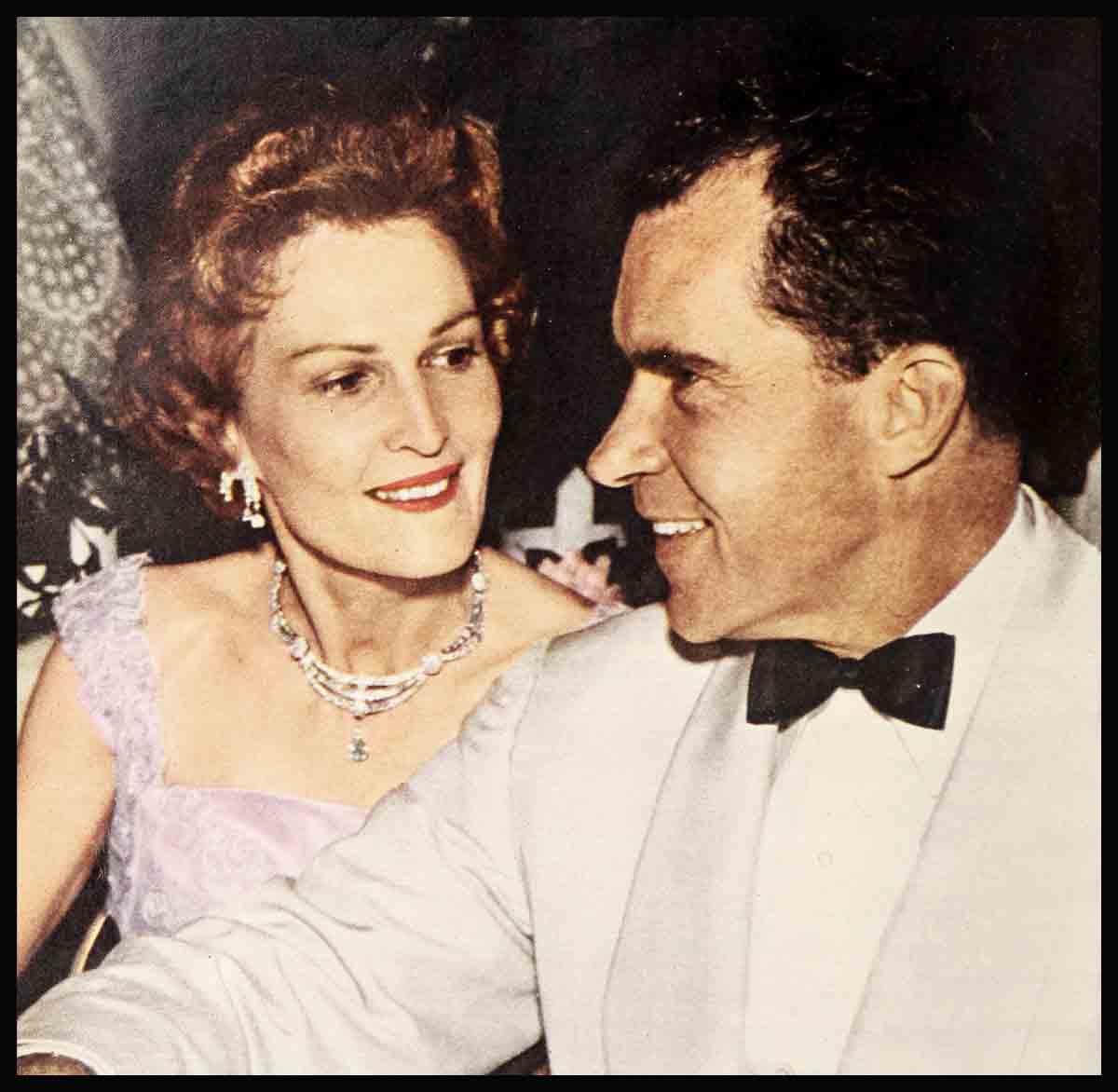

But out of the house on a date—wow! Her baby beige, Bardot-cut blond hair shines (“I had light hair, but I lightened it even more. A real blond stands out better.”) and her figure is sheathed in a form-fitting, specially designed dress. (At first she had doubts about the kind of clothes White House favorite Oleg Cassini would dream up for her. “His dresses seem to be so straight up and down,” she pouted. “I hope I don’t come out looking like Jackie Kennedy. That would be too corny.”) She drives a brand-new, sparkling Chevy Nova—a white convertible with red upholstery (she passed her driver’s test on her sixteenth birthday; the day before, she declared, “If I don’t get it, I’ll kill myself”) and tries to stay within the speed limits, although she confesses, “Every once in a while I scare myself.”

She insists she only goes out with boys who are sixteen, seventeen and eighteen and claims, “I have about four I go out with regularly. The situation changes from p week to week. I don’t go steady. When they try to tie me down, I lose interest. When I fall in love it will be different.”

She admits that one boy, a ninteen-year-old, has given her a hard time since she was picked to play Lolita. “He was a friend of my brother Chris,” she says. “When he called up my brother, I’d go hot and cold. I begged Chris to ask him to ask me out. Chris did, but he refused. I was sick.

“He called me up after I got the movie and we had a date. It was terrible. He must have read the book. He acted as if he were scared to death. We drove up and down the coast for four hours looking for a beach party and he didn’t even try to kiss me. I tore up his picture after that. I hope he reads this.”

But about Chris and his recently-discovered talent for acting, she’s excited. “I’ve heard him read and he does just beautifully. I was so surprised when he began taking lessons—I didn’t really believe he could act—and he’s fantastic. I think he’s better than any young personality today. He just got an agent and he’s going to start working now, I hope.”

Although Sue recently disassociated herself from Lolita by stating flatly, “I’m just not interested in older men,” her statement may not be wholly accurate. She admits to having had a crush on an older man. a Science teacher, but her feeling towards him evaporated when he gave her a “C” when she thought she deserved an “A”. Her “ideal” man. interestingly enough, is an older-man composite: “He would have to look like Paul Newman (thirty-seven), be as kind as James Mason (forty-plus) and sing like Frank Sinatra (forty-five).” She has been linked romantically with Mason. To this Sue answers tartly, “It’s ridiculous. Mr. Mason was very kind to me on the picture. I was four-teen then, you know.”

More persistent has been the report that Sue has flipped for James Harris (he’s the one who gifted her with that snazzy convertible on her sixteenth birthday), and up to now she hasn’t denied it. Dorothy Kilgallen put it this way: “Sue Lyon, the pretty star of ‘Lolita,’ has bowled over her producer James B. Harris. Her age is sixteen, according to her studio, and he’s an old man of thirty-three. She prefers the company of mature men. and James may be just her cup of tea when she’s a little older and he decides it’s proper to court her.”

PATTY DUKE. Patty’s third wish—the one she couldn’t make early in the interview—came bubbling out near the end of it, after we’d become good friends and she knew she could confide in me. “I wish—I wish I could be a little bit taller,” she said. And then she blushed as if she were revealing a terrible secret.

Of course, it isn’t a secret at all. She is fifty-seven inches tall (four-feet-nine) and very conscious of the fact. Because of this, because of her feelings about her lack of height, she has never had a real date and has never kissed a boy.

Well, almost never. There were those two grammar school proms, one of which she attended with Joey (he was in the eighth grade and she was in the seventh, and he invited her) and the other which she went to with Dicky (now she was in the eighth grade and it was her prom, so she invited him). The two proms fuse together in her memory: to one she wore a pretty soft pink party dress (little-girl size-7) and to the other she wore a white- eyelet dress with a blue band and bow. After one they all went to a restaurant and ordered chicken (it was kind of awkward—they didn’t know if they should pick it up with their fingers or not, and ended up not eating) and after the other they went out for pizza. But Joey and Dicky, even though they were spiffed up in white dinner jackets, were more like her brothers than boy friends (after all, they too were students of the Rosses), so if she did kiss them, it hardly counted.

When Patty recalled the kisses she had received from Vince Edwards (twice on the cheek) in a “Ben Casey” episode, she first insisted that it, too, was all part of playing a role. But then she added, and she giggled a little as she said it, “But that was different. That was very nice.”

No for-real kisses. No actual dates. Definitely no boy friends. Yet.

She doesn’t smoke, has never sneaked a cigarette, and has no desire to (“Don’t people who smoke try to break the habit?”) ; she doesn’t wear makeup, not even lipstick (“I’m not ready for makeup yet. Maybe I look strange without it, but I think I’d look funnier with it.”) ; she wears knee socks to school (“They’re so practical!”) and her idea of fun is to go to the movies with a bunch of kids from her class (“We don’t pair off, we all go together.”) or to join in an egg hunt with the boys and girls she became friendly with while doing “The Miracle Worker” on Broadway. (“They put blindfolds on all of us to make it fair for the blind children who can’t see. They lead me. When you can’t see you can’t tell the colored children from the white. You just have a great time and color makes no difference.”)

But Patty’s notion of fun may be changing rapidly. Indicative of her desire to make her wish to be taller come true is the fact that she’s just bought her first pair of high heels. Well. not “high” exactly, just spectator pumps with one-inch stacked heels—but they’re a step in the right direction.

The direction, of course, is towards boys (“I’m looking forward to dating when I’m a little older. Honestly, I like boys. They’re very nice,” she says towards the end of our interview) ; and the boys, it is certain, will find her beautiful—not just because of the way her soft, light-brown hair caresses her heart-shaped face and of the way her blue-green-hazel eyes (they assume different color depending on the dress she’s wearing) crinkle and beam as she talks, but also because of the way her whole personality breathes innocent expectancy, sweet curiosity, as if she—like young Helen Keller discovering the mystery of water—is about to step out and discover the joys of being a girl.

So there you have it—a portrait of two girls—Patty and Sue. The good girl and the bad one? Ah no—we refuse to fall into that trap! You’ve been given all the evidence, and it’s for you to decide whether Sue Lyon is Lolita and Patty Duke is Helen Keller—or whether both of them are superb young actresses who can create a part out of thin air, imagination, or whatever it is that makes an actress. You decide for yourself!

—PAUL ANTHONY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1963

No Comments