Brian Donlevy: “I’m Like This”

I’m a guy who loves to talk about himself—to himself. It’s not an act with me, a slathering on of modesty. For the record, I never was a shrinking violet. I just don’t happen to like to talk about me—except to me.

Just let someone say the word “interview” and I dry up—like a friend of mine on the local ration board when anyone sidles up to remark how short he is of gas.

Faced with an interviewer, the perspiration starts out on my forehead; I find my fingers getting into fists; my leg muscles bunch—that’s how uncomfortable I get.

And all my reactions are wrong. I can’t think of a thing to say. I hope desperately they’ll ask me questions—and then squirm when they do. Then the thing comes out in print and I’m mad at everybody—including me.

The idea of writing about myself is just as bad. But I just thought of a trick on myself. I’m going to write about Brian Donlevy, me, the actor, as his best friend and severest critic.

You take a look at the Donlevy phiz and you wonder how he ever made a dime posing for collar ads. Yet he did—the rest of the models must have been on strike. He’s not handsome. Rugged, yes, with features that, at their best, are pleasant. And a grin that seems to go down well. At least it’s friendly.

Maybe that’s a cue to the guy. He’s friendly. A lot of people may not completely agree with that evaluation. In fact, a lot of Hollywood people think he’s stand-offish.

That’s because he’s antisocial as far as parties are concerned. But look at it from his angle. He stays away from all parties on purpose. He was scared by a teacup as a boy. Imagine for yourself the boy Donlevy, already sporting those shoulders (the kindest thing that can be said of them being “massive”), feeling awkward and out of place in his Sunday suit. He was asked to balance a teacup on one knee—and a lace doily on the other. He knew he looked foolish. He did.

Parties are a strain and Donlevy is too lazy to search out new strains and stresses. He always thinks things are expected of him from other people at parties. He ought to be amusing—and sparkle for the nice guests and nice hostess. Well, sparkling is not up his alley. So he avoids parties and social functions like a case of chicken pox.

Donlevy is a settled married man. He’s proud of that state. But he spent so many years wandering he clings to the anchor of home life. He revels in it. He’s using it as a sort of bulwark against the adventuring he did before he met Mrs. Donlevy and settled down with her to married bliss. He’s tired of thinking of those adventures. He thinks enough has been said about that period of his life and he’d just as soon forget it these days.

So he’ll tell you about his house in Brentwood at the drop of a makeup box. He’ll bore you with details about the size of the place, the way it’s laid out for farming. He’ll tell you about the Colonial architecture of the house, the way the den is arranged for lolling—when he has time to loll. He’ll boast about how clever Mrs. Donlevy is at furnishing—how she gathers up old pieces and arranges them. And don’t get him started on gardening—he goes on and on about that Victory garden of his—how all the vegetables the family have eaten for two full years come out of the garden; how he does all the work himself; how he rotates the crop for an all-year-round yield. He’ll rave about his corn, the size of his tomatoes and what he’s learned about string beans.

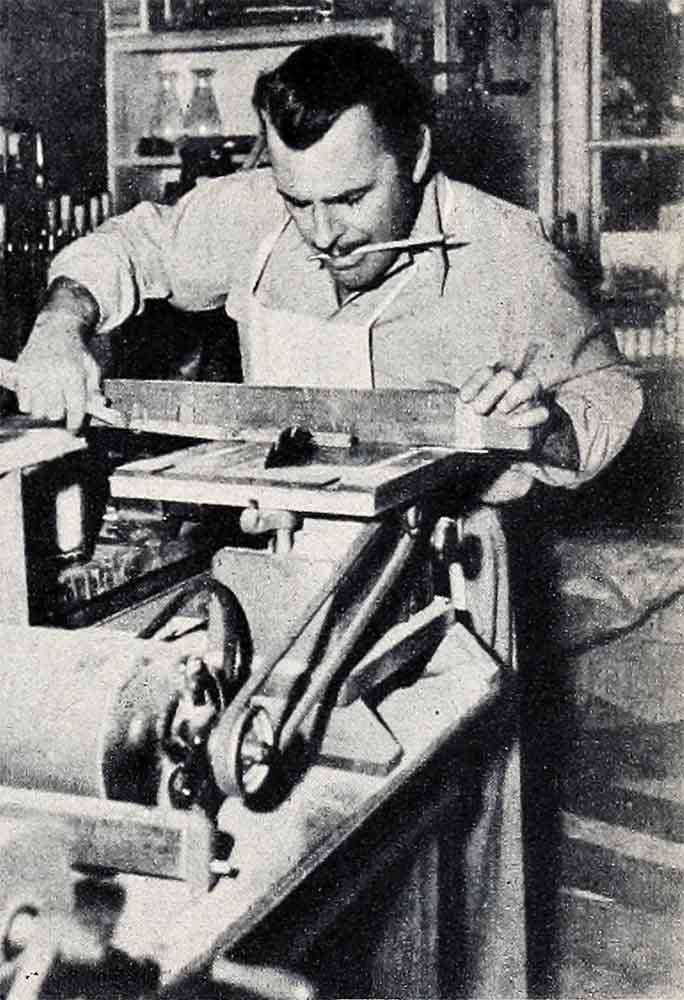

He’s just as unbalanced about carpentry. He’ll take you out and show you his woodworking shop—which he built himself. Then he’ll show you the sheds he’s built, the chickencoops and with that comes a short lecture on hens and the number of eggs they deliver each day.

The best he can say of himself is that he loves to “putter” day in and day out.

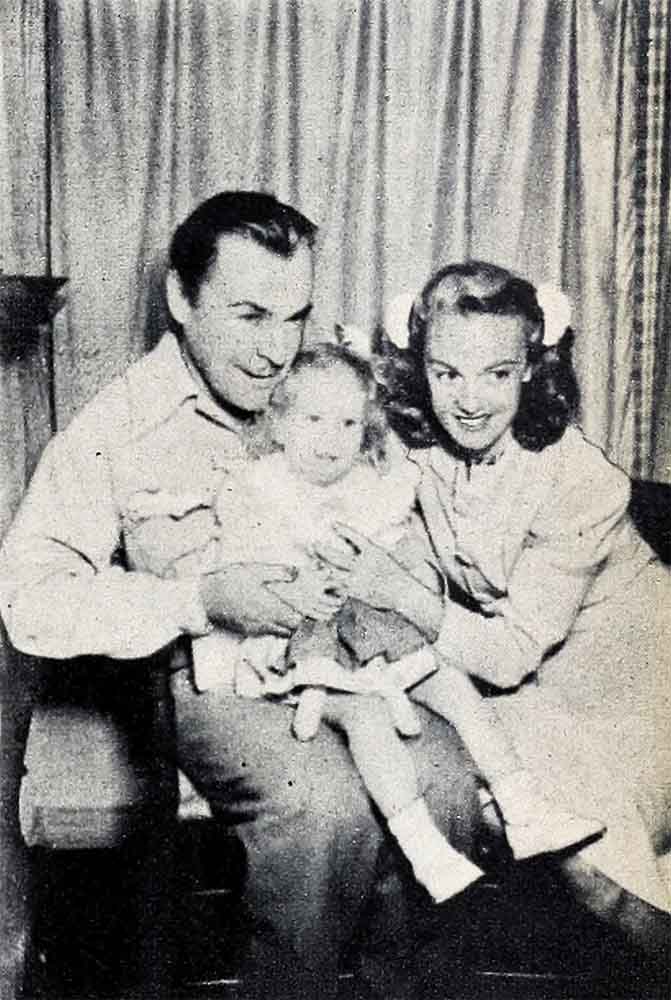

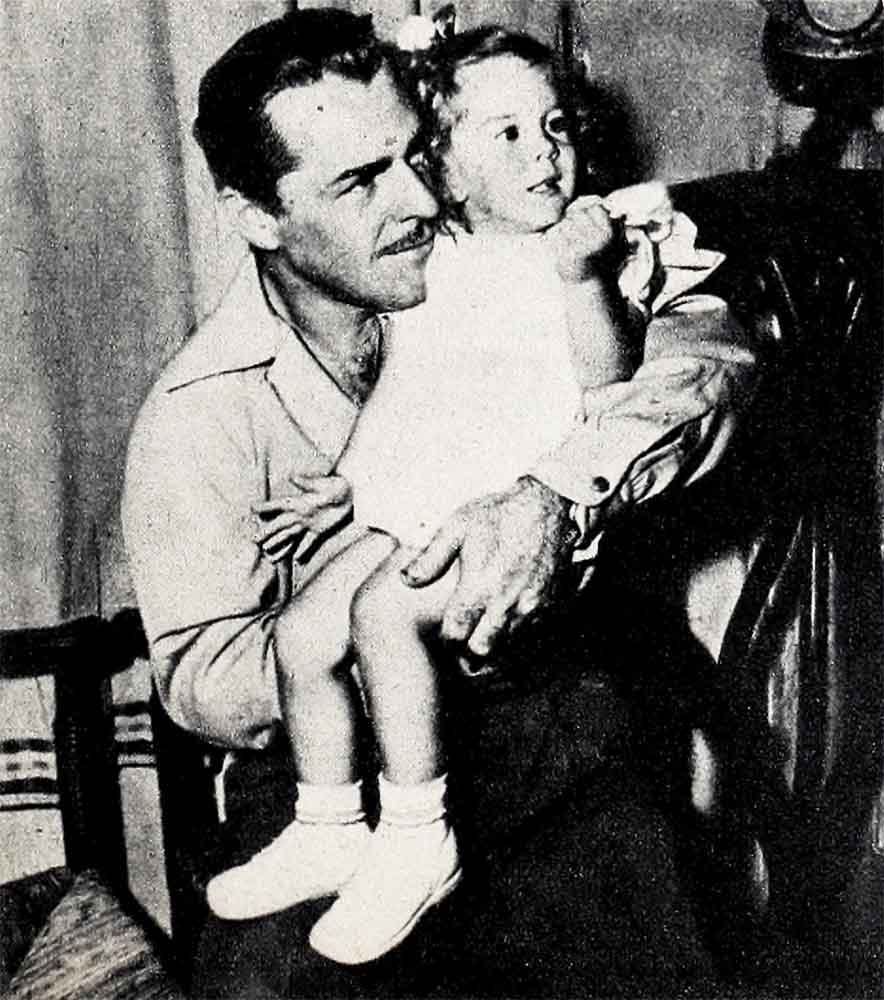

If you’re in a hurry to get away, don’t let him get on the subject of Judith Ann. You’ve never seen a man so nuts about his baby—her curly hair, that smile of hers and the way she’s learning to gurgle so you’d swear she was talking.

More than anything, he wants some sisters and brothers for Judith Ann. At least a brother. He’s got it all planned—how he’d teach him to swim and play games and go out for sports, and the long walks they’d take together and the trips.

No son he’d have would be a pantywaist. He’d be just like his father—and like the same things. He’d want to go with Donlevy to the mine, whenever he could get away from studio work. That’s what Donlevy does now. He piles himself into his two-ton truck and drives for six and a half hours up to the hills over the Mojave desert to the mine he bought.

It’s a tungsten mine, and essential to the war effort. Donlevy works with Prout, the manager, while he’s sharing the camp life, the tents of the mine workers. He never hunts, unless they run out of food and need more—because he never did like the idea of just killing for sport’s sake.

Donlevy’s not sure he would want his son to follow his father’s footsteps into acting as a profession. But Donlevy likes acting, particularly nowadays when he’s got out of the old gangster roles and is really playing the sort of parts he likes—he-man roles, rough, tough and realistic. No glamour parts for him but characters who pack a wallop, who can take it or give it. Those are the kind he’s getting to play now all the time.

Donlevy’s a simple guy. He likes his food and plenty of sleep. You won’t find him night-clubbing. He found Mrs. Donlevy at a night club, fell in love with her while she was singing, married her after what has been called “a whirlwind courtship.” It was long enough to prove to Mrs. Donlevy that he loved her, so what does the length of wooing time matter?

He never skips breakast. That meal is the full treatment—fruit, cereal, toast, eggs and, when you can get it, bacon. He likes a good lunch, too, when he’s not at the studio. There his regime changes. He has his lunch—milk, scrambled eggs and toast—sent to his dressing room. After eating he naps a half hour. (He can sleep any time he sets his head down.)

For dinner, a full meal is his choice. And best of all he likes thick steaks, rare, and spinach.

If you want to find a guy who believes in luck, take Donlevy. He knows how much the breaks are responsible for most careers. They’ve certainly helped him along. He’ll never forget how down and out he was, scraping the bottom of his pocketbook and with just his return ticket to New York, when a break kept him in Hollywood and started him off there.

On his list of people to look up was one name left. His train to New York would leave in a few hours. He played a hunch and looked up a man. It was the casting director at Goldwyn’s—and he took one look at Donlevy and gave him a part in a picture, his first. Donlevy stayed in Hollywood. And Broadway hasn’t seen him since, for which he’s a bit sorry, as Broadway had been very kind to him—after he passed the usual starvation period.

Yes, he believes in luck, but he can’t stand the kind of people who rush off to fortunetellers.

He’s got other definite ideas about people. He doesn’t like phonies of any variety. But most of all, he hates the kind of people who boast about their positions, their abilities and the money they make. He hates the kind who tell you what they paid for this, how much that cost.

The first thing he notices about women is grooming. Next, their faces; third, their shoes. But he’s seen too many glamour girls to be impressed by beauty. “Pretty is as pretty does” seems sound logic to him. He looks for character—and likes intelligence in the fair sex. And he thinks it’s amazing how Mrs. Donlevy combines all three.

Now for the severest-critic part. He’s got the sort of temper of which he disapproves. Instead of a good, healthy outburst and some furniture breaking and then the storm is over, he has the slow-burning sort of temper. He holds it in and carries a grouch. But he’d much rather throw a chair and get it right out of his system.

Otherwise, he’s got a fairly calm disposition. Mrs. Donlevy says he’s too easygoing. She calls him “a sucker for a soft touch and a hard-luck story.” She’s not quite fair about that. Anyone who had the lean pickings Donlevy had, for the length of time he had them, knows about hard luck. Anyway people are good—most of them, he still thinks—and what if you do guess wrong once in every hundred? The average bears you out. Maybe it’s self-indulgence but it’s really a good investment in people.

His worst habit, next to that smoldering temper, is that of lapsing into long silences in groups of people. His mind wanders off and he just forgets where he is. But it’s lousy company manners—as anyone will tell you.

Nowadays, he seldom gets inside a night spot. He’d rather sit around jawing with a few friends and turn in early.

And he’s got one extravagance. Maybe it stems from the time he only had one shirt to his name. He likes buying clothes. His taste is loud, too. He loves jackets of bright colors, noisy plaids. His slacks he’ll take plain but he doesn’t care for neckties and prefers bright turtle-neck sweaters to shirts any day.

He has one hopeless ambition. At least, it hasn’t borne any fruit to date. He wants to be a writer. At school he wrote poetry and had to learn to fight to prove he wasn’t a sissy. Now he writes short stories—which publishers ignore. He’s even tried writing screenplays, which some of the best producers have scorned with a mighty scorn!

And when Donlevy gets mad at Donlevy and wants to give him the devil, he calls Donlevy “Waldo”—it’s his middle name and he’s ashamed of it!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1945