The Charlton Heston Affair

“That story you’re writing about Charlton Heston’s happy marriage—maybe you better hold off on it for a while,” my wife said sweetly across the breakfast table. “Why?” I asked, taking a sip of coffee. “Well, it says here”—my wife pointed with a butter knife at a Hollywood gossip column in a newspaper—“that there’s trouble, ‘big trouble,’ between Charlton and Lydia, and the item hints that there’s ‘another woman’ involved.”

I reached over and grabbed the paper and read the column for myself.

“What do you think?” my wife asked after I’d finished.

“Phooey.” I jumped up from the table and hurried into my room. In a few seconds I was back, carrying some evidence I thought would disprove the item.

“Listen,” I yelled, thumbing through my Heston interview notes, “and tell me if this sounds like the kind of thing a guy would say when he’s about to split up with his wife.

“Here, listen to this. It’s a direct quote from Charlton himself: ‘When you go into marriage, you undertake the most intimate and interdependent human relationship. To come to know someone well enough takes time—you must have enough love to want to do it and enough maturity to be able to do it. Lydia and I had the love to begin with, and we’ve developed the maturity along the way, and as for time . . . all I can say is we’ve been married happily for seventeen years.’

“That’s what Charlton said to me,” I said. “And I remember that at this point in the interview he put his hand on Lydia’s, not hammily, but easily and naturally.”

My wife said nothing for a minute. Finally. as she poured me another cup of coffee, she asked softly, “But how about that reference to ‘another woman’? Charlton Heston is very attractive and . . .”

“. . . and nothing,” I broke in. “Look, I’ve got the answer to that, too. Or rather, Charlton’s got the answer to that. Here, here it is, something he said to a Photoplay writer: ‘I suppose there are some people who think Lydia and I are old-fashioned . . . because we believe in the sanctity of marriage. . . . Perhaps I’m puritanical, but I can’t agree with the conduct of European husbands who boast that a flirtation—even an affair—with another woman is perfectly all right as long as their wives never find out. . . .”

“I happen to like my marriage”

“ ‘I’ve been in love with Lydia since I was seventeen, and the reason I’ve never cheated and never wanted to is that I happen to like my marriage. Nothing would be worth jeopardizing it. I know, too, that if I were unfaithful it would destroy everything I believe in. And, besides, who wants to land on the front pages of every newspaper in the country and wreck his career?’

“Furthermore,” I said, “in my notes I’ve got the answer—again from Charlton—to this ‘apartness’ problem: ‘Often when I’m away from Lydia on public relations junkets or brief location trips, I get a clearer idea than most men what it is like to be alone. No matter who I go out to dinner with or play tennis with, I feel alone. It is possible for me to be alone when I’m in the middle of a crowded room. Being away from my wife is really pointless.

“ ‘It’s not that I depend on her. It’s not that I lean on her. It’s just . . . just I’m a part of something else, of someone else. Of Lydia.’ ”

After this my wife was quiet for a longer time. At last she said, “The columnist must be wrong.”

A little while later I sat in my own room before the typewriter. I shuffled my notes, put a blank sheet in the typewriter and pecked out, in my inimitable two-finger style, “The Charlton Heston Story.”

Two hours later. all I had on the page was that title. It just wouldn’t go. Could the columnist be right? Was there trouble between Lydia and Charlton and might there be “another woman”?

A couple of times during the afternoon I started to put through a call to Lydia in California, but I didn’t complete any. What could I ask? “Is it true that your husband is running around with another woman?” What could she say if it were true? It would be better not to ask at all.

Later, I read the evening papers and there it was again, in the middle of another column—an item stating that all Hollywood was abuzz with the rumor that the Charlton Hestons were breaking up.

In the next few hours, I checked over my interview notes. What had seemed so true, so real, so believable before, now seemed altogether untrue—a mockery!

I even started to doubt the stuff they’d told me about their courtship and the early years of their marriage. About how, when she first dated him at Northwestern, she’d reported to her mother, “I’ve just gone out with the most uncivilized, rude and crude, wildly untidy man on the campus.”

About how their friends, on hearing that Lydia and Charlton had gotten married in Greensboro, North Carolina, on St. Patrick’s Day 1944—just before he, as a member of the Air Corps, was to go overseas to the Aleutians—had all prophesied that the marriage would be “over in three weeks.” Lydia’s father had shaved this even closer by announcing, “I give you two weeks!” But they were so sure. . . .

About how miserable she felt during the three years he was overseas. At our interview she’d told me, “I had a passion for him—beyond logic.” And I’d believed her. Now I questioned even that.

What I did believe, in checking my notes, was what they had told me about their differences in taste and temperament. Oh, sure, they had related these things to prove how time, patience and love can enable people to work out their problems and adjust to each other. But I now saw their differences as proof of their incompatibility.

They’d admitted it themselves. Charlton was prompt and Lydia was tardy. And she was orderly and he was disorderly.

Then there was the business about their fights. Of course, they’d put their disagreements in the best light. They’d talked about the “need to communicate” and agreed it was best to “get everything out in the open, quarrel and get it over with,” but now I wondered if this had all been window-dressing. The important fact was not in their “maturity and adjustment to each other,” as they had claimed, but the fact that they did fight.

That incident about their quarrel when they lived in a cold-water, walk-up flat in New York during the first years of their marriage, for instance. When they’d told me about it, they put it forward as an example of the way they used to fight before they learned “not to go to sleep before working out a disagreement.” Now I saw it in its true light: as an example of the way they fought then and must be fighting even now—years later.

They’d had a violent quarrel (during the interview they insisted they couldn’t recall what the squabble was about, but now I questioned that, too), and Charlton had stomped out of the apartment. Lydia had gone up and down the Street looking for him, without any luck, Finally, from a pay phone, she’d called a friend. “My husband’s left me,” she sobbed.

Her friend’s husband and another man rushed right over, even though it was after three in the morning. The two men went out and combed the waterfront. (Before stalking out, Charlton had dramatically shouted something about going for a walk along the docks.) Two hours later they were back. No Charlton.

Lydia was crying her eyes out, insisting she’d never see her husband again. The two men were trying to comfort her, and doing a poor job of it. Suddenly, the door opened and Charlton walked in.

“Where have you been?” Lydia cried, throwing herself into his arms.

“Up on the roof,” Charlton confessed sheepishly, not able to meet the eyes of the two other men. “I never left the house.”

Tender? Funny? Phooey. Just proves that they fight.

Finally, I put a call through to the Coast. The Los Angeles operator told me that Mr. Heston was out of the country, but asked if I wanted to speak to someone else.

And everyone I called added fuel to the fire. Yes, there was “another woman.” No, there was no chance of a reconciliation. Yes, all the items were true, and there was much more that wasn’t being printed. No, Charlton and Lydia weren’t talking to the press.

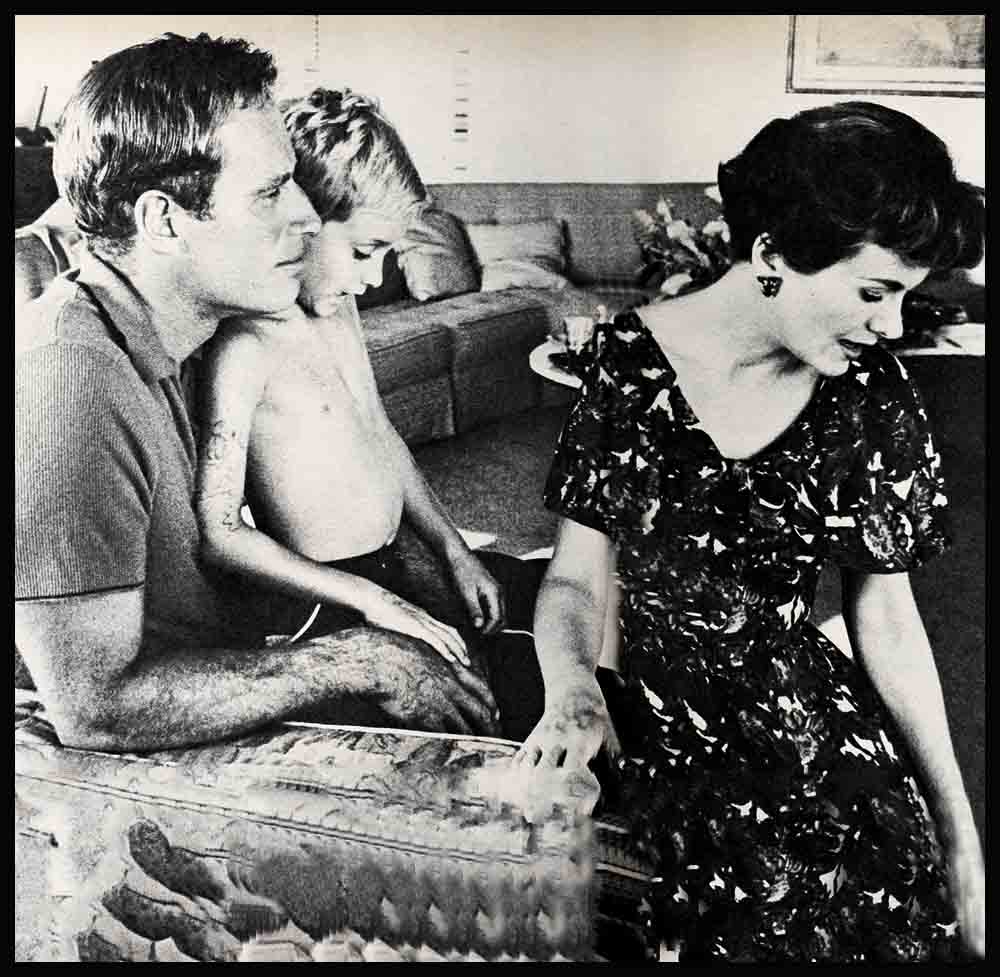

The one thing that still didn’t make sense, however, was Fray, their six-year-old son. It had been nothing specific that they’d said; it had been everything they’d said. Both Lydia and Charlton seemed crazy about the boy (I was sure that their feeling about him was genuine), and they’d indicated that their love for each other was deeper and more secure because of him. How could I square that with the items columnists and Hollywood “insiders” were telling me about their break-up?

Lydia, for instance, had told me about Fray’s tonsil operation, and as she recreated the scene, little drops of moisture stood out on Charlton’s forehead and he again reached for his wife’s hand and didn’t let it go until she had finished talking about it.

They’d done everything possible to make the ordeal easy for Fray. They’d told him all about what would happen, minimizing the danger and emphasizing the adventure and novelty. They’d read “So You’re Going to the Hospital” books to him. They’d even gone so far as to act out the operation with him: Lydia was the nurse who pushed the wheeling-table down the hail to the operating room; Charlton was the doctor who joked with the little patient and casually slipped the make-believe ether cone over the boy’s face.

Everything had gone fine in the hospital itself. They’d walked by his side as he was wheeled along the corridor to the elevator that was to take him to surgery. At the last moment, Fray’s little face—beneath a white surgical cap that was too big for him—lost its set, “grave” look. And he pleaded, “Mommy, can you tell me a quick cowboy story?”

The operation was successful, and they told him lots of cowboy stories after he came out of the ether.

And now, if the rumors were true, they’d have to tell Fray a much more difficult story—they’d have to tell him they were separating.

It just didn’t make sense. Charlton had once said, “You live over again through your son. There is also quite a challenge in trying to be the kind of man your son thinks you are. It’s easier to let anyone else in the world down than it is to disappoint your son.” But now he was about to do just that—disappoint his only son.

Suddenly, unexpectedly, there was something new in the Heston affair—it was in Ed Sullivan’s column in The New York Daily News—something new, and screwy and unbelievable. “The Charlton Hestons,” the item said, “adopted a baby, Polly Ann.”

Back to the telephone. More calls to the Coast. More confusion.

Yes, said my informants, they’d seen Sullivan’s item. No, they couldn’t understand it. The Hestons were splitting up. The adoption news was obviously a smoke screen. Lydia and Charlton still weren’t talking to the press.

Must be a fake item, I agreed. No people in their right minds would adopt a child at the same time they’re working out a divorce agreement.

But a few days later the adoption story popped up again, this time in Louella Parsons’ column in The New York Journal-American.

Crazy! Again I tried to telephone Charlton directly. Again he was out of the country, in Italy making “The Pigeon That Took Rome.” I’d just have to wait until he got back.

So in the weeks that followed I had to try to solve the unsolvable mystery of why two people in the process of breaking up would adopt a child.

Finally the solution came, and it was as involved as the final chapter of a mystery novel when the author ties up all the loose ends together, unravels the clues and puts his finger on the real murderer. Except that this attempted murder was committed by gossip—an unusual weapon. All the other ingredients were up to par. For the victims, Charlton and Lydia and their marriage were almost done in—as is often true in mystery stories—by a “friend of the family.”

Chapter One: A “friend” phones Lydia while Charlton’s in Europe and asks whether she’s seen the item in Sheilah Graham’s column about Charlton and his script girl.

Chapter Two: Distraught and disturbed. but without checking the item. Lydia calls Charlton’s press agent and says that she’s just learned that Columnist Graham claims that her husband and his script girl are having an affair. The news comes as a shocker to the press agent too.

Chapter Three: The press agent and Lydia make separate calls to Charlton in Rome, asking if the item is true. To both, Charlton, enraged, replies, “Absolutely not!” And then, “How could she (Sheilah Graham) do such a thing to me?”

Chapter Four: Charlton, still furious, places a call to Columnist Graham. She’s in London where it’s now 5 A.M. “You have been responsible for keeping me awake all night,” Charlton tells her, “and now I am awakening you.”

Chapter Five: In Graham’s words, “It was dark, I was exhausted, and I broke a glass reaching for the phone. I spluttered, ‘What are you talking about?’ and dropped the phone. Then I, too, was raging and wide awake.” Sheilah re-reads item. Finds that it stated that the script girl had left Charlton’s picture in Rome and flew to Hollywood for a few days to work on “One, Two, Three” and that she would then fly back to Italy to continue work on Heston’s film, item concluded: “How dedicated can you be?”

Chapter Six: Five-thirty A.M. Sheilah calls back Charlton and reads column to him. Item obviously referred to script girl’s dedication to “One, Two Three” and had nothing at all to do with Charlton. “There’s nothing wrong with that,” Charlton says. “I’m glad you called.” Sheilah hangs up.

Chapter Seven: Lydia arrives in Rome. Whole town buzzing about Charlton’s “affair” with the script girl. Charlton talks. Lydia listens. Two days go by. Finally. everything straightened out. No more misunderstandings, no more heartaches and no more gossip. Only apologies.

Chapter Eight: Charlton’s press agent sends cable to Sheilah, apologizing for himself and for the actor. Lydia sends Sheilah letter of apology. Charlton apologizes to Sheilah in person.

Chapter Nine: Here and now I want to apologize too—to Charlton, Lydia, Fray and Polly Ann. My wife says, “Me, too.” The End—Today Charlton has someone else to belong to—baby Polly Ann. “She is so beautiful, and we’re just crazy about her,” he says.

Lydia is ecstatic, and Fray . . . Well, Fray was pretty jealous at first of his new sister, but then one day he walked over to her crib, patted her gently and said, “This is the first time I have had any mercy on her.”

Which is a boy’s way of saying everything’s okay at the Heston house.

—JIM HOFFMAN

Charlton is in Allied Artists’ “EI Cid” and “The Pigeon That Took Rome” for Par.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1962