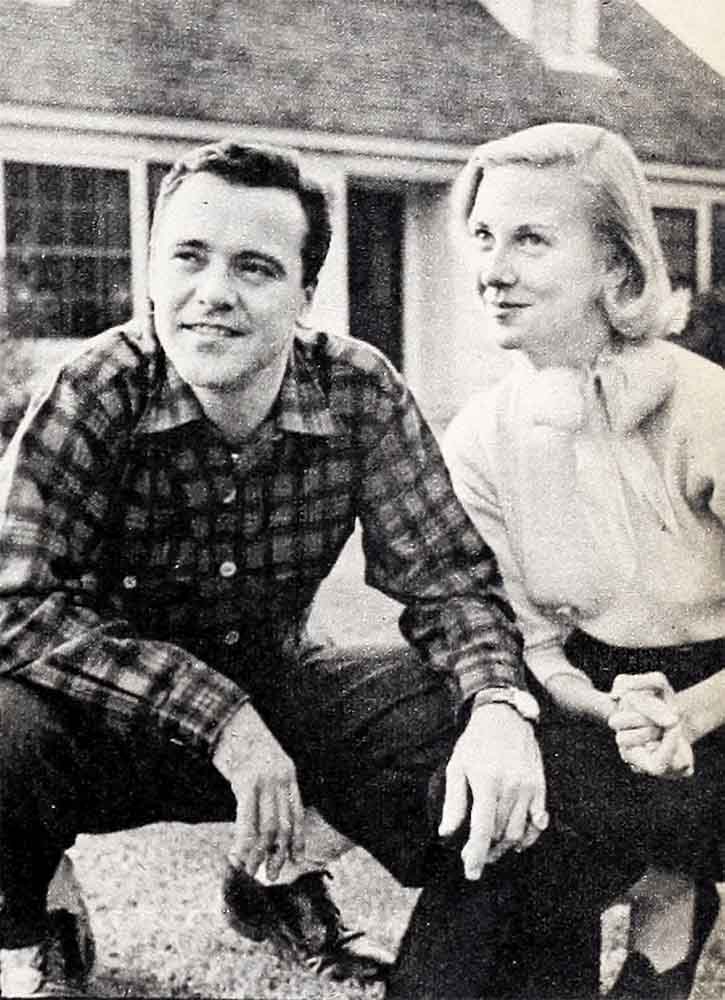

Whatever Happened To That Nice Couple?

Frequently, these evenings in Hollywood, you will see Jack Lemmon and starlet Mona Knox at a small cafe called the Bantam Cock. If you are a quick conclusion-jumper, you might think this a romance. Jack is in the process of being divorced by his lovely blonde wife, Cynthia, and Mona is pretty, witty and unencumbered.

However, if you watch Jack with Mona, or with any of the other girls he has dated since his separation, you will soon realize there is something awry about the romantic picture. For while Christopher Boyd John Uhler Lemmon III definitely arrives at a cafe with his girl, and definitely leaves with her, most of the time while he’s at a cafe he is away from her. Generally he spends the entire evening seated at the piano.

AUDIO BOOK

With his debonair charm, his comic young face aglow as he crosses the restaurant, Jack waves a quick and humorous hand to move the professional piano player away from the keyboard. Then he takes over, for a brief moment looking exactly like the slap-happy Ensign Pulver of “Mr. Roberts.” Already the onlookers are laughing appreciatively.

Jack grins at his audience. But as they turn back to their drinks and their dinners, his face sobers and saddens. He goes into a swing number, softly; one called ‘I’m With You.” Then he modulates into a sentimental tune called “Now.” These are songs of his own composition, which he wrote several years ago for a musical which was never produced.

As he sits at the piano strumming, he seems to forget the time, the place and, most particularly, the girl.

At these moments, he is not the funny Ensign Pulver. Nor is he the zany young fellow he was a couple of years back at a certain Compo luncheon.

Compo is an inner-Hollywood affair, which each year nominates the most promising new players. At that luncheon, Jack had been called on stage with Tab Hunter and George Nader, two of the other winners. There the three of them stood, when Rita Moreno was called forth. Tab and George gave her friendly smiles as she walked toward them, but Jack was visibly transfixed, his big eyes taking in every delicious curve of the Moreno figure. Naturally, Rita got it quickly and wiggled exactly the right amount as she approached, whereupon a low wolf whistle escaped Jack. This moan of pure masculinity brought down the house.

. . . on the happy years with Cynthia?

No, these nights around Hollywood, Jack rarely reveals this dashing side of his nature. But neither is he the rather tense young man he was last spring, when he and his wife first broke up. Then, the worry evident in his voice, he said that he “hoped it would be all right.” Before that, he had been the doting young father, telling stories about his small son, Chris. He’d stop you on the Street or at a party to tell you such sweetly innocent things as how Chris had stood at the window and addressed the sky, saying, “Moon too high for boy. Come down, come down.”

But these evenings, since Cynthia has gone ahead with her divorce action, you can see that Jack is fluctuating among many moods. He now has a swank bachelor house in the most exclusive section of Bel Air. He drives a dashing red Thunderbird. And he is casual—much too carefully casual—as he explains that, though divorced, he and Cynnie, as he calls her, are still such good friends that they baby-sit for one another. Cynnie for him when he has a date with another girl, and he for Cynnie when she has a date with another man.

It was last summer, while Jack was making “Fire Down Below” on the island of Tobago, that I first comprehended what was going on—that Jack Lemmon was probably acting as much for himself as he was for audiences, trying to persuade himself that he was happier than he is, that he could do anything, and hadn’t a care in the world.

Superficially, it was great. Career-wise, he was hot as a tin pistol. His contract with Columbia is one of the best. It even permits him to make outside pictures like “Mr. Roberts” and collect his own salary on them. It would have been perfect—if P only, just a few weeks before his Tobago location, he and Cynthia hadn’t separated. This was a real Hollywood shocker, because the Lemmons had seemed such an ideal young couple—popular, well-off, well-bred, intelligent. Their future looked platinum-plated, until they agreed to part and neither of them would tell why.

Of course there had been some buzz around Hollywood when, at the exclusive Robert Mitchum dinner-dance last spring, Jack, who had come stag, had been seen dancing almost every dance with June Allyson, his co-star in “You Can’t Run Away from It.” But nobody took hat seriously, since Jack and Dick Powell and June were obviously all such good friends. Furthermore, both Cynthia and Jack said they had no immediate plans for divorce. It was, they said, merely a separation.

By mid-summer, however, when Jack was in Tobago, the rumors that he was interested in beautiful Rita Hayworth were being flashed everywhere. These, I am here to tell you, were just more quick conclusion-jumping. I know, because I went down there, stayed for a long, dreamy week with the “Fire Down Below” company and saw Rita and Jack day after day and evening after evening.

There’s no other woman. Rumors linking him with Rita Hayworth on location were without foundation

As a setting for romance Tobago is a dream. The luxury hotel where the company was staying is located on a little hill, deep in cocoanut palms. In one direction stretches the jade-green Caribbean. In the other is the sapphire blue Atlantic. The temperature is a constant 80 degrees, day and night, cooled by scented breezes. Strange, wild birds sing the whole night long.

The “Fire” company was a very congenial one. Evenings, after the hard day’s shooting far out at sea, they would all gather together on the vast porch of the hotel, for laughter, talk and cocktails. Rita, vividly beautiful, her red hair flying about her shoulders, would be there with co-star Bob Mitchum, director Bob Parrish, producer Cubby Broccoli and Cubby’s wife, as well as the character actors and the crew. Everyone was there, in fact, but Jack.

Jack would be in the hotel parlor, at the piano. Actually this kept him within sight and sound of the others, since the hotel has big open arches in place of the usual windows and doors. all the same, while the rest of the troupe were laughing and chatting together, Jack Lemmon would be alone, playing those nostalgic compositions of his.

On a tropical island under a tropical moon, with one of the most beautiful women in the world present, Jack Lemmon stayed alone. If that’s not carrying a torch a mile high, you name it.

But Jack wouldn’t admit the torch then and he won’t admit it now. In many ways this comic fellow is unaccountably moody, quixotically stubborn, and unpredictable. It is like his growing up a rich boy and then, when he decided to become an actor, nearly starving himself to death while he lived in the cheapest of New York’s miserable cold-water flats. Then there was his taking Cynthia to the Automat for dinner on their first date together—the Automat is practically New York’s cheapest eating place—-when it turned out that he could afford even that only because he had gone without lunch. And there was the ridiculous way he and Cynnie, when they arrived in California, moved into such an enormous house that they couldn’t afford any furniture for it or any servants.

Mixed up in all this, in a way expressing it all, is Jack’s piano playing. He said to me, “This is just something with me. Unless I can get to hitting the keys at least once every day I become restless and depressed for no good reason.” On screen he’s a very glib talker. Off screen he is not. Speaking of his music, he had to pause. Then he added, “I write—or I try to write—a song nearly every day. I can’t put into words how much I want to write a hit tune. Someday I will.”

But just why he wants this he doesn’t seem to know. Another of his complex sides rises when it comes to his acting. He is a superb comedian, but he hates to be known as one. He wants to be known as a serious Actor, with a Capital A. That’s why he was so delighted about his role in “Fire Down Below”; it was serious in every frame. And he was even more delighted about a TV show he did in which he played Abraham Lincoln.

Even when he talks about his war service—and he does it amusingly—he is actually emphasizing this quality of his nature. In this case, he was quite innocently put into a false position and emerged from it with what looked like heroism and brilliance. He feels he appeared to be something which actually he was not.

Jack, who grew up in Brookline, Massachusetts, the very, very fashionable suburb of Boston, and whose father was and is the vice-president of the Doughnut Corporation of America, went to Harvard for his Naval training. He emerged an ensign and was put into Communications and sent to sea almost at once. Only he hadn’t had any training in Communications. He couldn’t have read a signal flag if it had come up and clunked him.

A mere ensign, as every mere ensign knows, doesn’t complain of such things to his superiors. Ensign Lemmon did not. And thus, one day, he got a fast call from the bridge to read a message which an approaching vessel was flashing. Desperately Mr. Lemmon looked at the fluttering signals. Desperately he gambled.

“Sir,” he said, “the vessel wishes right of way.” By the grace of heaven, that was just what the other ship wanted. By the grace of heaven, each ship moved just in time to avoid a collision. Later, the commander said, “Well done, Mr. Lemmon.” Shortly thereafter Mr. Lemmon was transferred to a shore base and never was a man happier.

In actuality, however, this was Jack’s luck holding again—and his holding his tongue about it was typical, too. So was his nearly starving when he got out of service and came to New York to try to be an actor. He could perfectly well have borrowed the money from his rich father or his adoring mother. He stuck it out on his own, however.

Cynthia was the same type of girl. Born Cynthia Stone, she, too, came from folks blessed with much more than the average possessions. Yet she seems always to have been willing to share the wild kind of thrift which Jack persisted in, originally in New York, and later when they both came to Hollywood. They first met in 1947, were married in 1950 and in 1954 Chris was born. In between there were more than 500 TV shows for Jack. There were almost that many for Cynnie. She was, in fact, more important in radio and TV circles than Jack, and she taught him many a trick about using his voice.

Back here, in the days of their courtship and the first years of their marriage, they had everything in common—ambition, laughter, hard work, and their self-imposed poverty. They could dine together because Jack had a side job as checker for a restaurant chain, and had to go from cafe to cafe to test out the food. once they were married, they costarred in and produced three different TV series. They were convinced nothing would ever part them.

In 1951, after a series of flop plays, Jack was signed by Columbia for Judy Holliday’s picture, “Phffft.” Joyously he and Cynnie came West, got the big house, in which for a long time they had virtually no furniture, did all their own work, including the housework, cooking and gardening, and waited for the baby.

But the closeness they had shared began to evaporate, at first slightly, then more and more. Cynnie was home, too often alone. Jack was at the studio or somewhere else, recording or whatever, and ı the whispers were that he wasn’t always alone. Last April the blow-up came.

Jack said, very dignified, “We just haven’t been able to get along together and we thought this would be best for our child. Neither of us is considering a divorce, but there is no thought of any reconciliation. There is no other man or other woman.”

That’s what the man said—in April. But in June, in Tobago, he was saying he “hoped everything would be all right.” In October, Cynnie filed for her divorce, charging incompatibility, and in the beginning of the winter they were talking about what good friends they were, with both of them being most careful not to say one word that might hurt the other.

Which is really a hopeful sign. For in this they are like the Jeff Chandlers, who separated, and reconciled, and separated again and were to have it “all over”—except that they couldn’t stop thinking of one another’s feelings, or about their i children.

Under his natural charm, beneath the drive of his intense ambition, it’s plain that Jack Lemmon is not happy. Just as Jeff Chandler wasn’t.

Jeff went back and Marge Chandler forgot past hurts for the sake of a future happiness. I hope it works out the same way for Jack Lemmon and his Cynnie and I their Chris.

THE END

SEE: Jack Lemmon in Columbia’s “Fire Down Below.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1957

AUDIO BOOK