She Was A Prisoner Of Fear—June Allyson

It is not especially difficult to drive a car off the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lot. It is, in fact, much easier than to drive one on to it. But for June Allyson, one day not too many months ago, this simple act was a matter for genuine, nerve-shattering terror.

For she was leaving, after eleven years, the only picture home she had ever known. In a state of fearful panic, she had decided to free-lance and declined to sign a new contract. Weeping from both fright and sorrow, on her last day she made the studio rounds, saying goodbye to persons she was convinced were the only professional friends she had or could expect to have again in her lifetime. Then, in a panic, she drove out the east gate, past the Irving Thalberg Building into the ugly golden smudge of Culver City.

Sounds absurd? Then let June Allyson tell you.

“I didn’t think anyone would hire me. And please don’t laugh. I’m not hamming or fishing for a kind word. I’d never worked anywhere but Metro. I didn’t know any other studio people. Maybe they wouldn’t like me. I didn’t think they would. It seemed to me there were just Richard and the children left, no other security. Wasn’t that a horrible way to feel? I’m ashamed in a way. I’m so easily frightened. I guess I’ll always be frightened. But it’s so much better now. I’ve done what I was always scared to do and it has worked—knock wood—so far anyway. I found it wasn’t dark out there after all. It was bright daylight.

“Even if I hadn’t been wanted by the other studios, even if not a single one had asked me to work, I wouldn’t regret now what I did. Leaving M-G-M meant something to me. It meant I had the nerve to go out on my own, and that’s led to a lot of other things. It’ll seem silly to you, but I do marketing now. You can laugh this time and I wouldn’t blame you. Isn’t that raw courage? Marketing. But I used to hate it. I was afraid of things, afraid of people, afraid—oh, I don’t know what. It was like wanting to hide your head under a blanket—you know? I guess, really, I was afraid of failure, afraid to try anything because I might fail. That’s terrible. I admit it now. I’d even admit it then, but it didn’t make me braver. And I don’t think it ever once occurred to me that if I was secure in my own little way, I was—well, a prisoner, too. A prisoner of my own fear, or for that matter, my own security. Does that make sense? Before I couldn’t exactly get off the ground. Just hopped around like a chicken. Now, well, I have a sense of freedom. I don’t mean I’m an eagle yet. I’ll never be an eagle. But here I am, without being told to, walking right up to the man and saying: ‘What shelf do you keep the ketchup on?’ Or if it’s a real good day: ‘Would you kindly direct me to the canned meatballs?’ For me, that’s good.”

June Allyson’s confession was made at her home one bleakish Saturday afternoon. There was an open fire, soft lighting effects and an Early American decor that slammed the door on inclemency.

In truth, the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Richard Ewing Powell of West Los Angeles, California, is something of a masterpiece of opulent warmth. It may also be regarded as vaguely symbolic of the onetime state of mind of the lady of the house. It is a reconverted farmhouse that once was the property of John Charles Thomas, the singer, and before him of a wealthy Los Angelean with a great deal of money and the desire for both luxury and retreat in a single package. But this man died less than two months after fulfilling his dream, leaving what he had built for those who sought the same things.

The home is in that section of West Los Angeles called Brentwood, off a canyon road named Mandeville. Most Mandeville homes are in cozy proximity to each other, even those of such notables as Robert Mitchum, Richard Widmark and Ben and Esther Williams Gage. But the Powells’ home cannot be reached so easily. It stands atop the highest residential hill in the area, accessible only after a half mile of twisted climbing driveway, free from encroachment. Call it a retreat, a hideaway, what have you; for the small, nerve-ridden, extremely talented young woman called June Allyson it was a haven from all she did not know.

But now that’s all behind her. June Allyson has gone through a nightmare and a revelation. The result is a sort of personal triumph that June Allyson has managed herself. For she alone had to open the door; the door whose very knob she was afraid for so many years even to touch. She opened it and found on the other side not monsters and lonely winds of night but sunshine and freedom.

When June left M-G-M something bright and familiar had been turned aside to be replaced by—what? She found it almost impossible to think about it and, when she did, she was scared so badly hat she came close to crawling under the bed for keeps.

“And thank heaven I didn’t!” she confided. “This much I’ve learned: We all have to see our own private haunt for what it is. And we must go out to meet it—alone. That’s more than half the battle. And until we’ve won that battle, we’re never whole, never mature. I can’t honestly say any one thing is the most wonderful that’s ever happened to me because there have been many wonderful things. But right now, I’d be inclined to put this new feeling of confidence right behind Richard and the children on my all-time good luck list. I just can’t tell you.”

In the firelight, her face seemed to sadden for a moment. Firelight, though, is a tricky business, and it didn’t have to mean anything.

“Maybe,” she said, “I’ll never be wholly what you’d call a New Woman. I’ll always need Richard and the children and—and here, what this home represents. These safe, warm walls I know so well. There’ll be some fright as long as I live because that’s the way I am. But the one big fright, that I couldn’t step out of protection and go it facing the wind—that’s over. If I never make another picture as long as I live, that’s over. I can’t help sounding square about this, but it’s like being born again and seeing a thousand things you never knew were there. Now I’m not even sure I was really living before. I was in a cage. Life couldn’t get in to harm me, but I couldn’t get out either. Now I’m out and I love it.”

Nothing is more dangerous than amateur psychoanalysis, but the old June Allyson, the immature one, can be pretty well understood if one goes back to her wretched childhood and her fearfully precarious adolescence. This insecurity left her with the belief that no altitude is high enough, no grip so firm that it cannot be pried loose. She lived in constant terror that somehow she might lose all she had gained and have to start over again.

As a youngster, June lived under New York’s Third Avenue El, on a clanking street of tenements, hock shops and casual bars. And if this were not bad enough, she suffered a near-crippling accident when her spine was injured by a falling tree. Later, at an age young enough to conflict with child labor laws, she was a night-club dancer and still later a musical comedy novice, dancing in the line with a chap named Van Johnson under the direction of another chap named Gene Kelly. Such experiences could have been fun—except that they meant the difference be- tween eating or starving. For June, the struggle from a chorus line to star status and boxoffice darling was a long, hard pull. Which is why June was so grateful to Metro for signing her and giving her an opportunity. It was also the reason why she found it difficult to leave the studio. But June left Metro and the reason was a simple one. She didn’t like the pictures she was doing. It was simple as that—and as unsimple. In her last months there, because of a number of lightweight films that frankly leaned heavily on June’s boxoffice drawing ability, she was most unhappy. On the other hand, her devotion to the studio that gave her her chance and nurtured her to classic stardom was not only sincere but intense. These, coupled with her morbid fear of the outside world, and you have the reason for her severe emotional schism.

Advice—except from Richard—was the worst thing she could have got, but she got it. The new contract was ready for her and Metro was bearing down quite and on words like loyalty. It was a word to which Miss Allyson was tenderly susceptible and this didn’t make her choice any easier. But finally she made it. Her conflict had its aftermath. She broke out in a skin rash, caused by nerves; holed up in Mandeville and became what the Hollywood press calls waspishly uncooperative.

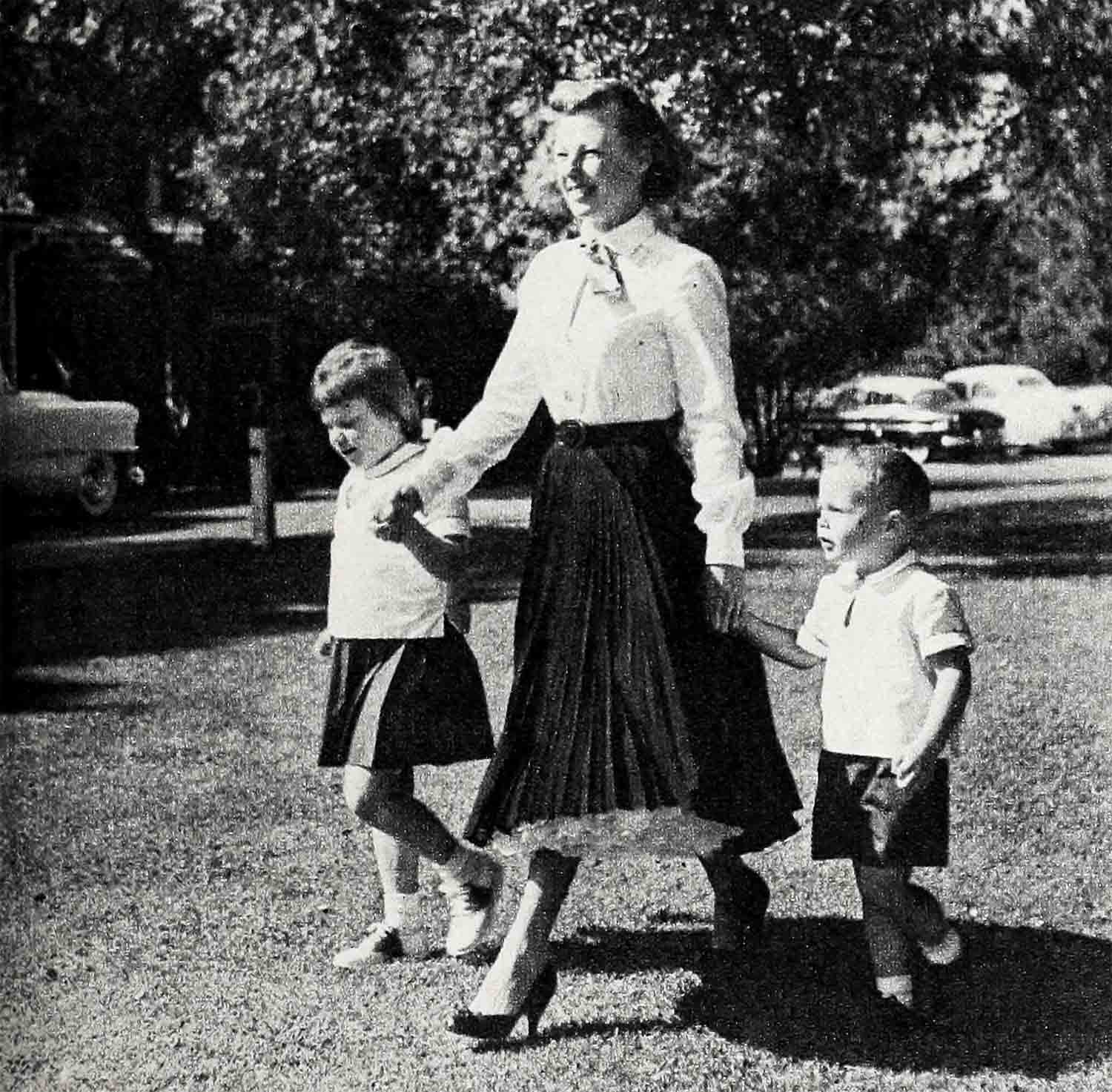

At this time Richard, the children and her home were her bulwarks. Richard had approved her decision. But Richard wasn’t doing the hiring that year and June soon settled on an attitude that no studio in its right mind would give her the back of its head.

Richard, however, was quite an asset. He is as stable as June was, at that time, unsettled. And he is as philosophic about career business as she is single-minded. Always there has been something vaguely paternal in Richard’s approach to June However, for any man over the age of twenty-five not to feel somewhat paternal toward June Allyson would be unusual, since much of her appeal is childlike. She is never cute in the uncomfortable sense of the word. She is merely eager, buoyant, a little like a puppy tugging at a leash with a small wistful face that is probably one of the most expressive in films. Richard’s guidance has always been steady and able. A writer friend of the Powells can remember, for instance, one night when he and his wife were waiting downstairs in the Powell home for June to finish dressing. Richard was ready and the three were talking. Presently a servant came into the room with a very pale, innocuous version of a Scotch and soda.

“I have one, thank you,” said Richard. But this wasn’t for him, the servant explained. This was June’s. June did not, and does not, dabble much with strong tonics and had instructed that Richard taste hers before she drank it. Evidently his was the only trustworthy decision she could rely on—whether or not the highball contained the extra drop that would send her spinning. The degree of this reliance struck the visitors as a trifle amazing.

Yet there is another side to June. On the way into town that evening, a matter of trade gossip arose, some mild criticism Richard had been tapped with in one of the columns. June became ferociously protective. “Nobody can say things like that about Richard!” she exploded. “Nobody has the right to! Richard never hurts anyone! He’s the sweetest person in the world. Aren’t you, Richard?

“How right you are,” said Richard equably. “How do you think I made Eagle Scout?”

That’s about how it is with the Powells—except that maybe these days, June is beginning to show healthy signs of an increased independence.

For on this day on Mandeville, Richard was out hustling a buck somewhere and June was doing her own talking about her newfound freedom. And from the sounds of it, June intends to go right on doing her own talking.

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1955