Good Boy

EDITOR’S NOTE: Here are the three most talked-about young actors in Hollywood today—Murray, Perkins and Presley. Here is what Hollywood and movie audiences think of them. Here is why each of them is destined to start a whole new trend in movie heroes

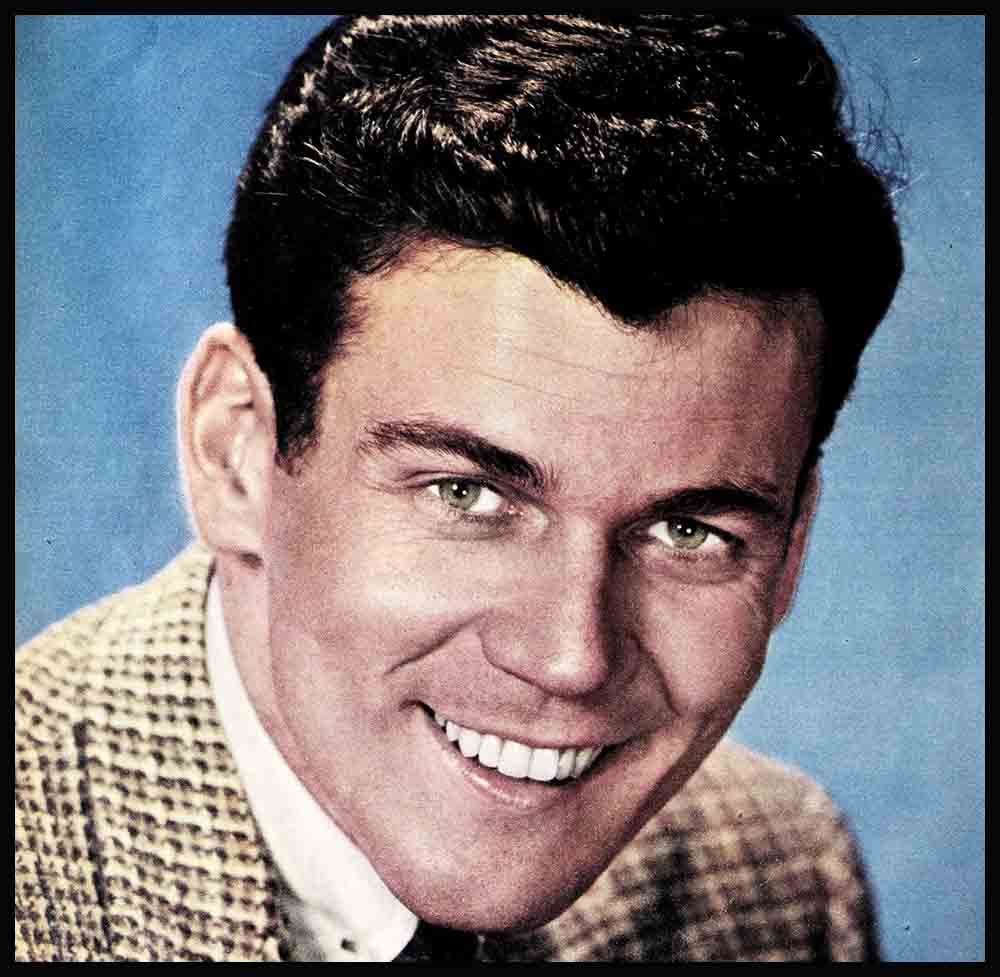

Don Murray comes to the screen and to Hollywood not like a breath, but like a gust of fresh air, a young man full of good spirits, good sense and good cheer. Less than a year after signing with 20th Century-Fox, Don is known in the trade as a “tough interview,” because you can dig all day, talk to anyone who’s ever known him, and you won’t come up with a single, blessed word that’s “gossip,” that isn’t all in Don’s favor. He’s clean-cut, wholesome, deeply religious and seems inevitably slated to play manly but unsophisticated screen roles, such as the one in “Bus Stop” which got his screen career off to such a flying start.

AUDIO BOOK

Don’s interviews also get off to a flying start—and then come to a dead stop—as a result of the first question ever put to him. “You and Marilyn Monroe both studied at the Actors’ Studio,” the interviewers invariably point out, “and after all, landing a plum such as the lead in ‘Bus Stop’ opposite Marilyn is quite a break. Was she at all responsible for getting you that break?”

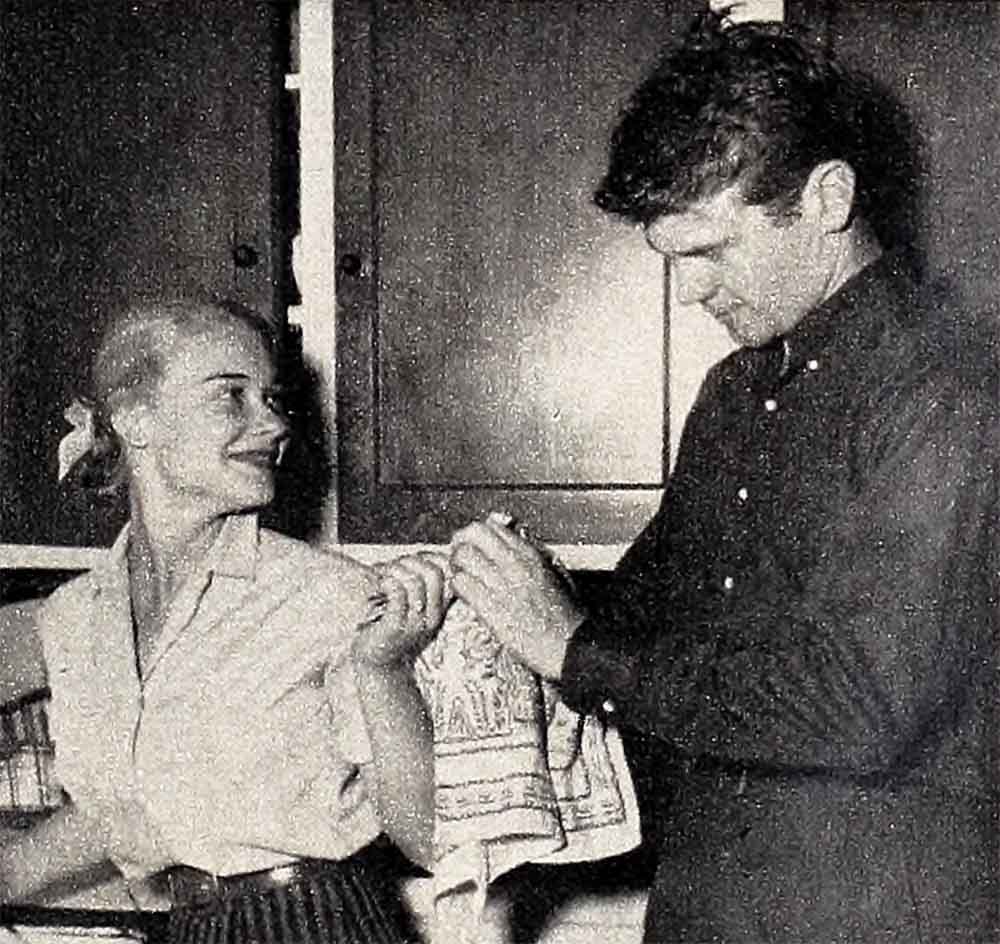

When his latest interviewer asked him that, Don reached for the hand of his lovely young bride, Hope Lange. They smiled at each other, exchanging some silent communication in that universal language of lovers. Don’s smile lingered as he turned back and said, “Heck, no. I didn’t even know Marilyn when I got to Hollywood.”

Then he said, “And now you’re going to ask me what it was like to work with her. That’s always the second question, so I’ll save you the bother of asking it. Working with Marilyn Monroe was great. I think she’s a better actress than most people realize. In fact, she’s a very good actress.” He finished pleasantly, “Now, you just ask anything else you’d like to know and I’ll be glad to tell you.”

He will, too. His life is literally an open book, with no hidden pages marked “not for publication.” He doesn’t drink or smoke, he married the first girl he ever loved and their first child is due to be born next spring. He also frowns on profanity as being mostly a form of mental laziness. But profanity, like swaggering and bullying, is usually just an outer show of toughness to cover an inner weakness. Don can afford to admit his lack of vices because no one would be apt to make the mistake of thinking there is anything weak about him. He’s a rugged, solid, serious six-foot-two of man, and all man. He doesn’t have to prove it, for you know it the minute you meet him.

He’s impulsive, impetuous and impatient. The only exception to this has been his courtship of Hope. He waited five years, talking himself hoarse every time they were together. But Hope, who plays the same role in the film version of “Bus Stop” that she played on the stage, is a practical young woman. She knew the hardships that lay ahead. Like Don, she never doubted that he’d make the grade, but she felt he would have a better chance if he traveled alone at first.

They were married last April, during the filming of “Bus Stop.” The studio gave them a few hours off, and they had a quick civil ceremony that was followed, three months later, by a religious ceremony in New York. Then, before the ink was dry on the marriage certificate, Don was on his way back to California to make “Bachelor Party.” Hope joined him there just in time to turn around and head back East for the New York location shots. That was when they found out that more happiness was in store for them. Their twosome was soon to become a threesome.

All this in the space of one year—stardom, two movies, marriage, parenthood. But Don didn’t seem surprised by any of it. He just goes along, taking it for granted that good things will happen to him. And, somehow, good things always do.

Unlike most of Hollywood’s successful citizens, Don is a stranger to the psychoanalyst’s couch, and he probably always will be. It’s simply not in his straightforward, outgoing nature to spend time thinking about himself or worrying about what’s going to happen next. He’s much too busy making it happen.

“I always knew I’d be an actor,” he says of his swift rise to success. “The thing that surprised me was finding out that I wasn’t a comedian, but a serious actor.”

This happened when Don had the part of the tragic Scotsman in “The Hasty Heart.” He was studying at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts at the time and one of the Academy directors spotted his dramatic ability. The director helped Don get a job in summer stock and the young actor’s early ideas of being a comedian became a thing of the past.

Don Murray grew up in the theatre. His father, Dennis Murray, was and still is, a well-known director. His mother, Ethel Cook, was one of the original Ziegfeld Follies girls. Don was actually born in Hollywood and, in a sense, his connection with the Fox studio might be said to have begun then, too, because his father was working as a dance director on the Fox lot when young Don was born.

Despite the fact that he looks like a Westerner, that there is an aura of the outdoors about him, Don was raised mostly in the East. When he was nine months old, his family began the move toward the Atlantic Ocean, pausing wherever Mr. Murray could get work, since the year was 1929-’30 and the Depression was abroad in the land. After brief pauses in Fort Worth and Cleveland, the Murrays—including Don, an older brother, Bill, and a young sister—settled in East Rockaway, on Long Island, where Don distinguished himself in high school sports but not in studies. He was an average student who excelled as a long-distance track runner, won his letter in football and played a fast game of basketball. In his freshman year, he spent whatever spare time he could find writing and directing scripts. When he didn’t like the quality of his classmates’ acting, Don decided to act the parts himself.

He tested for his first screen role at eighteen, but was considered too young for the part in “Bright Victory” which the studio had hoped to sign him for. He seemed so talented, however, that the front office offered to sign him to a ten-year contract, promising to “shape you into something colossal.”

Don thanked them but said he preferred growing to being shaped, and headed back to New York. It was while playing the role of the sailor in the Broadway production of “The Rose Tattoo” that Don met Hope. He and another young actor had arranged a double date.

From there on in, Don was determined to marry no one but Hope. But she was still in junior college, so he settled down to waiting for her to grow up. While waiting, he received his “Greetings” from Uncle Sam. Because of his religious convictions, he was listed as a conscientious objector and was assigned to two years of service in European refugee camps.

“I could never be a party to killing in any form,” Don explains this quite simply. As an alternate to military service, he chose to go overseas as a worker for the Church of the Brethren, which, like the Quakers, is a “peace” church. “I worked as a laborer and a mason, and did social work at night. I was paid $7.50 a month plus my board and lodging.”

He stayed a year in Kassel, Germany, and another year and a half in Naples, Italy. Here he worked at a camp among some 5,000 refugees, who were living in a state of abject misery behind barbed wire. This gripped his heart and mind. “Some of the suffering I saw there is indescribable. I’ll never forget it. And I vowed that someday, somehow, I would return and do what I could to help those wretchedly unhappy people.”

Now, having finished his second picture, “Bachelor Party,” Don is in a position to give important aid in a financial way. He and Hope plan to travel to Geneva, Switzerland, to work out a relief plan at the headquarters of the Church of the Brethren. He will also finance other volunteer workers, who will be sent to Naples, and will set up a regular program to which he will contribute in the future.

“Actually,” he says, “it will be a tithe. I’ll give a regular percentage of my future earnings for this work, for I think that a man’s religion is shown by what he does, not just by what he says. Besides,” he adds, “I’ve got a mighty lot to be thankful for. Helping people who haven’t been as lucky is sort of my way of saying ‘Thanks.’ ”

Yes, all in all, Don Murray will probably be known as the screen’s “good boy.” He even has a clause in his contract which states that he will never endorse a tobacco or alcohol advertisement. His example on the screen may help to change the style in leading men from gloomy young rebels in blue jeans to the image of a healthy-minded young man who believes that you’ll get farther by fighting for what you want than by rebelling against what you’ve got.

Maybe that’s what makes you think of cowboys and mountains and fresh air and bigness when you see Don Murray off-screen. Maybe it’s because he carries with him a sense of bigness that makes him genuinely impatient with petty people, petty jealousies. He’s a big man—170 pounds of very solid flesh and muscle—with big ideas and big ideals. He’s bound to make women in the audience sigh and recall a time when men were really rugged men and women were glad of it.

Don will inevitably be referred to as “a young Clark Gable,” but he’s not. He’s a young Don Murray, with an acting style and an appeal all his own. And, as one reviewer said of his “Bus Stop” performance, “When Don Murray tossed a lariat and caught Marilyn Monroe, he also caught his audience, and held them, fast.”

And Hollywood is holding fast to Don Murray, knowing that he’s going in just one direction—up.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1957

AUDIO BOOK