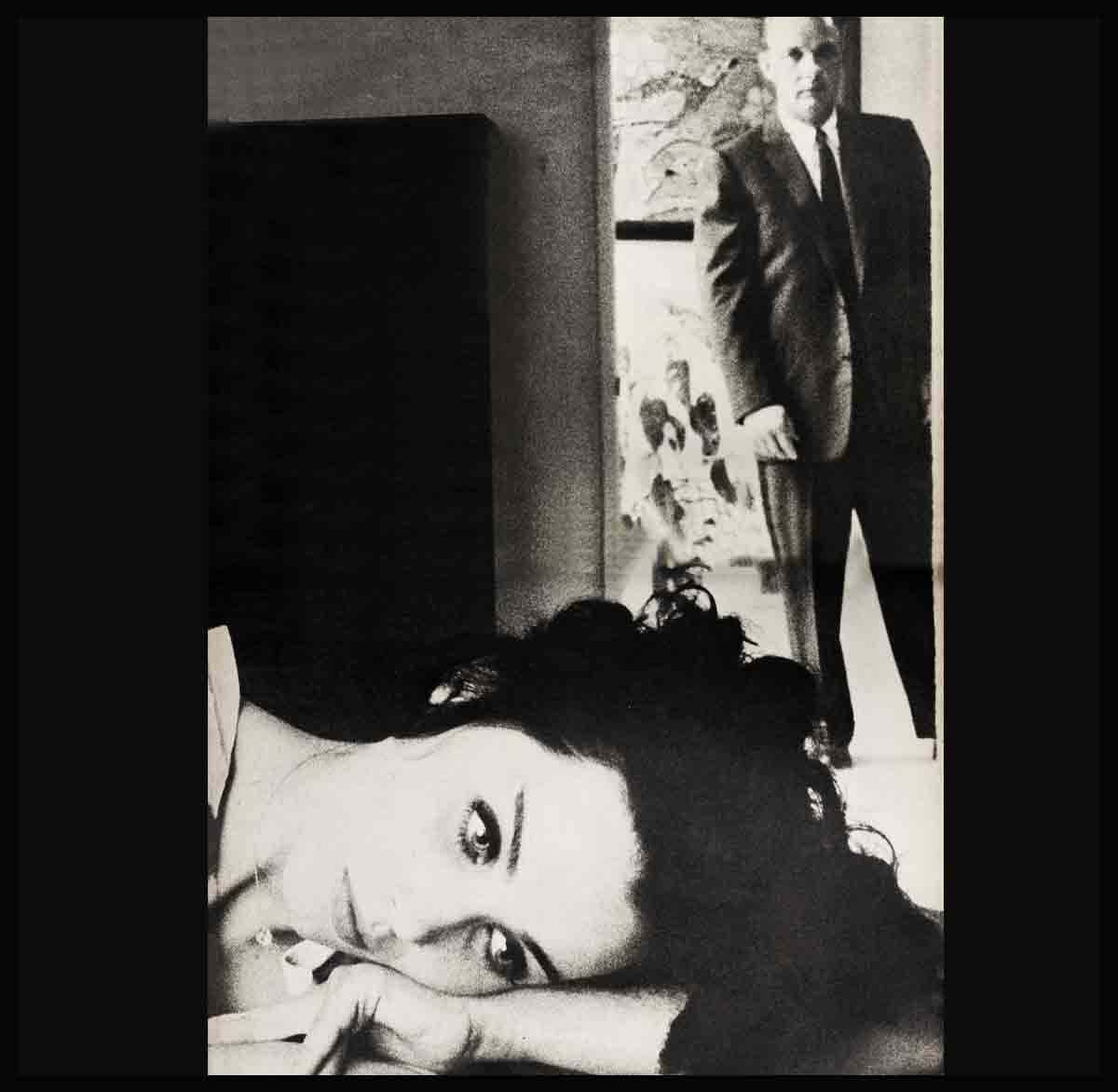

The House Of Terrified Women—Kathryn Crosby

A few miles away from the big house at 220 N. Layton Drive, Beverly Hills, the beautiful girl sat up in her bed. It was 10:40 o’clock of this mild and lovely Saturday evening, November 7th, 1959. The others, in the rooms flanking hers, in the stretch of rooms down the long and silent hallway—they were fast asleep by now. But she was not. She was sitting up, and she was dreaming, with her large blue eyes wide open, peering through the darkness, and beyond that darkness . . . dreaming back to an actual night in her life, nine years ago, when she was eleven.

She remembered it so well, so vividly, her first night in show business. Her parents had driven her to the radio station. Her uncle, Bing, had taken her hand and led her into the studio and over to the microphone. “And now folks, I’d like to introduce,” he had said, “a brand new singer, a sweet kid, my niece . . . Miss Cathy Crosby!” There had been applause, she remembered. Then silence. And then she had begun to sing her song, Dear Hearts and Gentle People.

Remembering, dreaming back, she began to hum that same song now.

She stopped suddenly when she heard the footsteps outside her door.

She figured that it was probably a night nurse, making her rounds, listening at doorways to see if you were asleep.

So she stopped her singing, and she waited, in the darkness, staring vacantly at a shadow on the wall ahead of her, until the footsteps—having stopped, too—moved on down the long and silent hallway of this place, this hospital, this institution, as some people called it.

And then, once again, still sitting up in her bed, the beautiful girl with the large blue eyes continued with her song. . . .

Preying on his mind

It was a few minutes after 10:40 that night when Bob Crosby entered the big house at 220 N. Layton Drive. He parked the golf clubs he was carrying in a foyer closet (he’d been playing that afternoon with Vice President Richard Nixon and actors Robert Sterling and George Murphy) and he walked into the living room.

His wife, June, was upstairs at the time, in her eight-year-old daughter Malia’s bedroom. The little girl had been suffering from a bad cold all that day, she had a slight fever now, she couldn’t sleep, and June had been sitting with her this past hour or so reading to her.

When June heard her husband enter, she lay down the book, got up from her chair and walked to the door.

“Bob,” she called, when she saw him.

She waited for him to answer.

Instead, she saw, he stood there motionless, in the center of the living room for a moment, mumbling to himself; and then he began to walk towards the big mirrored cabinet at the far end of the room, the cabinet where the whisky was.

June turned now, too, and walked back into Malia’s room, leaving the door open behind her.

“What’s the matter?” the little girl asked, softly, from her bed, seeing the look of worry, and fear, in her mother’s eyes.

“Nothing,” June whispered.

“Is Daddy home?”

June nodded.

Then she walked over to the little girl’s bed and took her hand in hers.

It was preying on his mind, June knew—preying on his mind, terribly. She could tell by the way he had looked a moment before. She could tell by the way he had looked that morning, when they’d gone to have a talk with Cathy’s doctor.

“What do you mean a complete breakdown?” he’d asked the doctor then. “I thought she only needed a week here. And now it’s a month and she’s still here. . . . What do you mean a complete breakdown, a mentalbreakdown?” he’d asked the doctor.

June’s hand, still clutching Malia’s, began to tremble now.

“Mommy,” the little girl asked, “are you all right, Mommy?”

“Yes,” June said. “Yes. Shhhhh. Yes.”

She looked away from her daughter and towards the door again.

She wished that her sons, Chris and Bobby and Steve, were back home from that party they’d gone to.

She wished, with all her heart, that Cathy were home, too, instead of in that place. . . .

Something is wrong

Cathy got out of her bed and rushed to a chair near the window and sat.

The feeling of faintness had overtaken her suddenly. She’d been singing one moment, remembering the nice tune, the nice night. And then her head had begun to spin and the tightness had grabbed at her stomach and she’d felt sick.

Something is wrong, she thought, sitting on the chair now, looking out the window, at the night. Somewhere, somehow, something is wrong.

She closed her eyes, tight.

She didn’t want to think about trouble.

The doctor had told her that she was here to rest, that she must rest as much as possible, and think pleasant thoughts, especially at night, at bedtime.

She had tried, too. Tried very hard. Every night this past long month.

But it was no use trying now.

Because she knew, deep down inside herself, that there was trouble.

And she thought of her father.

She saw him very clearly, though her eyes were still closed.

He was standing in front of her, looking at her, saying nothing.

He stood there for what seemed to be a very long time. And then he stepped back, back away from her, back in time, and into the den of their house.

He’d yelled at her mother that night Cathy remembered. He’d yelled so much that Cathy nine years old then, listening from the staircase, had run over to him and begged him to stop. He’d ordered her up to her room instead. And she’d gone. And for half an hour more, an hour more, she’d heard the yelling continue. Till finally it had ended and her mother had come to her room and they’d both sat and cried.

“Does it mean . . . when Daddy fights with you . . . does it mean he doesn’t love you any more?” Cathy had asked her mother that night.

“Of course he loves me, baby,” her mother had said, wiping away her tears, and her daughter’s. “This was just an argument. He’s nervous about his work. Something happened today and—”

She’d paused.

“Today he got a wire,” she’d said then. “It was from this booking agent in Atlantic City. This man said he’d just heard that Daddy doesn’t like any mention of his brother in any advertising, for any show he and the band are scheduled to do. And this man, he wired that either he be allowed to advertise daddy as ‘Bing Crosby’s brother, or else not to bother to come.

“And so Daddy was nervous tonight. And he had to pick on somebody. And he picked on me.

“It’s all happened before. It’ll happen again . . . I guess that’s just the way it’s got to be.”

“And the fights you have,” Cathy had asked, when her mother was finished explaining, “they don’t mean that Daddy doesn’t love you any more?”

“Of course not,” June had said.

“Because if he doesn’t love you,” Cathy had said, “how could he love me—or anybody . . . ?”

“He loves us, you and me,” her mother had said. “Very much. . . . Believe me.”

“I hope so, Mommy,” Cathy had said. “I hope so. . . .”

“I wish we were closer . . .”

“Oh, I hoped so, so much,” she said to herself now, sitting there in that hospital room, alone, remembering.

And as she said that, she saw his face again, in front of her, pale and angry.

This time he was yelling at her.

“Who were you out with tonight?” he asked.

“Dino,” Cathy said.

“I told you to stop seeing him,” he said.

“I love him, Daddy,” Cathy said.

“I don’t care,” he said. “He’s too old for you, for just one thing.”

“Thirteen years difference isn’t that much,” Cathy said.

“He’s divorced,” her father said. “Doesn’t that mean anything to you as a Catholic?”

“I love him,” Cathy said. “That’s all that means anything to me right now.”

Her father’s voice became louder.

“Have I denied you anything, before, ever, in your life?” he asked. “. . . How many other seventeen-year-old girls have gotten all the things I’ve given you?”

“Not many,” Cathy whispered, almost methodically, looking down.

“You have a convertible, pink and black, just the way you like it?”

“Yes,”

“You have pretty clothes? Closets of them?”

“Yes.”

“Have you gotten everything from me you’ve ever wanted?”

This time Cathy didn’t answer.

“Well?” he asked.

Cathy looked up and stepped towards him and put her arms around him. “Sometimes,” she said, “sometimes, Daddy, I’ve wished we could have been closer to each other. Sometimes I’ve wished there could have been fewer fights between us. Like now, Daddy. I know you’re thinking about me. It’s for her own good—I know that’s what you’re saying to yourself through all this. Just like you said the other times, with any other boyfriends I ever had, when you told me to get rid of them. ‘It’s for her own good’ you’re telling yourself, and—”

But her father didn’t seem to be listening to her.

“I don’t want you to see this Dino Castelli anymore,” he said, interrupting.

“I love him,” Cathy said.

“I don’t want you to see him,” he said, “and, for the time being, I don’t want you getting interested in anyone . . . You’re still just a baby, Cathy. Remember that. You don’t know what you’re doing. You’re like most kids today. With crazy ideas about life, romance, everything. Newfangled ideas about morality. Bad ideas. You take the Ten Commandments, and if there’s one of them you don’t like—”

He stopped, and he removed Cathy’s hands from around his waist.

“Now get to bed,” he said.

“Something I’m not guilty of . . .”

Cathy didn’t move.

“Did you hear me? Get to bed,” he said. “And from this moment on I want you to start acting respectable.” He shouted the word. “Respectable!”

“I haven’t done anything wrong,” Cathy said, still not moving.

“Oh Daddy, oh Daddy,” Cathy said, fighting back the tears. “What do you want from me? What do you expect me to do? Do you want me to go upstairs and lock myself in my room and stay there the rest of my life? Do you want me to get on my knees and beg your forgiveness for something I’m not guilty of?”

She gasped.

“Or do you just want me to go away?” she asked, suddenly.

He turned back to her.

“Is that what you really want to do,” he asked, “go away?”

Cathy shook her head. “I don’t know. . . . I don’t know what I want any more, Daddy,” she said. “I’m so confused.”

“I’ve said what I have to say,” he told her. “Now you do what you want.”

“Please, Daddy—” Cathy started to say.

“And if you do go,” he cut in, “be sure to leave your car keys. I’ll call you a cab.”

And with that he left the room. . . .

The memories of what had happened after that moment rushed through Cathy’s mind now. The cab that came to pick her up the next day. The flight to that tiny apartment on Dohany Drive. The two years on her own, making ends meet with the money she got from a few scattered nightclub and TV appearances. The breaking off with Dino in that time. The complete loneliness—broken only by occasional secret visits with her mother. The attempt at a reconciliation with her father last April, arranged and prayed for by her mother. The dinner at home again that night. The smiles from her dad. The hugging and the kissing and the tears of joy. And then—a few weeks later—the fights again, the bitter tears again, the bad words all over again, just like the old days. Until there was another flight, another apartment, another period of terrible loneliness and confusion.

Until there came that night, last month, when she could cope with it no longer.

And she collapsed.

And she was brought here, to this place. . . .

She opened her eyes and rose from her chair and walked across the dark little room to a sink.

She filled a glass with water and brought it to her lips.

There’s trouble again, she thought,—tonight. I know.

The house of terrified women

At the big house, at that moment, Bob Crosby put down the glass he’d been holding, rose and went to Malia’s room.

According to June, his wife, this is what happened next:

“He walked into the room and I could see he was feeling belligerent, that something was wrong. I suppose he had been drinking quite a bit. He usually does drink. I wanted to ask him where he’d been since his golf game ended. Except that I’m not supposed to ask. He has a persecution complex. He thinks everyone is against him.

“Yes, I could see that something was wrong, by the way he was still talking to himself, by the look in his eyes. I didn’t want any trouble in the baby’s room. So I-got off her bed and went to another room. I called our doctor and asked him if there was anything I could do. The doctor said no, just to keep quiet and not to get into an argument with him.

“I went back to Malia’s room, to see if he was still there. He was. As soon as he saw me this time he began to shout. It was something about where were the boys and why weren’t they home yet. I know it was mostly Cathy’s being in the hospital that was preying on his mind. But he didn’t mention that.

“Then, suddenly, in the presence of Malia, he began to walk over towards me and he began to beat me. He beat me unmercifully. He hit me about the head and nose and he broke one of my ribs.

“While he was hitting me I saw Malia, in her bed, watching, terrified. Then I saw this letter opener on the bureau. I picked it up. I didn’t mean to hurt him. I deliberately tried to inflict as minor damage as possible to scare him and make him stop beating me.

“When I saw the blood on his shirt, I dropped the letter opener to the floor and rushed to the phone again. This time I called the Beverly Hills police. I was in a panic. I said, ‘I’ve just stabbed my husband,’ and asked them to send over an ambulance, fast.

“But he was gone, out of the house, a few minutes later.

“Later I was to find out that he went to his brother Bing’s, and spent the night there. That he was to pass off the incident by saying, ‘I really don’t think June intended to do anything. She just got mad, so mad she didn’t know what she was doing. We’ve had family arguments before. I guess this one just exploded.’

“He said, too, ‘I’m not a wife-beater. I didn’t lay a finger on my wife. If my wife is hurt, it’s only because I had to use force to take the letter opener away from her. I’m the one who got stabbed, not her.’

“Its true. I’m not the one who got stabbed. Not with a letter opener.

“But for twenty-one years now I’ve been taking this, these constant arguments, constant fights. If you live with Bob on the inside you know he’s not the easy-going Crosby that the public imagines him to be. . . . This has been going on for twenty-one years. And I’ve had it, finally. I’ve put up with it for the sake of the children. Twice—once in 1943 and once in 1956—I started divorce proceedings against Bob. Both times I changed my mind. I took him back both times. But after everything now, this night, I’ve had it. I’ll never take him back. This is the end.”

What could be wrong?

At 12:05 that night, the nurse heard a report of the Crosby incident on the radio. At 12:20, while making her rounds of the hospital, she decided to have a look in Cathy’s room.

She was surprised to see Cathy, not in bed, but standing near the sink.

She was about to say something.

But before she had a chance, Cathy turned towards her and asked, “Is something wrong? Is that what you’ve come to tell me?”

The nurse shook her head.

“Of course not,” she said. “Nothing’s wrong. Nothing at all I was just checking the room down the hall and—”

She stopped as she saw Cathy begin to lean against the sink, hard, and grab it with her hands, as if she might fall. She rushed over to the girl, put her arm around her waist and began to lead her to the bed.

“Is it a bad dream you’ve been having tonight?” the nurse asked.

Cathy shrugged, “I . . . I don’t know.”

The nurse helped her into the bed, and then she lifted a sheet over her.

“Well,” she said, “the dream is over and done with and now you’re ready for a good night’s sleep, eh?”

Cathy didn’t answer.

“My, what a lovely night it is,” the nurse said, suddenly, turning towards the window and looking out. “Just lovely. . . . And tomorrow, tomorrow should be just as nice. I hope so, anyway. Because tomorrow, right after breakfast, we’re all going to take a walk on the grounds. And pick flowers.”

She had walked to the door and snapped off the light when she heard the girl ask, “And nothing’s wrong?”

She forced a great big smile.

“Really, child—what could be wrong on such a lovely night as this?” she said.

THE END

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1960