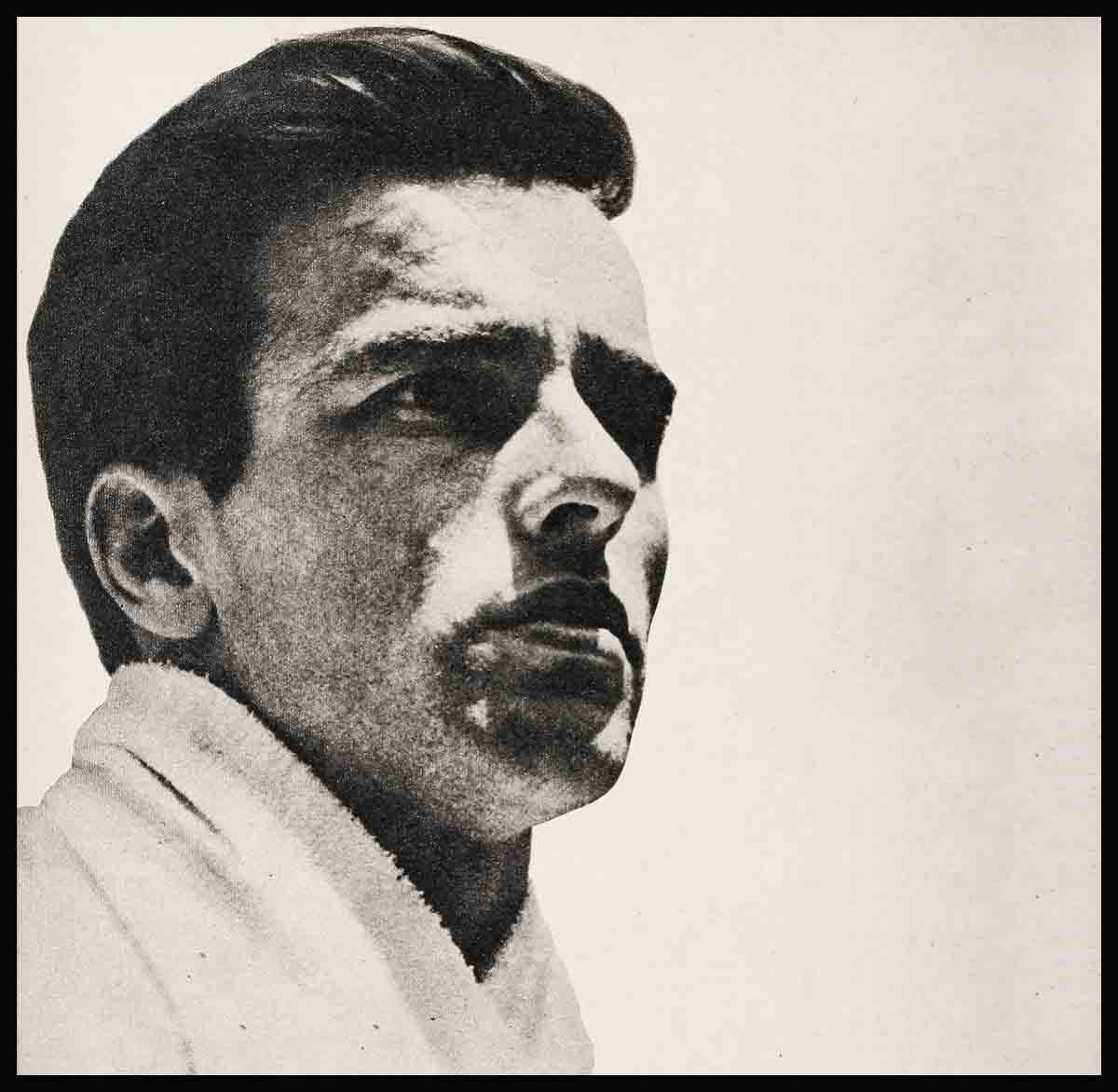

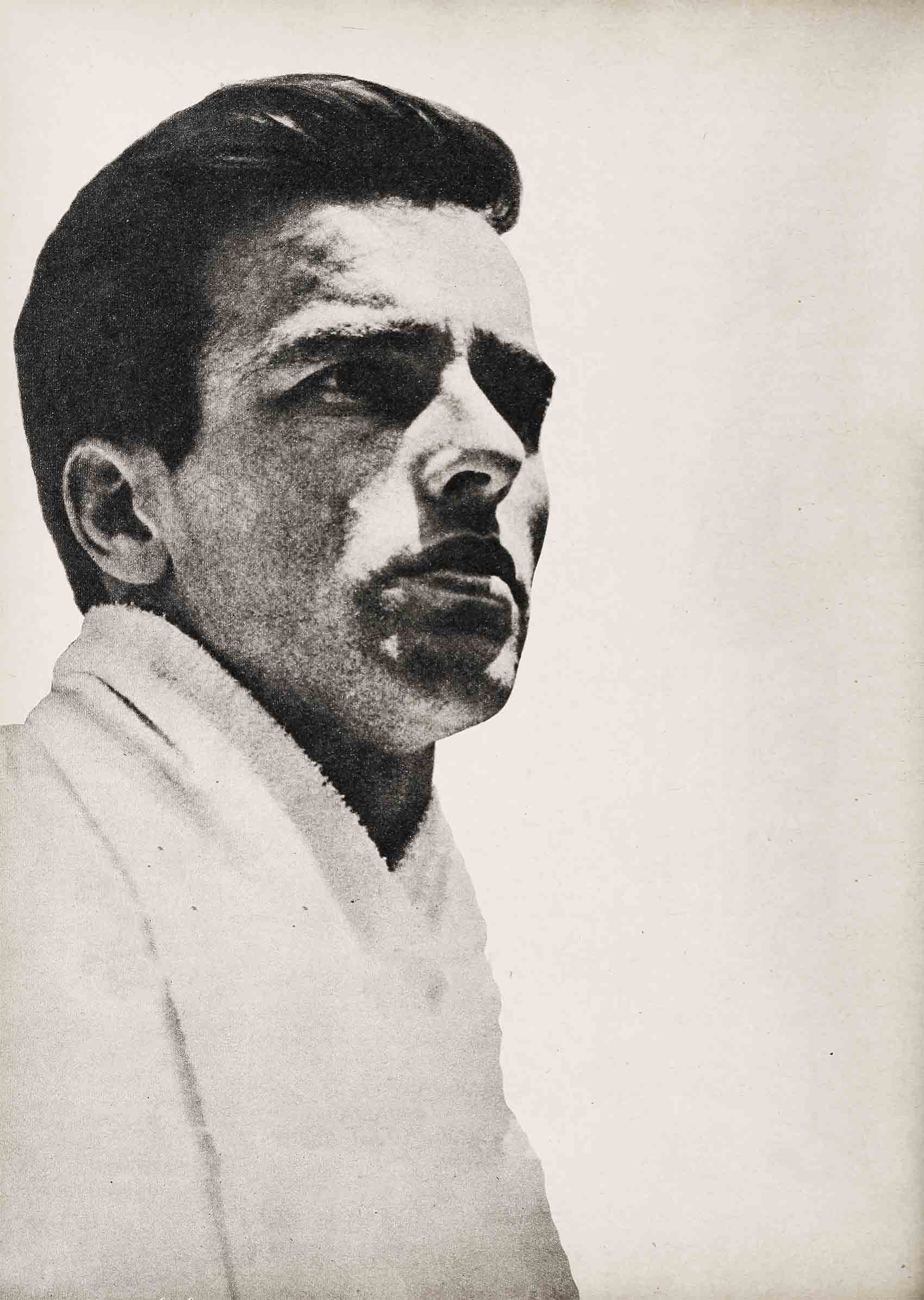

The Redemption Of Montgomery Clift

“This,” said Marlon Brando, sitting over a mid-morning cup of coffee on The Young Lions set in France, “is the first time I ever saw anybody in a special effects department addressed as honey by an entire movie location company!”

Marlon was talking about Olga Poliakoff, the small, pretty girl, pictured on the left, working on special effects for The Young Lions . . .

And just a few weeks after Marlon said that, there was somebody else who was amazed—and. Olga was part of that too.

The somebody else was an airline stewardess, and she was amazed at how well Monty looked, as he headed back to the States—handsome and erect, neatly-dressed, his shoes shined, his hands steady, his mind sober—cold sober. She thought back to that last trip, when he had been on his way to France. She remembered how bad he’d looked then—even worse than the other times: his face sallow and drawn, heavy rings under his eyes, nervous and unsteady and with a look on his face of the haunted, the hunted: of a man who was trying to destroy himself.

She remembered, too, the stories some of the other members of The Young Lions company, a little loaded on free airplane champagne by the time they were halfway over the Atlantic, told about Monty . . .

She remembered, for one, the story about how only a few nights earlier in Hollywood a bigtime producer had thrown a party, how midway through the party the producer had proudly asked everyone to step into his private projection room to see a run-through of his latest movie, how halfway through the picture Monty—who’d been pouring down the straight Scotches—suddenly began to holler and yell so much the movie had to be stopped and the producer, embarrassed, had to bid all his guests good night.

And she remembered the story they told about Monty on Southern location for Raintree County a few months back, how he’d gotten so angry the day he arrived and learned a co-star was being given fancier living accommodations than he that he proceeded to take a few drinks of something and then go about destroying practically every piece of furniture in his cabin; how the next day, hung over, so hung over he could barely walk, he showed up for his first scene shaking all over; how when the time came for him to step up into a buggy in that scene he got into the buggy, all right, but ended up a moment later falling flat on his face and out over the other side.

The stewardess remembered these stories and stared at him now. The plane was just about io take off from the Paris airport, and Monty sat strapped into his seat looking out the small window of the plane, his eyes clear, a smile on his face, Waving goodbye to somebody, excitedly but at the same time a little sadly, like a young boy going off on a long trip alone, leaving a lot he loves behind him, but happy and strong just the same.

The stewardess stared. And she couldn’t help wonder what had happened to make this change. . . .

Floundering in the canal

Actually, it all began that day a little over four weeks earlier. The place was a narrow canal which ribbons its way along the lovely countryside just outside Paris. The time was late afternoon. The Young Lions company had been there all day shooting an important scene, one in which Monty flounders in the water and is finally pulled out. They had just completed the last take.

“That should sober him, if nothing else does,” a crew member snickered.

The girl standing next to him ignored his remark. She’d been standing there for the last few hours watching Monty swim back and forth in the cold water and she kept her eyes on him now. She watched them pull him to the canal bank. She watched as one of the assistant directors went over to him with a big heavy blanket and handed it to him. She watched as Monty shook his head at the director and the blanket and walked a few yards away, as he sat down on the grass, still soaking wet, shivering, alone, away from everybody.

Suddenly, not knowing exactly what she was doing, why she was doing it, the girl began to walk over to where he sat. She stopped on the way to pick up the blanket the assistant director had dropped after trying to hand it to Monty, and then pausing just a moment—was what she was doing right, she wondered; too forward? too interfering?—she walked over to where he sat and draped the blanket around his shoulders.

He looked up angry expression in his eyes, as if to say who are you and what do you want and why don’t you leave me alone? But when he saw the girl—she was pretty, even though she looked frightened, with a round clear-skinned face and sky-blue eyes, very large, very warm, and with her hair cut like a tomboy’s, the way most girls were wearing their hair these days—when he saw her, the angry expression disappeared and he smiled.

“Bonjour,” he said.

“Bonjour,” the girl smiled back.

He motioned for her to sit down next to him.

After a long moment, she did.

For a few minutes, neither of them said anything.

Tomboy’s admiration

And then, slowly, as the coldness left Monty’s body and the shyness began to find its way out of the girl, they began to talk.

Nobody has any way of knowing what they said to one another. All that is known about the next hour is that they sat there talking, that the girl told him her name was Olga, that she was working on the movie, that she’d been an admirer of Monty’s ever since she was a girl of fourteen and his first picture, The Search, was released. It’s known, too, that Monty was so entranced by this young girl with the warm blue eyes and the tomboy haircut by the end of their hour together that he asked her if she would have dinner with him that night. And that she smiled and said yes.

“Monty and the girl were inseparable after that,” a studio executive who was in Paris at the time recalls. “They were together on the set practically all the time for the five weeks of shooting and as soon as the shooting was over Monty would rush for his car and pick her up at the cate and they’d drive off. It was a beautiful thing all around, for them—and for us. For us it was great because for the first time in a long time Monty didn’t give us any trouble. The whole thing, his relationship with this girl, seemed to straighten him out the way he hadn’t been straightened out in years. There was a big cutdown in his drinking and there were no tantrums to put up with. And he wasn’t the lone wolf of the company for a change, the pathetic lone wolf who never wanted to talk to anybody . . .”

Candlelight and wine

“One night my wife and I decided to go out to dinner,” another person connected with the picture has said. “I saw them, sitting at a candle-lit table over in the corner, Monty and this special-effects girl who was working on the picture. They sat holding hands, looking into each other’s eyes, ignoring everything else around them. Once in a while they would let go of their hands long enough to eat a little or sip a little wine. But for most of the time we were there they just sat, looking at one another, talking, sometimes laughing, sometimes not, and acting very much like the desperately-in-love young couple my wife wished that we still were . . .”

The last rendezvous

This writer learned about Monty and Olga the day he arrived in Paris to do a story on The Young Lionscompany. As soon as I got to my hotel I phoned the man in charge of publicity and told him I wanted to set up interviews with both Marlon and Monty.

“Marlon will be around for a few more days,” I was told, “but Monty’s all through with Paris locations today and has to fly back to Hollywood. In fact, as far as I know, he’s just checked out of his hotel and he’s on his way to the airport.”

I was disappointed. I’d especially wanted to see Monty again. The last few stories I’d written on him had all been about his heavy drinking, the accidents that had almost taken his life, the rock-bottom emotional level he’d hit—and I wanted to see if maybe, by some miracle, something hadn’t happened to change all that, at least a little.

I phoned the airport.

“Oui, Monsieur Clift is here,” I was told. “His plane is delayed and he will not leave for another hour.”

I decided to try to catch him at the airport, just to talk to him for a few minutes before he went back home.

I got to the airport, quite a way outside Paris, about three minutes too late.

That is, it was too late to get to talk to Monty. His plane hadn’t taken off yet and I saw him standing on the other side of the closed fence, near the stairway leading up to the plane, but he was talking to a girl.

I watched them talking for a few minutes until an exasperated French airport official came rushing over to them and, his hands flying around with more fervor than the airplanes overhead, begged them to break it up, for Monty to get on the plane so it could take off.

A flying kiss

Monty nodded. And then, as the girl touched his arm gently and began to walk away, he ran a few steps after her, grabbed her, spun her around, took her in his arms and kissed her.

A minute later, he was on the plane and the girl was on the side of the fence where I stood, standing directly alongside me, looking desperately over toward the plane, from little window to little window, trying to catch Monty’s face, then finally spotting him and throwing up her arm and whispering, “Au revoir, Monty . . . goodbye. . . .”

I was introduced to her after the plane left by some of the other members of the company whom I knew, and who’d come to the airport to say bon voyage to Monty and a couple of the others who were going back to the States with him. They’d obviously been having a small party before they’d driven out from Paris. And they were obviously in a mood to continue it when they got back to town.

“Will you come, Olga?” one of them asked as they headed back to their cars.

Olga said she didn’t think so. She was tired, she said, and she wanted to get back to her apartment and rest.

Then they asked me if Id like to go along.

I, too, was tired from my long trip, I told them, and if they didn’t mind. . . .

“Oh, not at all, not at all,” they called bee piling into their cars and driving of.

Olga and I were alone now. She asked if she could give me a lift back into town. I accepted.

Back from the dead

It was as we were riding back to Paris that she told me a little about herself and Monty. She knew I was a writer and, knowing that Monty wasn’t too fond of writers, she was very careful in what she told me. about some things, especially about that first day they’d met, after Monty had been pulled out of the cold canal water— “He looked like a little wet puppy dog,” she said, “so alone, so shivering”—and she’d gone over to him with the warm blanket and draped it around his shoulders.

The rest of the story, I knew, I would have to a from other people, as I eventually did.

But all the same I could tell now, during our ride back to Paris, having known this sweet young girl for only a little while, that she was the person responsible for the change I’d been able to

port for these few minutes a little while back, the change the airplane stewardess , I talked to weeks later had noticed, the change everyone who’d been in contact with Monty for the past five weeks had noticed. This, I half-realized now and was to find out later, this was the girl who had succeeded in bringing a lost soul back from the dead, in bringing love back to a man who’d begun to wipe love from his life with fear and drink, disappointment and distrust.

“When do you expect to see Monty again, Olga?” I asked. “Did he say anything at all about coming back?”

The burning question

Olga pretended not to hear me. And, a moment later, I looked straight ahead at the road and pretended not to notice her reach for her handkerchief and wipe her eyes.

Even though we began talking again within a little while, about other things—Paris and wines and where-to-go and what-to-see—my question seemed to linger in the car, silent and unanswered and yet still there.

“Did he say anything at all about coming back?”

And as I kept hearing it, I thought how good it would be, for both of them—the boy who’d been saved and the girl who’d saved him—if some day he did. . . .

THE END

—BY PARKER D. BREWER

See Monty in MGM’s RAINTREE COUNTY and watch for him in 20th Century-Fox’s THE YOUNG LIONS.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1957