Love And Marriage—Debbie Reynolds & Eddie Fisher

The tired young troubadour in green corduroy slacks and sweater was slumped happily in a chair in his NBC dressing room. As he spoke, every other word sounded like music.

“It’s all worked out wonderfully,” Eddie Fisher was saying—of love and marriage and two very | successful careers. “Everything’s beautiful, boy!”

He reached for the phone and asked for a familiar number. “I want to talk to my wife,” he said. Not in essence a very lyrical line, but Eddie read it like something out of Shakespeare. After all, he hadn’t talked to her for approximately two hours.

It was Wednesday, the day he makes music from morning until midnight, doing one live and one kinescoped Coke Time television show. Outside it was beginning to rain, and the line was already forming for his late-late show.

But he was between shows now. The traffic had thinned in his room. The friends, the disc jockeys, the agents, and the song-pluggers had left. The fans screaming “Eddie-eee” had been stilled. His devoted Dungaree Dolls, with their initialed jeans and orange sweaters, had descended upon him and gone. But soon, they would return.

Soon the studio would be coming to life with Eddie Fisher’s smile and his warmth and all the music which spills out of him. But now, he was alone with his own heart again. And with another life—so endearingly shared.

“You aren’t alone, are you? Who’s with you now?” he asked Debbie, who was home recuperating from some dental surgery.

The maid was there, she said. As soon as he hung up, Eddie dialed her parents in Burbank, asking them to please trek out to the Pacific Palisades and stay with Debbie until he could get there, so she wouldn’t be lonely.

“I know she’s a big girl now,” he agreed. “But she isn’t feeling well. Can you go? Right away?”

Similarly, Debbie’s first concern was for him, and whether her tooth trouble would delay their taking off on his planned personal appearances.

During the first eight months of being Debbie and Eddie Fisher, these two happily-marrieds have commuted back and forth across the country for their respective careers. They’d spent the last three months on the West Coast until Debbie completed her M-G-M movie, “A Catered Affair.” Then they planned to lock up their farmhouse in the Pacific Palisades and head for New York and two months of television and personal appearances.

For all their popularity, and for all those who were once skeptical, Debbie and Eddie have worked out their own successful pattern for living with no strain, synchronizing their personal lives and careers and avoiding separations.

“But it’s not really a question of not being separated. It’s a question of being together,” Eddie was saying earnestly now. “It’s no marriage unless you’re together. Marriage means together.” And now, with a baby on the way, this is more important than ever.

However, Eddie adds enthusiastically. “I wouldn’t want Debbie to give up her career. I’ve never minded it, and I’ve always known she must not give it up. In fact, I wouldn’t let her give it up. I don’t think she should. She’s a great little entertainer, and she’s just scratched the surface.”

Equally, he’s happy when they hit the road together. “I like to travel around. I like to meet new people.”

Debbie’s picture finished, they took to the skies again, dropping in on the people—the important people—who live between New York and Hollywood. A true minstrel man, Eddie loves taking his music personally to them.

“I’d like to make more personal appearances than I have made, actually. You can get stale. And I’d like to work a theatre date again, too, here and there. You’ve got to do this sometimes to keep in shape. It’s the same as being a fighter—you’ve got to keep in shape. I feel that’s a responsibility to the public, and there’s nothing like working in front of live audiences to keep you in shape. Debbie does a lot of the shows with me. They really love her.”

Eddie’s sure her career will never interfere with their life together. “Debbie would never allow that,” he says. On the other hand, he doesn’t want Debbie’s career to suffer because of his schedule. “They sneak-previewed ‘The Catered Affair’ the other night, and I understand it’s fabulous.” He further understood that this was her first dramatic role, co-starring with Bette Davis and Ernest Borgnine.

Similarly, nobody understands better than Debbie, Eddie’s urgency to keep on the move with his music. As he was saying, “I like to go back and forth. I love it out here in Hollywood, and we have the most wonderful house leased until September. When we’re making movies our home will be here. I love the sunshine but, after three months here, I’m still waiting for some,” Eddie laughed, remembering the drizzle outside. “But I like it in New York, too. There’s a certain hum back there that I like.”

A “hum” that’s home to him, for Eddie was born to the tempo, the raw exciting beat of the city. Its sounds—the symphony of tenements and skyscrapers and subways—are familiar music to him.

Debbie, on the other hand, was bred in the breezy freedom, the openness of Western living—until Fate tapped her shoulder and sent her around the hill from Burbank—into the magic of make-believe.

Today, theirs is one tempo, one beat. The East and the West, the twain have met and are meeting continuously. And Debbie and Eddie are proving today that these two, born with the magical stuff that dreams are made of, are blessed with the sterner stuff that marriage is made of, too.

Compliment Eddie Fisher on how successfully they’re acclimating and he sparkles, “Why, sure! We’ve been very lucky. We’re very happy.”

Their careers are just another bond between them, Debbie and Eddie say. “We share the same interests, and I think it’s wonderful,” Debbie says, as her husband enthuses, “It’s worked out wonderfully.”

But it isn’t working out accidentally. Luck has had little to do with their happiness.

Of course, theirs is a heritage of faith and strong family ties and the toughness of spirit to overcome obstacles. Neither of them was born into wealth, and both were early instilled with their sense of values.

But their heritage has been strengthened by experience. Eddie and Debbie were well seasoned to problems and any career-conflicts before their marriage. They’re veterans in that. With them, the preliminary—their courtship—was tougher than the main event. Distance and misunderstandings, intensified and falsified by gossip columnists, were almost too much. But theirs was a determined love against any odds, and when they married they were prepared to commute coast-to-coast or make any compromises necessary for their future happiness.

From the beginning, Debbie’s had positive ideas about a woman’s place in marriage versus a career. “If both careers are on a full-time schedule, one of them will have to give up a few things—and that one should be the girl,” Debbie would say. And that she is giving them up, if necessary, nobody who knows Debbie ever doubted.

Neither of them takes any credit for synchronizing their lives and the careers of two of the public’s most popular young idols. But both have credit coming, plenty of it.

As much as he likes to keep his show on the road, Eddie turned down some fabulous offers while Debbie was before the cameras, saying, “Debbie’s picture isn’t finished, and I don’t want to leave her alone.”

When contractual legalities threatened to prevent Debbie from being on a television Spectacular of Eddie’s, she made it reasonably clear that, if this wasn’t cleared up, she would never again appear on television to plug a movie—not even her own.

Debbie turned down a great part in “Time out for Tammy” at first, when an early production date would have kept her from going East with Eddie. A part, ironically enough, that Eddie had been instrumental in bringing to her attention.

Universal-International had submitted the script to Eddie. He read it and loved it, but as he told his MCA agent Danny Welkes, “It’s not for me, but this is something Debbie ought to see.” He instructed Danny to send it to Debbie’s agent, explaining, “It’s a dramatic part, and I’m not ready for dramatic things. But the girl’s part would be wonderful for her.”

Debbie loved the script and pitched for her studio to loan her to U-I. They were negotiating with Warner Brothers for Tab Hunter for the male lead. Then she found out they planned to begin shooting right away, so she told them she couldn’t do it. “Eddie has to go to New York, and I won’t be separated from him that long.”

But the studio postponed the starting date, so it looks like Debbie might do it after all.

While Debbie was hospitalized for dental surgery, Eddie crowned four queens for her. He was a busy baritone that night, singing on an NBC-TV Spectacular, making trips back and forth to Burbank to the hospital, singing on a telethon at the Shrine Auditorium, and stopping at the Statler Hotel en route to keep “Debbie’s deal—crowning queens from Santa Barbara and all over.”

At the telethon, Eddie was scheduled to sing a request for one of the arthritis victims on the stage. “What would you like to hear?” he asked.

“Heart,” she said.

“You’ve Gotta Have Heart,” Eddie began—and she started crying, almost breaking him up. “I have another song to dedicate,” he went on finally, “to a girl named Mary Frances in St. Joseph’s Hospital in Burbank. ‘I Need You Now’—”

As he told Debbie later that night, “You know, that was no kidding. The lady was crying, and I didn’t know what to do. I did need you.”

Debbie had thought she would be hospitalized for only two days. She had four impacted wisdom teeth, and before going East, she thought she would have her hometown dentist extract them. But it turned into complicated surgery. As Debbie described it later, “The doctor said he could have performed two appendectomies and removed an ulcer in the same time it took to get my teeth out.” She went into post-operative shock, they had to administer plasma, and there was fear at first that the nerve in her face would collapse and her lip be paralyzed for four months.

During the two hours and twenty minutes Debbie was in dental surgery, Eddie almost went out of his mind, wondering why it was taking so long. When he wasn’t working, Eddie would be there with her, and after his shows he would just sit there beside her until he was sure she was asleep. That was all he could do to—her. As he said later, “I felt so helpless.”

And Debbie was doubly miserable, thinking of Eddie’s tight, cross-country schedule of personal appearances, and wondering how her hospitalization might affect that. She was full of woe, a small dejected heap with chipmunk cheeks, one of them black and blue. She kept worrying whether anyone ‘would think, “I’m just being a glamour girl and making like a movie star—staying here in bed in the hospital.”

“Look in the mirror, Frannie,” her mother would tell her. “You don’t look like any movie star.”

“I’m just a big sissy,” she would wail. “I never do anything right. If I have chicken pox, I have it three times the size. And four teeth pulled—and this—”

But take her husband’s word for it, “She was no sissy, let me tell you. She was very brave. I was more scared than she was.”

His was a “tight schedule” all right. Enroute East, he was stopping over to do a show for the Army in El Paso, Texas, making an appearance in New Orleans, crowning the Azalea Queen in Mobile, Alabama, and doing two Coke Time television shows in Atlanta, Georgia. Meanwhile, a recording date had been scheduled before he departed. “I’ll be making twenty-six records, including an album of Academy Award tunes. I don’t see how we’re going to get it all in—and make the plane out of here.

“When we get to New York, they’re introducing the family-sized bottle of Coke, and for three days I’ll be making appearances for that from early in the morning until late at night. I’ll be doing my TV show from there, and I’m going to Tennessee. . . .”

Not that Eddie Fisher has any complaints. This is what he had hoped for—almost starved for—all those lean years.

“This is what I’ve always wanted. I’m young, I can take it, and it’s good experience. And I like it, anyway.”

It would take a girl like Debbie Reynolds, a girl seasoned to the demands of a successful career, to understand a schedule like Eddie Fisher’s. And a girl who loves him very much—to understand his dedication to making music, all the music he can for all the people he can.

“I like the pace, but I want our life, too,” Eddie was saying, never a thought away from the girl who’s brought another kind of music—her own music—into his life.

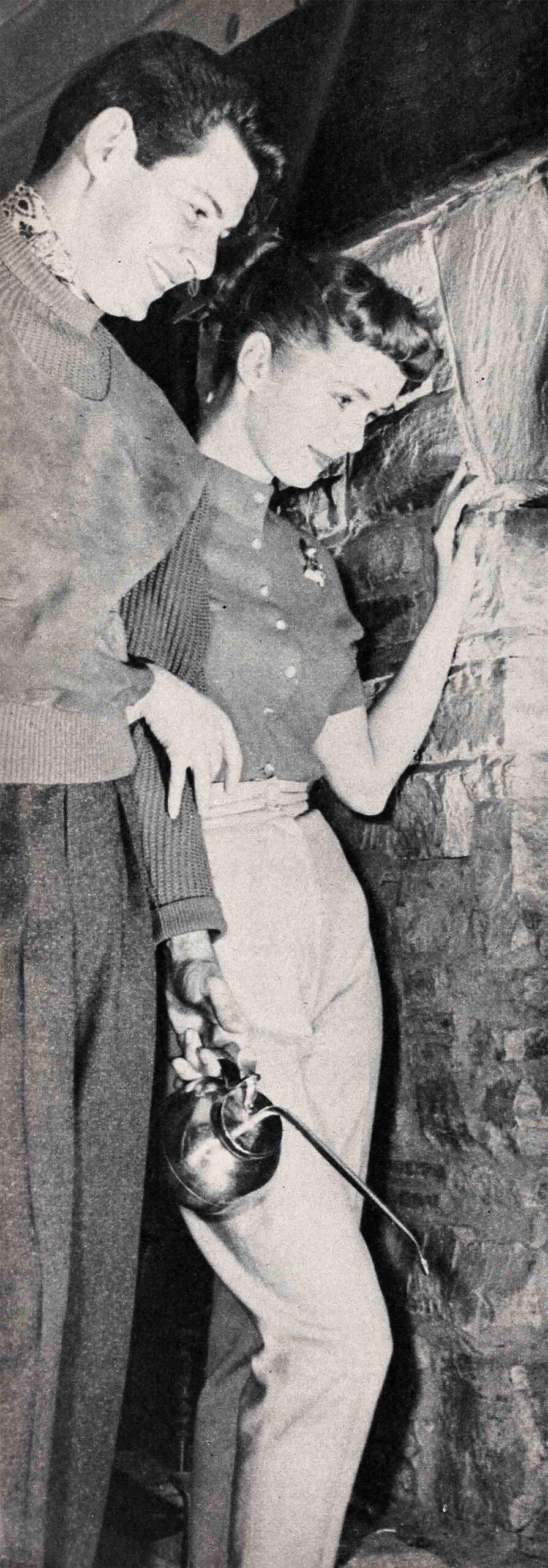

“Home” in Hollywood—Eddie’s first since leaving Philadelphia ten years ago—is a three-bedroom Provincial farmhouse which wanders cheerfully and comfortably around various levels in the middle of their seven acres in the Pacific Palisades. “Isn’t it a wonderful house?” Eddie enthuses. “It’s just the greatest house I’ve ever seen. Debbie found it, and she couldn’t have picked a better one. It’s so homey—I guess that’s what you’d call it. It’s not elaborate, everything’s made for comfort. And it’s an old house, but I like old things. It’s such a relaxing house you fall in a chair and you don’t get up for—well, for two minutes,” he grins, remembering his schedule.

The house is set far off Sunset Boulevard at the end of a winding road lined with tall eucalyptus trees. “Honey” is the word for the lodge-sized living room with its white wormwood paneling, beamed ceiling, large stone fireplace, all the hanging copper and pewter, the chintzy sofas and deep easy chairs and Mrs. Fisher’s prized collection of Royal Doulton figurines—of which Eddie admits, “I don’t understand those things. Debbie loves them though.”

Their master bedroom is crimson-carpeted, has a fireplace, a king-size blue-canopied mahogany four-poster bed, floral wallpaper and crisp white organdy Priscilla curtains. Eddie uses one of the other bedrooms for an office, employing a full-time secretary, Eileen Thomas.

Debbie and Eddie have individual dressing rooms off the hall. There’s a row of framed colored photos of Debbie over his wardrobe, and a sign admonishing, “Keep Your Temper—No One Else Wants It—” from Eddie to Eddie. His wardrobe bulges with his favorite sport clothes, including a handsome tan-checked Eisenhower jacket Debbie gave him, plus an out-sized plaid number she just couldn’t resist.

“She’s always buying me clothes. Always coming home with a shirt, sweater, socks or something,” her husband says fondly. “The other day she came in with this plaid jacket saying, ‘Here—fix it up.’ It’s four sizes too big, but beautiful.” Eddie’s currently on a corduroy kick, “Like these slacks I have on now. They’re Italian corduroy. Debbie’s mother alters them for me. She charges me fifty cents a pair—and I never pay her.” Since Eddie’s fat new NBC contract, Mrs. Reynolds has been threatening to raise the price to a dollar a pair, but there’s no problem in higher finance since they keep it all on the cuff anyway.

Besides the main house, there’s a swimming pool the owner recently put in, and there are a number of interesting smaller buildings, including a charming little guest house and an Early American playhouse—an intriguing little building with its rooms labeled, “Barbecue Room,” “Gin Rummy Room,” “Piano Room,” and soon. Here, too, are stored a number of mystery trunks full of Eddie’s New York things, which his valet Willard packed for him. He has only a vague memory of what’s inside them, and there’s never been any time to unpack.

Their boxer, Charlie (given them by Eddie Cantor)—so named because he looks like Charlie Chaplin, with his white nose and black mustache—even has his own little heated house and acreage that Debbie’s dad fenced in for them. In addition to Charlie, their household consists of Willard, who came out from New York with Eddie, their maid and her little boy, a part-time housekeeper, and two newly acclimated white cats they’ve named Sarah and Harry—which sometimes makes for some understandable confusion, since Eddie and Debbie call each other Sarah and Harry.

Their first big party, given for The Thalians (a philanthropic organization of younger members of the entertainment industry), was a family success. Debbie, in a ballerina-length long-sleeved blue lace dress, and Eddie, sporting a bright red vest and an ever-puffing pipe, did themselves proud. Debbie’s mother made the hot hors d’oeuvres and, when the maid became ill at the last minute, did K.P. duty as well. Debbie’s “adopted brother,” Paul Lillard, was also there lending a helping hand. Once Debbie missed Eddie, then found him taking a party of guests on a personally conducted tour of their home.

They leased the place furnished, moving in with their clothes, Debbie’s figurines, their trophies and Eddie’s gold records, and a room full of elegant silver wedding gifts they’re saving to use in their own home when they build or buy one. Many of Debbie’s hometown friends had waited until the Fishers came West—and they could find out what she needed—before getting a gift. The word soon got around among them that Mrs. Fisher had “everything silver—but everything—but not a thing we can use for everyday, not even one pot-holder of our own.”

One of Debbie’s friends immediately gifted her with a can opener, “So I’ll know you won’t starve to death.” Another started her a service of cooking utensils. But one girlfriend reflected the concern of the many when she kept worrying about giving such undistinguished items. “Dish towels? How could I give Mrs. Eddie Fisher dish towels?” she said, shocked by the mere idea. “Just forget Mrs. Fisher, and think of Frannie Reynolds,” Debbie’s mother told her, “and she needs pot-holders and dish towels.”

Take Eddie’s word for it, Debbie’s perfect as a homemaker. “She really loves her home. And don’t ever believe she can’t cook, either.” What? “Well—she makes wonderful enchilladas and tacos, there’s a sort of casserole thing, and—well, she’s been working at the studio most of the time since we’ve been out here,” he says, rallying gallantly.

As one of the highest-ranking Girl Scouts—with some forty-seven merit badges—Mrs, Fisher’s a whiz at cooking out of doors over a hole in the ground, but this still limits her comparatively now.

And for all her merit badges, it’s cute the way Eddie keeps a protective eye out for her, always looking after her with, “You’d better put on an extra sweater, it’s getting chilly.” Or, frowning on her habit of going barefoot around the place, “Sarah, please put on your shoes.”

Domestically, Eddie’s quick to admit his own limitations. “I’m nothing around the house. It’s not so nice to have a man around the house. I guess I’m just a chess player around the house.”

And believe him, it’s nice to have a Girl Scout around their house, especially at such times as that morning not long ago when a fire broke out on their place. Debbie’s father and her best girlfriend, Jeanette Johnson, were visiting them, and when the fire was discovered the three of them calmly went into action “like they were used to putting out fires every day,” Eddie’s pal, Bernie Rich, says, ribbing him. “Everybody moving with precision, doing things like they were mechanized.” With no excitement, Jeanette picked up the phone and called the fire department. Debbie’s father got down the fire extinguisher, and Debbie barefooted it out on the lawn with him. Together, they had the fire extinguished by the time the fire engines got there.

Eddie? “He was home. He just didn’t know what to do.” He stood there watching the whole scene—the firemen with the trucks idling. Debbie and her father calmly turning off water hose and gathering up their extinguisher. Finally, he managed to say with some authority, “Sarah, put on your shoes!”

The Fishers have a film projection booth at one end of the living room, and they love running movies at home. Their best friends number TV actor Bernie Rich, Eddie’s boyhood friend from Philadelphia, and his pretty red-headed actress-wife, Marjorie Duncan, who used to work on the same radio show with Eddie when they were kids. The four of them, together with an occasional boxer, wedge into Eddie’s Mercedes-Benz whenever they can and head for a spontaneous outing in Palm Springs or Desert Hot Springs, which always turns out “just a big bunch of fun.”

They have two palominos given to them by Eddie’s sponsors and named—naturally—Coke and Cola. And they have had dashing Western riding clothes made, “but we’ve only been riding once.” Eddie plays chess occasionally with Debbie’s father, “and I’m still trying to teach her.” Actually, with their combined working hours, “we don’t do much of anything, and getting moved into the house and all—”

Debbie insists that Eddie is of the opinion she talks too much. “He says I talk all the time.” But weighing it philosophically Eddie says, “She’s a woman. She talks—but I get a few words in.” On the other hand, Eddie insists he’s the moody one. “Debbie doesn’t know what the word moody means, but I’m moody—not with her. Usually something to do with my work.”

Together, both can take with good humor any occasional slip of the typewriter concerning them. At Jimmy Durante’s birthday party when, after Eddie’s insistent, “Come on, Sarah, and sing,” she rendered a few numbers, Eddie cracked, “You know, she’s become quite a personality since she married me.” But, as he admitted now, “I was just kidding. A columnist had said that I had become quite a personality since I married her. And you know something? He’s right. I have,” he laughed.

Together, their different tempos of living don’t matter too much. Eddie’s used to revolving with a crowd wherever he is, and he’s geared professionally to New York living and night hours. Debbie’s used to being up by 7 a.m. and on the set early. Their working hours are usually in reverse. Eddie often does one live and one filmed show on Wednesdays and Fridays, getting home very late. He has recording dates on at night and on Sundays. On Tuesdays and Thursdays his television production staff gathers at his home, running over the music and planning forth- coming shows.

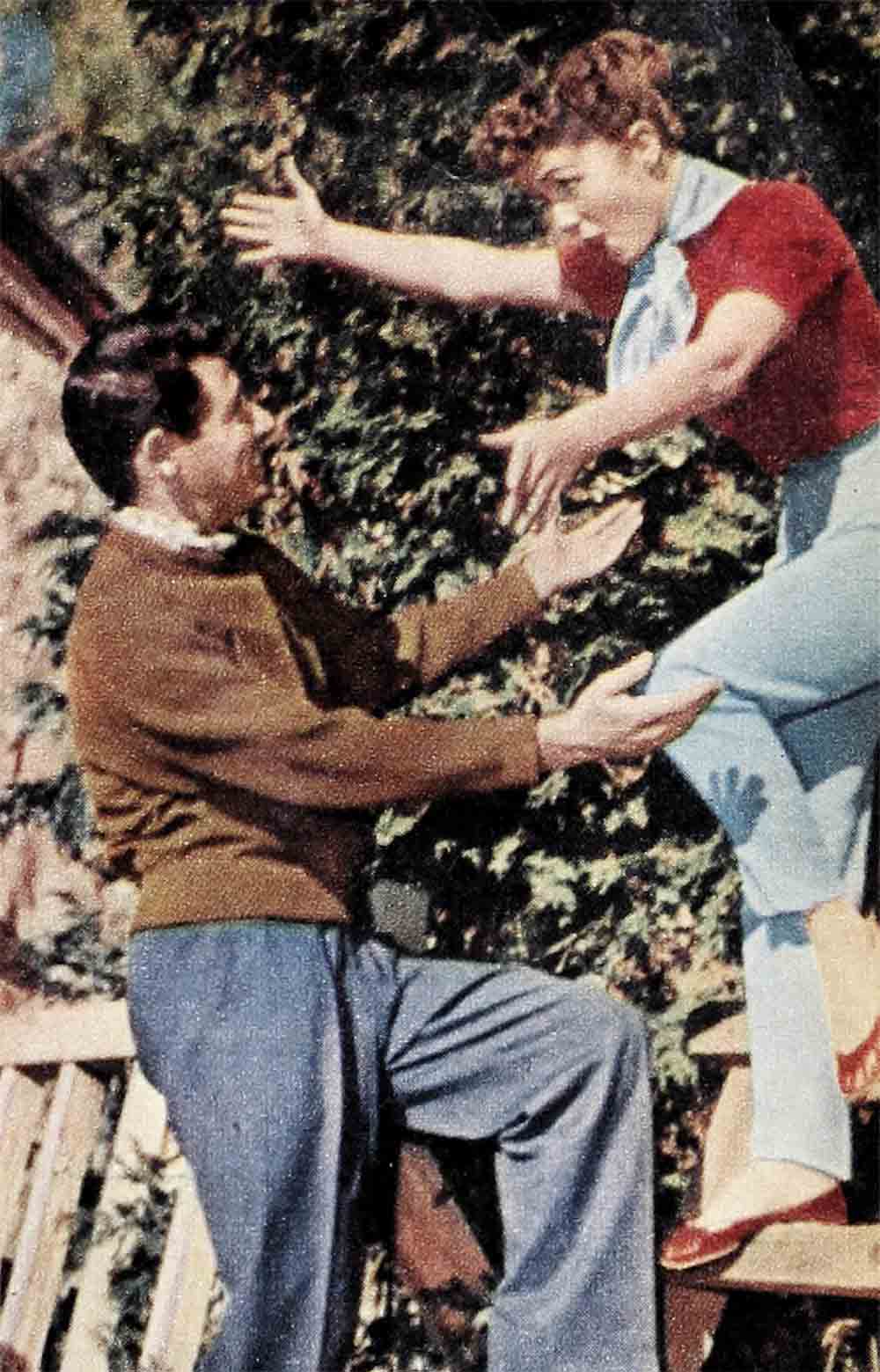

Whenever their schedules permit, Debbie and Eddie love to perform together. Eddie often reads lines with her at home now.

“I’ve played Bette Davis, Barry Fitzgerald, Ernest Borgnine, and I’ve even played Debbie,” he grins.

And whenever Debbie and Eddie appear together before the public they really stir up a storm. “We haven’t any special material. We’ve never worked up anything really. We just clown around and sing and have fun,” he says. Not long ago, when Debbie accompanied him to San Francisco for an appearance, they were mobbed. As usual, Eddie called her on stage from out of the audience. They sang “Love and Marriage” and Debbie removed her shoes and ad-libbed a little dance for them. As they were going off, the fans rushed onto the stage en masse. “Shoes—they had them,” Eddie recalls laughingly.

They’ve proved how wrong the prophets were who predicted marriage would lessen their popularity. They’re the hottest talents in show business today, these two. Debbie’s first dramatic role in “The Catered Affair” has opened a whole new field in motion pictures for her. Eddie has a contract with NBC for a reputed twelve million dollars of which he says, “I don’t know anything about the money. All I know, it’s for fifteen years.”

All he knows. He just follows the music wherever it leads, knowing it will always begin and end with a girl named Debbie and their own lifetime contract.

The sounds of the music were catching up with Eddie Fisher again now. The sounds of show time, the voices, the music, the fan sounds of success. But he wasn’t hearing them. He was thinking ahead, about the future. Originally, he and Debbie were scheduled to co-star in RKO’s “Bundle of Joy,” starting work in July. Then came the news that they could expect their own “bundle of joy” in November. Although this meant postponing the picture, Mr. and Mrs. Fisher couldn’t be happier. As Eddie has said before about their having children. “The right time is anytime.”

Then, too, there were other movie plans in the works for Eddie. One includes James Michener’s “Sayonara” at Warner Brothers in the very dramatic plum part of Sergeant Kelly, the GI who falls in love with a Japanese girl.

“I’ve had my eye on this part for some time. Josh Logan’s going to direct and Irving Berlin’s going to do the music. It will have songs in it. I couldn’t do it unless it had songs—something to hang on to,” Eddie was saying modestly.

With Eddie so active in motion pictures, Hollywood will be home base much of the time for the Fishers and there will be fewer conflicts in their two careers. However, together, all time and space is relative anyway.

In a few hours, they would be in the air again. Eddie would be recording until plane time, and Debbie would be taking to the skies with him determined not to let anything ever separate them—physically, contractually or geographically.

“Home” for them can be a house in Hollywood . . . an apartment in New York . . . a plane commuting through the clouds . . . Or any strange hotel room. For home is where the heart is, and for Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher, wherever they are is home.

THE END

—BY MAXINE ARNOLD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1956