Bing – Goes That Crosby Myth!

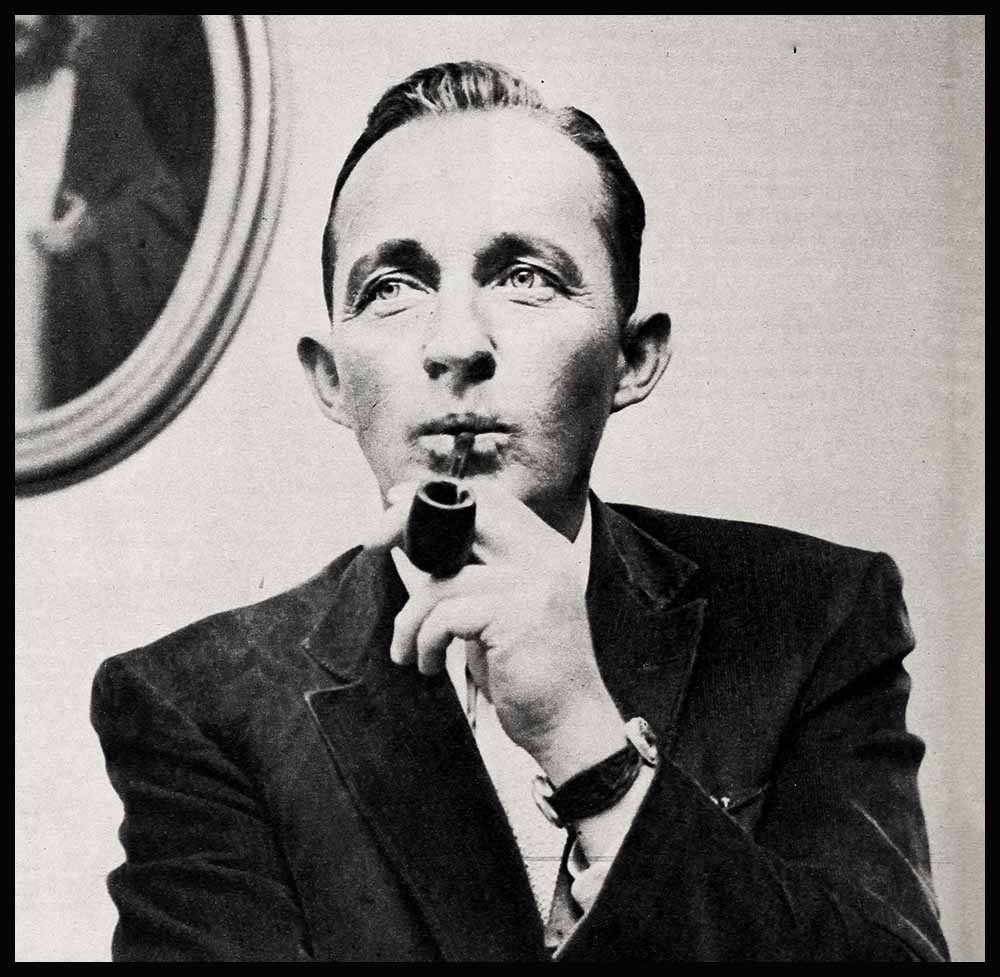

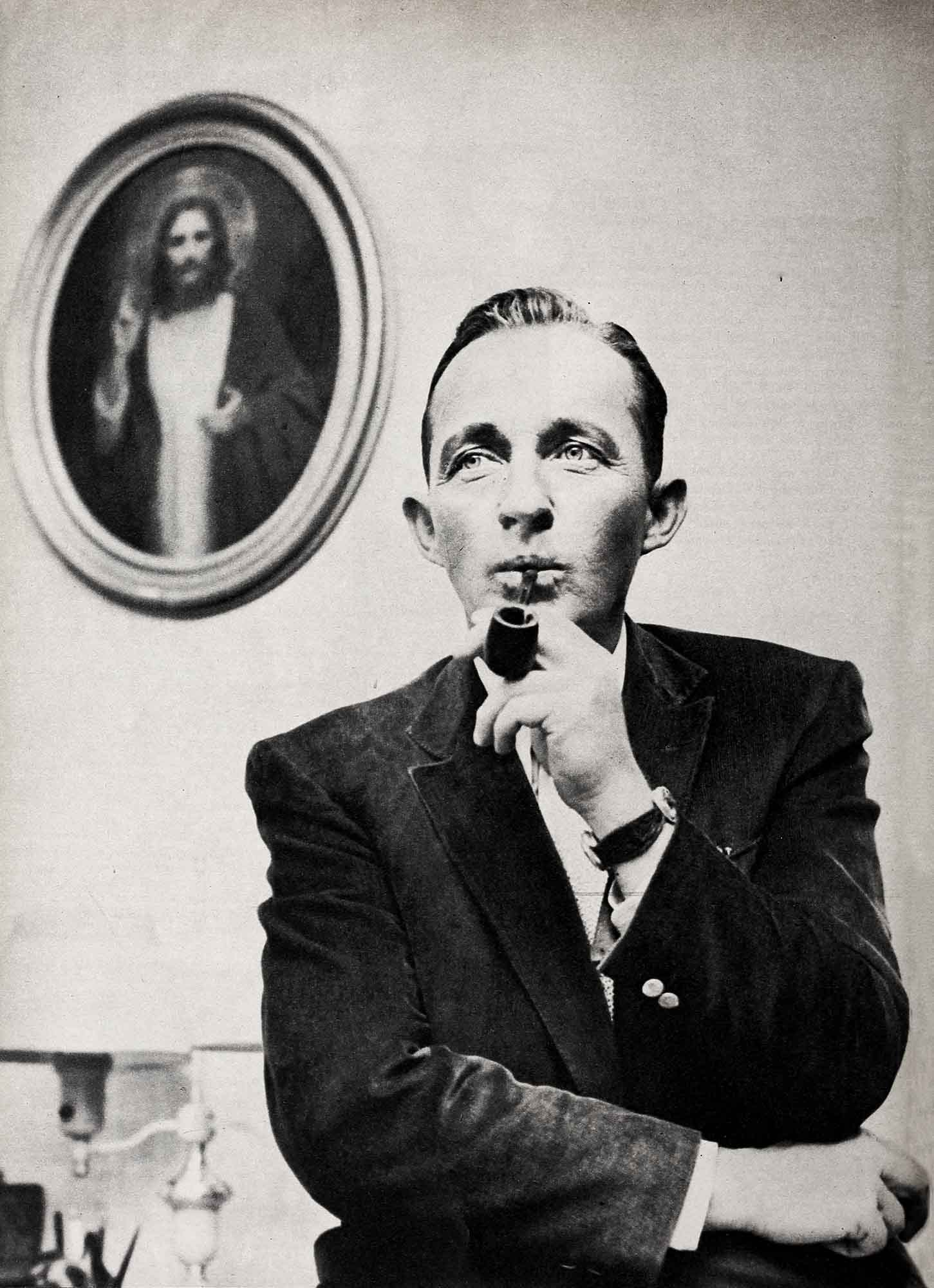

Everybody knew Bing Crosby. At least we thought we did. We all believed in the comfortable myth of the casual crooner with the bland blue eyes, the inhibited horses and the uninhibited shirts. Why, he was about the most familiar personality in the world, the nonchalant fellow whose rhythm for living was set to the easy swing of a golf club or the wigwagging of an itchy foot following the beat.

Bing was simply giving his best performance off-screen. underplaying himself. Probably, he would have liked to go right on hiding safely behind the great Crosby myth. But it’s too late now, and that’s his own fault. He has turned himself inside out for the whole world to see, revealing a man with rare emotional depth and sensitivity, with almost incredible strength.

The revelation began one night, in a projection room on an otherwise deserted studio lot, while a rough cut of “The Country Girl” was being shown to a very chosen few. Among these was a fellow artist of Bing’s, his oldest son. When the lights came on at the end, there was a loud hush. Everybody sat there without a word. Finally, near tears with admiration and the emotional impact of the picture, Gary Crosby said, “I . . . I didn’t know Dad could do that.”

His dad hadn’t known it, either, any more than the rest of us—except for the close friends of many years, who could always see behind the myth. William Perlberg, producer of “The Country Girl,” says, “Bing’s emotions are hidden deep inside. But these are the people who have the most. The fellow who wears his heart on his sleeve is usually lacking in heart.”

Bing could hardly have foreseen the far-reaching personal effect of that offbeat role. George Seaton, director of the film, recalls, “Quite a lot of pressure was put on him not to play the part. After all, he’d made tremendous strides in the business already. He’d taken every character and made it into his own image—the most enchanting personality the screen has ever known. With a huge following like Bing’s, he could have stayed in the same groove forever. But he didn’t. It took plenty of courage to jump into something like ‘Country Girl.’ ”

Actually, challenge has always been Bing’s meat. There never was any such person as the easygoing character of the Crosby legend. As a kid, back in Spokane, he smothered the opposition in an elocution contest with a spirited delivery of “Horatius at the Bridge.” One summer, against odds and a lot of brotherly hoots, he entered the city swimming meet against champs who’d all had special training. Young Harry Lillis Crosby came home late that evening tired but triumphant—with eleven medals in his wet, hot hand.

The “lazy” Crosby believes firmly in the character-building value of sports. Years ago, this reporter (then working for the home-town paper) was rounding up stars’ advice to young hopefuls Hollywood bound. Pursued to the Lakeside Golf Club, Bing came out of the golf shop whistling, posed genially for the Brownie and gave this advice to kids: “Excel in some kind of sport.” Shouldn’t they learn to sing? No, said Bing good-humoredly (a very patient man). Make a name in sports and you’d be in anywhere. More important, you’d acquire a spirit of good sportsmanship, an ability to face competition, a will to win that would help you find success in any field.

For all his offhanded manner, Bing has a solid sense of integrity; merely winning isn’t enough. On the wall of his dad’s old office, next to Bing’s own, are the framed words: When the One Great Scorer comes to write against your name—He marks not that you won or lost—but how you played the game.” Pop’s gone now, but Bing still treasures the words he loved.

Twenty-five years ago, when Bing was hardly known as one of the most responsible characters in show business, William Perlberg saw through the carefree air. Bing was one of Paul Whiteman’s Rhythm Boys, a boy in a striped blazer, with a captivating croon and an ingratiating way with the ladies. Then an agent, Perlberg was impressed by “an unusual attractiveness about his personality. As a young man, he had a tremendous, warm appeal, which has naturally increased in stature through the years.”

Heading back to Hollywood from a very unprofitable tour, Bing wrote his agent a letter including these plaintive remarks: “It has occurred to me you may possibly be able to line up a couple of parties—giving us some work until something more definite pops. Marion Davies or some other . . . ”

Perlberg booked the singing trio into Eddie Brandstatter’s Montmartre, then Hollywood’s smartest cafe. Soon afterwards, Bing got an offer from the Cocoanut Grove. Promptly, he told Perlberg: “There’s only one thing—the deal says we can’t have an agent. So I told them I won’t take it!”

Perlberg released Bing for the new offer by tearing up, with a cavalier and costly twist of the wrist, what turned out to be at least a $10,000,000 contract. Agent and crooner finally were reunited as producer and star. The profound loyalty of Bing’s true nature brings him the same loyalty in return. Perlberg’s a twenty-five-year man on the Crosby team. Among the twenty-year men have been: Wally Westmore, make-up man; the late Barney Dean, gag-man; Jimmy Cottrell, propman; Leo Lynn, Bing’s Man Friday and good right arm. Wally says, “You don’t kid Bing. He’s death on backslappers and yes men. And he can spot a phony a hundred yards away.”

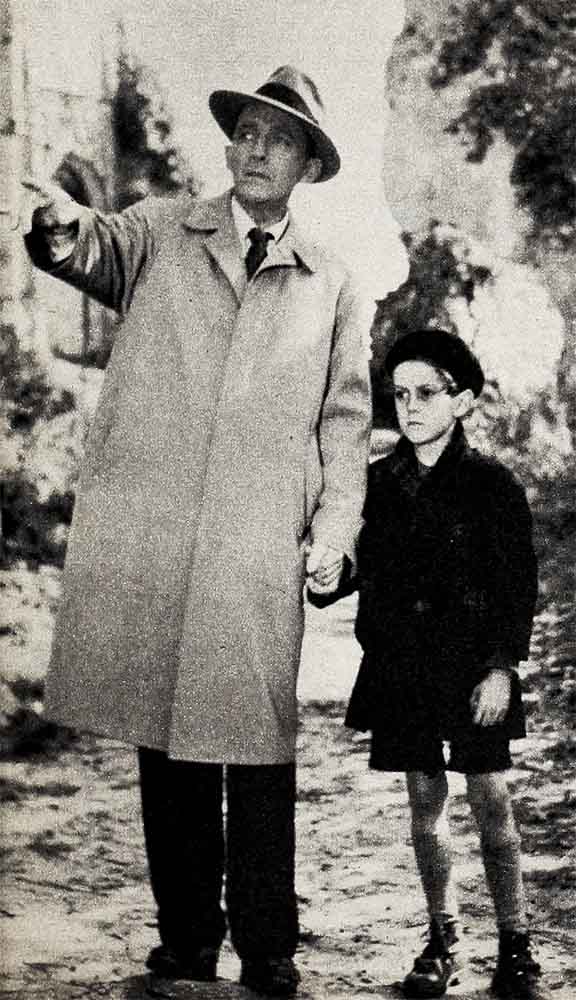

There have been times when Bing has needed the devotion he has so truly earned. He took on his first serious dramatic performance, in “Little Boy Lost,” when Dixie was gravely ill. He sailed away to France on location—on her doctor’s orders. “She knows you’ve planned to go,” the doctor explained. “If you stay behind, she’ll know why. And that would do it.” Through long weeks overseas, Bing never disclosed the truth to anybody; he carried the whole load himself. He was quieter than usual. Almost every other day, he called Dixie on the transatlantic phone. Evenings, he holed up in his hotel room, working on his autobiography.

But his good friends sensed his trouble. “We were all groping around for some way to help,” one of them recalls. “Tryping out how far we could go—maybe pulling a little gag. And Barney Dean—I’ve never seen a man stick so near.”

A funny, endearing little man, Barney was a bit out of his league on “Little Boy Lost.” There were no laughs needed for that picture, but Barney worked harder than he’d ever worked in his life to provide one. At intervals he’d go around staring thoughtfully at the ceiling of the sound stage. If interrupted, he’d chide gently, “Don’t bother me now—I’m thinking up drama.”

The tragic news finally came, Three days after Dixie was gone, Bing was back on the set, welcoming the distraction of work. Both Bing and director George Seaton believe in shooting a picture in continuity, to sustain the characterizations. By a sad irony, the next scene called for Bing, as a war correspondent, to broadcast the news of his wife’s death. “This man,” Seaton says, “can feel an audience better than anybody—and he felt all the depressed reverence around him. And he soon let everybody know, ‘We can’t go on this way.’ ”

Seaton decided to approach the problem forthrightly. “Look, Bing, I can’t avoid the lines here in the script—speaking about a wife who’s dead. But we can change the shooting sequence, any way you want to handle it.”

“I understand,” Bing told him. “Nothing you say or don’t choose to say is going to change matters. Let’s make a picture!”

Taking their cue from Bing, saying nothing, they all rallied around him, helping. Even the “little boy lost,” Christine Fourcade, was always clinging to him, walking hand in hand with him, haunting eyes ever watching him. “He idolized Bing,” a friend remembers. “He would unconsciously imitate him. We could hear them laughing together sometimes—and that was a very good sound.”

Eventually, Bing had to face an even more grueling scene, the most important in the picture. The war correspondent, who had never in his own heart accepted the fact that his wife was dead, would be forced to listen to the official, brutal account of her death, read by a friend. He had to realize that to go on living and to love the living a man must bury his dead.

“Bing,” Seaton explained, “you’ve got to let yourself go in this scene. You can’t be holding back. You’ve got to make the audience understand how you feel here—how it’s going to be.”

“You’re talking about any actor. I’m a crooner.”

“Not in my book, you’re not.”

When the camera stopped turning, Seaton came up to Crosby. “You had tears in your eyes.”

“I did not,” Bing said.

“You’ll see.”

They ran the rushes. “If that’s a crooner,” Seaton said quietly, “then I don’t want actors.”

That may have been the first time that Bing fully revealed himself before the cameras. But there was an earlier occasion when, far from Hollywood, he unconsciously let others look into the depths unsuspected during his crooner days. He was touring the muddy battlefronts of France, entertaining the weary troops of the Third Army, trying vainly to duck the always-requested “White Christmas.” Bing sang for the boys in the “hopeless tents” with all his heart—and with the prayer that his eyes weren’t giving him away Afterwards he said to a fellow member of his troupe, a little dazedly, “You know—I don’t even remember doing that show. Did I do okay?”

This was the Bing Crosby that Seaton wanted to capture on film. The director still insists, “The scene was one of the finest moments I’ve ever seen on the screen. Bing’s one of the most talented men this industry has ever known. He has a tremendous wealth of talent as an actor, which hasn’t been tapped until recently. He’s also one of the most intelligent human beings I’ve ever run into. In my opinion, he can play any part Spencer Tracy can play—any part that requires real soul-searching. I knew he could do ‘Country Girl.’ ”

Convincing Bing that he could do it wasn’t so easy. From the beginning, producer Perlberg and director Seaton had only one actor in mind for Frank Elgin, the irresponsible has-been, the pathetic alcoholic, the psychopathic liar of “The Country Girl.” It wasn’t fear of the critics that made Bing hesitate. As he’s said, “I’ve been impaled before.” He just didn’t believe he was actor enough. “I don’t think I can cut it,” he said. And he returned to his old refrain: “You need an actor. I’m a crooner. You need a Fredric March or somebody like that. I just don’t think I’m capable.”

“Have a little faith in us,” they told him.

“Well . . .” he said finally. “I’d love to do something like this. If you guys think I can do it—I’m in your hands. I’ll do anything you ask me to do.”

As soon as actual work began, Bing’s doubts lessened. “Actually,” he says now, “it turned out to be a very easy picture for me—the easiest I’ve ever made. It was well-prepared; we rehearsed in advance for ten days. Everything was so well coordinated we even finished the picture a week early. George had a good tight script— and the script we had at the end of the picture was the same one we started out with. That’s different from big musicals— they can get pretty confusing. You try to improve on the script as you shoot. You labor and sweat, and you’re all slowed down. I’m not an authority on this, but I think a great script plays an actor’s part for him.”

Bing’s as generous with tributes to his co-stars as to his director. “Working with Holden . . . well, he paces you. He really brings you up. In a fast league like that, you’ve got to pick up the pace.”

Throughout shooting, Bing knew that he was working as part of a team—including the whole crew. When the cameras stopped rolling one day, Chico, the assistant director, had some announcements to make. On behalf of the crew, he handed out plaques as tokens of appreciation. The one presented to Bing said: “This plaque is with deep affection from the entire crew—so please take good care of it. It cost us a pretty penny.”

Seeing these words, Bing stammered, “I think this—is the nicest gift—I—have ever received.” And he turned away fast—but not quite fast enough. Not before they saw him misting up.

“That El Bingo!” Chico says. “I’ve never seen a man who was so much so overcome by such a small thing.”

In spite of these reassurances, Bing (he admits now) kept on worrying after shooting ended. He’d been all primed to be a poor man’s Barrymore, and he was afraid he hadn’t put enough emotion into the role. He had his regrets about that memorable jail scene in which Elgin, with a bad case of the shakes, breaks down and cries. “I didn’t think I did enough. I could have gone more. I was ready to really tear up the scenery.”

Bing’s son Gary reacts to that self-criticism with a startled laugh. “The next step would have been seeing elephants, so I’m told. That drunk scene in jail—that killed me! I couldn’t believe it. I wasn’t home while they were shooting it, but I hear that Dad stayed up all the night before, drinking stale coffee and letting his beard grow. I thought he was great!”

Such an earnest approach to a difficult part certainly wouldn’t fit in with the old Crosby myth. But it’s typical of Bing himself, and it took its toll in nervous energy. Afterwards, he went to Hayden Lake, Idaho, to rest. There an unexpected crisis confronted him, in the shape of a long-distance call from a doctor who had just examined Bing’s old friend Barney Dean. Prompt surgery was imperative. Bing contacted his own personal surgeon (the finest), who was out of town but flew home. There was never a chance; in three days, Barney was gone. Gag-man to the last, even in the hospital, he’d given Bob Hope a line that was a classic, printed throughout the land. ‘What do you want me to tell Jolson?’: he asked.

Bing, too, had talked with Barney, from Idaho. But, under the stress of his emotion, the whole thing was such a haze for him that he can’t even remember what was said. He’d said since, “It was a pretty difficult conversation—all the way.”

It was a selfless grief that confused Bing—not the fact that he himself was facing surgery at the time. He’d been undergoing treatment all through the shooting of “Country Girl,” with the hope of staving off an operation. He treated the prospect so casually that his friends were surprised at the final tip-off Says one of them, “When Bing charters a plane and flies away from a golf tournament—he’s sick!”

In the hospital, Bing refused to play the invalid. Before the operation, he found he’d be short some CBS radio shows; so he told producer Murdo McKenzie (a twenty-year Crosby man in radio) to bring the tape recorder to his room at St. John’s— “And we’ll cut a few before we go.” Who hut Crosby, before going into surgery, could chat so easily into the recorder about the French switching to milk, about the noble art of truffle-snuffling?

More than that, he kept up his fabulous correspondence from his hospital bed and even maintained a clipping service for a few friends. Rosemary Carroll, his secretary, called Jimmy Van Heusen with this message: “Mr. Crosby’s sending over some clippings from Australian papers for Frank Sinatra. They’re about his tour. He thought Mr. Sinatra might like to have them.”

No wonder Van Heusen says, “Bing’s a very big man. Everything s big about him. There’s his correspondence—no man writes more letters than, Bing. And his silent charities, his mentality, his huge memory. He’s a wonderful father. And he can bear pain better than any man I’ve ever known.”

From the hospital room went clippings to George Seaton, too—hinterland-newspaper reviews of “Country Girl” that Bing thought the director might otherwise miss. But every time a critic made flattering mention of Crosby, there was a Crosby footnote: “Of course, he’s really talking about you.”

Bing was recuperating at home when the Academy Award nominations were announced on television. He watched the show with sons Gary and Linny and with Jimmy Van Heusen. Innately humble as Bing is, he is also too honest to have pretended surprise. “Well,” he says, “I thought we might have a chance. I was very gratified. I’m happy we got a movie. But you never know. I thought we had a chance with ‘Little Boy Lost’—with the picture, that is—and we didn’t get in.”

Nobody was pulling harder for Crosby to win than his sons were, and nobody sensed more deeply how much it would mean to him this time. Linny showed a bit of the inherited casual air when he offered congratulations on Bing’s radio show, saying, “It really thrilled me, Dad—and may I say it hasn’t hurt me socially, either.”

And Gary says, “I thought Dad was good in ‘Going My Way,’ but he was still himself. I don’t think he thought too much of his own performance. I know he’s always said about winning that award, ‘Well—it was a war year,’ But ‘Country Girl’ really amazed me. It was so different from the carefree bit in the ‘Road’ pictures and all that. ‘Little Boy Lost’ was the warm-up—but this was the big show. Disregarding the fact that he’s my father—and being as objective as I can—I think Dad gave the best performance last year. I wish I’d had a vote. I’d sure have given it to him.”

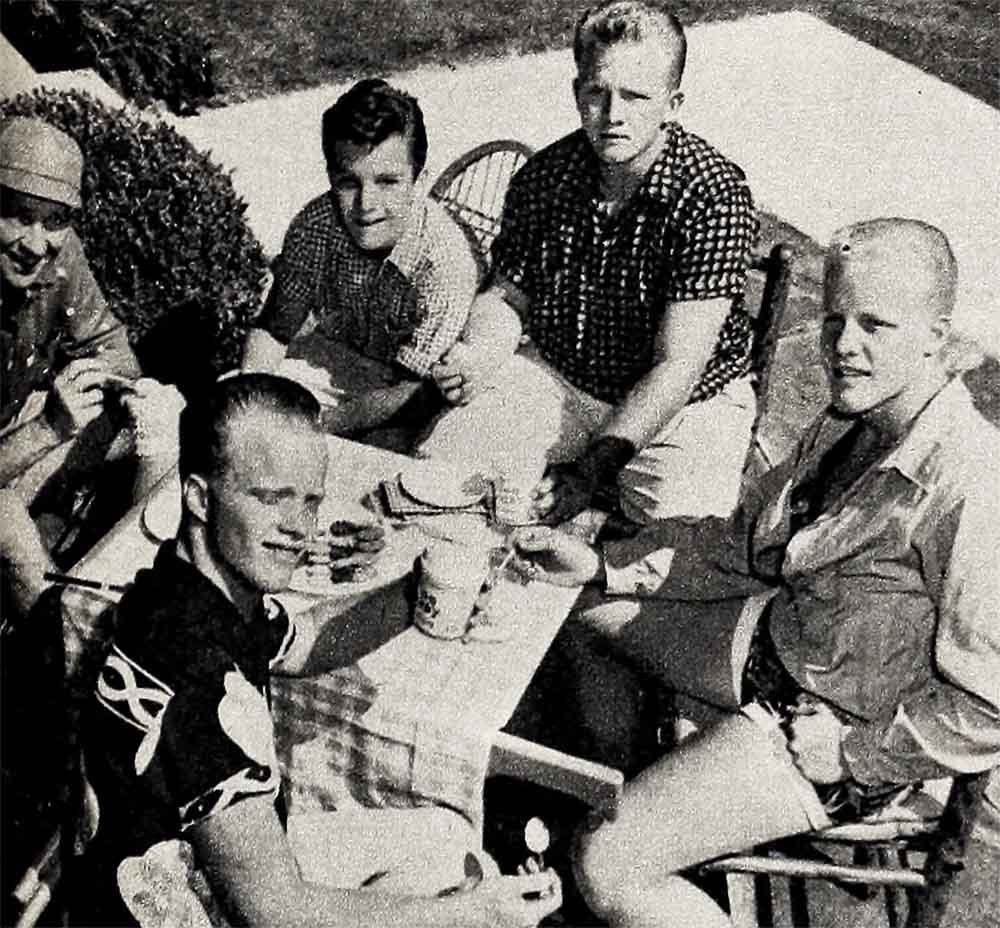

The devotion that Bing’s sons feel for him is a natural return for the affection he has lavished on them all their lives. In his studio dressing room and his office, the story’s there for any visitor to see. Except for pictures of Dixie and his mother and his horses and himself (hoisting his biggest fish), the walls are papered with photos of the boys at every age and on just about every imaginable occasion.

But it’s well-known that Bing can be a firm disciplinarian, too, and that he has done his best to keep his fame from interfering with his sons’ lives. At school shindigs, he always tried hard to remain in the background. When photographers closed in on him, he would protest, “Look—I’ve got nothing to do with this. I’m just here like any other father. This isn’t my show.” An important magazine once tried to high-pressure him with the reminder of all they could do for Gary. That’s exactly what I don’t want,” he told them emphatically. “I want Gary to be just like any other normal kid going through school. These things make it very hard for him.”

Consistently, Bing has shown strong parental interest in his sons’ grades at school —and in seeing that they kept the nightly curfews at home. They admit to having been “grounded” on occasion in the past. for periods varying with “the gravity of the offense,” and at the time each probably felt a boy’s natural resentment. They understand now. As Gary says “He’s no spare-the-rod-and-spoil-the-child father, but any time I ever got a licking I had it coming. I’m happy I was brought up that way, rather than the spoiled and pampered deal. That would have made it a whole lot tougher later on—like now, with the show ahead of me.”

Gary’s heart has always been in show business, set to the same beat that impelled his dad toward Hollywood. The public discovered Gary when he sang “Dear Hearts and Gentle People” on the Crosby show five years ago. At the general reaction, a forecast of Gary’s future, Bing certainly felt fatherly pride. But mixed with it was some measure of fatherly fear over the effect this might have on the school years ahead and the sort of future Gary’s parents wanted for him.

It’s typical of Bing that, once he realized there were no sheepskins in sight, he let Gary set his own course. Without making a production of it, Bing gave: his son his own time slot last summer and backed him up with his own trusty radio crew. It’s typical, too, that he had one parental admonition before Gary took off. “Keep it in good taste,” he said.

Ask Gary whether, as a newcomer in show business, he has any kicks about being Bing’s boy. You’ll get: “Kicks??? I’d be out of my mind! Sure, some people want to compare me with Dad—but I could be compared with a lot worse. Nobody’s got a voice like his, and in thirty years nobody’s ever been able to cultivate one. I don’t mean to say it’s all roses,” Gary adds conscientiously. “There are a few thorns. There are always some wiseacres who give you that routine about being just ‘Bing Crosby’s son.’ But the roses sure choke out the thorns. I’d never have gotten that break last summer—having my own show—if it hadn’t been for him.”

Now Bing is taking more than a casual interest in his son’s career. “Gary never did much in show business until last year, he says. “A few radio shots. A few records. He’s had no experience with the public or working in front of people. He didn’t start out in radio with the experience that I had or that Sinatra or any of the rest of us had—a ten-year stretch in vaudeville or night clubs or with bands. He broke in with practically no experience at all. It was quite a jump for him—maybe too much. But he’s getting under way now.” After appearances on Tennessee Ernie’s show beginning in March, Gary again gets his own show this summer, and CBS plans for him also include guest shots on TV.

As the oldest boy, Gary has naturally been in the public eye more than his brothers. But Bing’s fatherly heart makes no such differentiation among his four sons. The twins are in the service, and Bing keeps the warm newsy letters rolling toward them, along with batches of oatmeal cookies. “The kids like to get them from home. Phil’s still taking basic training at Fort Ord. Denny’s finishing his basic at Fort Riley, Kansas, and he’s going into G-2—Military Intelligence. lf he shows any aptitude for that, he’ll be going to Germany this summer.”

Dark-eyed Linny, affectionately dubbed The Boy Genius by his brothers, is attending Loyola. His plans shift daily between being an artist and being a baseball player and studying for the priesthood. As the baby of the family, he still has a curfew to observe “He’s supposed to start turning in by nine P.M. during the school week,” his dad grins, “but it usually takes him a little longer to get going.”

A fair rhythm and blues man, Linny frequently guests on his father’s radio show, sometimes singing, sometimes plugging “client” Gary’s Decca records, like “Koko-Mo.” Linny’s picked up quite a following of his own, and the Australian-American romantic exploitation that Sinatra gave him didn’t hurt his international social standing. A little-girl fan of Lin’s, who’d seen him with his father on Ed Murrow’s “Person to Person” show, recently wrote requesting a picture of the two Crosbys. Bing finally found one shot, a candid flashed during rehearsal, but he figured it didn’t flatter him. “Not very good,” he said doubtfully.

“Not bad of me, Dad,” his son said significantly.

During the past two years, since the boys’ mother died, Bing has had to carry a double burden of responsibility in their upbringing, and at times it weighs heavily. “The toughest thing about it,” he says, “is trying to combat the wrong advice they get. It’s tough trying to beat down all the advice from people conning them, telling them how lucky they are, telling them they should go to New York, telling them how great they are. We’ve always kept the boys on a pretty even keel at home. But there are so many people around here—mostly people who’ve messed up their own lives—who are always ready to give a kid bad advice.”

By contrast, here’s what Bing wants for his sons in the years ahead: “I’d just like for them to do something I can be proud of—something they can be proud of. Have ‘class,’ be good citizens, raise families, do something worthwhile in the world—whether it’s in Science or athletics or whatever. I don’t care what it is—but have a goal of some kind and get there, not as Bing Crosby’s kids but as themselves. I know they’re living in the shadow of something built up. But they have all the equipment to overcome this.”

About his own future, Bing naturally has more definite ideas: “I’m getting along now to a time of life when it doesn’t look too attractive for me to always be chasing up and down ‘Roads’ or be arch or coy. I don’t plan to try to be a great actor or anything, but I do want to do more sensible things. ‘You’re the Top’ is a big, gay musical, but I play a more settled character. I’d like to do a good comedy like ‘Genevieve’ or ‘It Happened One Night.’ And next I’d like to find a simple, sentimental story with a kid or with a juvenile-delinquency theme. A good, tight story—maybe without songs. They can take away from the credibility.”

You may wonder: Where can Bing go from here? No matter what he does, how can he top himself?

“Oh, I don’t think I’ll done anything exciting,” he laughs. “I’ll just been plugging along . . .”

And typical of Bing’s modest attitude is what he said before the Academy Award’s presentation: “As far as my winning the Oscar is concerned, I don’t see how a performance such as mine can win over Brando, in ‘Waterfront.’ ”

But he can’t get away with such modesty now. It’s too late. Nobody believes any longer in the good-natured drifter cruising aimlessly along. Bing himself has always maintained, “Every man is the result of that which happens when his life touches the lives of others.” He means this as a tribute to those who have helped him when their paths crossed his. But he’s stuck with his own words, for Bing Crosby intimately touches more lives than any other human being in the world today. The music he makes—whether in the key of hope or harmony or laughter or charity—is his own unique Oscar, taller than any of the Academy’s golden statues.

Bing’s real beat comes everlastingly from the heart and not just from that rhythm-happy foot. Whether he likes it or not, folks all over the world are wising up to the truth about him, and he’ll never live it down.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1955