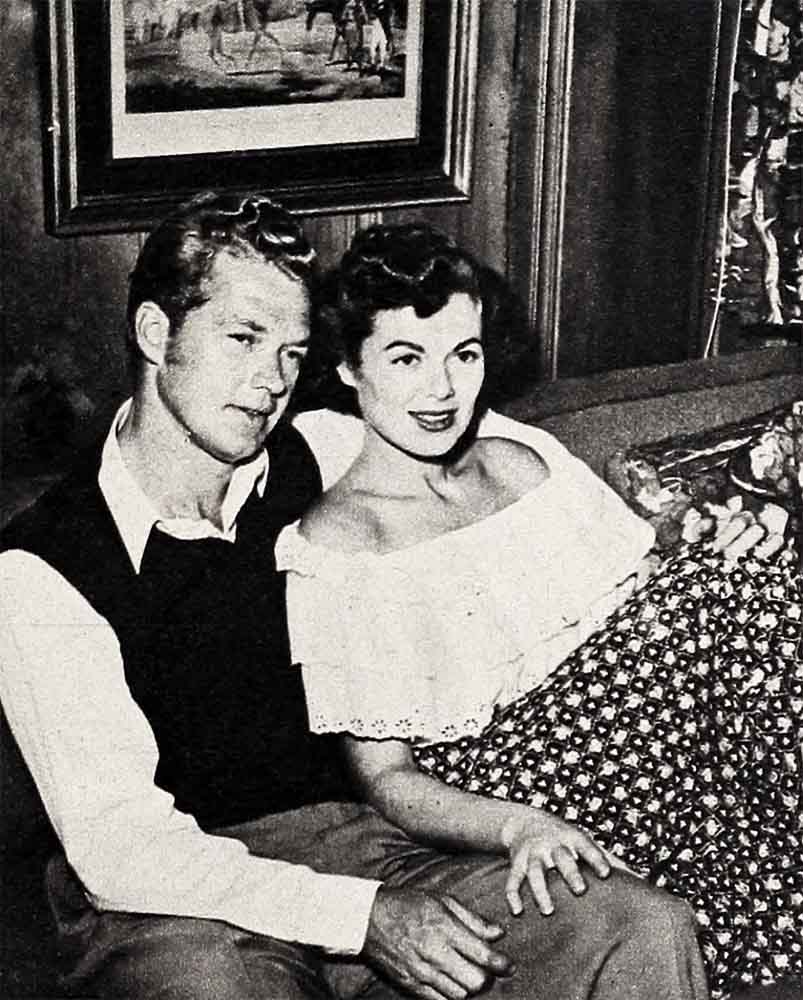

No One Else Could Take Her Place

You wouldn’t know it to look at us now. Things couldn’t be rosier. The little woman, that’s my wife Barbara Hale, a big sensation in “Jolson Sings Again”; the old man, that’s me, working steady; everything in our little house in the Valley, including our two-year-old daughter Jody, paid for and ours free and clear.

But it was very rough for the newlywed Bill Williamses a couple of springs ago, and I think even my redoubtable wife will admit it, now. If we never have to go through anything like that again, believe me, it will be all right with us.

It was a good thing, two years ago, that we had our love to keep us warm.

AUDIO BOOK

To begin with, we were both out of work, and the savings account we had started so hopefully was beginning to look anemic. We had felt very rich when we got married, the June before, and why not? We were both under contract to RKO, and both of us had just had an option lift and a nice raise. Not only did we feel rich enough to get married; We wanted a baby, and we bought a little house.

Then our studio ran through three administrations and everybody, including us, got fired.

Barbara refused to worry. At least, she refused to admit she was worried. Lots of people had had babies, she said, with a lot less security than we had.

But I fretted. I was a slum kid. My father died when I was six years old, and my mother worked like a dog as a waitress to pay a couple to take care of me, you could hardly call it room and board, because I slept in the bathtub, but they were kind to me, and it was home. I could remember, all too vividly, what it was like to be broke, really broke. I felt the pressure all the more deeply, I think, because I knew Barbara didn’t know what real poverty was like, and I didn’t want her ever to have to face it.

I had met her folks, and all her nice friends, when we went back to her home town of Rockford, Illinois, to be married. That pretty little mid-western city, that sense of roots and matter-of-fact abundance was a far cry from the struggle just to stay alive I remembered from my childhood.

Barbara probably can’t understand this even yet, and she is the most understanding, the most generous, and the most patient and tolerant person I’ve ever known. But I worried until I was sick.

And then one morning I was really sick.

I’m a big guy, and I look like a healthy brute, but I have an old back injury which goes back to my adagio-dancing days. It kicked up when I was in basic training in the service, and I was medically discharged.

It had let me alone for a couple of years. We didn’t need my trick back cutting up on top of everything else, but we got it. I went to bed one night, feeling fine. The next morning, I couldn’t get out of bed. I couldn’t move my legs.

This business went on for five interminable months, and I don’t think Barbara said one discouraged word. When it began to look as though one doctor couldn’t lick it, the poisoning, or infection, or whatever it was, Barbara would dig up another specialist. We didn’t talk about it, as though by mutual consent, but I know I dreamed about doctor bills.

The topper came when yet another doctor decided that I should go into the hospital for a concentrated series of penicillin injections.

Barbara drove me down to the hospital, I was on crutches, and she was carrying my bag. The elevator operator took one look at Barbara, the baby was just a month off by now, and deposited us on the maternity floor!

I wouldn’t have given a dime right then for my chances ever to get well, ever to get back to work, ever to be able again to take care of my family. And I’m an old-fashioned guy. In my book, a man isn’t a man, unless he’s a breadwinner.

Despite everything Barbara had done, and she was magnificent, the most wonderful support in time of trouble a man ever had, I felt I was washed up. I had lost all confidence. I was ready to give up.

I don’t know exactly what turned the tide. The penicillin worked, for one thing. And I know that first look at our precious little Jody helped. It helped when I heard Barbara’s voice, happy and alive, on the loud-speaker in the hospital waiting room.

“Tell my husband to come up.”

New hope ran like new blood in my veins when I heard that.

And then I got a job in “The Stratton Story.” A job, as a free-lance actor, at twice my old contract salary. That helped. And how!

Funny. We can talk about it now. About how rocky things were. While it was going on, we would talk about everything else.

People say our marriage must be strong for the ordeal, but I can’t feel that way about it. Barbara and I didn’t need to go through the torments of the damned to know how much we mean to one another.

It was inevitable from the day that we met, when we were both just breaking into pictures at RKO, that we would be married. No matter how much we fought the idea, and both of us fought it, it had to be.

I had sworn early in my show business career, and I was a professional dancer when I was seventeen, that I’d find friends among the women, in what I thought was a rugged profession, but never a wife.

But they mixed, for Barbara and me, from the start. We met doing a publicity layout. Barbara needed to learn some swimming for a picture, and I taught her.

When we finally got a chance to make a picture together, we found all sorts of excuses to be together on and off the lot. We’d have coffee in the commissary and tell one another our troubles. We were both feeling pretty blue about the slowdown at the studio, we were never going to be actors, we figured, if we didn’t get our faces on the screen. I think the first item in our mutual attraction was our mutual need for a shoulder to cry on.

Barbara says she was just as determined as I was not to let this thing between us get serious. But I wonder.

And Barbara won’t admit this, but she wooed me. “You can drive me home tonight,” she’d say, or, “Wouldn’t you like to grab a bite to eat after we finish shooting. Dutch treat, of course.”

And on New Year’s Eve, she called me up and asked me to take her to a party. Somehow, in this process, my fine resolve about not mixing business and personal life was lost.

And then Barbara left town to do personal appearances, and I was desolate. We ran up a phone bill which could compare favorably with the national debt, and the day Barbara got back I was at the station a good hour before train time.

We spied one another at the same moment, and it was as though we were propelled by an unseen puppeteer. We landed in one another’s arms.

“Say, Bill,” Barbara said after a long moment, “How would it be if we share the same phone. The bills could all go to one address.”

That made it easy for me. The speech I had made up on the same subject was not necessary.

“That’s a deal,” I said. And it was.

It’s been a wonderful marriage except for, no, not except for, including that one spring.

We bought our little house and started fixing it up as soon as we got back from our wedding trip. We don’t go out much, and we don’t have many guests. We like being together so much better.

We’ve worked out this two-careers-in-one-family deal pretty well. When Barbara works, I take care of Jody, and cook, and shop, and run the vacuum cleaner. Why not? And when I work, Barbara does it. When we both work, and happily, it looks as though we’re going to have to adjust to that situation as normal, Barbara’s Mom, or a nice student girl who comes in sometimes, takes over.

As for that old bugaboo about who makes more money than whom, we don’t care. It all goes in the same bank account.

One thing that has helped our marriage as much as anything, I think, is that we never let an argument last overnight. We have our little disagreements, all people do, especially if they’re both working, and on the tired side. But we made a rule—and we’ve never broken it—in case of a quarrel, talk it out.

When Barbara went back east for the opening of “The Window,” already a celebrity, and set for one of those big studio build-ups, I went along for the ride.

The studio publicity folk met Barbara at the station. I got off the train to find my old dancing pals, Stew and Leta Morgan, waiting to greet me.

“I’ll see you at the hotel,” I yelled to Barbara as she was hurried away.

I stopped at the hotel desk a couple of hours later and asked for the key to our suite. “Mr. and Mrs. Bill Williams,” I said.

They had no reservation for the Williamses. “Maybe,” I said, temper rising, “it’s in the name of Barbara Hale.”

“We have a Barbara Hale registered,” the clerk said, suspiciously. “Do you know her?”

“I ought to,” I snapped at this, “she’s the mother of my child.”

This sort of thing happens, and it will go on happening. We expect that. And we don’t let it get us down, not for long, anyhow.

The grim spring is past, and will not come again. (We hope.) And the daily hurdles are not insurmountable.

We have our love to keep us warm.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1950

AUDIO BOOK