Patrick Wayne: “Should I Be An Actor Or A Priest?”

One night last fall the Glendale High School sports stadium was the scene of an unusual activity. The lights were on and an inter-high school football game was in progress. The players were striplings, but big, and were giving a passable account of themselves on the field. Under the lights they swung out of the huddles and into the line for the pass or the crushing charge for yardage with the precision and intensity of big-timers. The score was close enough for suspense—and the rivalry was earnest. But nobody was watching the field.

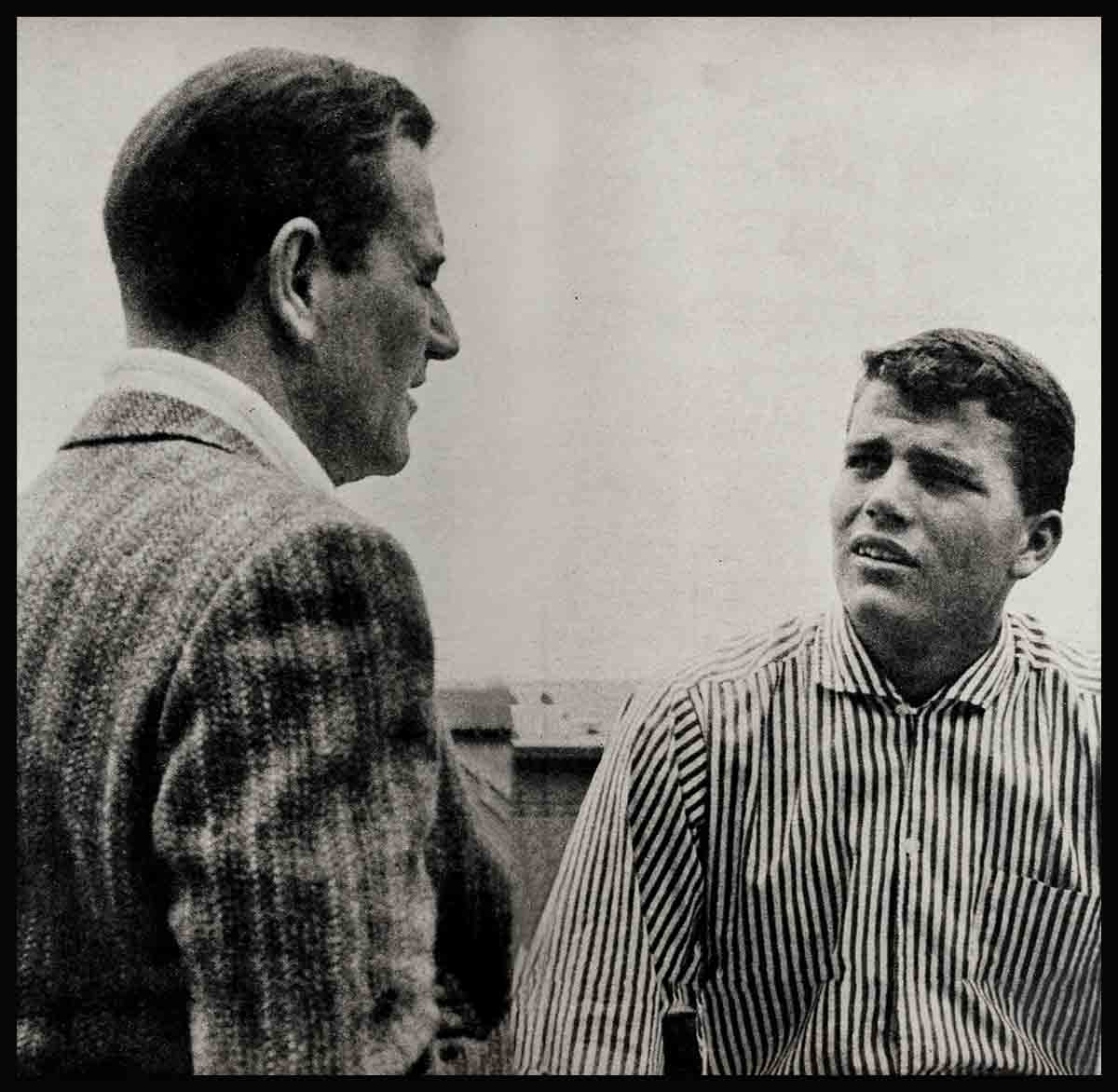

Half-way up in the stands on the fifty-yard line a big man sat hunched over in a hat and light top-coat munching peanuts. Beside him sat a petite, dark-haired woman in a mink coat. They had their eyes on the field, but everyone in the stadium had their eyes on them; and with disturbing regularity young and old fans alike shoved their way to the big man’s side and presented slips of paper to be signed. The man wasn’t hard to identify. He was John Wayne, a former graduate of Glendale High and now America’s number one movie star. The small woman was his wife.

Half-way through the second quarter, an Athletic Director who saw that the game was developing into a dismal flop because of audience distraction, struggled through the rows to Wayne’s side.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Wayne,” he said, “I know the fans must be bothering you. Would you like to sit some place else?”

“They’re not really bothering me,” Wayne said. “I love it. But I would like to see my kid play football.”

“Why don’t you come down and sit on the bench?” the A. D. said. “You’ll have a chance there.”

Wayne looked speculatively at his wife. The Athletic Director grinned.

“I never heard of a woman sitting on a bench at a football game before,” he said, “but this situation calls for a precedent. She can come, too.”

Wayne got to his feet, then halted. “I just thought of something,” he said. “I’m a Glendale grad—and my boy’s playing for Loyola. Which bench?”

“Take your pick,” smiled the A. D.

Wayne looked out on the field. The Loyola squad had taken a time-out and some of the lads were sitting on the ground while others were pacing about keeping limber. One of them stood about a head above the others. His name was Pat Wayne, and he was John’s sixteen-year-old son. He moved about slowly with the grace of a dancer. His shoulders were wide and his chest deep. He looked formidable.

“I’ll probably never be allowed in Glendale again,” Wayne said, “but I guess we’ll take Loyola.”

On the bench Duke and Pilar Wayne had rooting room, and the fans in the stands had no distractions, so the game went along as had been planned from that point on. But while the rest of the spectators followed the plays and the scores, John Wayne kept his eyes on his son. It wasn’t hard, because the boy stood out like an apple on a stalk of bananas. There was no waste in his movements, precision in his playing and courage.

The Loyola coach leaned over to Wayne. “The lad’s got it,” he said. “He’ll do well. What’s he going to do when he leaves school?”

“I don’t know,” said Wayne. “He’s got a mind of his own. But between us we’ll work it out.”

When the game was over, the kids stormed the field and Duke and his son signed autographs for about fifteen minutes. Then Wayne put his coat about Pat’s shoulders and they walked to the car. It had been a big night in Glendale—and a big night in the relationship between John Wayne and his son Pat.

The edge of a decision

Every man likes to have a son in his own image. John Wayne has four children, two sons and two daughters, and he has no inclination to favor one over the other. Michael, his eldest, has just finished college and wants to make his career the business end of motion pictures. Consequently, he is working for his dad’s company. He started at the top. The top of the list, that is, of fellows to call when the dirty work is to be done. Although he has been around movies all his life and knows the business pretty well, his father is determined that Mike will advance by the slow route—so he runs the mimeo machine and takes out the mail and runs the errands. He’ll get along, but the hard way.

Duke’s daughter Toni is married to a young graduate law student and Melinda, the baby of the family, is too busy growing up to be much of a problem. It is Pat, the one who resembles his dad-most, and the one on the edge of a decision, who requires the care right now, and he’s getting it for that reason alone. His father makes no pretense about wanting his son to follow in, his footsteps, but most of the decisions to date have been the boy’s.

When John Wayne and his first wife, Josephine, divorced more than ten years ago, because of a mutual incompatibility, it was a well-ordered separation, carefully arranged by two people who faced up to their responsibilities to their four children. It was agreed that the kids would live with their mother. That, accordingly to a prenuptial vow made by Wayne, they would be raised in the Catholic faith. And that in day-to-day living their mother would be their guide—but in major matters Wayne would take his proper place as head of the family. That is the way it has been.

Pat starts—at thirteen

Pat Wayne’s entry into motion pictures was quite a natural turn of events. His dad was a star and his Godfather was John Ford, the director. Whenever Wayne goes on a long vacation he tries to take at least one of the kids along—and when he goes on a distant location he either has the kids come for a visit or, if it is rugged, he has one or both of the boys come along and stay the full period. When he went to Ireland to make The Quiet Man it was Pat’s turn.

They were on the set one day when John Ford nudged Wayne. “I’ve been looking for a kid for the stuff we’re going to shoot tomorrow,” he said. “What do you think of that one over there?”

Wayne looked. Pat, tall for his thirteen years, was standing on a small hummock at the edge of the set dressed in blue jeans and etched against a blue, cloud-dotted sky. It was a fetching sight. He moved and it appeared that he was strung together loosely with wires. He kicked at a clod and there was a rhythm of grace as his foot went out and his blond wavy hair flew.

“I don’t know,” said Wayne. “It might get him into bad habits.”

“What’s the matter,” said Ford, “don’t you like this business?”

“Sure,” said Wayne, “but—”

“But what?”

“How do you know he can act?”

“Is that what you used to call what you were doing when I first met you?” Ford said.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” said Wayne.

Ford beckoned to Pat. “Come here, lad,” he said. Pat strolled over. “Go over to the wardrobe tent ‘and get yourself fixed up with something to wear tomorrow.”

“What for?” Pat said.

“You’re just like your father,” Ford snorted. “Always asking silly questions. Now get moving.”

And that is how Pat Wayne started acting in the movies. It wasn’t much of a part, to be sure, but by the next day’s end John Ford looked at the boy in a different light. Something like the way he had looked at his father twenty-five years before.

Spending money

Maybe it is true that you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink. But in the case of a young boy you can lead him anywhere and make him do anything if you pay him for it. The next summer vacation Pat Wayne began cozying up to John Ford like a cat after a milkman. Actors’ salaries are regulated by a union and it pays considerably better than mowing lawns. Ford found something for him, of course, and he did the same the following year. At first Duke Wayne took it in stride. This was just a way for the kid to pick up spending money. And then one day he looked more closely at the rushes. The boy had grown to a stalwart six feet. He had filled out and when he walked into the scene like a veteran. Duke leaned over to Ford in the dark.

“The kid’s pretty good,” he whispered. “And he can act!”

“It just goes to prove,” Ford muttered, “that talent isn’t hereditary.”

But acting in the movies was just fun and a pocket money business until one day in 1953 when John Ford dropped by Wayne’s house one evening, ostensibly just to say hello. He finally, however, got around to the real reason for his visit.

“What,” he asked, “is Pat going to do for a career?”

“Well,” said Duke, “maybe because he’s not quite fifteen years old yet I haven’t discussed it much with him. Why, is there a hurry?”

“Could be,” said Ford. “I’m going east next month to make The Long Grey Line and there’s a good part in it for the boy. You said once you didn’t want him to get any bad habits. If he does this it might be the turning point. From then on he might be an actor. You tell me what to do. We can quit now—or go ahead.”

Wayne got up and strolled around the room thoughtfully. “I don’t know, Coach,” he said. “This business has been good to me. It’s a good life. But it’s up to the boy. Why don’t you talk to him. Tell him what you told me—and whatever the two of you decide is all right with me.”

Later that night Ford telephoned. “Maybe you’d better retire right now without a struggle. The boy’s going east with me.”

The months went by and The Long Grey Line was released, and one day John Wayne walked into his office and stumbled over a carton of mail.

Pat appeal

“The mail must be awfully heavy this week,” he said to his secretary. “I haven’t had that much in a long time.”

“It’s not yours,” the girl said. “It’s for your son Pat.”

“Hmmmm,” said Wayne.

Although there is a rare rapport between John Wayne and Pat Wayne a boy seldom ever tells his father everything that is in his mind. Consequently, aside from casual advice, there was never much discussion of movie-making between the two. Pat was interested in school most of the time and when they got together that was what they talked about. Then Duke went to Honolulu to make a picture for Warner Brothers. He got a telephone call from Ford before he left.

“I’m going to the Islands, too,” said Ford, “to make Mister Roberts. There’s a part in it for Pat. Okay?”

“It’s okay with me,” said Duke, “if it’s okay with him.”

And so father and son found themselves that summer both working in the Hawaiian Islands. Pat was on the Island of Oahu, while Duke was working on the fringe of the jungle on Hawaii, 170 miles south.

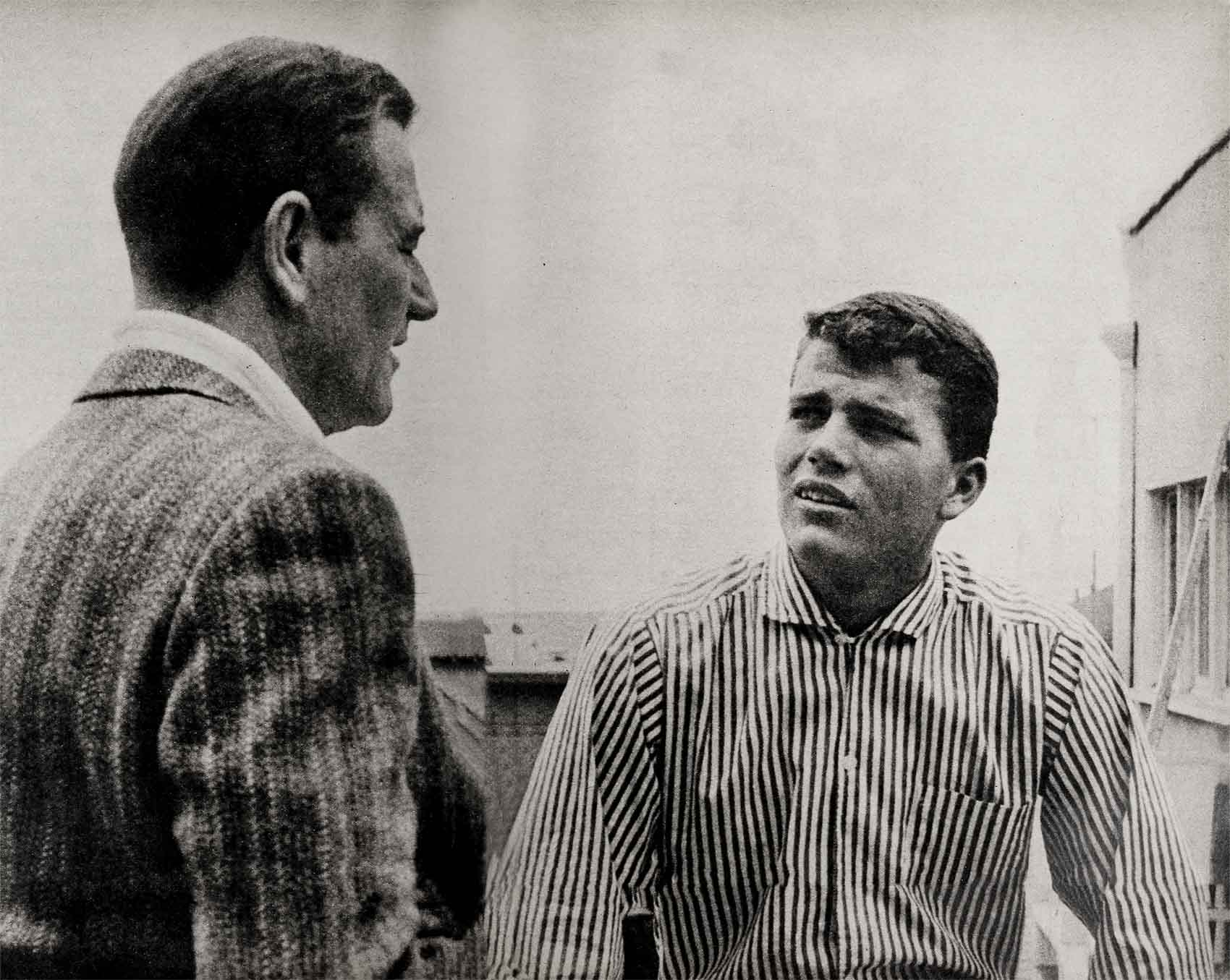

It was a Sunday afternoon. Duke was sprawled in a wicker chair on the lawn of the house he had rented watching the surf spray over the black lava rocks of the nearby shore when a car pulled into the driveway a hundred yards away. A fellow in a T-shirt, navy trousers and a pea cap got out, lugging a duffel bag and started toward the house. He looked familiar.

“Pat!” said Duke. “What are you doing here?”

“I just thought I’d come by for a visit,” the boy said as they hugged. “I got a couple of days off.”

“Well, kick off your shoes and sit down,” said Duke. “I don’t work tomorrow either.”

And they sat by the sea and talked and laughed until it was time for dinner.

The future

Later on, with the moon shining as bright as an arc light through the waving palms, they lay on the grass and felt their full stomachs and listened silently to the pound of the waves as they hit the beaches with a rush that had started in China. After a while Pat leaned up on his elbows.

“I want to talk to you about something, Dad,” he said.

“Go ahead,” said Duke. “I figured you did.”

“Well,” said Pat, “It’s about this movie-acting.”

Duke just waited.

“You want me to be an actor, don’t you?” said Pat.

“I won’t lie to you son,” said Duke. “I think maybe I would. I’ve done all right—and I want you to do all right after I’m gone. But most of all I want you to be happy.”

“That’s just it,” said Pat. “I’m not sure I would be happy being an actor.”

“Have you got something else in mind?” Duke said.

Pat waited a long time before answering. “I’m not sure,” he said, “but I think I have.”

“Shoot,” said Duke.

“Well,” said Pat, “I’ve thought about it a lot—and I think maybe I’d like to be a priest.”

It was Duke’s turn to pause and he did, a long pause. Pat finally broke the silence.

“You wouldn’t like that, would you, Dad?” he said.

“Again I won’t lie to you, son,” said Duke. “I’m not a Catholic, and I didn’t have any idea you thought that way. But I never met an unhappy priest, or a priest that wasn’t a fine man, so I can’t knock it. I suppose that’s something a man has to work out all by himself.”

“I wanted to tell you before I told anyone else,” said Pat. “You wouldn’t try to stop me, would you?”

“No, son, I wouldn’t do that,” said Duke. “But I would want you to be very sure. It’s a one-way road, you know.”

“Thanks, Dad,” said Pat. “I’ve still got to go to college and I’ll have four years to think it out. I just wanted you to know how I felt now.”

“Do you want to quit acting now?” Duke said.

Pat sat up. “Heck, no!” he said. “At these prices?”

They both chuckled at that—and haven’t brought the subject up since. But in the heart and mind of the boy there is the breath of a call. And in the heart of the man there is a prayer that the boy makes the right decision.

The mail since that day in Hawaii has been piling up for Pat Wayne until it’s almost on a par with his dad’s. And there is seldom a week goes by that some producer or another doesn’t call John Wayne asking if Pat’s services are available for a picture. Only C. V. Whitney and Meriam Cooper got anywhere, though. John Wayne himself acted as his son’s agent.

“We have great plans for the boy,” said Cooper. “When you sign this contract Pat will be a star.”

“Oh, no he won’t,” said Duke. “I want a clause stating that he doesn’t get solo star billing.”

“Why?” said Cooper. “Every kid wants to be a movie star.”

“I have my reasons,” said Duke. “And another thing. This contract will only run for four years—until he finishes college.”

“Why?” said Cooper.

“That’s the way it has to be.” said Duke. “And the pictures will have to be made during the summer, so it won’t interfere with his studies.”

“We can tutor him,” said Cooper, “on any subject he picks.”

“I doubt that,” said Wayne. “And at the end of the four years, Pat is a free agent. He can work for anyone else he chooses.”

Cooper’s mouth hung open just a little. “Say,” he said, “has he got another deal lined up for then?”

Wayne walked over and looked out at the blue sky. “It could be,” he said. “Anyway, he’s going to be free to do what he has to do when the time comes. I want him to be happy.”

And that is the way it is today. Pat Wayne’s star is high now. There is no question about it. Within the next four years he will be famous. He’ll make money and be the envy of every boy at Loyola Jesuit College. And then, when he graduates, he can go ahead and follow in the footsteps of his dad—or he can turn the other way and follow in the footsteps of his father. The choice will be his alone.

THE END

—BY JIM HENAGHAN

John Wayne will soon be seen in MGM’s The Wings of Eagles.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956