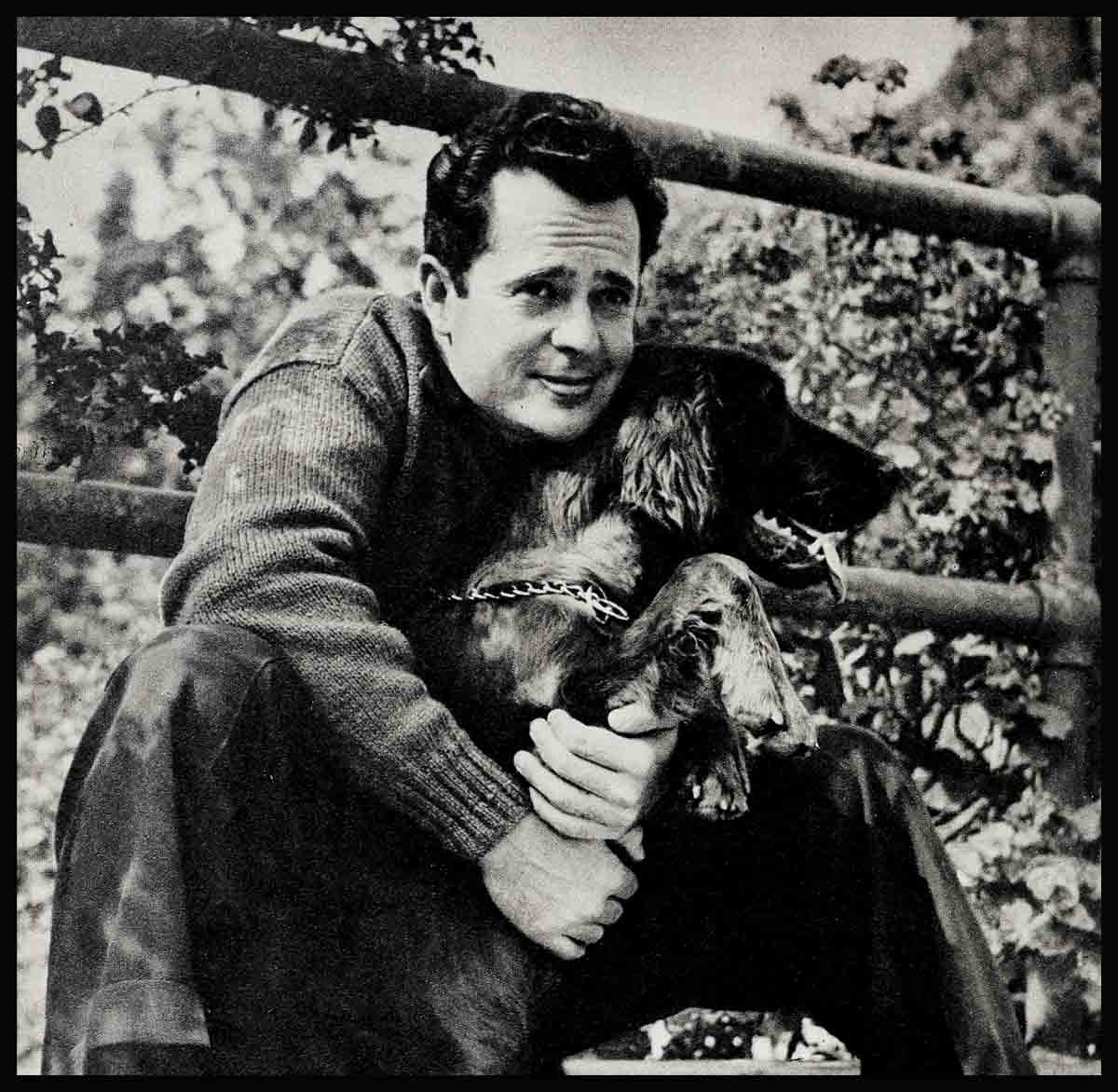

The Winner!—Larry Parks

His name was Malicious, and he was only a horse—but what a horse! He’d amble leisurely out the starting gate at Santa Anita, this nag, with the shout, “They’re Off!” and rock along most of the race in the ruck, eating dust—until they rounded the turn into the homestretch.

Then came the grandstand roar horse-happy Hollywood still remembers with an affectionate thrill: “Here comes Malicious!”

And on he came, that dependable, dead-game pony, pounding past a flashy field to breeze under the wire at the finish—the winner!

Excuse our comparing Larry Parks, MODERN SCREEN’S Man of the Year, with a hustling Hollywood horse of times gone by. By now, Malicious is out nibbling clover in his ripe old age. And Larry Parks—well—Larry has just come from behind to win MODERN SCREEN’S famous 1947 star sweepstakes. He’s our all-out, all-time Popularity Poll Winner, with a record rush of ballots that’s never been matched in MODERN SCREEN’S long life!

Last January, Frank Sinatra had just nosed out Van Johnson in a photo finish for MODERN SCREEN’S ’46 floral horseshoe—and they both started the ’47 handicap breathing easy and far out in front. Larry Parks? A pleasant-looking guy with prospects in the up-coming screen story of Al Jolson’s life—but the other fellows weren’t worrying about him.

And then, over 200,000 of you canny balloteers picked him out of a field of glamor guys. Because Larry stepped forward with the most amazing acting job a brand new star has turned in since Edison invented the flicker machine! The Jolson Story didn’t win Larry his Academy Award—it missed by inches—but it won him MODERN SCREEN’S coveted Poll palm of the year.

So meet the champ—Larry Parks!

Away back in September, ’46, our Hollywood seer, Hedda Hopper, warned “Watch Larry Parks!” in our own pages. Hedda said Parks was terrific. Came summer, and a blizzard of white rave notes turned June into January, right in our own editorial offices. Like Malicious, Larry started slow, and wound up flying. It’s what he’s been doing all his life.

One fall day in 1937, Larry Parks turned the back of his thin summer suit against a biting wind that slashed across 42nd Street and Broadway in New York. He shouldn’t have been there by reasonable rights. He should have been right back at the University of Illinois, starting medical school; he had a scholarship that guaranteed the education. Inside his coat pocket were letters from his parents. “We’ll be heartsick if you throw your future away,” they wrote.

Larry shivered, and felt wet on his neck. Snow. Already the sky was gray.

All summer long, wherever Larry had stepped, a dozen other young, eager, energetic guys and gals had swept along with him, hounding producers, tracking down every threadbare clue to an acting chance, boxing him in. How many got their breaks, he never knew. All he knew was he hadn’t. He turned up his coat collar and started off on the rounds again.

It wasn’t until noon that it dawned on Larry Parks that something was queer. The familiar faces he’d seen all summer—they weren’t around today.

fair-weather barrymores . . .

He stopped short on the sidewalk, snapped his fingers and grinned. “Gone with the snow,” he told himself, “just like the birds. Gone home and given up—oh boy!” He was wobbly from living off noodles and bean sprouts at the Chinese restaurant up the street where you got dinner for 25 cents. He was frowsy and pale from the airless $2.50-a-week room on Tenth Avenue. The seat of his pants was mirror-slick. But what had scared out his sunshine rivals, Larry knew, was his opening. Now was the time to hit ’em again.

He headed straight for the Group Theater. He’d been there the day before, and the day before that. It was what he wanted most—like everybody else—to squeeze inside the exclusive group. All summer he’d been turned down by them, but this time he wasn’t lost in a crowd. Later that afternoon he got the wire, “Please come see us.” It was John Garfield and the Group Theater that started Larry Parks to Hollywood later on.

Larry has been a tough character to discourage on any project since he was nipping along in knee-pants.

Last year, after his mother passed on, Larry had the Parks family possessions shipped out from his home town, Joliet, Illinois. He went down to the storage place to look through them one day, and came home lugging a package. He sat down on the floor and spent the whole evening unpacking and setting up the first major prize he ever won—his electric train.

Larry spotted that train, bright and shiny, racing around a track in a department store window when he was nine years old. It was $34.50—with cars, track, switches, transformer and signals—and that’s how Larry wanted it. But it might as well have been $34,000. That was three weeks before Christmas, and Larry knew his dad couldn’t afford a present like that. He told about the train at dinner that night; he couldn’t help hinting.

Dad Parks looked at his wife and then looked away. “Larry,” he said, “tell you what. If you’ll earn half the price, Santa Claus might dig up the rest.”

Larry had $2.35 in his nickel bank, he remembers, and that left exactly $14.65 he had to rustle—in three short weeks. It was an appalling sum; in his entire young life he’d never earned that much. Sometimes he got ten cents on Saturdays for helping around the yard, and sometimes he didn’t. It was winter and there weren’t any neighbors’ lawns to mow. The corner grocery store had a delivery boy. He tried the newspaper; the routes were all taken. After school, Larry chased around desperately on the trail of jobs. He collected a quarter here, carrying out ashes; he scraped snow off some sidewalks and earned some more. But the last week came, and he had exactly $5.15.

Any kid but Larry Parks might have settled for a pair of skates or a catcher’s mitt. Larry Parks tackled the very treasure house where his dream train buzzed around the window. He went inside and told the department store manager about the project. The boss gave Larry a job dropping packages at doors and what’s more, he said he’d sell him the train wholesale. Christmas Eve, Larry panted in with the money, and his dad’s to match. Christmas morning, his train was racing around his own tree at home.

Larry was 13 when he entered Joliet High and for a peewee, he had gigantic ambitions. He weighed exactly 90 pounds, but he wanted to make the football team and win a scholarship to the University of Illinois. He wanted to be a doctor.

But when Larry had just barely started high school, he was hit by a blighting disease. Bell’s palsy. It twisted the left side of his face out of shape. It’s a fairly rare affliction and tragic. The nerves of your face pull up and twist.

That was bad enough, but almost at the same time paralysis struck his right leg and it withered away to half the size of his left.

Larry took all kinds of violent treatments, including dangerous strychnine. He had to start a campaign of rest and then arduous exercise—harnesses, weights, baths and heat therapy, to bring his paralyzed leg back to life again. He still works out with a weight harness three times a week, and you can still see where his right leg is smaller than his left—but he can use it as well as the next fellow now. The left side of his face, too, isn’t his “good side”—even for a camera. For a long time an eyelid would droop, whenever he got too tired.

two strikes . . .

It would be hard to imagine a tougher handicap for a 14-year-old. He missed months of school, he couldn’t try out for the sports he was dying to prove his tiny body in. By the time he was graduated from Joliet High, he had conquered his twitching face, was walking normally on his stricken leg. Not only that, but he’d actually made end on the lightweight football squad! He was active in student affairs, and even though his grades had suffered during his bedridden days, he went after that scholarship with everything he had. All the budding brains around his Illinois district were after the same thing, but 17-year-old Larry won.

Larry hit the campus at Illinois U. just a freshman lost among fifteen or twenty thousand milling students. Being Larry Parks, he had to do something about that. Besides, he had to earn cakes, coffee and coke money, because his scholarship provided for the future in medical school, but there was pre-med and his BS. to tackle first. He made a good fraternity, S.A.E., took a job slinging hash at the Kappa Sig house. On the side, he earned his board juggling house finances for the Sig Alph brothers. As if that weren’t enough—with his tough study schedule—Parks went all out for the campus theater workshop.

Around Urbana, where Illinois U. sits, they still call Larry’s four-year era, ’33 to ’37, “The Golden Age of Talent.” It happened that Larry bumped up against a rare flock of kids spilling dramatic genius all over the campus. Dozens of that crew have made good all over the land and in Hollywood, too. The competition was terrific, but before he helped himself to a sheepskin, Larry Parks had the theater situation at I.U. all sewed up. He was running the show.

What he went after, he usually got. In fact, the only time Larry got rocked back on his heels during those college days was when he tangled with sweet romance—and a red-headed woman.

Her name was Mildred and she was a gal who got around everywhere, and left sweet smiles and a come-on as souvenirs. Larry started reading blank pages in his study texts, forgot to show up at Workshop rehearsals, spilled soup down an indignant Kappa Sig’s neck one night at dinner and almost got his block knocked off. He had it bad.

There was a certain campus Big Time Operator who had the same idea about Mildred. This BTO, moreover, held a handful of collegiate aces. He played on the varsity, for one, and was always tearing off for long Frank Merriwell runs at the big games, to Larry’s disgust.

He had a profile like Peck, and a red convertible. Larry’s love-sickness made him ignore that superman competition, and Mildred was not one to discourage anybody. She let Larry moon around and think he was head man, right up to her sorority formal.

Larry was snoozing happily in his bunk one night before the big dance. He was dreaming of waltzing Mildred to the formal. His roommate came in late, shook his bunk and woke him up.

“Hey,” he said, grinning wickedly. “I’ve got news for you, Romeo. Guess who’s just broken out with a pin!” Larry didn’t have to guess. He rolled over and rammed his head in the pillow. “She had fat legs, anyway,” he sighed. But he didn’t trust a woman for years after.

The most rugged heat Larry Parks ever ran—and the one he looks back on with the most pride even today—took place one summer in his home town of Joliet, at the Goose Lake brickyard. Larry worked every college vacation because he had to scrape up a stake to start school with in the fall. One summer his dad knew the boss of that fire-brick factory well enough to land Larry a job.

no gold brick-laying . . .

He was 19 at the time, and not too husky for his years. The men he worked with were full-grown laborers with broad backs and seasoned muscles. They worked in teams of four, moving brick from the kiln to the sheds and boxcars. The three regulars weren’t one bit amused at having a college punk shoved into their circle by the boss’s friend. The Goose Lake Yard paid off by piece work—so much for shifting each 1,000 bricks—and the four-man team drew their pay as a unit. The job wasn’t a vacation interlude for the brick-heavers; it was their bread and butter. If this kid slowed them down, they’d have less to eat at home.

Larry still aches, remembering that summer. His crew hardly spoke to him, they scorched him with dark looks, and they set out to work him to death so he’d yell “uncle” and quit.

They had the know-how and the strength to hoist 600 pounds of firebrick aboard the rubber-wheeled barrows and scoot them along. To Larry, until he learned, it was like hoisting the city hall. They were used to the white-hot kilns where the bricks glowed incandescent with heat and where, if the fan went out, you’d fry like a piece of bacon in a few sizzling seconds. But Larry clamped his jaws and sweated, choked and grunted until his muscles almost snapped. At night he went to bed almost crying from fatigue and he dreaded each dawn.

But he wouldn’t quit, and after a month he was brick-tough himself, broken in and handy. So handy in fact that he ended up pals with his team and their four-man gang made more money than any crew in the yard. He got a job there the next summer, too, welcomed that time as a heaver who’d proved himself.

There’s never been a sign of the white feather in Larry’s makeup. If he hadn’t been built to stick things: out, we wouldn’t be hailing him now as MODERN SCREEN’S Man of the Year. Because he had to pitch plenty to stay in the Hollywood ball game, even after he’d won himself a lucky pass into the park.

That was after Larry’s Broadway invasion, a fling at summer stock, and graduation from Illinois. You see, he got sidetracked from that medical career by all those college dramatics and the minute he slipped out of his cap and gown at Commencement, he sat down and wrote fifty letters to summer stock companies he’d read about in Theatre Arts Monthly. The law of averages fixed him up. He got twenty answers and seven offers. He picked the Manhattan Players at Lake Whalom, Mass., on the straw-hat circuit, then buffeted Broadway in the fall. That’s when he outlasted the fair weather boys and girls and got that last minute job with the Group Theater. John Garfield, who’d traveled on to Hollywood after stage fame in the Group’s Golden Boy, soon had a job for Larry in movieland.

It was to play Johnny’s brother in a picture called Mama Ravioli at Warners. Larry hustled out to Hollywood on a bus, ready and set to go. Old eight-ball Parks, they call him. He was in Hollywood with an acting job one Saturday night. By Monday morning the picture was cancelled, the job gone, and he was broke.

Once he’d skinned knuckles enough rapping on studio gates, he started beating his brains out about the business of eating.

minstrel-man parks . . .

He’s told before about the house he and two old Illinois U. pals hammered together. They parlayed a $400 loan into a $4,000 house, sold it and cleaned up enough to coast along on for months. But I’m not sure he’s ever revealed the Hollywood variety career of Larry Parks and Co., songs, dances and snappy patter.

“We swiped blackouts, skits and sketches from anywhere,” Larry confessed. “No show was safe. And sometimes we made up a killer-diller of our own.”

Larry and his boys (a lot of other hungry hopefuls) were ready day and night to fling a show—anywhere. They operated all over Southern California—Kiwanis banquets, sales conventions, and firemen’s balls. Once they whipped together a complete musical show in three days, and they got $200 for that. Another time they ad libbed a show off the back end of a truck and collected $5 for the whole act, split four ways. It wasn’t elegant or a road to riches but it kept Larry alive.

Most everyone knows by now that Larry Parks first slipped into Columbia with a pinch hit reading of Robert Montgomery’s part in Here Comes Mr. Jordan. They weren’t testing Larry really, but Barry Fitzgerald for a key part. Columbia’s head caster, Max Arnow, needed someone to make the test with Barry. He called Larry and asked if he’d like to fill in the test— no promises made.

Larry stepped inside the lot that morning when the gates opened. Minute he saw the set where the test was scheduled, he raced back home and snatched his roommate’s dark blue suit. He’d spotted the white marble set, and his brain clicked. Barry Fitzgerald showed up in a light suit and faded into the white background when the film was printed. Larry stuck out like a sore thumb and loomed twice as tall and impressive as he really was. Barry Fitzgerald didn’t get the job in Here Comes Mr. Jordan, but Larry Parks got a contract at Columbia. He had to laugh, later, when the studio big shots looked him over in the flesh. “We thought you were bigger,” they muttered.

Whether that let-down did it or not, Larry Parks found a stock contract was no pass to fame. He had to chug along unhonored and unsung for several years.

He made thirty pictures. He played waiters, chauffeurs, mashers, bums. He filled in in mob scenes, he did dangerous stunts because he was cheaper than a Hollywood stunt man. He wallowed in Western shoot-em-ups, Blondie serials, gangland chillers. When he did see a little light, as in Counter-attack, it got snuffed out, pronto.

Larry struggled through that picture for weeks, with high hopes. He was Paul Muni’s friend in a war story, and he had a hero’s part. Most of his role was played in a swamp—a studio water tank—and if you’ve ever seen one of those torture tubs, you’ll know it was no picnic. It was cold and dirty and Larry stayed there, sopping wet, day in and out, giving everything he had.

He hustled eagerly down Hollywood Boulevard the night of the preview. On the marquee of the Pantages the banners read: Counter-attack with Paul Muni, Marguerite Chapman and Larry Parks. He could hardly believe it. “This is it,” he said to himself, glowing.

But you’d have needed a torch to find him in that picture. His part, he soon realized with a sinking heart, had been scrapped. What few feet remained saw him wandering around in dim light between the swamp and a bombed out cellar and you couldn’t tell whether that hazy character was Larry Parks or the Shadow.

He stalked home to his room and wrote a girl named Betty Garrett, back East. He told her the punctured payoff, as he’d told her his hopes. “Never mind,” he scribbled, “I can out-wait ’em.”

Betty knew Larry would crash through someday. She knew him pretty well by then; she was his bride.

They’d met in New York and again in Hollywood, at the Actor’s Lab, and Larry knew what he wanted.

Two careers kept Betty and Larry Parks apart all during the toughest stretch of Larry’s career, the eight month marathon to his long-delayed fame in The Jolson Story. Betty was starring in Call Me Mister on Broadway, and a 3,000-mile-away wife was just one more misery Larry had to bear in that most important year in his life. Most of the others you’ve read about:

How Larry—who wasn’t a real singer—had to mimic perfectly one of the greatest of them all, Al Jolson. How he started the picture stone cold, with no chance to prepare, being cast at the last minute. How he put across twenty dynamic Jolson numbers, all different, and matched every Jolson quiver and mugg to the flicker of an eyelash. He slaved 14 hours at a stretch, day and night, through those eight months until he almost lost his mind, till the old facial palsy threatened to come on again. It wasn’t made easier by the knowledge that his mother, who lived with him, had cancer, was getting steadily worse and would die, perhaps before she could see the success he was striving for. But maybe that helped him last out the race.

Because when he thought he couldn’t stand the strain another minute: when he was ready to explode, he thought of his mother.

At home she was pretending not to know what was wrong with her. “If my mother can be as calm and cheerful as she is, I can certainly take my troubles without any kicks,” he figured. So he didn’t let up for a minute, and his mother lived to see her boy come through. The Jolson Story and Larry Parks are big, bright events in Hollywood’s spangled history. It will be a long time before a player and picture miss an Academy Oscar by as little as Larry Parks and The Jolson Story did.

All that is a year gone by for Larry Parks, and he isn’t looking back. But he’s still hustling along the hard way, running an obstacle race. It seems to be his destiny.

He hasn’t been able to clinch the biggest break of his life as most screen star sensations do, because practically every minute since The Jolson Story he’s been feudin’ and a-fightin’ with Columbia and his boss, Harry Cohn. Larry hasn’t stepped on a movie set, at this writing, for nine long months.

What makes him fret about the whole knotty business is that most people think his sudden fame has made him hard to handle. He’d like to clear that up.

Larry’s battle with his studio has nothing to do with money. What he’s wrangling about concerns a contract signed before, not after The Jolson Story. It boils down to this: Larry says he has a year more to go on his contract. Columbia says he has five. He’s up for a suit for “declaratory relief.” That’s lawyer language, but it means a verdict to clear up Larry’s studio future. If he wins, he’ll go right back to work for another year, and then call his own shots. If he loses, he’ll be Mister Columbia for five more terms. Larry’s betting he’s right and, like we’ve been saying, the boy has a habit of winning.

But win or lose, Larry Parks will always find something around Hollywood to go after and get. Battle’s the breath of his life—even if it’s only with himself. While he’s been idle, Larry licked a complex he’d been lugging around ever since The Jolson Story.

gentleman in the dark . . .

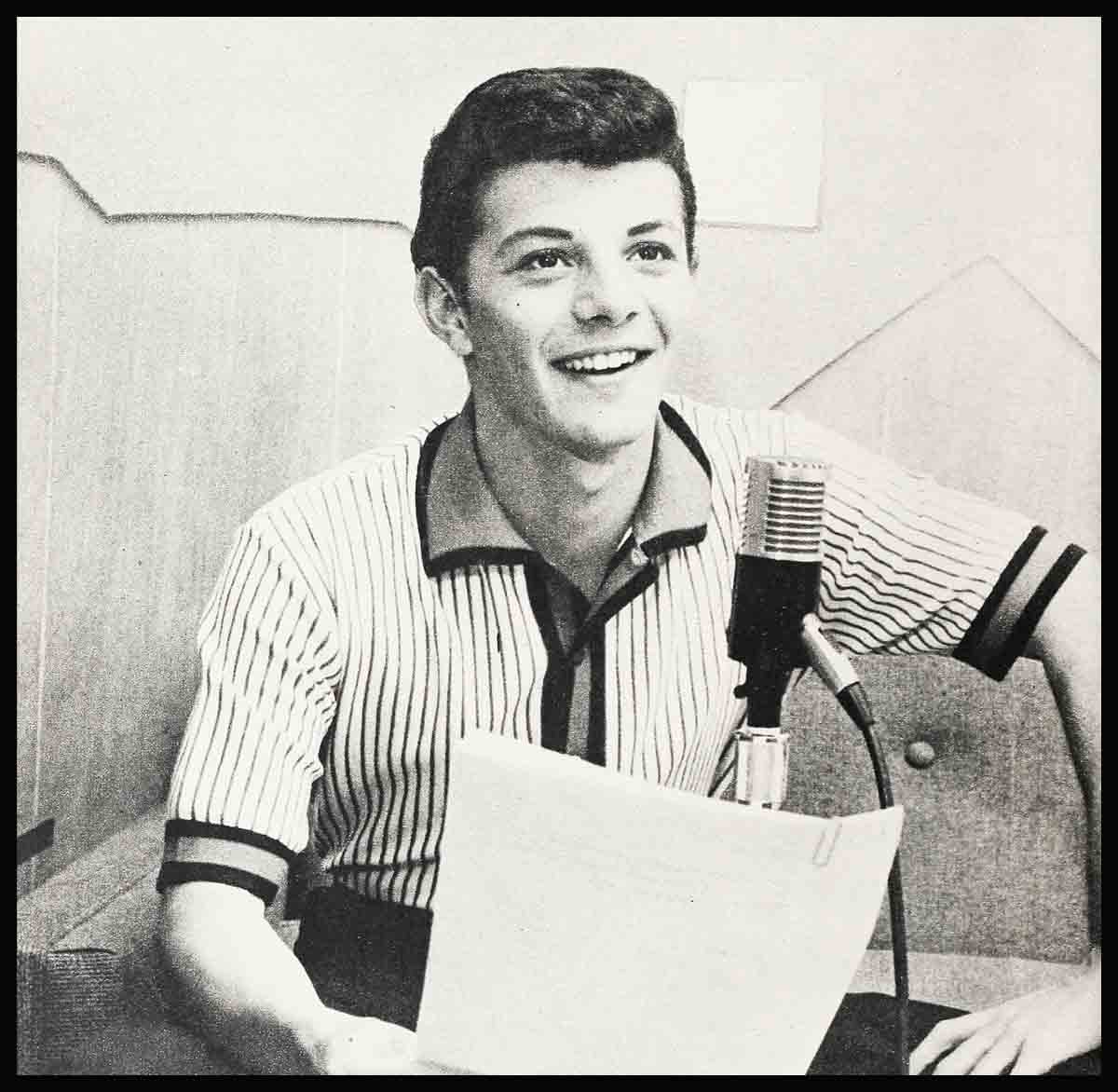

It wasn’t all because he played “the silent Jolson” in his big hit, didn’t sing a recorded note, and everyone knew it, that Larry found himself saddled with a very real psychosis. What built up the fixation was Larry’s natural love for singing, and his flop feeling in public when he couldn’t, because he didn’t know how to do it right.

He’d travel around with Betty to the GI hospitals and Betty would whip right into a number that scattered sunshine all over the place, while Larry, who had a good baritone, couldn’t even think of using it without being terrified.

Betty understood. She brought Sy Miller. her voice coach, over to the house and they ganged up to coax Larry into a song or two. Sy told him the truth—that he had a good voice, could train it and learn to sell a song like the best of them. Larry snapped at the chance.

He’s been taking voice lessons all-out and faithfully, three times a week for the past six months. His last-set of recordings were so good they banished his bugaboo. Right now, Larry and Betty are working out a family singing act which they’ll perform in public the next time they’re asked.

The song they plan to sing is from Annie Get Your Gun. It’s called “I Can Do Anything Better Than You,” and while Larry’s too modest a guy to believe it, the song’s a pretty good theme for him. He can do almost anything better than almost anybody. Could be that’s why he’s MODERN SCREEN’S Man of the Year.

THE END

BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JANUARY 1948

No Comments