The Vintage Years—Spencer Tracy

A good many years ago, a young man who wanted desperately to be an actor got himself a job with a stock company in an Eastern city. It wasn’t much of a job, but then the young man wasn’t much of an actor at the time. He was given little parts—walk-ons, one and two-line bits. Whether he did them well or poorly would be hard to tell now, because nobody then was paying much attention to a fellow named Spencer Tracy.

Except maybe the star of the company, actress Selena Royle. She thought the young man had talent, and the time came when she pleaded with the director to give him a chance in a much larger part, one which ordinarily would have been filled by a more firmly established actor. Because Miss Royle was a star, the director agreed, but not without misgivings. Those misgivings were thoroughly justified. The young actor, nervous and trying too hard, forgot his lines on opening night, missed cues, and bollixed up the play to a truly remarkable extent.

The director promptly fired him, and Spencer Tracy departed for New York that same night, feeling like a whipped puppy and convinced that he would never be an actor. Fortunately, time was to prove he was as wrong as could be.

Twenty years later—give or take a few—Selena Royle, no longer a star, went to Hollywood to play a small part in an M-G-M picture. One day, she mentioned to a co-worker, an M-G-M contract player, that she’d once known Spencer Tracy. “But he wouldn’t remember me after all this time,” she added.

“Let’s go over to his sound stage and see,” urged the acquaintance. Reluctantly, Miss Royle consented.

It happened that they entered the sound stage while Spence was rehearsing a difficult scene. They stood quietly among the thirty or forty assorted technicians, prop men, script girls, and sub-sub assistants who clutter up the sidelines of every active set. Spence, absorbed in his work, didn’t even glance in their direction. Then, after a few moments, he seemed to become aware of something a bit unusual. He looked up, frowning, narrowing his eyes against the light. Suddenly he yelled.

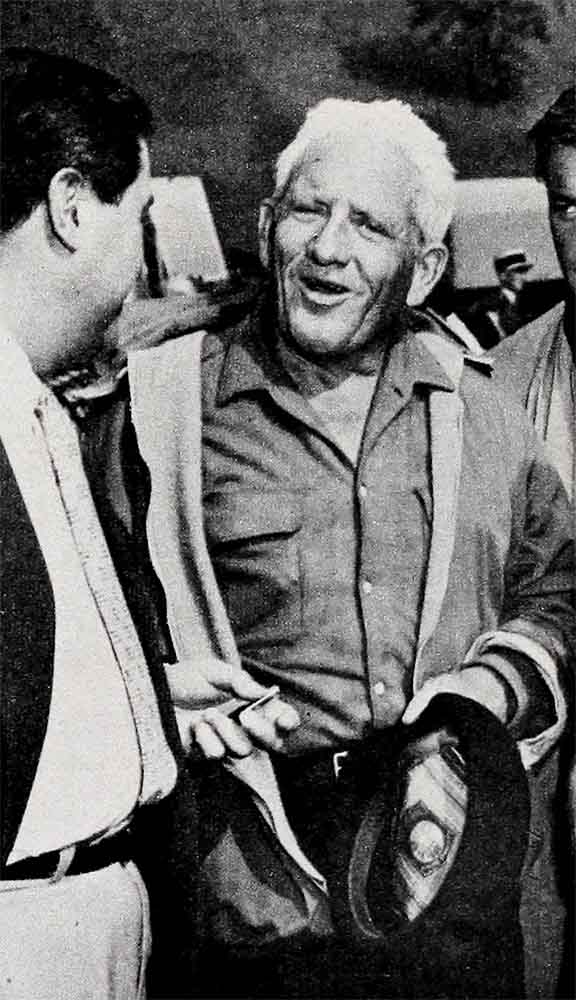

“Selena!” Rushing off the set, he grabbed both Selena’s hands, then threw his arms around her in a bear-hug. “By golly, it’s wonderful to see you! How are you?”

This little incident illustrates Spencer Tracy’s phenomenal memory, but it also illustrates something more—his loyalty to a friend. Not the casual, easy kind of loyalty, which would have permitted him to continue rehearsing until the director called a break, then stroll over and greet Miss Royle with smiling, poised friendliness; but the dynamic, positive kind which made him forget everything except that a person whom he’d been fond of a long time ago was standing there.

Loyalty—and also humility. For it was Spence, not Selena Royle, who a few minutes later proceeded to tell all within hearing how she had gone out on a limb to give him his first big acting chance, and how disastrously he had bungled it.

“I wondered,” he said, “what had ever given me the idea I could act.” He paused and looked thoughtful. “Still wonder that, sometimes,” said the man who has twice won an Academy Award for the excellence of his acting.

Nor was he being falsely modest. There is not one ounce of phoniness in Spencer Tracy. He simply and sincerely does not have, and never has had, a high opinion of his own abilities. Time and again he has pleaded not to be cast in this or that role because he was convinced it was beyond him as an actor. “Who’ll believe I’m a Portuguese fisherman?” he demanded when M-G-M wanted him to play Manuel in “Captains Courageous.” “With this Irish mug? And I can’t learn that accent—I’d mess up the whole picture!” Later, when he was offered the role of Father Flanagan in “Boys Town,” his reaction was even more violent. “Me, a priest?” The Irish mug twisted as if in pain. “Why—it would be sacrilegious!”

However, he did play Manuel and Father Flanagan. Those were two roles for which he received Oscars.

Spence had been under contract to M-G-M for twenty years—longer than any other star on the lot—but this year he decided to become a free lance, as have so many other stars. As far back as 1952, having read The Mountain, by Henry Troyat, and Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, Spence had asked M-G-M to buy the stories for him, but to no avail. So, after he became a free lance, he arranged with Paramount about filming “The Mountain,” and with Leland Hayward about producing “The Old Man and the Sea.” “The Mountain” will be released this fall, and “The Old Man and the Sea,” which is now being filmed in Cuba, will be released early next year.

On his last birthday, April 5, Spence was fifty-six. He doesn’t mind revealing his age, nor does he make any attempt to appear younger than his years. Along with his professional humility, Spence has a complete lack of personal vanity. Long ago he declared, “I’m not the romantic type, and—” he added, sticking out his square jaw and popping eyes, “I can prove it!” No make-up artist has ever been permitted to pretty him up for a picture. Unless his role demands it for purposes of realism, Spence wears no make-up at all before the camera. His hair, once a bright red, is silver now, and the lines striping his forehead and raying out from the corners of his quizzical blue eyes are deeper than they used to be. Only his freckles are unchanged.

Spence was born and brought up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he had thought less of being an actor than most youngsters do today. His father was local sales manager for a motor truck company, and the Tracys were “not rich, not poor, just comfortable.” Spence thought, when he was in his teens, that he’d like to be a doctor, but first there was the little matter of World War I to be settled. He and a friend, Bill O’Brien, managed to enlist in the Navy, although they were both under the minimum age limit, and served five months before the war ended.

That out of the way, Spence entered Ripon College as a pre-medical student. During his freshman year he went out for the debating team—and that was the beginning of the end as far as his medical plans were concerned. “The dramatic coach watched me debating,” he says now, “and spotted the ham in me. He gave me a good part in a play, and from then on I was a goner. I decided I wanted to be an actor; I’ve never changed my mind.”

Since he was going to be an actor, Spence saw no point in studying medicine, and in the middle of his third term at Ripon he left college and went to New York, where he enrolled in the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. In the meantime, his boyhood chum, Bill O’Brien, had also been bitten by the acting bug, and they took a furnished room together. Bill had changed his first name to Pat by then, and in the years since he hasn’t done too badly in the acting line either.

The boys had a lot of fun and a lot of heartbreaks—just as other boys (and girls) equally determined to be actors are having today. “We had one advantage, though,” Spence says soberly, “that youngsters today don’t. Stock companies, outside of New York. Places where we could learn how to act, doing a different part in a different play every week—and still earn enough to live on. Hardly any stock companies left now. A kid either gets a job on Broadway and, if he’s lucky, keeps it and does the same thing six nights and two matinees a week for a year or so—or he gets discouraged and hungry and goes back home. Of course, there’s radio and TV—they help some.’

Spence’s first stock engagement was not, as mentioned, conspicuously successful. On his second try, he did better. He was hired by a company in White Plains, New York, to play juvenile leads. And, as if that weren’t sufficient proof that fortune was on his side, in the company there was a beautiful young actress named Louise Treadwell.

They played love scenes on stage, and very soon they were playing them offstage as well. By the time the White Plains season was over, Spence had proposed and Louise had accepted. They were married on July 28, 1923, and they’ve stayed married ever since, through the lean years and the fat ones.

Perhaps one reason for the success of their marriage is that it has been kept separate from Spence’s career. In a town where a star’s private life is considered public property, Spencer and Louise Tracy have avoided the spotlight and shielded their home and home life from prying eyes. It is no secret that their happiness was early shadowed by the hearing deficiency of their first child, John, who is now thirty-one, but it is something Spence never talks about for publication. Neither is it any secret that he and Louise founded the John Tracy School for the training of other children similarly handicapped. But again this is a fact which is never allowed to serve as an excuse for any publicity connected with Spencer Tracy, the star.

Today, Spence is quietly proud of all his son has accomplished, despite his handicap. John was graduated from college with honors, is carving out his own career as a cartoonist, is happily married and the father of a three-year-old son.

Spence and his wife have the kind of warm, affectionate relationship you find between two people who have shared both happiness and sorrow—who understand each other completely and have found their way to a mature, undemanding love. When Louise Treadwell became Louise Tracy, she gave up her own acting ambitions, willingly and entirely. John was born when she and Spence had been married a year. Their second child, Suzy, was born in 1932, after success on the stage had brought Spence to Hollywood and greater success. Louise’s part in that success was to provide a home, a haven. A charming, dignified woman, she now spends most of her time at the Tracy ranch near Encino, coming into town only rarely.

Spence has a far more difficult, seeking temperament than his wife’s. He loves the ranch, which he likes to believe is a real one. It isn’t. Real ranches don’t lose money; this one does, mainly because its owner’s ideas of ranching are strictly his own. Spence has acres of rich pasture in which he refuses to plant money-making crops because he needs them to support the race horses and polo ponies he has acquired at different times and never sold. He can’t bear to sell them, because if he did they might have to go to work. He also raises turkeys and chickens, all of which die of old age because Spence can’t bear to have them killed or sent to market.

But, since there has always been a streak of restlessness in Spence, he could never be happy as a full-time gentleman farmer. He needs the stimulation of people and activity and new scenes. So, while he is working on a picture, he lives from Monday to Friday in a small, comfortable Hollywood apartment, spending only his weekends at the ranch.

He is bored by gaudy night spots, but he loves good food and knows which restaurants serve the best. He has a great many friends, most of them connected with the film industry. Among the closest are Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, Stewart Granger and Jean Simmons, Leo Durocher and Laraine Day, Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon, directors George Cukor and William Wyler, executive Benny Thau, agent Bert Allenberg, Clifton Webb, Richard Burton, Ernest Hemingway—and the oldest friend of all, Pat O’Brien. It is no accident that all these people: are witty and entertaining conversationalists. Spence can’t abide dullness, in himself or others.

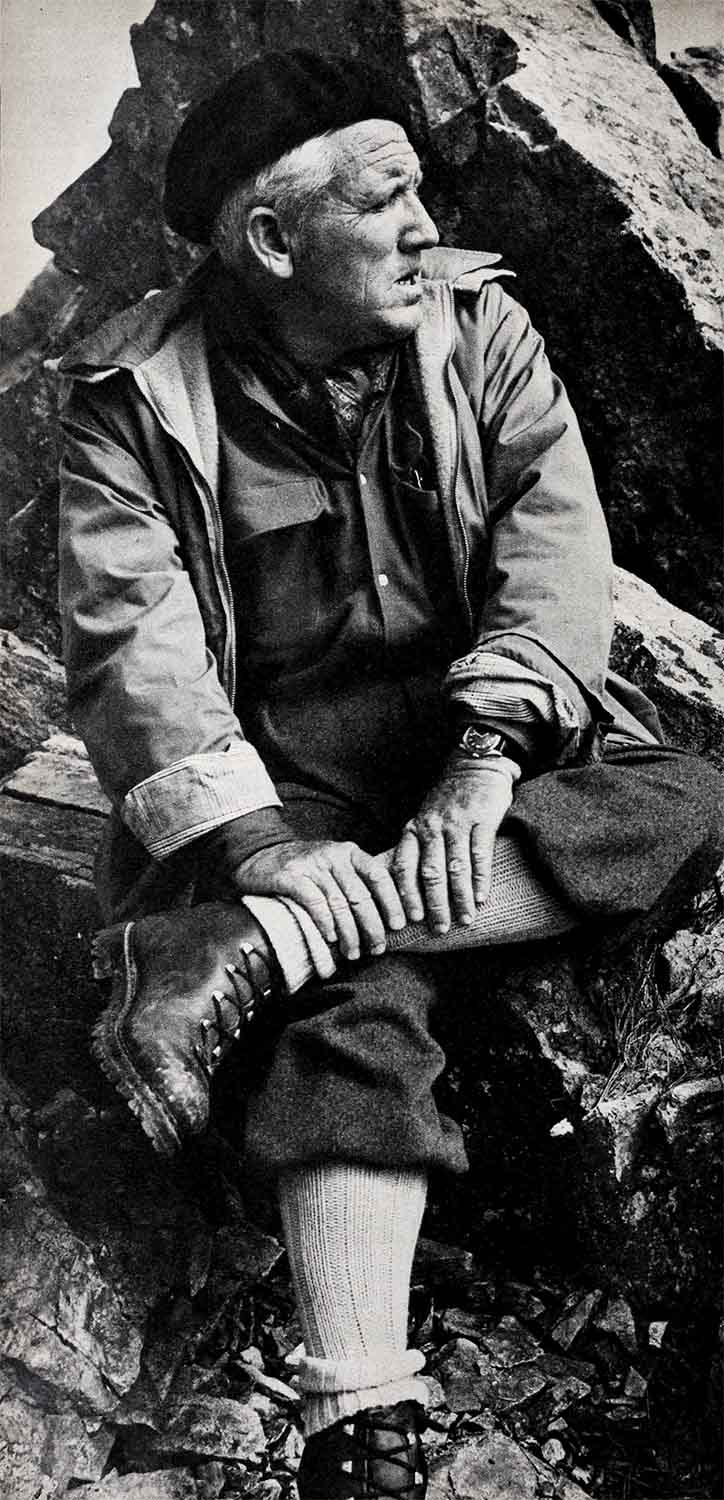

Several years ago, he took up oil painting as a hobby, but he is not one of those amateur painters who shows his efforts at the drop of a hint. Only his family and a few very close friends have ever seen a completed Tracy landscape. He is even reticent about the fact that he paints at all. While on location at Lone Pine, California, making “Bad Day at Black Rock,” Spence disappeared one morning when some scenes in which he didn’t appear were scheduled for shooting. No one knew where he had gone. Finally, he was discovered at Whitney Point, a spot on the mountainside commanding a magnificent view which he was trying to paint.

“Why didn’t you tell me you were going up there?” asked the studio publicity man assigned to the company. “I’d have sent a photographer up to get some shots of you painting.”

“That’s why,” Spence said, with a grin.

It’s not that he isn’t cooperative. Simply, some things are his own property, not to be exploited for the sake of publicity.

Spence can be stubborn about such things—about anything that he feels conflicts with his integrity as a person or as an actor. He has a temper which has earned the awed respect of front-office brass. But it’s notable that less exalted studio workers—grips, wardrobe men, bit players—speak more of his kindness than of his temper.

Younger actors he has worked with, especially, idolize him. People like Jean Simmons, Bob Wagner, Van Johnson, will tell you by the hour of his patience and helpfulness at times when they were unsure of themselves.

If there is time between pictures, Spence likes to take a trip of some kind. For instance, as soon as “The Mountain” was finished, he took off for Paris, along with Robert Wagner and Barbara Darrow. Assuming the role of tourist-guide, Spence showed them what he calls “My Paris”—the little cafes, the art galleries, the colorful side streets.

Spence and Bob Wagner had worked together before, in “Broken Lance,” and while shooting “The Mountain” they became even closer friends. Bob has long idolized Spence, and apparently the “master” has a high regard for his young “protege,” for it was Spence who picked Bob to play opposite him and insisted that he get co-star billing.

“The Mountain” is an exciting, breathtaking picture. It tells the story of many conflicts—between right and wrong, kindness and greed, younger and older brother, and most of all, between man and mountain.

Most of the picture deals with the ascent and descent of the famous and hazardous Mont Blanc. In order to prepare for the rigors ahead, Spence and Bob arrived in the village of Chamonix, France—which lies within the shadow of Mont Blanc—three weeks ahead of schedule. For days they worked with Alpine guides, practiced climbing over snow and ice, jumping over crevasses, climbing steep, craggy cliffs.

Charles Balmat, one of the most famous Alpine guides, was in charge of training the men. “You can always tell an American in the Alps,” says Balmat. “They always want to get to the top in fifteen minutes. You can’t do that in the Alps.”

Throughout all the arduous training and filming, Spence kept up with the pace set by the guides. He was in constant danger, and at no time during the climb did he— or anyone else—feel safe. The first day of climbing, the weather was calm and beautiful. As they proceeded on their way, everyone felt good and confidently exclaimed, “This is a cinch!” Then, just a short way up the mountain, they suddenly found themselves in the midst of what Charles Balmat called “the worst storm Chamonix has ever had.” As lightning and thunder crashed all around them, Balmat shouted, “Drop everything and run for your lives!” But where can you run when you’re scaling a mountain? And even if they had known where to run, the storm was so bad, they couldn’t see two feet ahead. They did manage to crawl back, finally, but in the process one of the porters was struck by lightning.

The people of Chamonix were delighted to have “The Mountain” company visit their town, and in honor of the occasion they gave numerous parties. Although Spence led a comparatively quiet life while on location, he did attend some of the parties and, understandably, captured the hearts of the townspeople. Before long he became known as the Pied Piper of Chamonix, because he frequently strolled down the main street, handing out candy to the children who gathered around him.

One of the unpleasant aspects of making “The Mountain” was having to start work before dawn—unpleasant to everyone, that is, but Spence. He has never needed much sleep—about four hours a night does him nicely—and is always awake by six A.M., at the latest, whether or not he is working on a picture. Similarly, in the evening he is still likely to be bright-eyed and eager when everyone else in the party is beginning to droop. This may be partly due to the fact that he drinks nothing stronger than coffee—gallons of it. There was a time when this was not so—when, in fact, Spencer Tracy seemed bent on earning himself the reputation as a hard man with a bottle. Seven years ago, without fanfare, he went on the wagon and has remained there ever since.

No matter what time he goes to bed, Spence reads for an hour or so before falling asleep. Then, as soon as he wakes up, he brews a big pot of coffee, which he drinks while he reads some more. He reads fiction, history, biography, and every book about the theatre he can lay his hands on.

He doesn’t own a television set. He and Ernest Hemingway made a pact several years ago that as long as there are still words being printed on paper, neither of them will buy a television set.

“I wouldn’t want one anyway,” Spence says. “I’ve got no self-control around television. I take a trip to New York, I bring along a stack of books I want to read, I plan on seeing a few plays and a few friends. There’s a television set in my hotel room, and I snap it on. So what happens? At two in the morning I wake up and find I’m still sitting there.”

Speaking of Hemingway, he and Spence have recently had the opportunity to extend their friendship into a working relationship, during the filming of “The Old Man and the Sea,” on location in Cuba. As in “The Mountain” the chief conflict is between man and mountain, so this story is about man’s struggle with the sea and its inhabitants. It tells of a poor, elderly Cuban fisherman who catches an unbelievably large marlin but, by the time he brings it into port—after all kinds of struggles—there is little left but the skeleton. The role of the old fisherman is a tremendously difficult and taxing one, and Spence carries the story almost single-handedly.

Not the least of the problems involved in filming “The Old Man and the Sea,” was catching a huge enough fish. Along with several others, Ernest Hemingway tried his experienced hand at it. And, while he was attempting to make the biggest catch of his fishing life, Spence was busy preparing for the role that could snare him the unprecedented honor of an actor’s life—the Oscar for the third time.

It is a strong possibility and, if it does become a fact, it will be the richest harvest Spencer Tracy could reap in these, his rewarding vintage years.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1956