The Small, Private World Of Audrey Hepburn

At a long table set up on the second floor of the Eiffel Tower, in Paris, the cast and crew of Paramount’s “Funny Face,” headed by Audrey Hepburn and Fred Astaire, were having lunch.

When Mrs. Stanley Donen, wife of the director, walked into the room, carrying her baby son in her arms, Donen rose quickly. “We must get another chair,’ he said, looking around for one as he relieved his wife of the child. But it was Audrey Hepburn who quietly and inconspicuously left her place at the other end of the table, found a chair, and carried it over to the director’s wife.

Another day, a little French girl, a member of a ten-moppet choir group used in one scene of “Funny Face,” burst into tears as the high-powered klieg lights blinded her unaccustomed eyes. It is doubtful whether she realized that the gentle, kind young lady who dried her tears and comforted her was a famous International actress and the star of the picture.

A movie company on location lives and breathes as a big family unit, but not always a congenial one. Every working day produces crises and situations to test the hardiest spirit. Under these circumstances, it’s almost an impossibility to cloak one’s real nature. Not many stars can survive such a test; a few come through with only passing marks.

AUDIO BOOK

At the wind-up of “Funny Face” in Paris, not only was the company cheering for Audrey Hepburn in one fervent voice, but most of its male members were a little in love with her. The French crew dug into their faded blue jeans and got a collection to buy her a magnificent bouquet of roses, then proudly went home with autographed pictures of her for each member of their families. “La petite, elle est formidable” (“The little one, she is terrific), one Gallic crewman summed up his fellow workers’ sentiments about Audrey.

Simple graciousness and good breeding have always been a part of Audrey Hepburn’s nature. But it has been since her marriage to Mel Ferrer, especially, that she has achieved a quiet directness and warmth in her relations with others, with her work and with herself, which is the direct result of the happiness of a woman in love.

Audrey gives of herself and her friendship with caution. A hypersensitive nature, aggravated by her harrowing war experiences, has caused her to shrink shyly from a too casual friendliness. But since her marriage she has learned how to unbend. Although still not a social butterfly, preferring quiet evenings at home with Mel, she can now throw herself into a convivial gathering with zest.

The crew members of “Funny Face” recall, among their most memorable Parisian experiences, the two dinner-dance parties Audrey and Mel gave for them. Audrey, as tireless at festive occasions as she is at work, danced with all the men. When she learned at the first gathering that it was the unit production manager’s birthday, she asked the restaurant chef to improvise a birthday cake, and she led the guests, who included Ingrid Bergman, in singing “Happy Birthday.”

Her marriage, despite its relaxing effects, has also intensified her taste for seclusion. She needs no outside influences to enhance her happiness when she is alone with Mel. “I’ve been spending more time being a wife than a star, and I’m very happy about it,” she said.

To Audrey, marriage is heaven on earth, and she can’t understand the state of bachelorhood at all. “I never really appreciated the joys of being able to share one’s precious moments with another person until I was married,” she remarked.

Mel, with that exquisite good taste of which he and Audrey both have an abundance, very seldom came to the “Funny Face” set to see her. But it was never very difficult to know when Audrey was expecting him. Always in a bubbling good humor, she was truly radiant on those days.

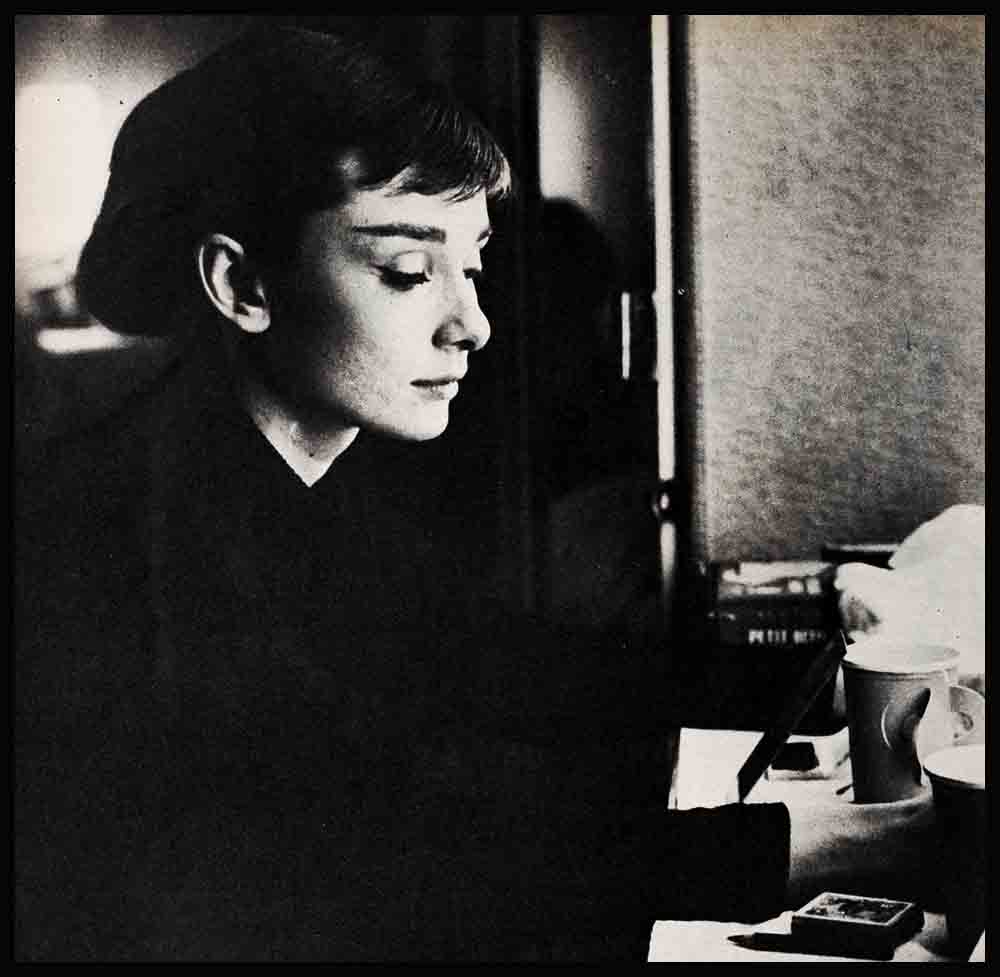

On one particular day, even the sun decided to cooperate. The Sacre Coeur glistened white and gleaming on the Butte of Montmartre, as the company broke for lunch. Audrey had changed into light cotton slacks and a black high-necked sweater, and her long hair was ribboned into a pony-tail. She sat at a table near the window in the cafe which was serving as the troupe’s headquarters. Humming softly under her breath, she kept her eyes glued on the cafe door.

Suddenly, one of those rickety old taxis which are as much a part of the Paris scene as Notre Dame rumbled to a stop in front of the cafe, and Mel disentangled his long legs from within it. Audrey, her face lit up like a Christmas tree, dashed outside.

Mel grinned broadly, greeted her with, “Hi, gal,” and drew her toward him, kissing her gently. “Well, how did it go today?” he asked, as he put his arm around her. “Did you get much done?”

Audrey recounted the morning’s events with animation, her words tumbling out in her eagerness and pleasure at seeing him. An unknowing onlooker would have thought they had been separated for weeks rather than a few hours. “And you, what have you been doing, darling?” she finished, and looked up at him tenderly.

Mel took her hand and they strolled slowly into the cafe, while he told her of the set of tennis he had played and of the morning’s mail. He greeted the rest of the company with a smile and handshakes, and then led Audrey to seats at the film unit’s long table.

Audrey surveyed the table, which had already been set for the first course, with a critical eye. Then, beckoning to the waiter, she whispered in his ear.

“What’s this?” Mel commented, as the waiter brought another portion of ham.

“You know you don’t eat enough,” Audrey chided him.

“You’re the one who should eat more, not I,” Mel answered. “Just think of all the energy you use up with your dancing. Now, come on, eat up,” he said in mock authoritative tones.

All during the meal, they grinned at each other and chatted animatedly, or exchanged comments with Stanley Donen and Fred Astaire, who were seated nearby. From time to time, they glanced at each other’s plates to see if the food was being properly consumed. When the waiter had cleared the table, Mel took Audrey’s hand and held it in his. He didn’t let go of it until they had finished their mint tea.

“I have only a half-hour before I must change,” Audrey sighed.

“Just time for a stroll,” he said.

They walked off, hand in hand, radiating a cloudless happiness that was the envy of all who looked at them.

Back on the set, Mel watched the rehearsal of one scene, and then made a sign to Audrey that he was going. Her face clouded a little, but she respects his wish never to interfere when a scene is being shot.

He bent down and kissed her on the top of her head and took her hand. They walked to the taxi stand.

“Remember, it’s Saturday and no work tomorrow, so we’re going out to dinner tonight,” he reminded her. “What are you going to wear?”

“Oh, gosh, yes,” Audrey sighed. “The same old problem. What about the beige dress?” She looked at him questioningly.

“Fine,” Mel nodded.

“It’s hanging in the closet, darling. Please arrange to have it pressed. And check to see if your blue suit needs brushing and pressing,” Audrey added. She bent over Mel, by now in the taxi, and kissed him on the cheek.

Then, with a last wave of the hand, he was gone. For a moment she gazed after the car, fast disappearing into Paris traffic, then walked slowly back to the set.

Audrey and Mel were drawn together by their mutual love of the theatre. Neither one of them can detail the exact moment their friendship turned into love. “After a while, we both just took it for granted that we would marry,” said Audrey. The natural transition from realization of their love into marriage explains the fact that Audrey has no engagement ring, only a plain wedding band. “I was never engaged,” she says. “Just married.”

The Ferrers’ personal, as well as professional, interests dovetail neatly. Both highly cultured, sensitive, and intelligent individuals, they find enjoyment in the same pursuits, and each has learned to like the other’s hobbies.

Having begun his career as a dancer himself, Mel shares Audrey’s fondness for ballet as well as, of course, the theatre. Audrey has learned the finer points of jazz from Mel, who is a fervent jazz enthusiast. Their portable record player and records are always a part of their baggage.

Audrey’s interest in fashion has influenced Mel to the point that he accompanies her to Givenchy showings and helps to choose her clothes.

Mel’s zest for sports has rubbed off a little on Audrey, and she has proved an apt pupil in tennis and golf.

Both accomplished linguists, they enjoy good literature and stimulating conversation in any country in which they may find themselves.

With only three released pictures, “Roman Holiday,” “Sabrina,” and “War and Peace,” Audrey Hepburn has entered the halls of screenland immortality. The doors through which she had to pass were heavy. But they swung open before her as if by magic.

Only it wasn’t magic that did it. The only sorcery involved was Audrey’s own personal charm, which first startled and then bewitched today’s generation of moviegoers, case-hardened to a less discreet school of beauty. Audrey’s formula for success was a concoction of hard work, a strong will, and a fund of natural talents. There was a generous portion of luck, too, but even if the famed French writer Colette had not found “this treasure on the sands,” as she described Audrey, in Monte Carlo and sent her to New York to create the American version of her “Gigi,” Destiny would surely have unveiled Miss Hepburn in another guise.

The story of Audrey’s war-shattered childhood is a familiar one. After the Germans occupied Arnheim, in the Netherlands, where she and her mother were living, and closed the dance conservatory at which Audrey had been studying, she installed a dance bar in an empty room of their home. At an age when most girls are tripping over the polished floor at a school prom, Audrey was giving ballet lessons to youngsters not much younger than herself.

With the few pounds which was the maximum allowed by the post-war Dutch government, Audrey and her mother got to London. The first showman to fail under the spell of Audrey’s magic personality was the dance director of the London musical production of “High Button Shoes,” who chose her out of three thousand candidates for one of the coveted spots in the front-line chorus. Another musical, “Sauce Piquante,” brought her to the attention of British film producer Mario Zampi.

The roles that followed were small, but they brought her closer to that bright, sunlit afternoon in the lobby of Monte Carlo’s Hotel de Paris, when novelist Colette, after watching Audrey intently from the wheelchair she rarely left, cried, “I’ve found my Gigi!”

And Audrey had found her future.

“Funny Face” is a natural crystallization of Audrey’s girlhood ambitions and training. Not only does she dance in one solo star number, as well as together with Fred Astaire and Kay Thompson, but she sings.

Fred Astaire, who has had some fine dancing partners in his career, calls Audrey “a show business phenomenon.” Says he, “She can do anything and do it with spirit and verve. She’s a wonderful artist.”

Gene Loring, choreographer on the picture, insists Audrey could have become an exceptionally fine ballerina. “She endows every movement with quality and lyrical expression,” he States.

“Funny Face” employs the title of a musical Astaire did on Broadway in 1927, incorporates some old Gershwin songs and some new ones composed by Roger Edens, and has a story inspired by the true-life experiences of fashion photographer Dick Avedon. It recounts a photographer’s search for a model who embodies elegance, grace, distinction and intelligence. He unearths her, trains her, and falls in love with her.

Famed Paris designer Hubert de Givenchy, who sketched all Audrey’s dresses for “Funny Face” and who designs her personal wardrobe, calls her “the perfect model.” Says he, “I’m always inspired by Miss Hepburn when I look for my own mannequins. She has the ideal face and figure, with her long, slim body and swan-like neck. It’s a real pleasure to make clothes for her.”

Audrey’s fashion sense is also lauded by Gladys de Segonzac, “Funny Face” wardrobe supervisor. “Audrey can wear anything, with taste and dignity. And her patience in fittings is extraordinary. She can stand for hours at a time, never fidgets, never squirms. You know how tired she must be, but she never mentions it. She makes her changes with amazing rapidity, with never a wasted motion.”

Starring in a musical film is, of course, something entirely new for Audrey. Mel had been urging her to do it for some time. “And so,” she sighed, “I suppose this will start all those stories again about Mel directing my career. Of course, he occasionally gives me advice, as does every husband, but I always make the final decision myself.” Audrey’s delicately-pointed chin tilted defiantly. “I, too, felt that I needed something light and gay to follow my serious role in ‘War and Peace’,” she continued, “but in my wildest dreams, I never thought I’d have a chance to play opposite Fred Astaire.”

“I was in on the first discussions,” Mel said. “After that, I stayed out of it. I said to Audrey, ‘I don’t want to influence you,’ and I walked into the other room. Audrey usually takes about three days to read and consider a script. This one she finished in two hours. She burst into the room where I was working and cried, ‘This is it! I don’t sing well enough, and I’m not a good enough dancer, but, oh, if I can only do this with Fred Astaire!’ ”

Audrey’s passion for perfection tolerates no partial measures. Despite her background in the dance, she attended a ballet school in Paris every day for three months, preparing for “Funny Face.”

It was Paris’ coldest winter in years. The unheated studio registered sub-zero. The ballet master usually wore three sweaters; the accompanist wore woollen gloves and a heavy coat.

Audrey would arrive scantily clothed in the ballerina’s traditional black garb, and enthusiastically begin her work at the bar. She asked for no star treatment. Like all ballet students, she addressed her professor as “Monsieur,” and to him she was “Audrey,” like any of his other pupils. The only indication of her fame was the nightly inspection of the Street outside to see if the coast was clear of photographers.

This same ballet instructor, Monsieur Legrand, had occasion to judge Audrey on qualities other than her ballet skill, particularly her sense of loyalty to those she likes. On her way to the studio one day, Audrey was accosted in the corridor by a dancer who is known for her caustic tongue. “Why do you study with Legrand?” the girl asked Audrey. “I know a much better teacher.”

Audrey said nothing. After all, the dancer may have had good reasons for her opinion. But on getting to the Legrand studio Audrey learned that the dancer had never seen him work, and, as a matter of fact, had never set foot in his studio. Her remarks stemmed from pure pettiness.

Audrey was infuriated. She dashed back to the hallway to find the woman and tell her exactly what she thought of her. But she had left. Otherwise, she would have discovered how Audrey’s normal composure can melt at any evidence of injustice or prejudice, especially toward a friend or associate.

Audrey is as fierce and intense in her personal relationships as in her work. She is deeply attached to her mother, who lives in London and who often visits Audrey and Mel. Baroness van Heemstra came to Paris several times during the shooting of “Funny Face.” Her daughter’s attachment for her mother is mingled with admiration and respect for the Baroness’ great capabilities and her guidance.

Besides Mel, Audrey adores cottage cheese, milk and other dairy foods of which she had been deprived in her formative years. One of her most vivid memories of the Liberation is the seven chocolate bars given her by an English soldier. She ate them all at once, quickly, and was violently ill.

Audrey’s obsession for security is another leftover from her turbulent youth, when she witnessed the plunder of her family’s fortune by the Nazis. She has invested her earnings in such a way that she can’t touch them except in a case of extreme emergency.

“Then if I should ever get sick and can no longer work, or if I decide to retire and raise a family, I won’t have to worry about money. And I know that my mother will always be taken care of,” Audrey said soberly, as she lit a cigarette. She smokes only moderately. Mel doesn’t smoke at all, and neither of them drinks.

Although wrapped up in her career, Audrey will never become a slave to her artistic pursuits at the cost of her marriage. “We’ve been rather crafty about arranging our schedules so as to stay together,” she laughed. When Audrey laughs, she appears to be about fifteen years old.

Their first separation of more than two days since their marriage took place last fail, when they accepted their first commitments to make separate movies. Even then, the work took them no farther apart than different sections of the same country, France. Perhaps future necessities will require wider separations, but when we spoke to her Audrey didn’t want to think about the terrible loneliness she will feel during Mel’s absences. Although equipped with a fund of resources within herself, Audrey dreads solitude; and happiness, centered on one person, has become a habit. But an hour’s flight will bring them together from wherever they may be, and their love will keep them together in spirit, no matter how far apart, and no matter what the gossips may say about them.

In the meantime, Audrey will go on doing such things as lending her sheepskin-lined ski jacket to the young assistant dance director of “Funny Face,” as protection against the rigors of a French winter on location, while Audrey herself went through her outdoor routines, in the flimsy costumes of her part, without a quiver. And in such manner she will go on winning the hearts of her associates, big and small. As one French crew member was inspired to comment, “I think we should all work in our shirt sleeves. She’s cold; why shouldn’t we be?”

Audrey would have blushed with pleasure and incredulity had she heard her fellow workers’ heartfelt opinions of her. Success has not hardened her into an indifferent acceptance of kind words.

Her modesty is most apparent when she discusses her work. “I often feel so inadequate,” she said. “There is so much more I have to learn about my craft. I want so badly to be a really fine actress.”

Destiny has lighted the path and directed Audrey’s steps to the top. She is not the type to sit around and wait in idle hope for a further helping hand.

THE END

GO SEE: Audrey Hepburn in Paramount’s “Funny Face” and Mel Ferrer in Warner Brothers’ “The Night Does Strange Things.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1957

AUDIO BOOK