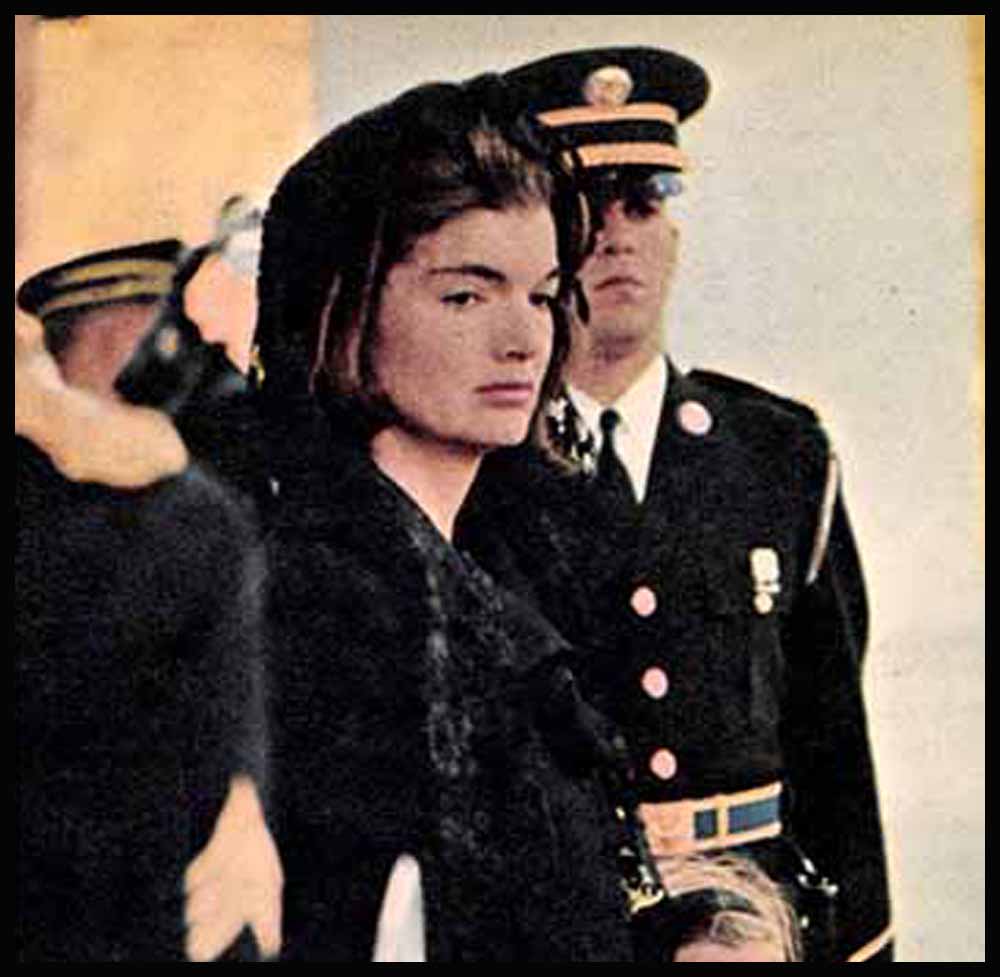

The Last Promise Jackie’s

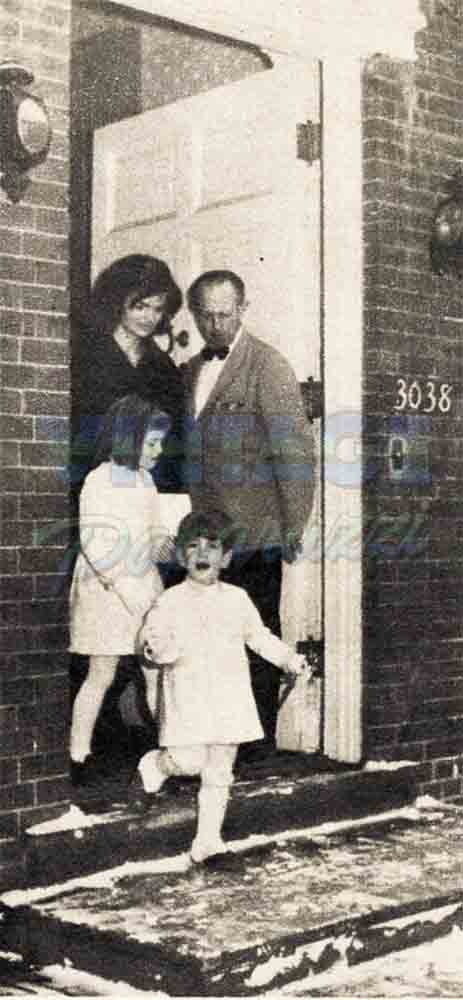

Caroline had left for school a little while earlier. Jacqueline Kennedy was alone in the library of her new Georgetown house, seated at a lovely old Federalist desk, reading the mail. When suddenly the door burst open and in zoomed three-year-old John-John. As usual, and to quote Newsweek editor Edward Kosner, an old friend of the Kennedys, “this bubbling delight raced around at a cruising speed of ten knots and a permanent list of twenty degrees.” In his hand he held a windup model of a toy jet.

Jackie stopped what she was doing and, smiling, she watched her energetic son.

“Mommy?” the boy said, suddenly breaking into her silence.

“Yes?” she answered.

“Daddy gave me this air-a- plane … a lonnnnng time ago,” the boy announced.

He continued to sputter around the room as Jackie nodded, smiling less now. “Mommy?”

“Yes?”

“Do you know,” John-John asked, “—that Daddy’s in heaven—still—for a lonnnnng time —always and always?”

And again Jackie nodded. And, difficult as it was for her, she kept her smile. And she said, “Yes…Yes, I know. In heaven.”

Whereupon the boy added, a note of awe in his voice, “And with God!” And he turned then, airplane still held high, and zoomed out of the room, leaving his mother alone again.

She sat now, the letters she had been reading temporarily put aside. And she thought now, happily, “He is not forgetting him. He is not forgetting him. And, dear Lord, give me strength, he never will!”

Oh yes, she knew, in time the so-called little things would vanish from the boy’s mind and memory. The feel of his daddy’s hand in his, as they walked together every night at seven o’clock towards Miss Shaw, the children’s nurse, who stood waiting to put John-John to bed. The sound of his daddy’s hearty laugh as they clung to one another and played up-and-down in the big swimming pool, down in the basement of the big white house where they used to live. The special and very loving look in his daddy’s eyes when he would return from a big trip somewhere, as he hopped off his helicopter or down the ramp of his plane; and, while shaking hands with all those big tali people he was forever shaking hands with, would turn—always—even if only for a moment—and sneak a wink at the little boy who stood waiting for him at the end of the long line.

Material memories would go, too—in time, Jackie knew. The toy plane would have a wing smashed one day and be dis- carded. The copy of “The Little Lost Kitten,” John-John’s favorite book which his daddy had given him last summer, already falling apart, would be in complete shreds come a month or two. The PT-boat tie-clasp that John-John was promised he could wear when he was six, and meanwhile insisted on keeping in his pirate’s treasure chest, would undoubtedly be soon misplaced. The special glass for orange juice—which always sat on the shelf next to his daddy’s—would break somehow, as orange juice glasses often do.

And so as the boy grew, so too the memories, the links with the past, with those beautiful and lost days, would fade. “But he will not forget his father,” Jacqueline Kennedy thought now, sitting there in the library of her new and husband- less home. “He—and Caroline—will not forget.”

She closed her eyes suddenly. She remembered something Jack had once told her about himself when he was a boy—words to this effect: “You’ve got to picture me as this little boy, sick so much of the time, reading in bed, reading history. reading the Knights of the Round Table, reading Marlborough. For me, history was full of living heroes. And if it made me this way—if it made me see the heroes—maybe other boys will see. Maybe other people will see.”

Her eyes remained closed. “Yes,” she thought, “—other people will see. Your children, among them, will see.”

And she promised now, so help her, that his death would not be the end of him—that he would be remembered, forever, as a living person—as a living person.

And she pledged now that her children, especially, would remember their father as a living person. And that Jack, her dear Jack, would continue to live through his children. And that through the children, she would continue to live.

And that they would never be separated from one another—not really. Because he would never be far from their hearts.

“Never. . . . ”

Her voice was soft now, but resolved.

“Never. . . .”

It was her promise and her pledge.

There was a time not too many years ago—and this is no secret to those in the know—when Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy considered herself pure Bouvier, though her married name just happened to be Kennedy. She felt herself to be French in origin and instinct. She read French history and poetry, shopped extensively at Dior and Givenchy, sought out those who spoke the “mother” language, and she furnished her honeymoon house with all manner of Louis XIV and XV antiques. One had the distinct feeling, back then, that though she had fallen in love and married an Irish-American, this was nothing more than a biological accident. Because she had, at the time, no more of a rapport with things Irish than a bernaise sauce had with a pot of corned beef and cabbage.

There was a time, too—early in her marriage—when Jacqueline Kennedy made it quite clear to the rest of the Kennedys that she had no intention of becoming “one of them” and joining in their quaint and celebrated family games—touch football-wise and others.

She was, in short, an in-law who strove hard to remain independent—and a law unto herself. And it seemed quite likely that her influence would extend, in time, to her children.

But on the death of her husband, this picture changed.

To writer Theodore H. White, shortly after the funeral, and in answer to a persistent rumor that she would soon leave the United States and travel abroad in order to assuage her grief, Jackie answered: “I’m never going to live in Europe. and I’m not going to travel extensively abroad. That’s a desecration. I’m going to live in the places I lived with Jack. In Georgetown and with the Kennedys at the Cape. They’re my family now.”

As for the “Irish question,” the aforementioned Edward Kosner recently wrote: “Suddenly Jack Kennedy’s Irish heritage has special meaning for her (Jackie). She changed the name of her new Virginia hunt-country house from Atoka to Wexford, after his ancestral county. Adding a Presidential motif—a fist clutching arrows, framed in olive branches—to the Kennedy family seal, she used the design on the cards of thanks mailed to VIP’s who had sent condolences. In a nostalgic moment with JFK’s Irish-American lieutenants, she referred to herself, with pride and gentle humor, as ‘Bridey’ Kennedy.

“Unpredictably,” Kosner goes on, “she has found special comfort in the company of these men of the Irish Mafia, that intensely loyal band of Boston pals who helped John Kennedy win the White House and served him there. Once, the ‘Murphia’ were little more than amiable strangers with whom she shared her husband. Now, they have years of precious memories in common.”

It was recently revealed that some- time after her period of mourning ends, Jackie would like to take the children to Ireland for a visit.

This may seem strange at first—and perhaps rightly—to a lot of people. When Jack went to Dublin and Wexford last year, Jackie—who was pregnant at the time, was not with him. Chances are, even if she weren’t pregnant, she’d have had no real desire to go. France with its Paris. India with its Taj Mahal, Greece with its Parthenon, Italy with its everything—yes. But Ireland, with its pubs and pretty green hedges and scarred old potato fields— why?

But after the funeral, back at the White House, at the reception for all the foreign bigwigs, dignitaries who had come to pay their condolences, Jackie spotted—among the crowd—a sweet and shy-looking young woman, plainly dressed, in her mid-twenties. When they were introduced Jackie learned that the girl was a cousin of Jack’s, who had been flown from Ireland —that very same day—in order to attend the funeral.

The two spoke briefly. For a long moment then, Jackie stared at the girl, then kissed her on the cheek. And in parting she said to the girl, “I’m very sorry I wasn’t able to visit you and the other relatives last time. But one day—not too long from now—I shall make up for it. And I shall bring the children.”

She indicated that she wanted now for Caroline and John to see the land from which her husband’s forebears had come. And to meet the good people, the descendants of those Kennedys who had remained behind back in the 1840s, but who were still a part of them and a part of their father and of his father, too.

His people are hers now

Meanwhile, Jackie sits evenings in the living room of her Georgetown house and talks with Jack’s old Irish-American friends on this side of the Atlantic—his former White House advisers Kenneth O’Donnell, Larry O’Brien, Dave Powers. And with the Irish-American family Jackie now refers to as “my family”—the Kennedys. Bobby and Ted, Eunice and Jean, mother Rose. the others.

“It’s as if,” comments a friend, “she wants to become more Kennedy herself, now that Jack is gone. So that she can raise the children to be true Kennedys. To be as gay as they. As strong. As intelligent. To be as dedicated as they to the idea of serving—one’s community, one’s nation, and one another.”

Notes another friend: “Her entire aim now seems to be to gather as many people about her who knew and loved Jack, so that his memory remains alive for her. And so that, as celebrant of his memory, she will have story upon story about their father to pass on to the children. . . . Now nothing must be lost. With the fervor of a curator, she culls the memories of those she talks with for anecdotes about her husband, especially from his White House years.”

Many of these stories will be, in time, available not only to Caroline and John-John, but to all the American people. The plan is to put them on tape, as told by the person or persons who were actually involved in the stories, and then to place these tapes in the proposed John F. Kennedy memorial library on the Harvard University campus.

This idea, by the way, is reportedly Jacqueline’s—“a unique attempt,” as someone has said, “to keep her husband’s history living history . . . personal, and vivid and of the moment.”

Some of the stories to be taped are little known—and touching. Stories of how JFK interceded for able government aides shunted aside through red tape or bureaucratic bungling. The story of how he once notified each of his World War II shipmates from the PT-109 that they, above all other men—kings and ministers and premiers and such—had ready and immediate access to his office wherever he was and whenever they needed him.

Some of the stories are humorous—like this one told by New York Herald Tribune writer Bill Haddad: “Once, not too long ago, Kennedy set out to ‘harass’ one of his Congressional buddies by calling him at just about the time the final glass of wine was being poured at a candlelight dinner. ‘Congressman,’ the President would start, ‘there is an urgent matter which has just come up.’ And then the President would launch into a discussion of some obscure piece of legislation . . . The Congressman told friends: ‘What do you do? After all he is the President, and I can’t just hang up on him!’ ”

Continues Haddad: “His light touch even filtered through to more serious matters. Once, when he needed to borrow a key man from a hard-pressed agency, he sent this wire to the reluctant top man: “ ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country’!”

Some of the stories which Jackie now collects are not so much stories as word-pictures of her late husband—among which a favorite is said to be this one, written by reporter-humorist Fletcher Knebel: “Jack Kennedy can quote from the classics, poke fun at himself, be as aloof as Charles de Gaulle or as convivial as an Irish baritone, eat gallons of fish chowder, fume like dry ice, drive a car like a fugitive from justice, go weeks without wearing a hat, read esoteric French philosophy, take three showers a day, face physical hazards without a ripple of nerves, lead others with assurance, be casually gracious, nap anywhere at any time, play practical jokes, remember a fact or a face for decades and qualify, in the words of one university adviser, as ‘a guaranteed, certified egghead.’ ”

Some of the stories are little-known sidelights on well-known incidents. Like this one which Jackie recently heard told by one of JFK’s aides—and which she may one day tell to her children in a manner something like this: “There was, once, an American girl named Marjorie. She was one of the first volunteers in a program started by your daddy soon after he became President, and called the Peace Corps. She was sent to serve for two years in a faraway country, a rather backward place but with a great pride about it.

“So Marjorie arrived there one day. And what she saw of the living conditions rather surprised her. And one night she found herself writing a postcard to a friend back home, telling the friend of what she’d seen.

“Unfortunately, Marjorie lost the postcard before she had a chance to mail it. Unfortunately, it was discovered by some students of this faraway land, who were highly insulted at what they read.

“It was a terrible time for a while. Your daddy was in an awful fix. Here was his program, his dream—so new, and for which he’d had such high hopes—but already in trouble. And here was a girl named Marjorie, who had unwittingly caused the trouble, in the middle of it now—criticized and laughed at by millions of people throughout the world.

“In time. Pm happy to say, your daddy managed to convince the citizens of the faraway land not to be offended. And in time, happily, they seemed to forget the incident.

“But Marjorie didn’t forget. And when word came to your daddy that Marjorie was very saddened by what had happened —terribly hurt herself—he stopped what he was doing. He went to his office. He picked up his pen. And for half-an-hour, he sat alone and wrote a personal letter to Marjorie.

“He wrote to her that in ali his life he had never met a human being who did not make mistakes. He asked her not to mind the critics—just as he always tried not to mind them. He told her that he had never met her, but that he had very warm feelings for her, because she had proven her true worth the day she’d volunteered to sacrifice a lot of personal pleasures so that she could go out into the world and try—as best she could—to help some people less fortunate than she. He wrote that for this alone he respected her, blessed her, and would be eternally thankful to her.”

Perhaps the loveliest of all the White House reminiscences is the one told by Jackie about the evenings she and Jack often spent together, after he’d come upstairs from a long and hard day, after the receptions and the meetings and the conferences were over, and the children were in bed, and they’d had their dinner quietly and alone together, and were ready to turn in: “At night, before we’d go to bed, he would love to play a certain record, the score from the musical ‘Camelot’; and the song he loved most came at the very end of that record. The lines he loved to hear were. ‘Don’t ever let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot—and it will never be that way again’. . . . There will be great Presidents again—and the Johnsons are wonderful to me. But there never will be another Camelot again. Never—another Camelot. . . .”

These then are the stories . . . the memories . . . just a few of the many . . . which Jackie now gathers. And which she will one day tell her children. And which the rest of the nation, hopefully—on completion of the JFK memorial library—will also get to hear.

Ali part of a pledge and promise which Jacqueline Kennedy once made, lovingly, to Jack—her husband.

And which, lovingly, she keeps.

For their children.

For us all.

—ED DeBlasio

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1964