Becoming A Father’s No Joke!

I had no idea I was going to wind up holding Mike O’Shea’s hand in a hospital corridor when I called that morning to ask how Virginia Mayo was feeling. It was just a few days (we thought) before the baby was due.

Virginia, Mike said, was “fine, just fine.” Then he issued that strange invitation: “Hey, why don’t you go to the hospital with me when I have to walk the floor? I’m gonna need some moral support!”

I was flattered, of course, and I was very much touched.

“Any hour of the day or night,” I answered. That’s when the vigil began.

AUDIO BOOK

On the whole, Virginia had a quiet pregnancy. Astonishingly so, when you consider that her house rang with the pounding of hammers and the brrrrr of electric saws almost the entire nine months; they were building a second story for the O’Shea heir. Happily, Virginia isn’t one to be more than moderately disturbed by necessary evils. The house was in chaos—so it was in chaos. She couldn’t see why the fact that she was pregnant should give her cause to complain about it. As for the pregnancy itself, as far as she was concerned it was all a slow but natural process which was undeserving of fuss.

The day the baby was born, Mike had something to say on that subject. “A lot of women,” he put it, “use their condition to get extra attention. They have to have special things; they get temperamental, and if you don’t indulge every whim they dissolve into tears. So many of ’em use it as an excuse that now everybody says isn’t Virginia terrific because she doesn’t. So what’s terrific? She’s just being completely natural, the way she’s always been.”

For once the O’Shea missed a trick. He missed the fact that remaining completely natural, while becoming a top star or a mother for the first time is kind of terrific. But that’s the way his wife is.

According to the best medical calculations, Mary Catherine O’Shea was to have been a trick-or-treat girl, born on Halloween. But she missed that deadline by a week. And then by another. And in that second long week, while her friends and family waited with baited breath, Virginia casually let it be known that she’d just as soon the baby wasn’t born for a while longer. Mike having said off-handedly, “Baby on the way, guess the old man will have to get out and go to work,” was up to his ears in assignments. During the next few days, he made the pilot film for a thirty-nine-week television series. He rehearsed and filmed a play for the Schlitz Playhouse. And, on the weekend, he made appearances on two live TV shows, one local and one national. And Virginia said firmly, “I don’t want to have the baby now. Mike would be too worried to do his best work.”

She got her wish. The baby obediently stayed put while Daddy brought home the bacon.

That local TV appearance of Mike’s took place on a Saturday night. Watching the program, I was amazed, to put it mildly, when Master of Ceremonies Peter Potter excitedly waved a message and shouted, “Mike, you have just become the father of a nine pound, six ounce boy! Congratulations!” If you happened to see that program, you have already witnessed color television, because Mike O’Shea turned at least six shades of green.

As it happened, the message turned out to be some anonymous practical joker’s idea of wit. And Virginia, it seems, when the phony announcement was made, was sitting at home, watching the program and laughing uproariously.

It was a cold, bleak Thursday morning, the 12th of November, when I checked in with Dorothy Jeffers, the O’Sheas’ girl Friday, and asked her if she thought there ever would be a baby.

“Oh, I don’t think there’s any question about that,” she laughed. “She’s going to have a baby, all right—but heaven only knows when! Mike is taking her to see the doctor this afternoon, and I believe that if nothing has happened by the weekend, they’re planning to put her in the hospital anyhow. I’ll sure call and let you know.”

She did. In a matter of minutes. “Can you get to the hospital right away?” Her voice was urgent. “Mike asked me to call.”

“Wah?” I asked stupidly.

“Hospital. Right away,” she repeated and hung up.

I fumbled into some clothes and bolted for the car. I was heading down Wilshire Boulevard toward Santa Monica when a most unpleasant sound penetrated my numbness: police siren. Impatiently, I pulled over, hoping they’d get their offender in a hurry so tliap I could be on my way. They did.

The officer was courteous. “Morning,” he said cheerfully. “See your driver’s license, please?” He saw it. “I suppose,” he went on in a conversational tone, “you had a good reason for going fifty-five in a thirty-five-mile zone?”

“Yes, sir,” I stammered. “I’m on my way to St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica. The baby’s finally coming, and I’ve got to hurry.”

He gave a long look at my waistline, and his pleasant smile vanished. “Lady,” he said as he handed me the ticket, “that’s a very flimsy story!”

When Virginia and Mike drove up, she, of course, was calm. She let herself out of the car, gently told Mike to go park it somewhere, and came smiling up the hospital steps. “Hi,” she said to me. “Are you going to miss any Photoplay deadlines on account of all this?”

At that moment I couldn’t remember what a deadline was. “Are you all right? Was the drive bad?”

“The drive was fine,” she answered. “Except that Mike got confused and started to drive to Beverly Hills . . . I wonder what I’m supposed to do now? Register, I suppose.”

The nurse at the receiving desk was horrified. “Why, Mrs. O’Shea, I’m so sorry!” she said. “I thought surely someone had registered you before you got here.” The look she gave me was a scorcher.

So it was Virginia, herself, who filled out the necessary form. She thought she might as well, since she was there and Mike hadn’t come back yet.

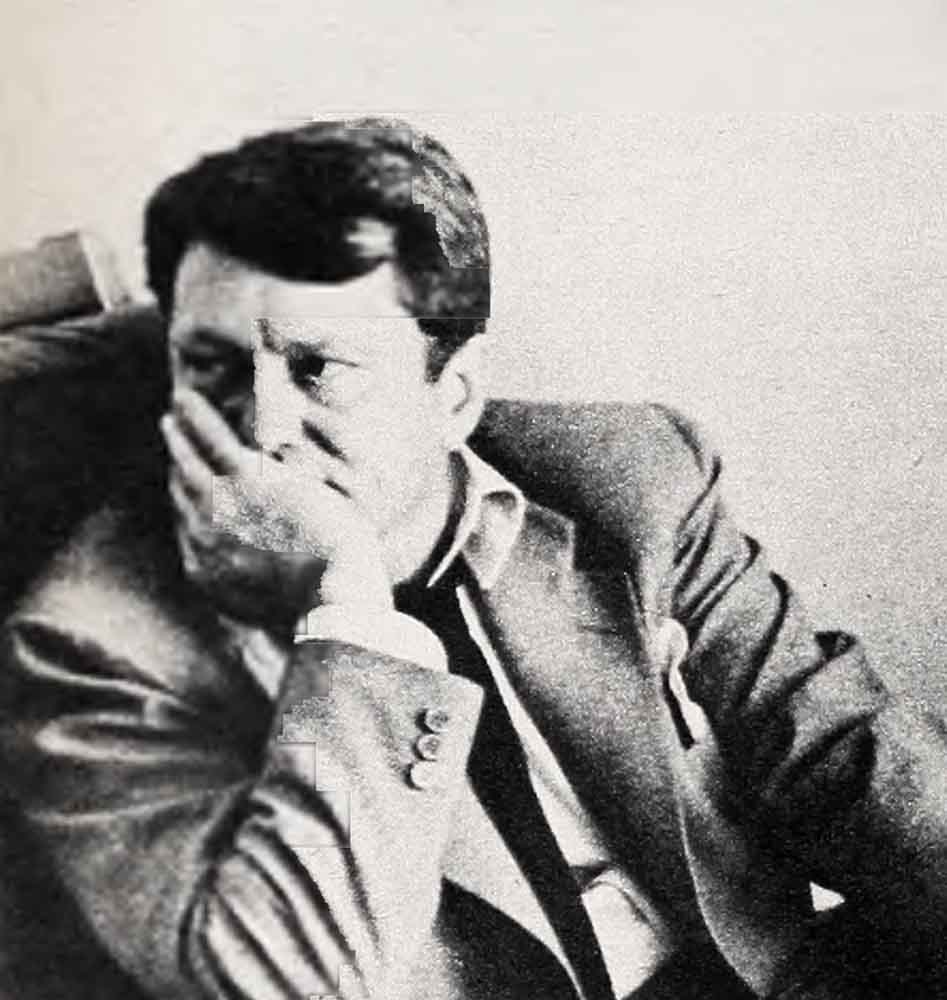

Mike was a little pale when he did walk in—and elaborately casual. He was urbane, glib, jocular. Not at all nervous. The only trouble was, you couldn’t get with him. His eyes were remote, except when they rested on Virginia. And once we reached the maternity floor, once she had gone away under the solicitous hand of a nurse, Mike didn’t track very well. He jumped from one conversational item to another. In the waiting room he sat down, shot up, walked to the hall, to the window, and back to his chair. “I’m not nervous,” he kept assuring no one in particular. No one had even asked.

In a little while, we left the hospital briefly—but only because Virginia’s doctor had suggested it. He and Mike held a lengthy conversation in the corridor, isolated words like “change” and “test” being audible, which ended in the physician’s urging, “Go on out and get a bite to eat, Mike. You aren’t going to be able to see her for an hour or so.”

The O’Shea walked over briskly. “Let’s go have lunch,” he said. “Man, I’m starved! And who wants to hang around this joint all day?”

But his mind never left that joint and the girl who had to stay behind. “First time I ever saw my old lady, I asked her to marry me,” he said as soon as we had ordered food. “No kidding. It was over at Goldwyn’s studio, where she w’as doing a bit in one of my pictures.” He hesitated, considering that word “bit” with a wry grin. “Well, I guess that’s the only thing you can call it. Goldwyn brought her out here to do ‘Up in Arms’ with Danny Kaye, somebody else got the part, and there she was, doing a bit in ‘Jack London’ with me.

“I’d been working with nothin’ but these bearded, dirty guys, and when I saw her standing on the set all by herself, it was like a breath of spring. So I walked over and said, ‘You’re the most beautiful thing I’ve seen around here in many a moon. Why don’t we ge married?’ ”

“And she said?” I prompted.

“She said, ‘You talk like an idiot.’ Well, I am an idiot and I told her so, but I said ‘Let’s get married, anyhow.’ And we did—five years later. I wanted to be sure she knew what she was getting, give her a chance to back out if she wanted to.” He was clock-watching as he talked.

When we got back to St. John’s, Virginia was asking for her husband, and Mike went into her for what seemed an eternity. He came out looking preoccupied, working at his knuckles as he has a nervous habit of doing. He told me agitatedly that the baby was in a particularly difficult breech position which, unless it corrected itself within an hour or two, would make a normal delivery next to impossible. Mike himself had known this for some time, but he hadn’t told Virginia—nor, any member of the household—for fear it would slip out. “No need for her to worry,” he said. “At least I can do that part of it.”

He did plenty of worrying in the next six long hours. Time and again I watched him straighten his tie, smooth his hair, and throw his shoulders back to walk jauntily into that room where Virginia lay waging the most primitive battle of all. She wanted him there. Time and again he came out, his face mirroring the helplessness he felt, his body slumping with fatigue. No change to report. Nothing.

If he had been just any expectant father, waiting in blissful ignorance of what went on, it would have been bad enough. But he was being as much a part of this birth as a man can be. Moreover, he was a famous actor whose famous wife was having a baby, and everyone in the maternity waiting room wanted to elaborate on the bond they shared with him. They called him by name, spoke of Virginia intimately, compared the progress of their respective offspring, and made lame jokes.

Inexplicably, there was a bumper crop of babies born that November 12. Perhaps all of those laboring women were like the wife of the apologetic little man we heard talking to his physician. “I told her it wasn’t due till tomorrow, Doc,” he said desperately, “But she said she didn’t care when it was due—she wasn’t going to have any baby of hers on Friday the 13th!”

Mike didn’t even smile when he heard that. There didn’t seem to be a smile left in him. His nerves were wearing pretty thin. After the first three hours had elapsed, he didn’t want anyone asking how Virginia was doing. And as the hours continued to drag by, he stopped coming back to the waiting room when he left Virginia Once I saw him standing back in a little alcove in the corridor, out of the sight of people, once sitting in a hall where there was no traffic. He’d have gone anywhere to be alone; the O’Shea was spooky as the sixth hour of his wife’s travail came near.

Finally, around 7:00, he disappeared entirely. A nurse said, “They’re taking her up now, and Doctor sent Mr. O’Shea down to her private room to wait for word.”

To wait. . . . It was quiet in the hospital now. The gray sky of the day had blackened with the weight of the night, the people at whose faces we had stared all day were gone—to pray, to rejoice, to eat—and nothing was to be heard except the whisper, whisper, whisper of rubber tired wheels, of rubber-soled shoes, of starched uniforms passing in the corridor.

Seven-thirty—and Mike O’Shea came down that long, long corridor. His gait was almost shambling and his face was expressionless, but his eyes were strangely bright and feverish. I stood up, started toward him and stopped; after all, a man doesn’t want people indiscriminately sharing in his anxiety and suffering.

A century or two passed while he stood there—and then you never saw a sweeter Irish smile. “It’s a girl. Born at 7:21. The doctor says I can see Virginia in a few minutes; she’s in good shape. You didn’t see my kid, did you? She passed right by here on her way to the nursery, and you didn’t even see her!”

We walked together down the hall to the nursery and stood before the glass door. Inside, a nurse was doing brisk things with a tape measure and a scale and a morsel of animation whose little pink hands and feet waved in the air. Then she turned the little pink bundle toward the window and uncovered a tiny foot so that we could read the anklet which said “O’Shea.” Then she reversed the bundle to reveal the tape on which was written, “11/12/53. O’Shea. Girl. 7 lbs., 3 oz. Length 21 in.” She unfolded the incredibly fragile and beautifully shaped hands. Smiling, she stretched out a single vivid red curl. And finally, she upended Miss Mary Catherine O’Shea to show her father that she was indeed a girl.

Even after she had been placed in her bed, Mike watched his daughter in silence for a full minute or so. Then he turned away, saying roughly, “Ah, I’ll belt her on the head! I’m goin’ to see my old lady.”

A long, long time later we stood on the steps of the hospital. Mike O’Shea’s hands were characteristically deep in his pockets, his head was back as he looked at the stars and sniffed the cool night air. “She’s in great shape,” he was saying. “Tickled to death about the baby bein’ a girl. She’s going to hit the hay for awhile now.”

Suddenly he laughed and shook his head. “My old lady . . . When we came back after lunch and I went in to see her, she asked me where we’d eaten. I told her. Then she asked what I had for lunch. I knew she just wanted to get her mind off things, so I told her I had steak and salad and spinach and pie.

“Four hours later I’m in there for the tenth time and she’s really having it rough Know what she said to me? ‘What kind of pie?’ My old lady!”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1954

AUDIO BOOK