“I Was Letting ‘Marty’ Down”

If anybody had told Pharmacist’s Mate First Class Rhoda Kemins that the sailor lying in her surgical ward at the Brooklyn Navy Yard would someday make her the wife of an Academy Award Winner First Class, she would have burst out laughing, long and loud.

Because to her he was just another serviceman. The wards were full of sailors in those days of World War II. They came and went. Rhoda was generally too busy nursing them, writing their letters, or just playing sister to them, to take any single one seriously. If she’d known then that he would go into the theatre as an actor, she’d have made it a point to avoid him. Show business was certainly not the right setting for her!

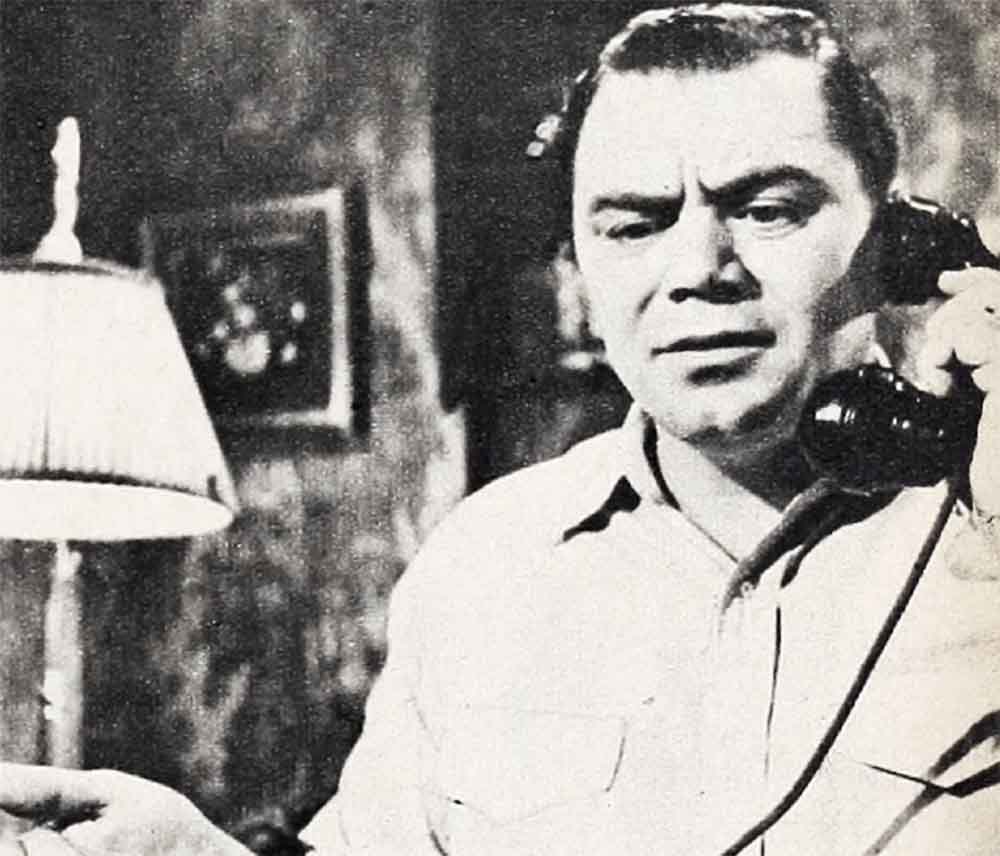

Ernest Borgnine was the sailor, and Rhoda Kemins, the plump and cheerful Pharmacist’s Mate did become his wife, six years later. It would take seven more years—years lean and hard with struggle, conflict and poverty—before her husband was to reach the pinnacle of his I acting career, and a little gold figure named “Oscar” would almost upset the equilibrium of their lives.

Today, Rhoda Borgnine is a happy woman, glowing with pride in her husband’s great achievement, quietly efficient in the role of his business manager. She speaks candidly and without self-consciousness of their life in Hollywood, her husband’s zooming career, and of what it will do or has done to their marriage.

She has made a calm appraisal of herself and is determined to, as she puts it, “fill the bill,” now that they are on top in his chosen career.

Sitting in the modest living room of their San Fernando home, Rhoda recalled that although she had always been a big girl, and surely too wholesome to be glamorous, this had never seemed a serious handicap to her.

“When I was a youngster,” she said. “I had all the self-confidence in the world. I was always sure of myself. I knew, even when I was in high school, just what I wanted to do. I was going to work at something where I’d be of service to people. I had lots of friends. I wasn’t trying to impress anybody, and if I lacked so-called beauty and wasn’t the willowy type, it didn’t really disturb me.

“I take after my father. He’s built sturdy and I’m just like him. We call him ‘The Rock of Gibraltar’—not only because he’s big in size, but because his heart is big. No matter what troubled my sister, brother or myself, we’d take it to Dad and he’d work it out with us. He did that for everybody. And he does it to this day. However, my problem, after Ernie made the grade, was something Dad couldn’t help me with. I had to work that out for myself.

“Our family is very closely knit. We had a good, full life together and it rubbed off in our dealings with others. We got along with everybody, and I was a happy-go-lucky kid. There was a club on our block in Brooklyn, just a bunch of kids from the neighborhood. We called ourselves ‘The Sterling Street Kids.’ Out of ten members, I was the only girl. And I didn’t found the club, I was invited to join.

“Those boys treated me like their sister. I heard all their troubles, they brought me all their confidences. It didn’t matter to them that I wasn’t a glamour girl.

“I had a lot of other friends, too. Not long ago, I showed Ernie my high school year book. It’s all scribbled up with dozens of names. They wrote: ‘To Dimples, Good Luck’ and ‘Love to Sunshine’—silly things that kids always write to each other in year books. The point is, I wasn’t left out of things. I had my share of puppy-love crushes, but mostly I was the big sister. This didn’t bother me. I was too outgoing, too busy playing basketball and tennis or going to movies and parties, to do any worrying.

“Like all girls, I used to dream of my ideal man. He’d be just like my dad. Understanding, loving, kind—a solid Citizen making a good salary, a man who wasn’t impressed with what people wore or how they looked. He only would want to be sure they were good human beings.

“I was raised in the tradition of the upper white-collar class, and it suited me. The kind of life where the husband has a good business and a steady income seemed the best possible life to live. That’s the way it was with my own family and with all our neighbors. Having a daughter marry an actor would have made as much sense to those mothers as having her jump off the Brooklyn Bridge!”

Rhoda’s pleasant face was suddenly illuminated by a wide grin. It was easy to see why her classmates had called her “Sunshine” and “Dimples.”

After Rhoda was graduated from high school, she wanted to study medicine, but her family dissuaded her, on the premise that it was too hard a struggle for a girl. Instead, she took a secretarial course, passed a Civil Service examination and spent six months in Washington as a typist-clerk for the government.

“After the novelty wore off,” Rhoda says, “I got restless. I still wanted to go into some sort of service. I tried to enlist in the Army, but they turned me down because I was too young. My father and I talked it over and he finally gave his consent for me to join the Hospital Corps of the Navy. I got in without any trouble and started at last to do the work that I loved.

“And I sure loved that uniform! You live in a different world when you’re in an outfit where everybody dresses alike. You keep yourself neat and keep your clothes pressed and properly tailored. You have the starched, clean-soap, well-scrubbed look, and that’s it. The word ‘glamour’ doesn’t enter the picture at all. I was so happy and comfortable in the uniform, it must have shown. I was even selected to pose for a poster, designed to demonstrate how smart we could look!”

Chief Petty Officer Ernest Borgnine had been sent to the Brooklyn Navy Yard Hospital for the removal of a spinal cyst. It was the first time in his ten years in the Navy he had ever been immobilized. And, when he first eyed Rhoda bustling around his ward, he liked what he saw.

The fact that she did not possess the classic measurements so important to his buddies didn’t even register with him. Ernie wasn’t a roistering sailor. He didn’t gamble. He didn’t drink. He believed in a wholesome, well-balanced life, What appealed to him most about Rhoda was her frankness, her ready sense of humor, her utter lack of affectation. During his two-month stay in the hospital, they dated a few times, but it didn’t spell Romance to Rhoda.

“I think he was too polite, too shy,” she says now. He was Marty in a sailor suit. He seemed kind of lost. When he was discharged from the hospital, I thought I’d seen the last of him. As far as I could figure out, he wasn’t going anyplace. He didn’t know what he’d do when he got out of service, and there wasn’t anything he really wanted to do. He had no idea where he’d settle or anything. He looked at me with those soft brown eyes and said he’d get in touch with me sometime. I said fine. I never dreamed in a million years that Ernie would turn up in my life next time—as an actor!

“But that’s just what happened. He wrote to me from the Barter Theatre in Virginia, saying he was coming to New York, and how about a date? I wrote back and said okay. I liked him a lot and I was curious to see what he’d be like. When he showed up, I got the shock of my life. He was an actor all right! You couldn’t miss it. He had let his hair grow and he was wearing a big, showy polo coat. It startled me, to put it mildly! And I was scared, too.

“He wasn’t in uniform any more. I was. We were on different levels and I didn’t understand his. He finally proposed, but I couldn’t see it. I could see marrying a doctor, a lawyer or a businessman. That would be something concrete; I’d know how to handle myself in those fields. But an actor! I just couldn’t see it.

“Somewhere deep down inside of me, I know now that I was afraid I’d never be happy in his kind of life because I’d never be able to compete with all the glamour. I just wasn’t the type. It wasn’t until years later that I realized I didn’t have to compete!

“Ernie was still very polite under all that garish wardrobe, very gentlemanly, and very persistent. He wanted to get married. He was making thirty-five dollars a week and he thought he was living! I said no as nicely as I could. He was disappointed but philosophical. I didn’t know whether I was glad or sorry. Ernie went back to the Barter Theatre, and I threw myself deeper into my work. I wanted to improve myself all I could, to better my rank. I worked so hard that I became very ill.

“I was ordered to bed for a long rest and treatment. Lying flat on my back in the hospital, thoughts of Ernie kept crowding everything else out of my mind. As soon as I was permitted to sit up, I wrote him a card. He answered by return mail and we corresponded until I got well. Then he invited me to come to Baltimore where he was appearing in ‘Hamlet.’

“I worked ’round the clock to get the time off. Actually, I wasn’t yet ready for such exertion, and when I got to Baltimore I was completely exhausted. I’m ashamed to admit this, but once in my theatre seat, I fell fast asleep, and slept through almost the entire performance! The little I saw Ernie do was wonderful. He was a great actor, even then. I thought he’d be hurt and angry when I confessed I had slept through the play, but he wasn’t. I should have known Ernie couldn’t get angry over anything as unimportant as that. He only laughed and thought it was cute. He was more concerned over my health and fussed over me like a mother hen! It occurred to me that with a man like that, a woman would never have to worry about her ego. I knew he loved me.

“We were married soon after that, in 1949, and went on the road. I loved it. I always enjoyed traveling, meeting new people, seeing new places. It was fun. I was in show business, but it wasn’t exactly what I’d expected. There wasn’t any of the fuss and publicity there is in movies. The rest of the troupe took me for granted and we were all friends. A lot of those people are still our friends. In a way it was like still being in the service. We all worked together, caught the same trains together and ate together. There was a certain amount of discipline to it, and I always function well with a set plan. The glamour I had been afraid to compete with just wasn’t there. The girls didn’t wear anything fussy any more than I did. We all wore tailored inconspicuous clothes, comfortable to travel in. They were no different from the wardrobe of any average girl who has to earn a living.”

When the play ended its run and they returned to New York, there was a change in the fortunes of the Borgnines. Somehow Ernie couldn’t find a job, and their daughter, Nancy, who is now four years | old, was on the way.

“I remember we didn’t have a nickel in the house,” Rhoda says. “I broke open a piggy bank so we could pay a few bills and buy some groceries.

“My folks helped out. They never asked any questions or suggested that my husband get out of the acting profession. That’s how they are. They accept things without any fuss. I had made up my mind that Ernie had it in him to be a success and we weren’t going to stop trying. They didn’t interfere.

“Then one day he came home all excited. He was going to take a television job, and the pay was $300 a week! After the first happy reaction to this news, I said, ‘Ernie, doing what?’

“ ‘Playing Clarabelle the Clown on the Howdy Doody Show,’ he said. ‘Just think of it, Rhoda! Three hundred a week!’

“I thought of it—for one split second. But all that clown did was honk a horn! This would ruin Ernie as an actor for the rest of his life. The money would have been wonderful, but it would only have ended in a blind alley.”

Ernie laughs now, when he remembers this incident. But he also remembers that it wasn’t so funny to him then. They needed money desperately. Ernie’s career as an actor was engendered because of an almost casual bit of advice his mother had given him after he’d left the Navy.

He had been trying all sorts of things, to find himself, and she had wisely stood by, waiting for the chance to tell him what she thought he’d be best suited for.

She asked one day, “Why don’t you try to become an actor, Ernie? I think you’d be good.”

Never having been possessed of any urge in that direction, and overcome with an innate modesty, Ernie only laughed. But that summer, he went with his mother to visit her family in Italy. She took him to the opera, to the theatres, and quietly sowed the seeds which would one day bear such sweet fruit.

Until Ernie and Rhoda married, being out of work hadn’t been a serious problem. It only meant that he’d had to pound the pavements a bit longer, pull his belt a bit tighter, and wait it out. But it was different now. He was a husband and father. As head of a household, you couldn’t just go with the tide. So that job of playing a clown looked mighty good to Ernest Borgnine. He wanted to take it for a while, to get them out of their financial difficulties. But Rhoda wouldn’t have it. So he kept on looking.

They spent a lot of time with Rhoda’s people in Brooklyn, during that period. Going there for dinner with “the folks” was the high point in their social life. High point? It was their entire social life! And it helped them to forget their worries for a while.

It took seven long years, but Ernie finally made it, just as Rhoda had been sure he would, from the minute she decided to marry him. He went from bit parts in television to small parts in plays, then a leading role in “Harvey.” One part led to another, until he was tapped for the part of Fatso in “From Here to Eternity.”

That was the turning-point in the life of the Borgnines. From that sprang the Hollywood success they know today.

And with it was born the threat to Rhoda Borgnine’s self-confidence.

They bought their first home—an unpretentious bungalow about three-quarters of an hour’s drive from the studios—and settled down to what they thought would be a simple pattern of living in their own place at last. They renewed some old friendships and acquired a few new ones. Then came “Marty.”

When the kudos started to pour in because of Ernie’s magnificent portrayal, a subtle change began to take place in their lives—so subtle, so indefinable, that neither of them was aware of it at first. Gradually they came to realize that little irritations, little differences of opinion would crop up between them, and one or the other would be hurt or disturbed. This had never happened to them before. That’s when Rhoda undertook a serious appraisal of their marriage. She wanted to be sure she was doing the right thing. After a lot of thought, she decided that she’d have to change—and make some changes in their living. But that in itself was a frightening prospect.

Because on the surface at least, things were as they had always been. At least that’s how they seemed to Ernie. He couldn’t see that their lives were different and required a slightly altered approach.

“You see,” explained Rhoda, “Ernie himself hadn’t changed. I tried to make him understand that we must make some concessions because of his success. He hadn’t the slightest idea of what I was talking about! He just couldn’t see it.

“I decided I’d have to work things out for myself. I read magazines about good grooming, I tried fixing my hair a different way, I got some clothes I thought fitted the picture of a successful movie star’s wife. I listened to advice from a lot of people. Naturally, everybody told me something different. I listened to them all. What I didn’t realize was that people think from their own personal point of view and it doesn’t fit anybody but themselves.

“I made a lot of mistakes. It irritated and upset me that I couldn’t trust my own judgment any more. I knew it was affecting my disposition.”

Rhoda leaned back and smiled ruefully. She straightened her neat tailored collar and looked out of the window, as she continued, as if thinking out loud. “There’s one thing about being big. People think you’ve just got to be good-natured all the time. They don’t believe that you can be sensitive, easily hurt.

“Take Ernie. He’s a big man. But he’s not so easygoing as you may think. He likes to have his clothes arranged just so. At night, he wants to sit in the same chair, in the same place, and watch television. He’s not too fond of going out. He’s sensitive to changes of any kind—especially in our family life.

“That’s why I couldn’t point-blank bring up this subject of getting more glamour into my appearance. I didn’t want to upset him. I wanted more than anything to think things out for myself, to get us back to normal, but I just didn’t know how. I didn’t know what ‘normal’ was for us, any more.

“After Ernie was nominated for the Oscar, all kinds of awards started to come in. We had to go to New York for one of them. I was thrilled about that. It gave me a big lift. I was homesick, I was lonely for the folks. I needed them.”

At that reunion, Rhoda and her family talked for hours. Slowly, her inner strength returned. Her sister had voiced the very things Rhoda herself had known all along—that she would never be a glamour girl, but that there were lots of things she could do: sensible, intelligently thought-out things that would make her happier, restore her faltering sense of well-being. For the first time in months, Rhoda Borgnine felt strong and sure of herself. But it took an evening in the theatre, to crystallize her new resolve.

“Ernie and I went to see a play,” she recalls. “I was happy and excited about being in New York again, going to the theatre, rubbing shoulders with people who didn’t gasp when they saw Ernie. It was like old times. I’d forgotten for the moment that the memory I expected to relive was from before ‘Marty.’

“As we walked down the aisle, I could feel the people staring at us. A thousand eyes bored into my back. all the self confidence I had built up during that talk at home nearly disappeared. I heard their whispers: ‘There’s Ernest Borgnine. There goes Marty!’ Ernie heard them, too. He squeezed my hand. I knew he was thinking that, at last, the years of hard work, of struggle, were finally paying off. But he didn’t hear the whispers I imagined: ‘Is that his wife? She doesn’t look as if she’s married to a big star!’

“Let’s face it—I didn’t. They expected a movie star’s wife to be glamorous, distinguished. I was letting them down. I had a job to do, and I wasn’t doing it. I should be wearing a mink coat. I should look well-dressed and fashionable. No matter that I wasn’t slim and sleek; I should have looked expensive. They expected it of me. That was part of my job, and to them, I had failed.

“I didn’t see that play. I watched it all right, but I didn’t see or hear a thing. all I did through that whole performance, was probe into my mind. I couldn’t figure it out. What was happening? And why should it throw me? I was the same person, wasn’t I? But, of course, I knew that wasn’t true. I wasn’t the same person at all. I was the wife of an important public figure—and I wasn’t the wife his public expected me to be.”

Upon their return to Hollywood, after that bitter-sweet trip to New York, Rhoda did a lot more thinking. She made up her mind that somehow, she’d have to carry her share of the responsibility for their new position in life. She had to convince her husband that in order to remain unchanged inwardly—which is what he wanted—she’d have to change her outward appearance.

“To Ernie,” Rhoda explained, “acting is his business and he wants to do it right. He’s not temperamental in the accepted sense of the word. He’s on top because he knows his business. I convinced him that until now it hadn’t mattered that I wasn’t the doll Hollywood girls are expected to be. But now it did. Now the public expected his wife to be special.

“ ‘When I appear in public with you, Ernie,’ I said, ‘I want to look stylish, because that’s what your public expects. That’s good for your business.’ ”

And as simply as that, Rhoda Borgnine started her own self-improvement program. She enrolled in a reducing course. She’s on a diet; she’s got a new wardrobe.

“They’re expensive,” she points out, “but they’re worth it. I got the mink coat, too. Ernie gave it to me for Christmas. It’s not important to me in itself, but I’m glad I’ve got it because in Hollywood it’s almost a necessity.

“Ernie and I know just where we’re going. We both feel that we are maturing, settling into our marriage without a lot of the wrangling and readjustment that a lot of other people in our position go through. I’m not satisfied with my personal appearance yet, but I’ll get there, slowly but surely. I’m not trying to compete with the glamour girls on the mad Hollywood merry-go-round. I’m just keeping faith with Ernie’s public—and with what I demand of myself.”

Maturity and wisdom indeed were manifest in what she said next: “A lot of people ask me if I’m jealous when Ernie makes love to another woman in pictures. I tell them that I never go to the studio to watch, but it isn’t because I’m jealous. If Ernie were a doctor or a lawyer or worked in a factory, I wouldn’t go to his place of business to watch him work, would I? And I know that, to him, making love in a play or a picture is work. I’ve got nothing to be jealous about. Ernie just isn’t that kind of a man. I don’t want to lose my husband any more than any woman does. But what so many of them don’t realize, is that there are more dangerous ways to lose a man than to another woman.

“If Ernie were in any other business, I’d feel the same way—about fitting the picture, I mean. If I couldn’t afford the things I’m fortunate enough to have now, I’d look for less expensive outfits. The important thing for any woman who doesn’t fit the average conception of beauty is to remember to forget the stylish-stout attitude! If a woman thinks young, it shows in her face. It reflects itself in everything she does. Beauty in itself isn’t important; it’s the whole frame of thought that counts. If a woman thinks she’s overweight, she is overweight, even if she’s thin as a rail! But if she needs dieting, she should face it squarely and do the job!

“I myself am guided by my doctor. I think it’s wise to get a professional appraisal and then follow orders. It doesn’t have to cost a lot of money. all a big girl has to bear in mind is that until her weight comes down to where she wants it—and even forever after that—keep away from loud clothes, heavy make-up and flashy jewelry. The simpler the general effect, the smarter she’ll appear.

“And never let go of that self-confidence! I’m Ernie’s business manager now. Unless I can keep faith with myself, I won’t be able to do a good job. But I am doing a good job now, and it brings us together. I help him study his parts. To me, it’s all very important. I just try to do the best I can with what I’ve got—and I’ve got my peace of mind back again!”

If Rhoda had been decked with diamonds at this point, she couldn’t have sparkled more as she talked of her activity, her usefulness, her future plans.

“There’s another big job I’m trying to do for Ernie,” she continued. “He’s the kind of man who isn’t happy unless he’s working. He gets moody unless there’s something to do. When he can’t stay in the house another minute, he goes down the Street to a friend of his who runs a gasoline station. Believe it or not, he helps service the cars! I’ve got to teach my husband how to relax, how to enjoy life. I don’t want him to become a member of the Hollywood Ulcers Club!”

Teaching Ernest Borgnine how to relax goes hand in hand with Rhoda’s personal betterment program. Recently, she gave him a set of golf clubs. She’ll go along to the links with him, and help use them! That’s another way she plans to cement their togetherness—and keep them both in good physical condition.

Rhoda sighed. “It’s a big struggle,” she said. “When there’s a good income, married couples get into the habit of spending money on expensive gifts. They think money takes care of everything. They forget that it’s more important and more gratifying to give of themselves.

“Ernie and I are trying never to forget that. I’m still young enough, romantic enough, and in love enough, to want the little things that mean so much to any wife. And, underneath all his touchiness about my self-improvement program, I know Ernie’s pleased. He’s accepted the idea. We’re really partners now, and I’m doing everything in my power to see it through.”

With an easy grace, Mrs. Borgnine rose and saw me to the door. She certainly didn’t resemble a Hollywood doll in any sense, but she carried herself with a kind of regal bearing and a dignity that many a Hollywood doll might envy!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1956