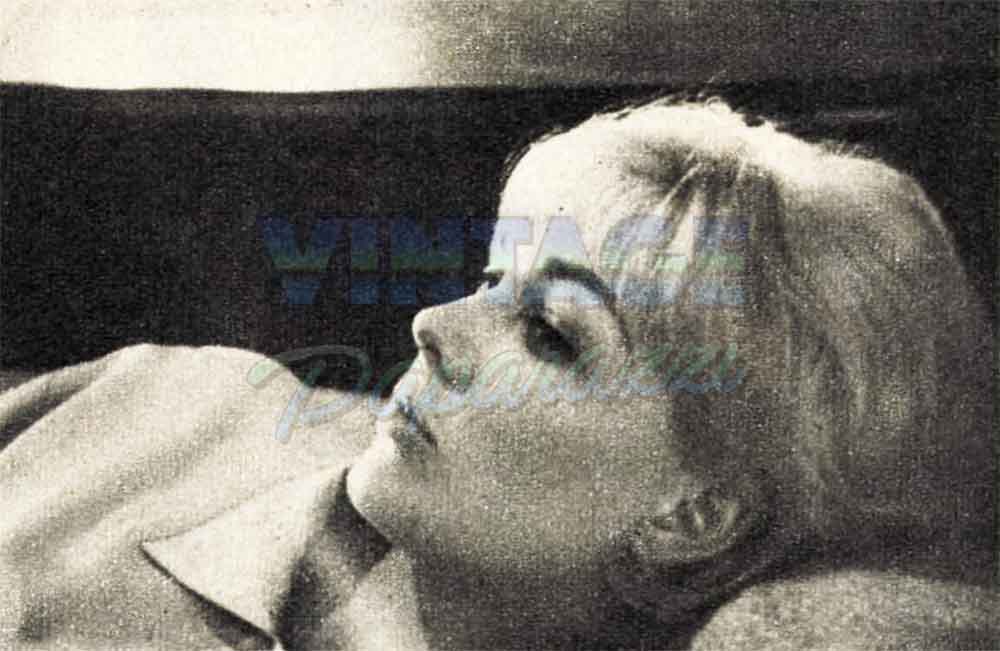

Where Kim Novak Hides From Love?

Kim Novak stood still and silent, before the long mirror in her big, fifth-floor London apartment, smiling to herself. The little Irish seamstress by her side nodded with satisfaction. “It’s beautiful,” she said. “You look lovely.” And Kim did look lovely. Most women do—in a white wedding dress. It was a white, high-necked, ballet-length dress, embroidered all over with small forget-menots. The seamstress was making it from Kim’s own design—while the film “Of Human Bondage” was still being shot outside Dublin. Now Kim had brought her over to London to finish it. Her marriage to London writer Roderick

Mann was less than two weeks away. Kim sighed as she put down the nosegay of wild flowers that had been specially made up for her by Constance Spry, the Queen’s florist.

It seemed incredible. She—Kim Novak, Hollywood’s No. 1 spinster, 30 years old—was getting married at last.

The girl who had dated Aly Khan, Dick Quine, Ramfis Trujillo, Frank Sinatra, Prince Hohenlohe and Sammy Davis, Jr., had finally found a man with whom she wanted to spend the rest of her life.

It was to be a quiet wedding. Only four people would be there: she, the groom, his best friend, John McMichael, and her secretary, Barbara Mellon. They were to be married in one of the loveliest little churches in England: St. Peter’s at Tandridge, thirty miles outside London.

Roderick Mann already had the special license. And they had both been down the week before to attend service at the church and meet the Vicar, the Rev. Field Jones. (“I had no idea who she was,” he said P later. “I just thought she was a pretty girl. To be quite honest, I was more interested in the young fellow’s motor-car—a very beautiful black sports model.”)

Kim glanced down at her engagement ring; an emerald in the shape of a cherub’s head, mounted on diamonds. They had bought it together in London’s exclusive Burlington Arcade some weeks before.

In her handbag were the news clippings that had just come in from America: “No-body who knows her believes Kim will ever get to the altar . . .” “She’s changed her mind too often in the past . . .” And from the Los Angeles Examiner: “Kim’s been almost to the alter several times and she can change her mind in a flash . . .”

She smiled to herself. This time it was different. Already London’s giant seven- million circulation News of the World had front paged the story: “Kim Gets Her Mann.” And her parents, Joe and Blanche Novak in Chicago, had given their blessing. Why, she had even written to her old boy friends, Paris designer Louis Feraud and young Bader Mulla from the Sheikdom of Kuwait in the Middle East. “I’ve met the right man at last,” she told them. And they had written back wishing her well.

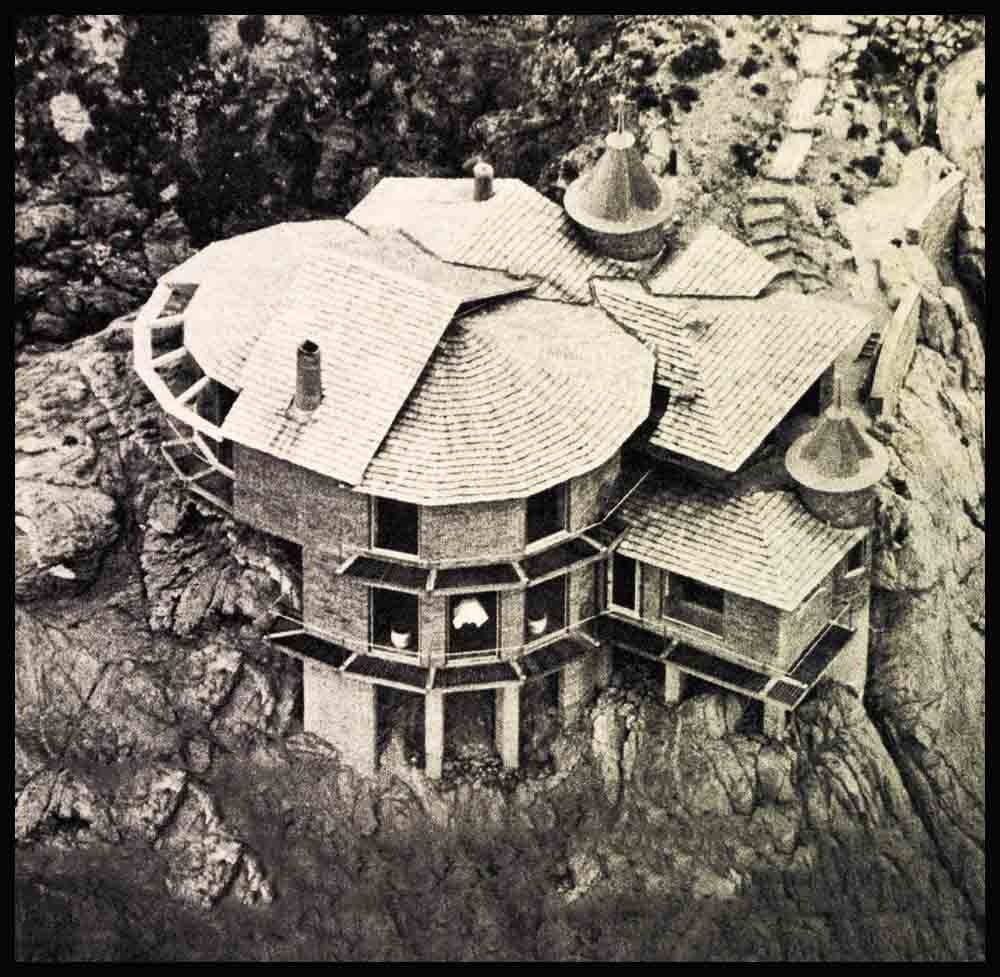

On the bed by the mirror were some hotel brochures from Jamaica. That was where the pair planned to honeymoon—at the beautiful Plantation Inn, overlooking the white coral sand and the deep blue Caribbean. Then they would fly straight to Carmel, to spend as much time as possible in Kim’s favorite home: Gull House, perched right out on Yankee Point, high above the pounding seas.

After that they would return to London. To find a house somewhere on the Thames; a place where Kim could relax and paint. far from prying eyes. Her career? She wanted to forget about films for as long as possible. “In fact,” she told friends in London, “I don’t really care if I never act again. But I hate to finish with a film I’m not happy about.”

And, although people who have seen it say her performance is excellent, Kim was far from happy with “Of Human Bondage.” She had not wanted to do it in the first place. The story, she felt, was dated. Then came the rows: first with director Henry Hathaway, who left the picture, then with British director Ken Hughes. She had not got along with Laurence Harvey either, “The whole experience,” she told a London journalist, “has been a terribly unhappy one. If it hadn’t been for Roderick I would probably have quit the picture. But he urged me to stay.”

Knowing how unhappy she was, Roderick flew to Ireland every week-end, to drive with her in the black Mark 10 Jaguar lent to her by the film company. “I have never seen two people so happy,” her Cockney driver, Joe Reece, recalls. “They were like a couple of kids. We used to go for picnics and walks, and take pictures with Kim’s Polaroid camera. It helped her a lot, having Rod there. Before he arrived I’d sometimes ring her at night and she’d be in tears, so unhappy.”

Rumors of the romance had reached the newspapers. Each time Roderick flew to Dublin there were questions. “It’s a very private thing between the two of us,” Kim told them. But she was smiling.

At every opportunity she went to London. And together they went to London’s Street markets—to buy a lamp for her Carmel house, to the famous Player’s Theatre, to quiet. out-of-the-way restaurants.

And now they were to be married. And the girl born Marilyn Pauline Novak in Chicago, and rechristened Kim by Hollywood, was to change her name for the last time.

On the face of it, everything seemed wonderful. Yet still, deep down, there were tiny nagging doubts tugging at Kim. Could one really marry and live happily ever after? She wanted to believe it, but she found it difficult.

Rod had taken her to see the Italian comedy “Divorce, Italian style”—all about the Machiavellian schemes of a man intent on getting rid of his wife. It was very funny, but it disturbed Kim. “Do you really believe love lasts?” she asked Roderick that night. “Of course,” he said. But she was not so easily assured.

One day she lunched with Roderick’s best friend, John McMichael. “I have so many doubts,” she told him. “Suppose he meets someone more intelligent than I, someone prettier? Suppose he wants to change me? I don’t want to change. It’s taken me a long time to understand who I am.”

McMichael, who had warmed to this lovely girl the first time he met her, dismissed her fears with a smile.

But Kim is a complex person. Hard to understand, even by those near her. “She has,” says a close friend, “a fantastic inferiority complex. She doesn’t think she’s attractive. She’s terribly conscious that she hasn’t got a good figure; that she has had legs. I don’t think any of her boy friends have even seen her in a bathing suit. On top of this, she feels her lack of education very much. Kim was a bad student at school—she admits it herself. And since she became a star she’s been so busy, and the pressures have been so great, that she hasn’t had time to catch up. She still can’t spell, for instance. Most of her letters are written for her by her secretary, Barbara Mellon. Probe deep and you’ll find she’s terribly aware of this.” (“I’m an awful writer,” Kim confessed in a recent interview. “I’d write poetry at school and the teacher wouldn’t even read it because my handwriting was so bad.”)

Roderick, being a writer and newspaperman, reads everything he can get his hands on. Books, magazines, newspapers. Kim never reads the papers. Reading, indeed, was hard for her. She knew this worried Roderick. Would he want to change her?

So much in common

But they had so much in common. She wrote poetry and so did he. Neither drank much, but both adored Margaritas, the Mexican drink made with tequila, cointreau, lemon juice and salt. Both liked staying home, listening to the same records (they’d played Tony Bennett’s “I Left My Heart In San Francisco” innumerable times), both liked traveling. He had been round the world. but never visited Moscow. She had. They had a great deal to talk about when together.

Of course, there were differences. She was Catholic; he was not. She had a temper like a top-sergeant’s; he was easy going. She found it difficult to talk to strangers; he didn’t.

“Part of the trouble there,” says one producer who spent an evening with them in London, “is that people expect Kim to be something she isn’t. She is not a sophisticated, poised Hollywood star. She’s a shy, rather insecure girl, very warm but very frightened. That’s why she hides herself away in Carmel. You can’t take a kid out of a middle class background in Chicago, make her a world famous movie star, and then expect her to feel secure. All the time she’s wondering when the bubble will burst.”

One night, Kim confessed her fears to Hollywood writer Lloyd Shearer, who was visiting London.

“Marriage frightens me,” she told him. “It seems to destroy love, not to enhance it. Marriage seems to turn men into heels. I can’t tell you how badly they behave, especially in Hollywood. They’re always making passes. I don’t understand it. l’m sure they were madly in love with their wives when they first married. To be honest, I can’t understand myself, either. Every girl supposedly wants to get married, yet I keep saying ‘no.’ ”

(“The truth,” wrote Shearer later, “is (hat Kim is in Jove with love, but afraid (hat marriage will alter a status quo she finds immensely pleasurable. And she is wise enough to know that a screen career and marriage won’t mix.”) It seldom does.

“Another thing,” Kim told him, “I’ve been able to travel and meet interesting personalities. The world’s opened up for me. How much of that do I give up if I say goodbye to my career and become Mrs. Roderick Mann?”

The fact that, as Roderick’s wife, she would travel even more than before and meet people from all walks of life—not merely from showbusiness—did not seem to have occurred to her. Says McMichael: “Rod draws his friends from everywhere. Go out to dinner with him and you never know who’ll be there: Bertrand Russell, Cary Grant, Tony Armstrong-Jones or ex-King Peter of Yugoslavia. He knows them all.”

With one week to go before the wedding, Kim’s nerves began failing her. She had a row with her secretary, Barbara Mellon, and sent her home on the next plane. This left her with no one to help her on the important day. Did she do this deliberately, so that she would have an excuse for delaying the wedding? Nobody knows. Maybe not even Kim.

In any event, with Barbie, her friend from Chicago schooldays, gone, Kim prevailed on Roderick to delay the wedding. She felt she would be happier if they were married in California, after all. Perhaps in Carmel, where there was a beautiful old mission.

The day before she flew home (he was to fly out later) they went to Regents Park Zoo together. She played with the seven-week-old tiger cub there, watched the gibbons at play, and then Kim and Rod took a water bus down the Regents Park Canal.

And at London Airport next day she said, “Come soon. I’ll miss you.”

But two days later the phone rang in his apartment. It was Kim. “I think you should delay coming,” she said, “I need time to think.” Roderick explained that he couldn’t delay his flight; too many things had been planned. So he flew out to join her in California.

They went to Disneyland, ate Mexican food; she showed him the house at Malibu where she had first lived when she came to Hollywood. Then they went on up to Carmel.

But it was not the same. Kim’s enthusiasm had waned. Fears and doubts had replaced her joy. Could she really give up her career? Would she be happy living in London, away from her beloved ivory tower in Carmel?

“You must remember,” says a Hollywood director who worked with her, “Kim has done it the hard way. She’s had more criticism than any actress you can name. She knows she’s not a great actress, but she is a star. And she expects to be treated like one. The trouble is, she can’t expect a man who wants to marry her to keep paying homage to ‘The Image.’ It’s the woman he wants to love. Kim has worked awfully hard to get where she is—to be Miss Novak, the movie star. Suppose she marries. All that goes by the board. There’s another thing, too, perhaps the most important thing: Kim is more aware of her failings than anyone else. She’s afraid if she marries and is exposed to day by day examination by a man, he’ll be disappointed in her and take off. That’s why she keeps talking about living in separate houses when she’s married. She’s afraid of being found out. And that’s why I don’t think she can ever dare to marry.”

A barman friend of Kim’s, who works at one of the restaurants near Carmel, told me: “It’s more than just coincidence, you know, that so many of the men Kim has dated have been married: Trujillo, for instance; and Louis Feraud; and Alfonso Hohenlohe; and most recently, Bader Mulla. Remember, even Dick Quine was married when she first met him. I think Kim chooses men like that for one reason. She doesn’t want to get herself in a position where she can get married. She once said: “I think love is wonderful, but one doesn’t have to get married just to prove it. I believe in being free. And I like contrast in men. I want to go on ringing the changes.” She said something else, too. I’d asked her one night if she wasn’t afraid of becoming thirty alone. And she said—I’ll never forget it—“Is there anyone more alone than a woman going into the thirties married to the wrong man?”

And so, there in Carmel, on the great craggy rocks she loved to clamber round. watching the endless sea, Kim’s romance finally foundered. Roderick Mann flew back to Hollywood, then to New York. On the way back to London he stopped off in Jamaica, the island where they were to have honeymooned.

He sent her a card from his hotel—the Plantation Inn.

—By JOHN MARRIOT

Kim Novak soon appears in “Of Human Bondage,” M-G-M and Seven Arts film.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1964