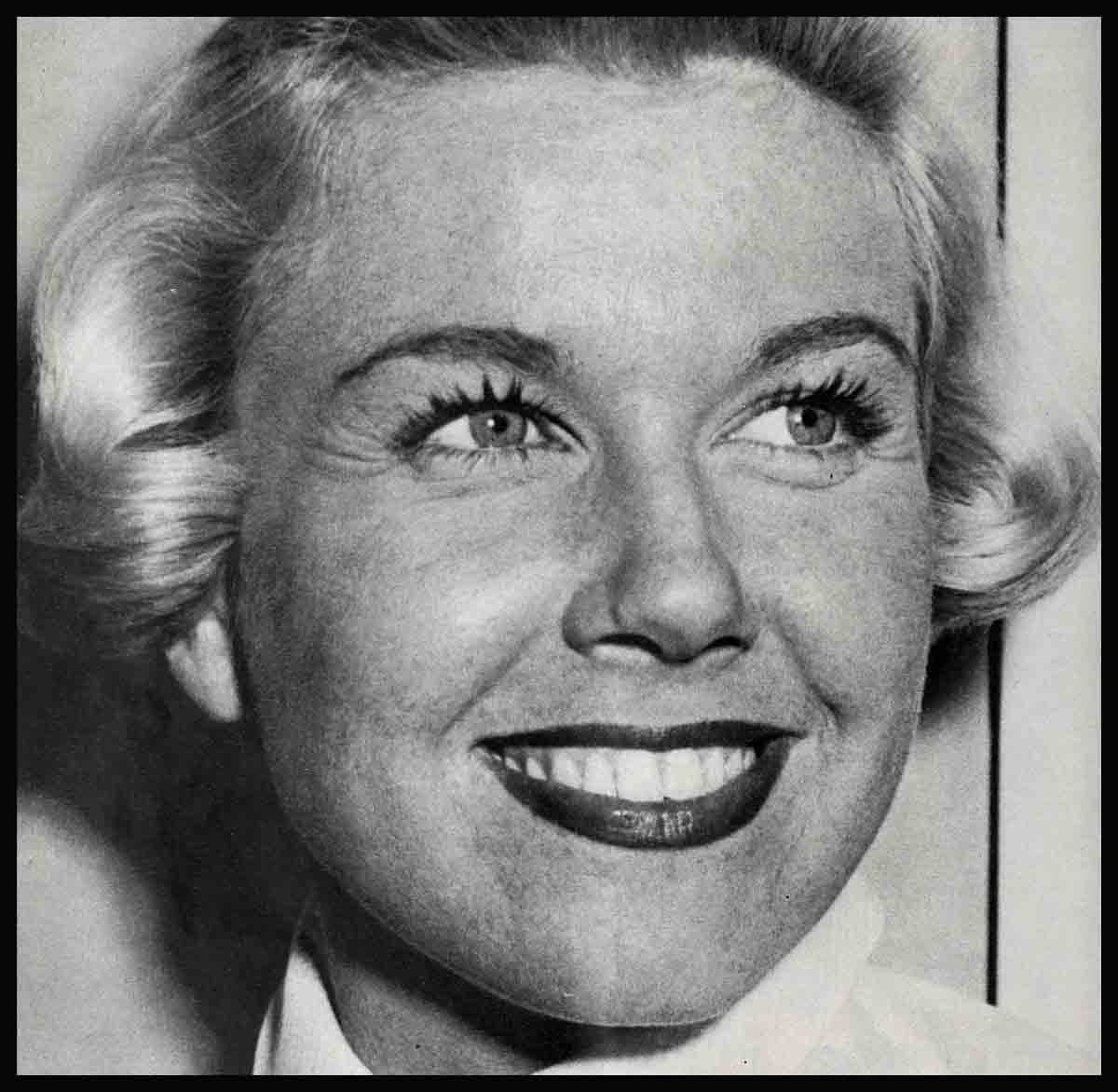

It’s A Big, Wide Wonderful World!—Doris Day

The tour of Warners’ Burbank Studio was over, and the visitor left the sound stage with his host. His grin might have stretched the miles to Culver City, if his ears hadn’t been in the way. “Beautiful afternoon,” he said, as the smog swirled down around him.

‘The studio representative smiled. “You’re still under the influence of Doris Day. I can tell.”

“There’s something about her that gets you,” the guest admitted. “Maybe it’s her smile that makes you feel good. That girl’s so happy, it’s downright contagious!”

Doris is happy these days. She knows it. She is willing and eager to talk about it. She wants to share it because she’s grateful. She knows, too well, the feeling of unhappiness.

When Doris came to Warners as a comparatively unknown singer a few years ago, she was facing the fact that her unsuccessful marriage was breaking up. Even with the great new opportunities unfolding for her in her work, she was wretched. Doris wanted a good marriage more than anything else in the world.

It could follow from this that her new happiness flows from her recent marriage to Marty Melcher, but that wasn’t exactly the order of things. “I could never have found Marty,” she will tell you. “No girl as mixed up as I was can ever find the right guy without first making some fundamental re-evaluations of herself, or life itself.”

Although Doris had known Marty for years—he had been her business manager and good friend—their friendship blossomed into love only after she began growing up. First she had to learn that it was silly to strike out belligerently against a “hostile” world—that you had only to sit back and take it easy and be grateful and that same world suddenly was peaceful and serene.

Marty put it to her straight one night when they were driving through town, watching the faces in passing cars—the frantic, worried, rushing-somewhere faces. “Good Lord,” he said, and not irreverently, “if they’d only stop and think. There they go, always in a hurry, always feeling sorry for themselves over every little thing.”

“There they go,” Doris thought, and found herself adding that old, old phrase, “and there but for the grace of God. . .”

There might have gone Doris Day, but now it was different. With Marty, she could stop and think—and live. Here was her long-sought happiness, a thing called love.

First, however, it had been necessary to learn the lessons that were to prepare her for her life as Mrs. Marty Melcher.

The change in Doris was internal, “in my head,” as she puts it. There should be a dramatic phrase to describe any process with such dramatic results as are visible to anyone who has known this girl “before and after.” She is relaxed, confident, more beautiful than she ever was, shining with an inner light. But Doris, characteristically, understates it: “I changed,” she says, “because, at last, I learned to think positively.”

To “have everything,” she had first to know that one can—and should—have everything. And she applies this to everyone. “You don’t have to depend on anyone else for fulfilment; happiness comes from inside.”

Unhappiness, too, Doris insists.

“Look at the unhappy people you know—the discontented self-pitying people putting a premium on the unattainable, wanting always something that someone else has (I know, because I was the same way); the frightened people who read in the paper about some new horror men have invented to destroy one another and stop living today because they’re so terrified of tomorrow. They’re victims of their own envies and fears and hostilities,” Doris says, “and they needn’t be.”

Her own emancipation has convinced her. “We’re so unsure, sometimes, of what we really want, and so blindly ungrateful for what we have.”

Doris had a career—she wanted a solid marriage. She doesn’t believe she was ever a real career girl. She sings and dances—and always has—for the fun of it. If she didn’t like making pictures she’d quit, no matter how much it cost in money and material things.

“I wasn’t always that smart—that honest, rather,” she confesses. “I used to believe that one had to ‘make good’ no matter how unhappy one grew in the process. I know better now.

“Now I think anyone who doesn’t enjoy what he is doing should make a change. We don’t really know what life is unless we can enjoy it. We weren’t put here to have trouble and strife. Life should be wonderful, and is.

“But so many times we keep on doing something we hate, something we’re not right for and which is not right for us, pushing and straining and never quite succeeding.

“And then, perhaps, we’re fired—or divorced—and instead of being grateful that we’re free—we feel defeated, perhaps even betrayed.”

Doris has known what it meant to be unhappily married—and fired. She was a vocalist on a popular radio show when the agency politely announced that she was being “replaced.” “But let’s face it,” she says, “I was fired.”

Now she realizes that it was the best thing that could have happened to her. At the time, she was heartbroken. Her pride was hurt. A good friend talked with her when she was most downhearted. “Don’t you know,” she asked her kindly, “that man’s extremity is God’s opportunity?”

“I know now,” Doris grins ruefully. “We’re stubborn creatures though. Seems to me that God has to shove us and shove us before we’re willing to let Him have a hand at straightening things out. And we don’t even have the decency, sometimes, to be grateful when He does. I thought I was being pushed around, when I was being guided.”

Doris was thinking differently about things before Marty Melcher loomed in her life as the one man she had been looking for during all those years of confusion and unhappiness. Otherwise, she admits, she never would have known he was the “right guy.”

With Marty, she says, every area of her life is miraculously easier. She used to worry about the “problems” of her young son, ten-year-old Terry.

“Little boys,” she recalls, “can get into some big fights. They fuss and they fume, and they end up not speaking to one another.

“Terry used to come home occasionally bristling with his grudges, storming ‘I’m never gonna play with him anymore!’

“And how did he end up? Sitting at home alone. It worried me, and I told Marty about it.”

The next time it happened Marty took Terry—who adores Marty, happily—right back outside, found the current enemy and sat them both down together.

“Now,” Marty told them, “we’re going to held court. You can tell me your side, and then Terry will tell me his. You’re your own lawyers, see—I’ll be the judge.”

The kids enjoyed playing court so thoroughly that they forgot to be mad—and Judge Melcher soon was able to slip away unnoticed.

“There were only one or two crises after that,” Doris says, “and then, I think, only as a lure to get Marty to come out and play again.”

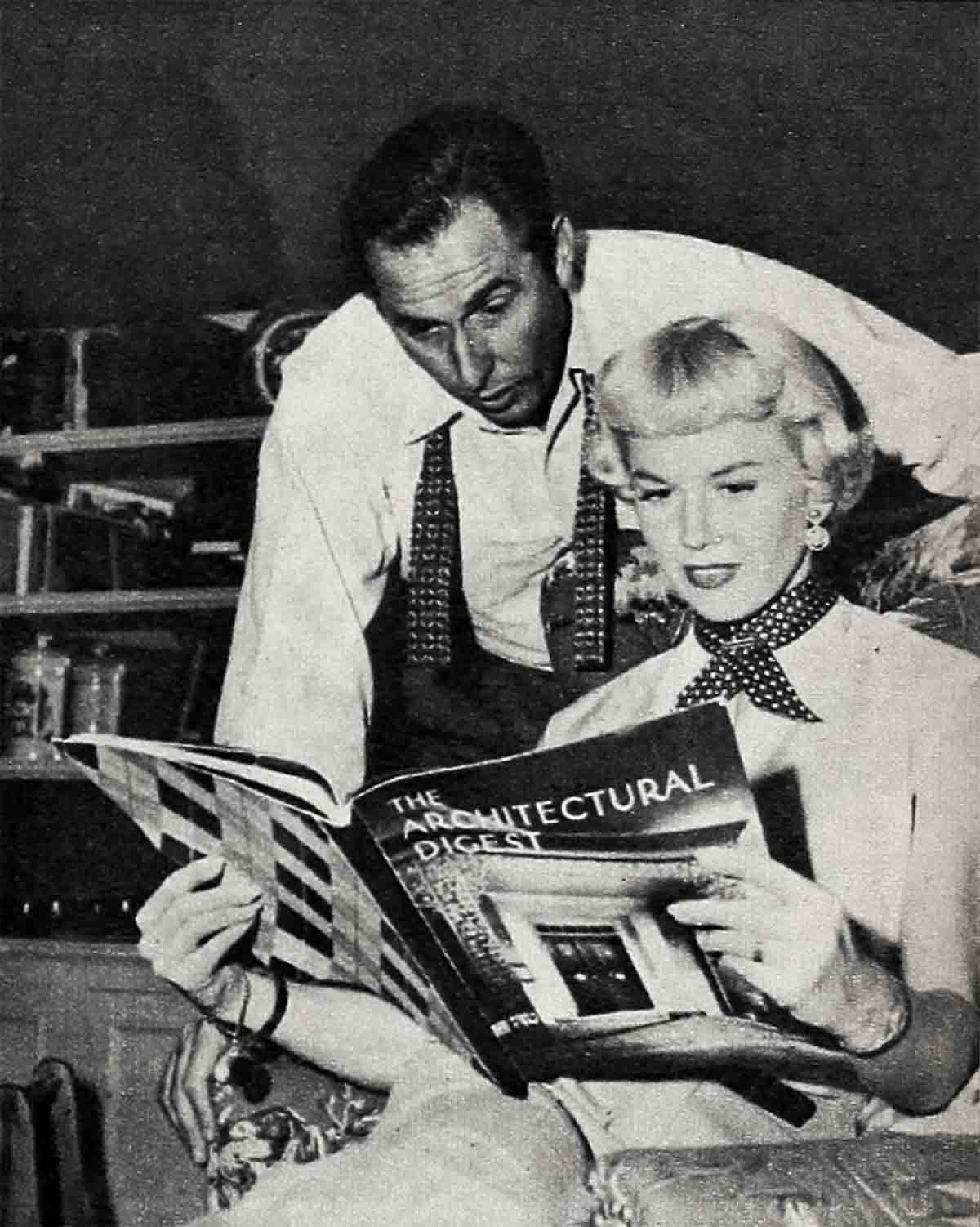

The Melchers had another their new house. “It’s always about the little things,” Doris confesses.

Soon after their marriage they moved to a big, homey Colonial house only two blocks from the studio in one of the Marty-inspired moves to make Doris’ double life—at home and on the set—as pleasant as possible.

They proceeded to redecorate—the walls downstairs had been a deep green which they found depressing. Doris proceeded to choose a paler blue shade and supervised the painting herself.

Horrors! The blue was even worse than the green.

“It’s the house,” Doris wailed. “I just don’t like the house!”

“It’s not the house,” her gently. Marty reminded her gently. “Remember, it’s all in your head.”

So they called in a professional decorator, Catherine Armstrong, who proceeded to turn the place into the embodiment of their fondest dreams of home.

“And we made a wonderful new friend in Catherine—as if the beauty she created weren’t enough.”

The major rooms of the house are being decorated in the French provincial period with the principal color a warm, friendly bisque, with accents of cranberry and turquoise.

The porch overlooking the garden is being glassed in for a playroom, which will be furnished with the Early American pieces Doris had collected before her marriage.

“It’s big and informal and is going to be just great for the children,” she glows. And then she catches herself, blushing like a teenage school girl. I mean the child.”

She feels like a child herself sometimes, a happy child. Marty—he says so himself—“spoils her rotten.”

Actually, she amends this, he spoils her “Just a little bit,” and she loves it. But “I try not to take advantage,” she says.

Almost every day, they find new reasons to be grateful, and their happiness together grows with their growing capacity for gratitude.

They went out to dinner one Sunday night not long ago, way, way out in the Valley to the home of a friend of Doris’ brother.

The people weren’t in show business. They’d built a lovely home practically with their own hands.

Marty found out that their host’s job took him into the heart of the city every working day.

“Isn’t the transportation pretty rugged?” he asked the man, for he knew the family had no car.

“It’s a little rough,” the host admitted. He got up every morning at five, and left the house before six. He had to make connections with two busses and a street car to get to the office by eight o’clock.

Besides, his transportation nipped the family budget for five dollars a week in fares. It was a little rough.

“And I’ve been squawking because I have to get up at seven and drive two blocks in a luxury car to get to one of the most exciting jobs a girl could have,” Doris told Marty on the way home.

She hasn’t passed a bus stop since without feeling grateful, and just a little bit ashamed of herself.

Last Sunday after returning from church, the Melchers felt like seeing some people, so they called a few close friends and urged them to come on over. The house is still in the process of refurbishing, and there was no place to sit inside. So they pulled some easy chairs out onto the grass in the back garden, and sat there for hours.

“It was so pretty,” Doris says, “and so cool with the breeze from Toluca Lake.”

It couldn’t have been a less exciting afternoon, really, and yet Marty and Doris felt, when the sun had set and the guests had gone, that this had been a really perfect day.

“No one could possibly be unhappy on a day like this,” Doris sighed. “No one could look at the beautiful colors of the flowers, the new green of the grass coming up, no one could watch the birds fly and still not know that life is beautiful and wonderful and good.”

THE END

—BY PAULINE SWANSON

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1952