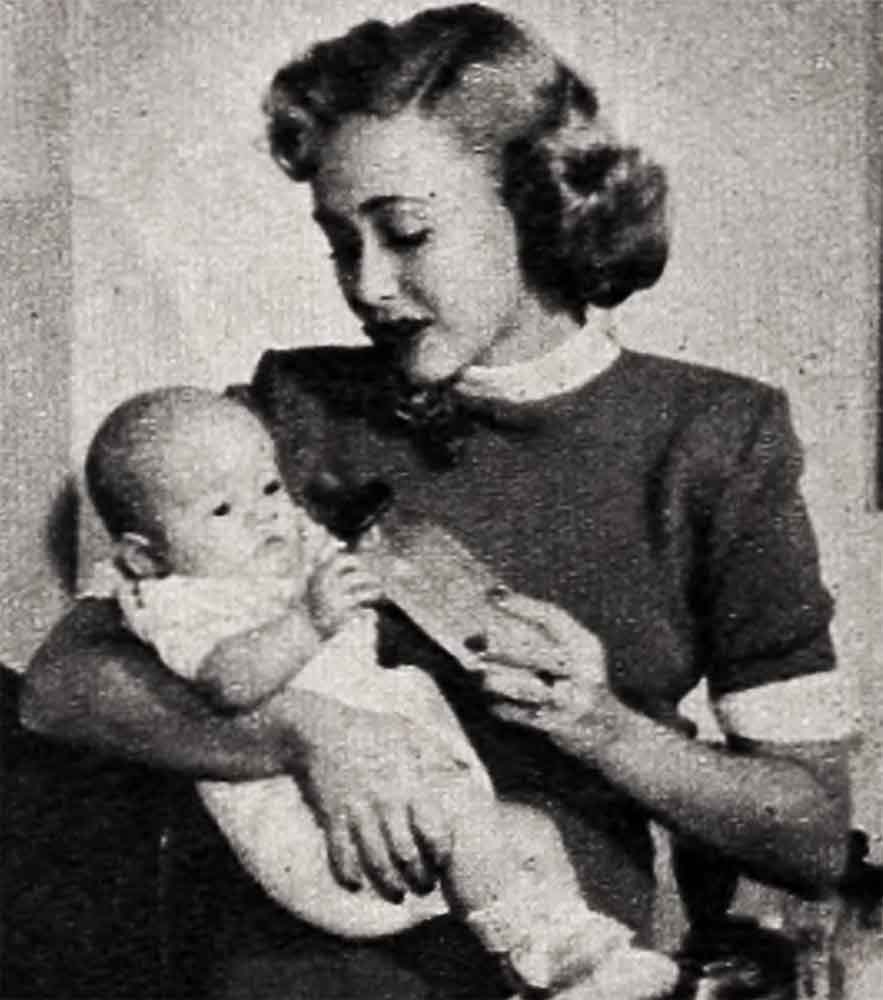

Backstage Baby

Geary Steffen crooked a finger at his baby’s button nose, touched it gently and said “Boo!”

Over her shoulder, Jane Powell Steffen gave the two men in her life an indulgent smile and went on tidying up her dressing room at the Chicago thea-making personal appearances. Geary crooked his finger again with the same result. The baby’s eyes just opened wider. “Isn’t he ever going to learn to smile?” Geary wanted to know.

Woman-wisdom of the ages dictated Jane’s reply. “He will. As soon as he’s old enough.”

Geary’s strong -hand cupped Geary III’s tiny head and he ruffled the silken fuzz. Holding a strand to the light he examined it closely. “Honey,” he said, “I’m afraid this kid is going to have red hair!”

The slight tinge of alarm in his voice brought the attention he wanted. Jane crossed the room, gave his own blond thatch a playful tug and said, “For goodness sake, silly, the baby’s hair isn’t red, it’s light brown. Most babies have hair this color. Just like they have blue eyes at first.”

Sure?” he asked.

Certain,” she replied. “Your mother says yours was exactly the same shade.”

A million young parents have played the same scene exactly the same way while getting acquainted with that amazing creature, their first-born. Yet here there was a difference. Up the theatre stair-well came a bellowed warning, “Haaaaalf hour!”

Jane’s voice was matter of fact but her eyes turned back for another fond look at her husband. “Honestly,” she remarked, “I suppose I’m being foolish but do you know, I hate to leave the baby for even the few minutes I’m on stage?”

With a rustle of taffeta, she ran down the stairs. Geary smoothed out small blankets and remarked, “There. I guess he’s comfortable. This fellow is overdue for a nap.”

But this fellow manifestly had other ideas. Small clenched fists fought their way out of the covers. Geary covered him up again. “Hi, Socker, no fair. You’re supposed to go to sleep.”

The baby continued to demonstrate how he had earned his first nickname. As fast as his father could tuck in the blanket he worked his hands free.

Geary shook his head. “The kid’s got me licked. He’s used to Janie singing him to sleep and I’m no Janie.” Then the spark of an idea kindled. “Say, do you suppose I could take him into the wings? I’d sort of like to hear Janie myself.”

Spreading out a blanket he folded his son into a snug cocoon and arrived in the wings just in time to hear Janie confiding to her audience, “All you mothers have sung this song at some time or another. It’s all about a curly-headed baby. But I don’t want to deceive you. I want you to know that my baby hasn’t a curl on his head. All he has now is a light brown fuzz.”

The enthralled audience gave a happy sigh. The baby, recognizing Jane’s voice, turned his head. As she crooned the lullaby his eyelids drooped and before she had taken her last bow, he was sound asleep.

Thus Geary Steffen III, at the age of two months and one hour, became, on the stage of the Oriental Theatre in Chicago, the latest inheritor of an ancient theatrical tradition of being cradled in a trunk.

Stars just don’t take their small children on tour any more. When they are on the road, their offspring are left at home in charge of a trained nurse.

In the eyes of Janie and Geary, such an arrangement was strictly no good. Yet there is no denying that when the question of a personal appearance tour came up, it forced into sharp focus a problem which Geary and Jane share with many ether young couples: Should Jane choose work or motherhood as her true career?

Motherhood took precedence over work, but they’d choose both it they could make it practical.

The roots of their decision went back to their basic attitude that having children is an enriching human experience and they credit Dr. Bill Caldwell, Joan Leslie’s husband, with crystallizing it.

Geary explains, “Bill’s not only a great obstetrician, he’s a wise friend. He understands the strong emotional drive which makes a person a star. He knows that if you try to bottle up talent, it just ends in an explosion.”

Geary rigged up a phone system that ran from the baby’s crib to a loud speaker at the side of their own bed. They were able to hear every slightest move that Socker made. One night Jane put it at her side of the bed and on the next night Geary had it beside his pillow. In that way one was always “on duty” to attend to changing and feeding and the other could get a good night’s sleep.

One thing about this system bothered Janie. When Geary asked the usual morning question: “How was Socker last night?” she often replied, “Oh, he was sort of fussy.” Or, “He wouldn’t take all of his bottle.”

But when it was the other way around Geary answered heartily: “Everything was just fine. Just wonderful. Just great. He didn’t give me a bit of trouble.”

Janie furrowed her brow and brooded a little about this. Then one morning she inquired, “How does it happen that I always seem to get Socker on his bad nights while you get all the good ones?”

Geary shrugged in a big way. He said, Well, I’m just lucky, I guess. Or maybe it’s because we boys get along better. That’s it. Man to man we just seem to understand each other.” Then he ducked and ran to avoid the pillow that was flung.

Geary was aware that Jane was getting restless. Having been in pictures since she was thirteen years old, the habit of working was deeply ingrained. On Geary’s return from work one evening, Jane greeted him with a solemn face. “I called today and my picture is being postponed. Gosh, I don’t know what I’m going, to do. I’ve been shut up in this house for nearly ten months now, and it’s getting me.”

The next night when he came home, Jane had further news for him. “My agent, Paul Small, has an idea. Pie wants me to go on a personal appearance tour. What do you think?”

For an hour they weighed the pros and cons. Geary settled it by saying, “Let’s call Bill and find out what he thinks.”

“If you feel strong enough, it’s okay,” Bill decided. “But use your head about it. Get to bed early. Rest between shows. No benefits or other outside activity.”

That’s when the commotion really started in the Steffen household, with Janie, the actress, in conflict with Janie, the wife and Janie the mother.

To Geary she wailed, “I’m going to call the whole thing off unless you can come with me. I just don’t want to go alone.”

In a business manner, Geary sat down and studied her proposed itinerary. He had insurance matters he could attend to in Chicago. New York, too, would fit into his plans. Buffalo and Cleveland—no. They worked out a compromise. Where Geary’s work fitted into the schedule, he’d be along. “It’s a good plot,” he concluded. “Also I’ll be back home part of the time to help Gladys with the baby.”

Janie gasped, “Why, I can’t leave my baby! I just got him.”

Geary threw up his hands. “You want to go on tour, and you don’t want to leave the baby. Janie, darling, once and for all, make up your mind.”

Janie did, in a typically feminine way. “Why den’t I just take the baby along? Actresses used to do it all the time.”

Applying his usual rule of reason, Bill Caldwell said, “I don’t see why not. The kid is perfectly healthy, you’ll give him the same care on the road that he gets here.”

Not having sung for ten months, Janie was afraid she was rusty. Her vocal coach, however, listened to her and beamed. “It’s just like with Schumann-Heink. Having a baby has been good for your voice.”

As the packing went into its last flurry, their friend, Barron Hilton, of the Hilton hotel family, took over. He made certain their suite would be exactly right when they reached the Palmer House in Chicago.

According to plan, Jane and Geary came on ahead. Gladys and the baby were to fly in two days later, after Janie was over the excitement of her opening.

Arriving at the hotel, they found a bottle warmer in the kitchenette, the makings for formula in the refrigerator. But at the sight of the crib, Jane grew misty-eyed and Geary admits he swallowed hard.

“But we didn’t telephone home right away,” he says. “We knew the baby was perfectly all right with Gladys. So we waited twenty-four hours—when we just couldn’t stand it any longer.”

When Geary III finally did arrive, even though he was never actually brought onto the stage, he came close to topping his famous mother in popularity. Janie hadn’t really intended to take him to the theatre at all, but playing six shows a day she didn’t have time to return to the hotel between performances and she just couldn’t bear being separated from him.

The public, discovering somehow that the baby was in the dressing room, clamored to see him. They jammed arcund the stage door in such numbers that Geary and Jane, fearing Geary III misfit get hurt in the crush, had to leave the theatre by a circuitous route which led into a tunnel, through the kitchen of a restaurant.

To Jane and Geary their Chicago visit always will be a milestone as the place where the baby learned to smile, to flop over in his crib all by himself, and to crawl.

Jane, modest about his achievements, protests it isn’t really crawling. Geary contradicts. “It is, too I put him on his tummy, he sticks his feet in the air, and then when I flatten my hand against them, he straightens his legs and inches forward. What do you call that if it isn’t crawling?”

But such memories, treasured as they are, are overshadowed by the fact that they found during the personal appearance—with baby—confirmation for the plan of living they had set for themselves.

“We know now,” says Geary, “that Janie can continue working as long as she happens to want to. The only difference is that when she’s having a baby she won’t be able to be in a picture.”

Then he grins. “Come to think of it, maybe that means she’s going to miss quite a few. This young fellow of ours will face plenty of competition.”

Janie nodded happily. “He’s going to have five brothers and sisters. We made up our minds we would have six children, even before we were married.”

They’re smart, Janie and Geary—smart with heart!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1952