Who Needs Men?—Debbie Reynolds

Have you ever seen perpetual motion? Ever had lunch with a windmill? Meet Miss Debbie Reynolds.

She zips into the restaurant like the devil himself is behind her, because she’s late and punctuality is a habit of which she approves. The tardiness today isn’t her fault. Over at MGM the cast of Athena broke late for lunch. That’s all. You get no effusive, movie star apology from Debbie. She gives you a quick grin and that direct, green-eyed glance of friendliness as she slips into her chair and picks up a menu.

She looks it over, but she’d rather talk than eat. As a matter of fact, she never stops. “Have you ordered? What’ll I have? Let’s see—no, I’d better not have that. I have to dance this afternoon. The fruit salad. Yes, fruit salad.” The imp disappears; now she’s a wistful little waif, turning large, appealing eyes up to the middle-aged waitress whose answering smile is fond but not fatuous. “But could I have more pears or something in it instead of grapefruit? I hate grapefruit! Now, what to drink?”

“Milk,” chorus her companions.

“Nnnnnnnh,” the pert nose wrinkles indecisively. “I’ve already drunk about two gallons on the set this morning. I’ll have to think about it and tell you later. Big decision.”

Food disappears from her mind with the retreating back of the waitress. “How do you like my new skirt. It’s full and blue, with an all-over pattern of spools. “Mother made it. And she found some buttons made of tiny spools, and we’re going to put them on a blouse. And then I’m going to cover a handbag and sew spools all over that. The living end, isn’t it?

“Lori Nelson and I are going to open a shop in the valley with ideas just like this. Well, it’s really our mothers who’ll do the work, but they’re the ones who want to do it. You know, my mother makes all my clothes and my grandmother sews, too. Then, Mrs. Nelson makes lots of Lori’s things and her grandmother sews. We have to talk to our business managers, though, and see if we can afford it. We’re going to call the shop Lori-Debs. Pretty cute idea?”

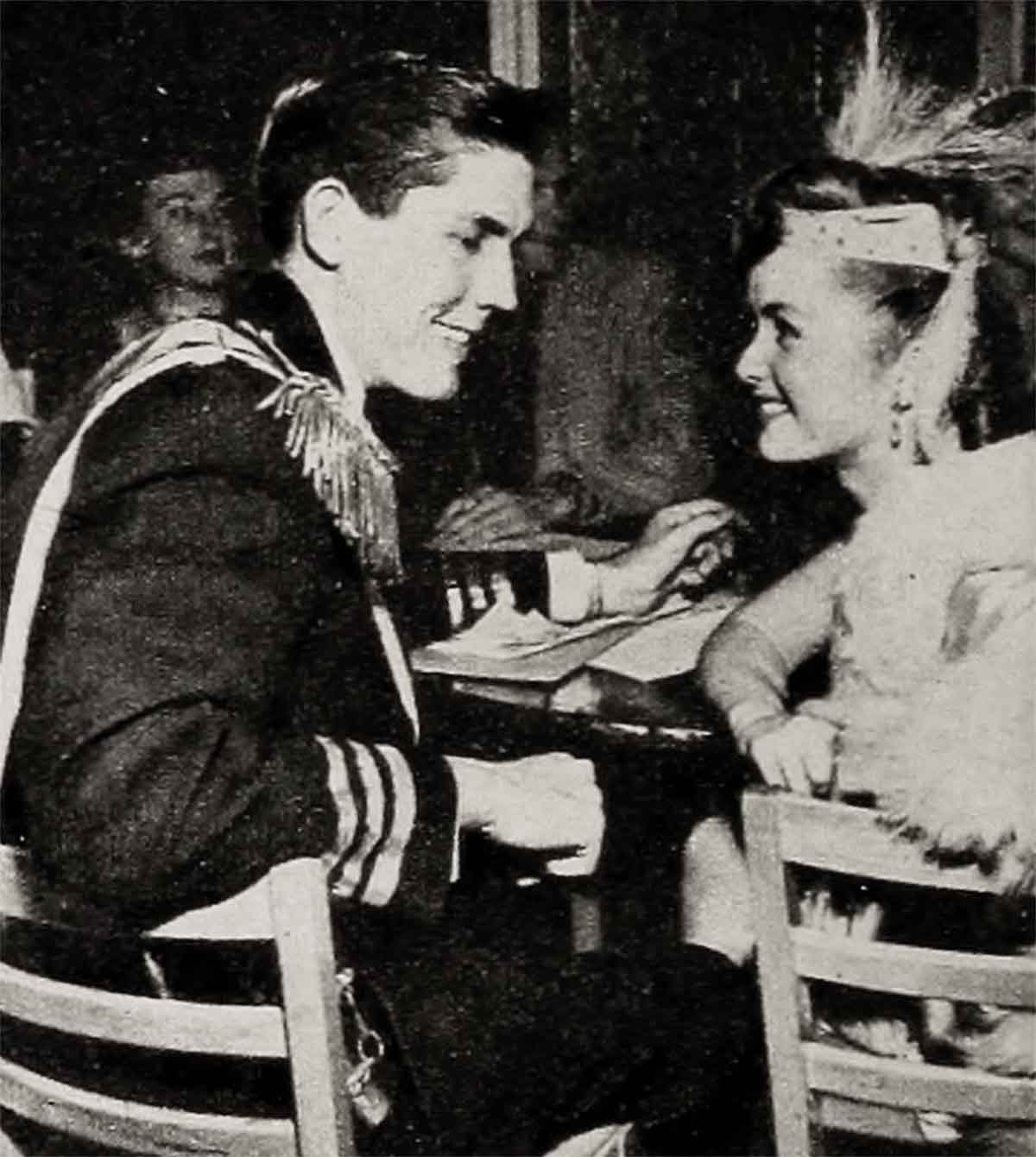

The food appears and Debbie takes one bite. “Know what I’m going to do? I’m going to ask Harriet Parsons if I can borrow Susan Slept Here to run for Mr. Schary on the lot. That’s the only way. If a thing’s important to you, do it yourself. He’s a very busy man, and why should he take time out to go see a picture I made for another company? But I want him to see it, because that’s the kind of picture I want to concentrate on. Comedy. Well, yes, singing and dancing, too, but musical comedy. Not just ingénues. I hate playing ingénues.

“When Red Skelton was on the lot, we used to talk about a picture we wanted to make together. About clowns. A father-and-daughter clown act—with a plot, too, of course. Very sad plot. But I’d love to play a part like that.

“Know the kind of comedy Lucille Ball does? The cream pie-in-the-face routine? Crazy! The living end! Love it. Have I ever had a pie in the face?” she winks broadly. “Had to practice, you know. Dick Powell calls me his clown in baggy britches. He’s a great man. People ask me who is the greatest talent in Hollywood, I say ‘Dick Powell.’ I love him. He’s just like a big, woolly bear.

“You know how busy he is? He’s only producing, directing and acting; he’s only making a couple of million a year to say nothing of his interests outside the industry. And he takes time to call me on the phone. Just calls and says, ‘Whatcha doing?’ I tell him whatever it is, and then he says, ‘Well, don’t let them work you too hard, Deb. Don’t do too much. You have to take some time out for rest and relaxation.’ Imagine! He’s the greatest. And June and those two kids—it’s a perfect marriage, a perfect family. He’s given her such a feeling of security. That’s what I need, what I’ll have to have in my marriage.

“Of course, I’m much more fortunate than most. Because of the closeness of my family, I’ve had emotional security all my life. I’ve grown up with it. And if I didn’t find it in my marriage, I’d be more lost than the person who had never had it. See what I mean? By the way, aren’t we going to talk about my love life today? Too bad. I had such a scoop for you, too!

“No, I was only kidding. No romance of mine would ever be of the ‘scoop’ variety. You know, when I’m not working, I go out a lot. I really enjoy it; it gives me a chance to be with boys I like and I love to dance. But it isn’t everything. Sometimes I don’t go out at all. I remember once, last year or the year before, when I didn’t have a date for eight months. I was taking lessons every night, voice, singing, dancing, and when you work that hard, you either don’t have time or you’re too tired for dating. I’ve been goofing off for about six months now, having a ball, and I’m glad to be back at work. I have plenty to do.

“I remember once when I didn’t have a date for eight months. I was too busy and too tired to go out. It didn’t bother me.”

“My next big project is a nightclub routine. I have very definite ideas about that. I think you really have to knock yourself out, give them everything you’ve got, stay out there almost but not quite as long as the audience wants you. Don’t overstay your welcome, but don’t let them go away feeling a little cheated. I spent the weekend in Las Vegas with Bob Neal and his mother, and we went to Danny Thomas’ opening. What a talent! The living end—the greatest. I want to be able to hold an audience like he does.

“People have the idea that you can whip a show together in six weeks or something. That’s crazy. It takes years to put a really good show together, and mine has to be sensational right from the beginning. I’d hate to be just a movie actress coming out to sing them a couple of dumb little songs. I want to knock ’em dead, lay ’em in the aisles.

“Maybe I’ll do an act alone or maybe with a couple of boys. I haven’t decided yet. I’m going to try to talk Roger Edens into writing some special material for me, an opening number. He wrote a song for me that’s the living end. People ask me who’s the greatest talent in Hollywood, I say ‘Roger Edens.’ Absolutely the greatest.

“My biggest problem is finding hit songs from old shows. My education has been badly neglected in that department. As far as I was concerned, New York was eight thousand miles away, and since Broadway didn’t have anything to do with movies, it was nowhere. So I really need a lot of filling in on show tunes.”

A friend offered her a file of same, and Debbie said instantly, “I’ll take it—and I’ll cherish it, too, because I know how people feel about their hobbies. You know, once I loaned my monkey collection to a hobby exhibit. I had monkeys from everywhere in the world that I’ve been and some that friends brought me and fans sent me. I loved every one of them. Well, these people promised to take good care of them, but while they were on exhibit two of my monkeys were stolen. What could they do to make up for that? They gave me first prize. I said, ‘Thanks a lot,’ and pinned the ribbon on one of my monkeys—but I don’t lend them out any more. That’s why I say I understand how much a person’s hobby means, and I’ll take good care of your song collection if you’ll trust me with it.

“Sure, I still collect monkeys. People still send me live ones, too, but mother sends them right back. She says, ‘We have the parakeets and Tour Jeté (the dog) and you in the house. That’s enough!’ See how she classifies me with the rest of the animals? We had a eat, too, Michael O’Flaherty Reynolds, but we had to give him up. He was too mean, the living end! He used to hide under the furniture or behind the door, and every time Mother went by he’d run out and grab her by the leg or bite her. He used to let me hold him for about seven seconds when he felt like it, because he knew that I was supposed to be his mistress. After that—look out!”

She talks on and on and, after a time, one can see that this talk has a pattern, an unconscious purpose. You should be amused. Debbie grins, frowns, leers, mugs; every thought wears a different expression of drollery. Her hands are never still, her hair literally stands on end, and her pleasure is evident when you are amused. Debbie is inwardly a clown. With or without the baggy britches, she’s always on stage, always knocking herself out for the reward of a smile.

Like great clowns before her, Debbie’s compulsion to keep us laughing hides a deep sensitivity that she doesn’t want exposed. She can be wounded—oh, yes, her heart isn’t scar-proof—but instinctively she knows that we gratefully accept her great talent for tickling us and dig no deeper into Debbie Reynolds. Let the world believe she’s a crazy, happy little kid who can belt a song, dance up a storm and make more faces than her monkeys, and the world lets the inner girl go her way in peace.

She’s a tiny one who doesn’t believe in her own talents half as much as you do. Because she became a star practically overnight, she isn’t ay all convinced that she’s deserving of a place so high and she works twice as hard to stay there. You’ll find her real feelings somewhere in the bright chatter that was calculated to make you smile. She shows her palms, covered with brutal blisters because she has worked out so strenuously on the bars for her role in Athena.

Debbie’s eyes may be on the stars, but her feet are planted pretty firmly on the ground. She has a curiously ancient wisdom, knowing without being old enough to have learned it that in the end we pay for everything we get. If not in the beginning, then in the end. She didn’t have to labor much to become Miss Burbank of 1948, and her subsequent movie contracts followed as a result of that contest—but how many girls who win contests of one kind or another actually become stars? Far from being a crazy kid, Debbie is a very bright little character who could read the handwriting on the wall more easily than most. Something was wrong. Getting into the movies had been too easy. Then she saw it. Because she had got in so easily, she was going to have to work like the dickens to prove her right to stay there. Hollywood was justifiably blasé about flash-in-the-pan contest winners.

Debbie was still pretty new at the acting game when she discovered that it isn’t all cakes and ale. She sat down all alone, there at the crossroads of her life, to decide which way it would go. If she had decided to take the road away from movies, she would have chucked the career without a backward glance, because that’s the way she is. She would have knocked herself out in the interest of other things, because she isn’t capable of half-hearted participation. Once she decided that a career in pictures was what she wanted, that it would be worth all the blood, sweat and tears, she began to give it a full measure of each.

It takes a full measure. Those blistered little hands will bleed before she willingly gives up working on the bar. Her practice clothes will be plastered to her back and her hair will be clinging damply to her forehead before she is satisfied with her dance routines. And there’ll be tears, too, though you will never see them, and it’s entirely possible that even her own family won’t know when her throat is aching and her eyes sting with salt.

Once there was a role in a picture that Debbie wanted in the worst way. Different from anything she had ever done, nonmusical, it would give her a chance to display whatever genuine acting ability she possessed. When she won the part, Deb was happy. Than this there is no happier. She glowed, she sparkled, she danced on the wind, she bubbled inwardly as she has always done on the surface. She had worked hard and now she was rewarded.

And then another actress took over the role when she thought beyond doubt that the coveted picture was hers.

Debbie didn’t throw a temperamental tantrum—she wouldn’t know how. But she couldn’t make the little clown come to life, either. The loss was too painful and it came too quickly, before she could throw those defenses up. That day, for the first and perhaps for the only time, Hollywood saw Debbie disarmed—without the shield of a wry grin and a comic answer.

In a quiet voice she agreed with the executives who broke the news to her that the more experienced actress would probably do a whale of a job. That was the gesture of a good sport. And then she added evenly, “I hope you’ll never again ask me to give up anything that means as much as this role meant to me.” These were the tears.

She isn’t bitter—never bitter—but the experience taught her something. So that she says now, “I’ve tested twice for Oklahoma. I’d really love to play that role, to do Ado Annie, but from the beginning I’ve somehow known inside myself that I wasn’t going to get it. So, I’ll keep doing tests as long as they ask me, but when they cast somebody else, I’m not going to be disappointed. I pas know.”

She isn’t going to hope again in that particular way. She hoped too hard once and got hurt, and she’s too smart a girl to need two belts over the head where one will suffice. Nobody knows whether Debbie ever took a belt over the heart because she isn’t saying.

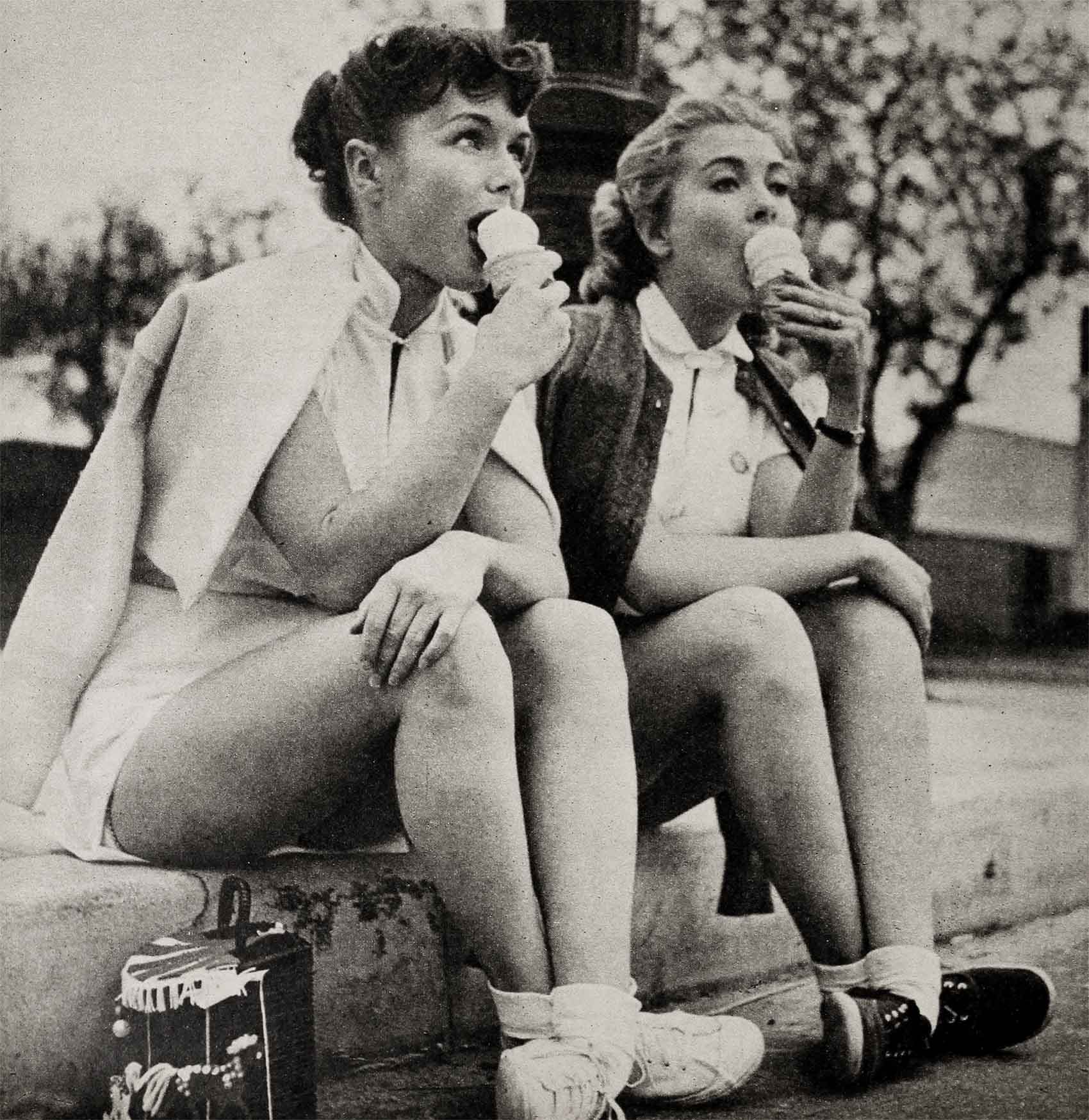

She continues to confound—and even irritate—the biographers of Hollywood by refusing to follow the patterns of behavior they expect. By this time success certainly should have gone to her little round head. Instead of which she does pretty much what she has always done.

She doesn’t spend money like a drunken sailor, nor buy and wreck Cadillacs, nor make headlines by her contractual disagreements with MGM. She refuses to elope and divorce or even engage and disengage. The girl is twenty-two years old, for heaven’s sake, and she still doesn’t drink or smoke!

The columnists and feature writers have cooed about how refreshing it was to have this natural little person in our midst in tones so sugary that it took a steady hand to read the stories after a while. Nothing happened, except that Debbie went on working and improving as an actress, doing outside the studio the things she had always done.

Then they took the opposite tack, When, they asked sourly, was this girl going to grow up? Wasn’t she a little old to be climbing trees? If Debbie was stung by their ridicule of her Girl Scout activities, of the fact that she played the French horn, she gave no indication. The grin stayed on straight, her talents continued to blossom and she went her own way.

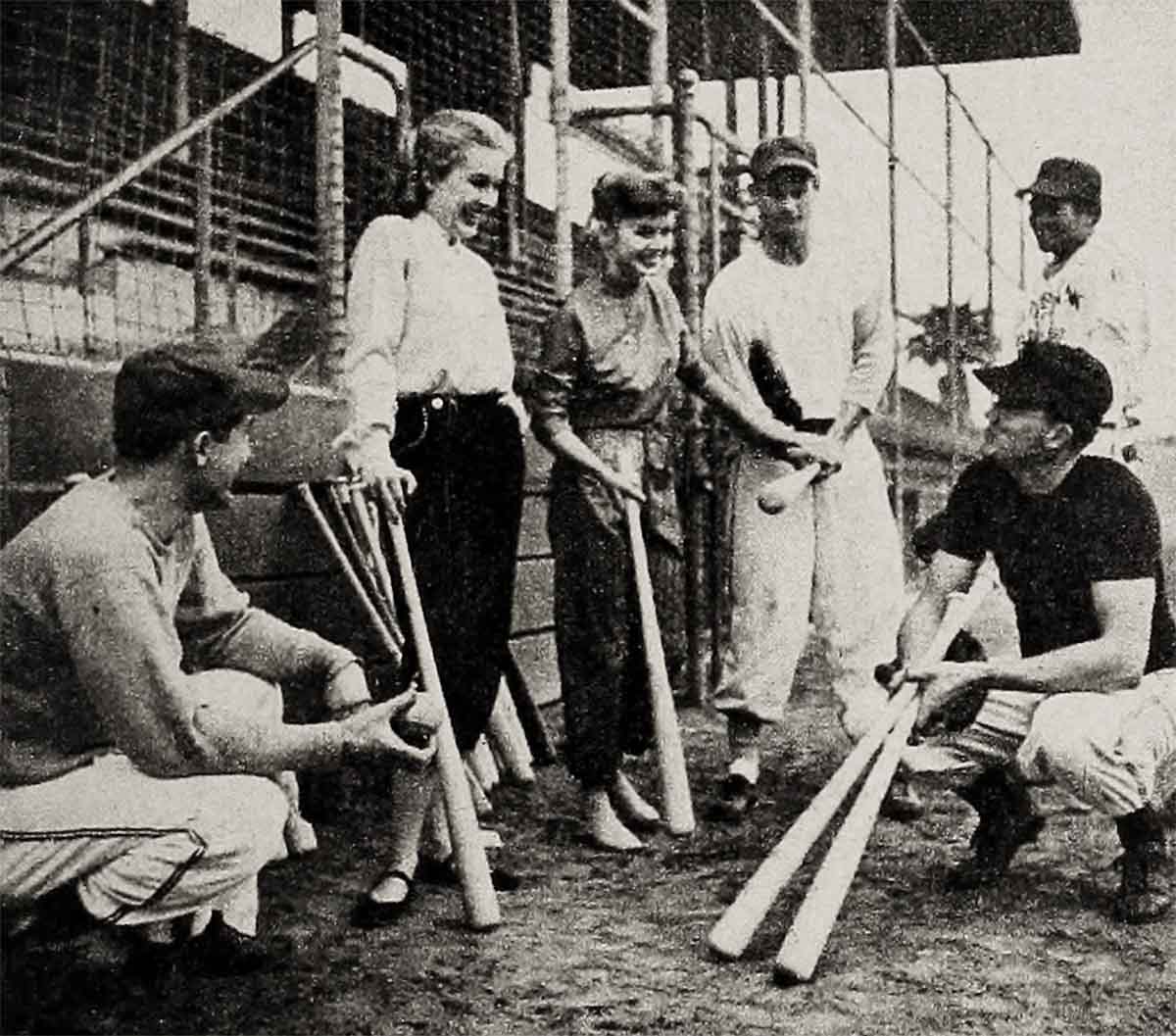

The final blow to the scoffers has been the steadfast loyalty of the boys Debbie dates. They, too, have been ridiculed—for robbing the cradle, for enjoying the company of a girl who considers a weinie roast as much fun as a premiére, for having their romantic appeal passed over by a girl who says, “I can take a good night kiss or leave it alone.” According to their standards, little Miss Reynolds ought to be a one-date girl, but the most eligible bachelors in town keep coming back. She can have her choice of dates any night of the week and if it happens to be one of the periods when she’s working or studying, they’ll try again in three months or six. It seems strange, to say the least, in a town where eligible young males are at a premium, but that’s the way the ball bounces. Debbie’s ball, anyhow.

Maybe she’s too busy forging a career to think of romance, as she says. And maybe she got clobbered once, as she isn’t saying. Anyway, Debbie Reynolds isn’t going to have one of those early, scalded-over-with-scandal marriages spawned by the dizzy pace of kids who don’t know enough to come in out of the glamour.

It isn’t that she’s rebellious in not doing the tragic expected; it’s just that she wouldn’t be Debbie if she did.

THE END

—BY TONI NOEL

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954