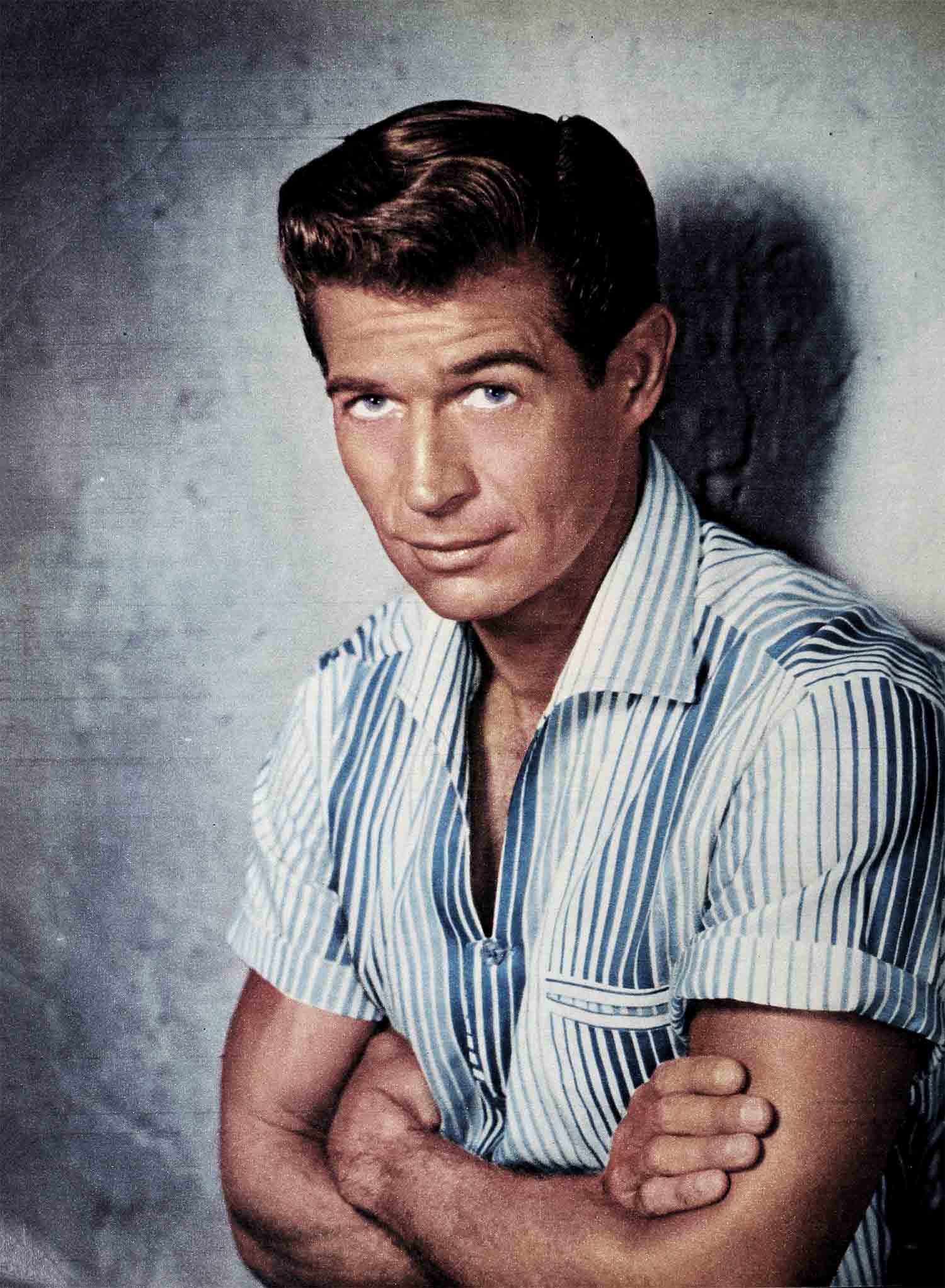

George Nader And The Marriage Question

Even if I hadn’t recognized his voice, I would have known George Nader was on the other end of the line. “Are you free next Saturday night, Barbara?”

“I am.”

“I have tickets for ‘Tea and Sympathy.’ It starts at eight-thirty, which means we’ll have to leave your house by six-thirty-five. That allows us one hour for dinner.”

“Sounds fine, George.”

“It’s formal. Goodbye, Barbara.”

“ ’Bye, George.”

My mother, who had been busy setting the table, also knew who it was, by my replies. “That must have been George Nader, dear.”

She was so right! The phone call was typical of him. Not exactly businesslike, but short and precise, without the chit-chat that ordinarily goes with a phone call. or any type of conversation. George knows what he wants and what’s more, when you’re with him, you always know where you stand. I like that.

In this respect, George has never changed, though he has in other ways since I first met him, back in 1950.

Fresh from Santa Barbara, I was standing in the registration line of the Pasadena Playhouse when a handsome young man tapped me on the shoulder. “Is your name Barbara?”

I thought he was just trying to strike up an acquaintance. “Yes,” I said coolly, “but I’m busy right now.”

He was persistent. “I’m George. How about a cup of coffee after class? Maybe I can help you out in some way.”

Now there’s a novel approach, I thought. But my conclusions had been quite wrong.

“I guess I should explain. I’m related to the Kublys, with whom you’re staying. They asked me to—”

“George Nader!” I burst out. “Now I know. They told me about you. I’m so sorry.”

I really wasn’t—not after I noticed the envious glances I received from almost every other female on the campus!

From the very beginning, George took a sort of big-brother interest in me. He made sure that I registered properly, gave me advice on classes and instructors, and met me for coffee fairly regularly, “to talk things over.”

But we didn’t date in those days. With both of us, concentration on our work came first. And besides, I didn’t have the time to go out. To help pay my way, I baby-sat most nights, and during the day—in addition to classes—I worked in the Playhouse office as a switchboard operator, typist, and general Girl Friday.

After George left the Playhouse, two years before I did, I didn’t see him again till both of us had been signed to longterm contracts by Universal-International.

I’ll never forget the day I was having lunch at the commissary, and again someone tapped me firmly on the shoulder. “If you need any help with your registration, Miss . . .”

Thinking it was a studio representative who helps employees get their new automobile license plates, I shook my head. “No, thanks, not this year. I already have—” By then I had turned around and faced him. “George Nader!” This outcry was becoming a habit.

Now, everyone at the commissary knew we were old friends. I also had the feeling that quite a few of the girls were wishing they could have been in my place—just as they did at the Pasadena Playhouse.

Since that time, George and I have seen each other a lot—and not just over a cup of coffee, as during the first year of our acquaintance.

I soon began to notice that, while in many respects he is still the same old George, in other ways he has changed considerably. Take, for example, his attitude toward his work.

George is just as ambitious as ever, but today he possesses an ability for which every actor strives, and very, very few ever succeed. No matter how hard George works, how involved he gets in a scene, or whatever problems confront him during the day, he can forget all about them the moment he leaves the studio.

Recently, at the studio, I watched him in a scene from “Away All Boats,” in which he has one of the leads. For over four hours I saw him dive beneath the water, coming up for air only when he could stay under no longer. It was one of the most grueling scenes I’d ever watched.

Remembering that we had a dinner date that night, before I left I suggested we postpone it to another day.

“Oh, no,” George protested. “I have tickets for the theatre.”

“But you’ll be too tired!”

“I’ll be all right,” he promised.

When we had dinner before the show, I did notice that his usual bearlike appetite had disappeared, obviously from exhaustion. But after three cups of coffee, he perked up again and was an enjoyable escort for the rest of the evening. And not once, during all this time, did he mention how hard he had worked that day. To him, this was just part of his job.

Contrary to what might be expected, George and I seldom talk about our careers. Maybe that’s why we get along so well. We don’t try to tell each other what to do, or what not to do. We don’t criticize each other, at least not in a negative way. At the same time, we are one hundred percent serious in our efforts to get ahead.

Talking for George—and I believe this holds true for myself as well—I’d like to stress that his ambition is not of the “I don’t care whose feet I step on to get ahead” variety. His is a much more adult, businesslike approach which has only one drawback: He tries to do too much himself, doesn’t delegate enough of his obligations to someone else.

For instance, take his attitude about his fans.

George has regular meetings with the local presidents of his fan clubs, which, I agree, is a fine idea. But till recently, he also answered every one of his fan letters personally, by hand. With the volume of mail George receives, this is indeed a time-consuming job.

Only recently did he change to a system used by many stars, in that they read their letters, and answer them personally, but not in their own handwriting. Instead, they dictate their replies to a secretary, thus saving themselves many valuable hours each week. Reluctantly, George finally switched to this, but only after it became physically impossible for him to answer all his correspondence by hand.

One of George’s greatest assets is his self-assurance and preciseness. These are obvious not only in his phone calls but in every phase of his life.

George is the only man I have ever dated who has never asked me where I wanted to eat, or what I wanted to do. He makes the selections, figuring no doubt that if I objected, I’d let him know!

He is just as specific about ordering a meal. Once we had dinner at a little Viennese restaurant on Sunset Boulevard. When the waiter brought us the menu, I got lost in a maze of Sauerbraten, Schnitzel, Klopse and Bratwurste. Finally, I looked at George helplessly, and he wasn’t even studying the menu!

“Do you have any suggestions?” I asked.

“I do. Would you like me to order for you?”

“I’d love that.”

When the waiter came for our orders, George rattled off a bunch of German dishes that made my head spin. And apparently he named them with perfect pronunciation, because when he finished, the waiter said to him in amazement, “Sie sprechen Deutsch, nicht wahr?”

“I beg your pardon?” asked George.

“I said you speak German, don’t you?

“I’m afraid not,” George laughed. “Before we came here I checked with a friend of mine who was born in Germany. He suggested what to order and taught me how to pronounce the dishes.”

Typically George, once again. He’d thought out the whole evening from Wiener Schnitzel to Apple Strudel.

I hope that, after what I’ve said about George so far, no one draws the conclusion that he’s too serious to have a sense of humor. While he’s by no means the giggling, laugh-at-every-joke type of character, he has a healthy appreciation for a good joke, and can dish it out as well as take it.

Once he took me to a Christmas party, where the hostess asked for four volunteers for a game—which she wouldn’t describe till after she had secured them. George happily raised his hand—then found himself being blindfolded, and told that his partner, a girl who was also blindfolded, would feed him cereal with a spoon. They were to try to beat the other couple in this speed contest.

George and his partner won, but by the time they had finished, he had cereal in his hair, all over his face, suit, even on his socks. I’ve never seen him laugh so hard.

As I said before, George can turn the tables, too.

One day I again visited the set of “Away All Boats.” In one scene, Jeff Chandler is supposed to man an anti-aircraft gun, aim at the sky (inside the studio) in search for enemy planes, and fire.

I knew something was up when I noticed George walk over to the propman, Bobby Murdock, and whisper in his ear.

When the director called the cast for the final rehearsal, George was eager, much too eager for the scene. Everything went according to the script, until Jeff aimed the gun into the sky, and started firing. All of a sudden—plop, plop, plop—three birds fell down from the ceiling, almost on Jeff’s helmeted head! On instructions from George, Bobby Murdock had rigged them up so they’d come down the moment Jeff started firing. The whole cast and crew went into hysterics.

But I played an even worse trick on George.

In spite of his control, I knew that at times George can lose his temper, and I was just the girl to achieve this.

Actually, this was not what I had in mind the night it happened, when he was driving me home from a party.

Both of us have a tendency to be a little on the dogmatic side. That’s what caused the ruckus when he claimed, “You are one of the few girls I know who is never uncertain about anything. You know exactly what you want out of life.”

“George!” I protested unhappily. “You make me sound like a calculating machine. You know that isn’t so.” And as an afterthought, “I think you are the one who is calculating.”

He winced a bit at that reply, and I knew instantly that this was my opportunity to heckle him. And what a game I made of it! I kept needling him about it all the way home, till I feared if I went any further, he’d tell me to walk the rest of the way. Just at the point where he really started to lose his temper, I began to laugh, and then he laughed, too.

I don’t think George and I would get into these predicaments, if we weren’t so very much alike in our outlooks on life. What we believe in we are ready to argue about to the last breath.

George and I are alike in another way, too. From time to time we have to get away from people, be completely by ourselves in order to regain the perspective and peace of mind which is so easy to lose In a profession as hectic as ours.

When I get into one of these moods, I usually throw a couple of suitcases into my car and take off for La Jolla.

George told me he finds more solitude in the mountains. When he finishes a picture, he usually drives up to Lake Arrowhead or Big Bear, or if he has enough time, into the High Sierras, where he rents a cabin, cooks his own meals, sees no one for at least two days—or longer, if he can stay away. By the time he gets back, he is relaxed and at ease.

Undoubtedly, this has helped him to stay as level-headed as he is. With his success in films, and the fact that he is one of the most sought-after, most eligible bachelors in town, it would have been easy for him to become conceited. George isn’t. On the contrary, he makes a very special effort to be a nice person.

Take, for instance, the day he found out that one of the crew members on “Lady Godiva” had a birthday. No one knew about it till five o’clock, when the fellow let it slip out. By then everyone thought it was too late to do anything about it—everyone but George.

He sneaked away from the set, rushed home, picked up a set of glasses and dishes, stopped at a bakery on the way back for a huge cake and at a liquor store for a couple of bottles of champagne, and by five-forty-five, had arranged a birthday party right on the set. It’s this awareness of people and situations that makes him so well liked. It would also make him a good husband.

Although he is thirty-four and has had his share of romance, George doesn’t talk much about women, except the ones who have made a tremendous impression on him—and not in a romantic way.

One of these is Joan Crawford, whom he first met when he was still an unknown in Hollywood. She had seen George on a television show and wanted him to appear in a TV pilot film she was planning to make. But, as George says, “I couldn’t have been more flattered—and it couldn’t have happened at a more inopportune time!” For then he was making a picture called “Miss Robin Crusoe,” for which he had to maintain a week’s growth of beard. When, in the elegant MCA offices in Beverly Hills, George met Miss Crawford for the first time, “She looked like a dream,” he told me, “wearing all-black, pearls and sables—and I looked like a bum!”

Because he was still tied up with “Miss Robin Crusoe,” George had to turn down Miss Crawford’s offer. And then, when she was preparing to make her second pilot film, she sent for George again. But this time, he couldn’t do it because he was signed to do six pictures for Loretta Young’s TV company. “But,” says George, “Joan still put in a great plug for me with U-I. They tested me eventually, and signed me. That was the turning point in my career.”

Another lady George will never forget is Helen Hayes, whom he first met at a dinner given by Joan Crawford. When he found himself sitting elbow to elbow with the great Miss Hayes, George says, “I really felt like a trespasser. But she was so gracious and natural, she put me at ease immediately. When we discussed acting,” he recalls, “I told her I envied people like herself who weren’t nervous when they performed. She gave me an amused look and said to me, ‘When you stop being nervous, you don’t try as hard—and then you’re really in trouble!’ When,” George has said, “Miss Hayes admitted she still shook before every performance, I decided there was hope for me!”

Although George and I have seldom discussed marriage in general, I know that he wants to wait until he is financially more secure. He once said, “I want to be ready for marriage when the time comes. It’s an important responsibility, and if you really love a girl, you want to give her the best. To do this, you first have to be in a position to afford the best.” So, being realistic about it all, he’s been concentrating on getting his career well-organized. But even if he fell in love with a girl tomorrow, George just isn’t the type who would do anything head over heels. In marriage, as in everything else in life, George knows what he wants—including the proper time to do it.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1956