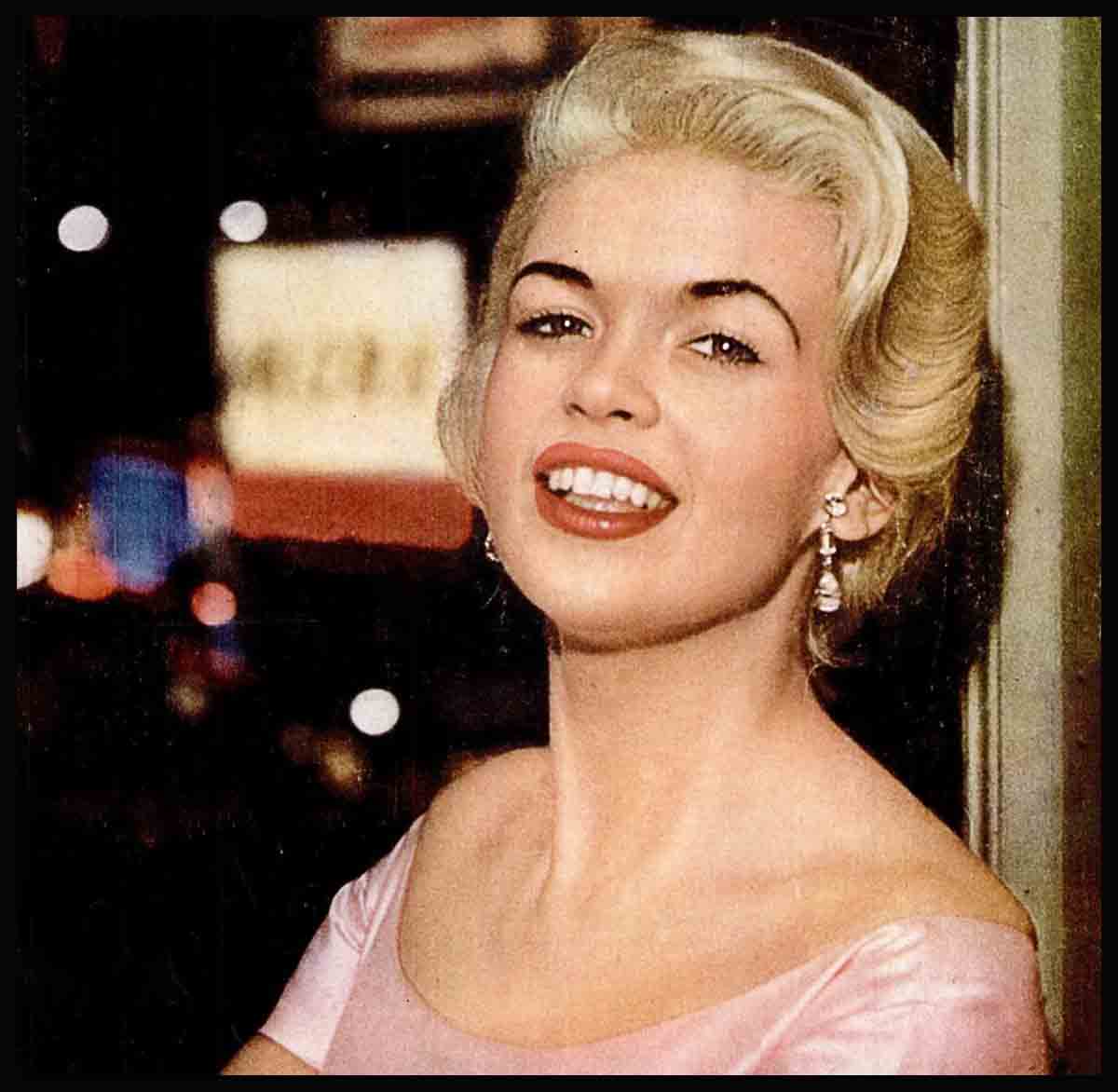

Star’s Legend In The Making—Jayne Mansfield

Though the thought has never er her pretty blond head, Jayne Mansfield is one of the most interesting sociological studies to be found anywhere in the U.S. this spring. Miss Mansfield has burst dazzlingly upon the theatrical world a tar of a Broadway comedy called Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? and currently seems to be getting her name and photograph into more Broadway columns and movie magazines than any other actress alive. A number of Hollywood studios are bidding for her services and there seems to be a very good chance that she will someday become a full-fledged movie queen. Yet at the moment Miss Mansfield is only in what might be called the larval stage. Her face has not yet been metamorphosed by Hollywood’s make-up and lighting experts, nor has her mind by exposure to the Actors’ Studio, poetry and imaginative movie producers. Miss Mansfield is still just herself, friendly and frank, perhaps even somewhat naive in her own calculating way. This is a rare situation, for ordinarily a movie queen is presented to the public only after some studio has gone to immense expense changing her over completely, to the point where her own mother would not recognize her.

Miss Mansfield does not even obey cliché No. 1 of the movie queen, which is to act bored with success. No teen-ager ever exhibited so much tenacity at seeking autographs as she does at signing them; she will stand in wind, rain or snow until her last admirer is satisfied. She still preserves her first fan letter which came, when she was a Hollywood starlet, from a California schoolboy named Mendoza, and she reads every newspaper to see whether such columnists as Walter Winchell and Earl Wilson have said anything about her. (If they have nothing for several days she gets on the phone.) While having some pictures taken recently she told the photographer apropos of nothing, “Do you know what Winchell once said about me? He said Jayne Mansfield ‘is as beautiful as Marilyn Monroe in every department and effortlessly delivers the most devastating impression in years.’ I’ve got it memorized. By the way, what does devastating mean?”

Many others besdes Winchell have compared Miss Mansfield to Marilyn Monroe. This is perhaps inevitable, for in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? she is cast as a rollicking caricature of a dumb blond movie queen. Moreover she just naturally has the same come-hither-you-brute sort of voice and look as Miss Monroe. But the comparison, which a more seasoned actress would at least pretend to love, does not seem to please Miss Mansfield at all, “Marilyn is very attractive and all that,” she has said, “but she and I are entirely different. I can dye my hair and play a serious part.” For that matter Miss Mansfield would not even have to dye her hair. She could just let it grow back to its natural color, which she admits, again in gross violation of the movie queen’s code, is brown.

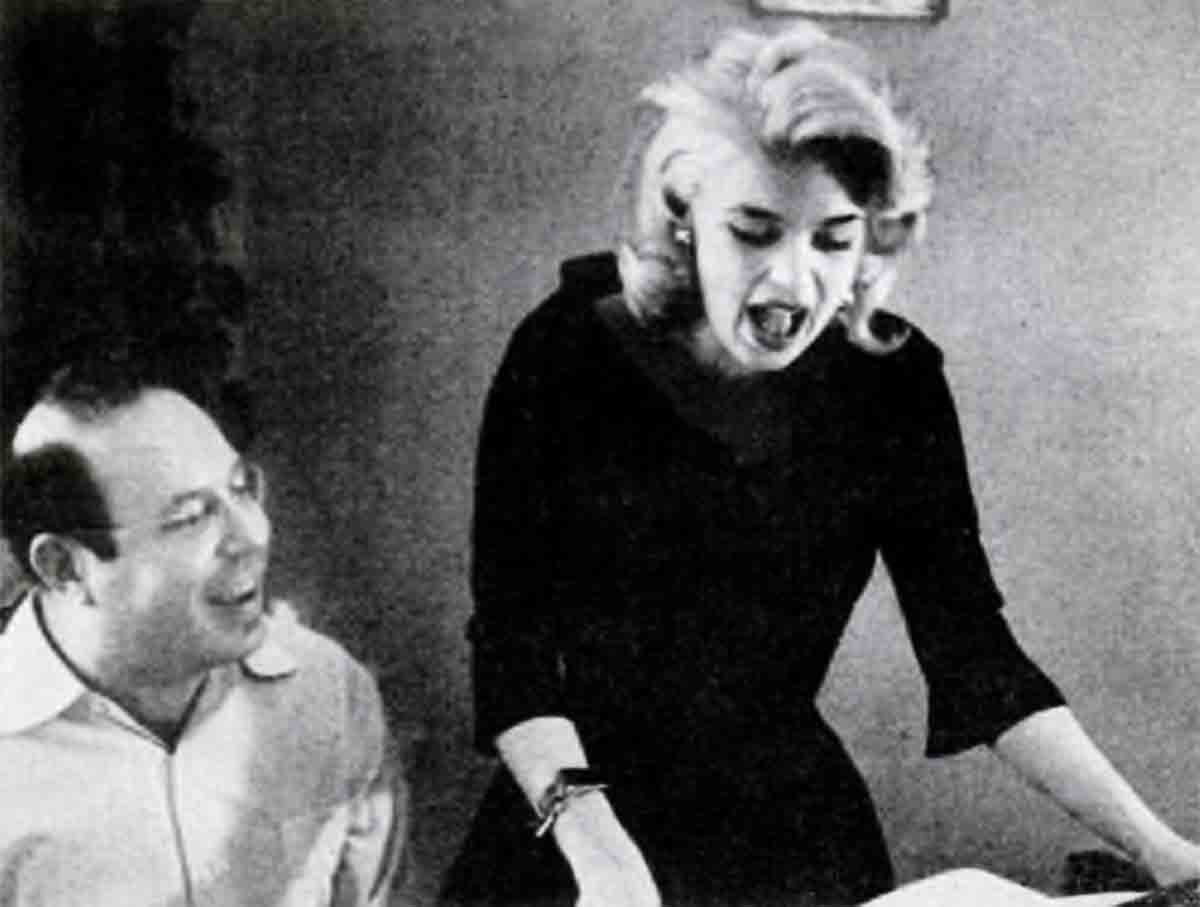

Although to date Miss Mansfield has appeared in only five movies, mostly in the kind of bit parts which Hollywood calls suitable for any “big blonde,” and in a play in which a good many critics feel she is only being her own exuberant self, her confidence in her acting ability seems boundless. Recently she made a screen test for a 20th Century-Fox filming of the novel The Wayward Bus. This was a critical event in her brief career, with a starring role at $1,500 a week—or more—as the immediate prize. She was tutored for it by George Axelrod, the author and director of Rock Hunter, who wanted her to do something simple, light and airy before the cameras. Miss Mansfield, however, was all for trying some excerpts from the highly overwrought role of Blanche DuBois in the deadly serious A Streetcar Named Desire.

When Axelrod expressed amazement, Miss Mansfield said airily, “Oh, that’s because you’ve never seen me with my hair back. I can look very Italian and Russian and all that.” Axelrod had her run through a few Blanche DuBois lines, then gently dissuaded her. “Unless people are prepared for what’s coming,” he told her, “they might figure you’re imitating Judy Holliday imitating Marilyn Monroe trying to play Blanche.”

At times Miss Mansfield claims that her real ambition is to play the lead in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. This is a pretty impressive statement, for the listener, looking at that halo of chromium hair, is usually surprised that Miss Mansfield ever even heard of The Magic Mountain. However, one unchivalrous reporter slyly asked Miss Mansfield the name of the author. There was a long and agonized pause until someone in the room mercifully changed the subject. Miss Mansfield frequently gets into this sort of trouble by overstepping herself. Recently she was telling an interviewer how domestic she was. In all innocence he as

“Do you like cooking?” Again there was a pause, then she replied plaid shirt and cook up some bacon and eggs. I can also cook turkeys. They’re so good when they’re cooked, you know.”

Part of Miss MansfieId’s sublime faith in her own histrionics stems from a man named David Sturgis, an elderly astrologer whom she regards as the most erudite person she has ever met. Some of Sturgis’ conversation rather baffles her, as for example when he recently told her that the stars would make her more feminine after the of 30. Miss Mansfield, who is keenly aware that her most publicized feature is a figure measuring 40-21-35½ has a characteristic gesture in which she sighs, throws back her shoulders and surreptitiously glances down to note the effect. She did so at this point and asked, “You mean that now I look masculine?”

But most of what Sturgis says is music to Miss Mansfield’s ears. Her horoscope, he has reported, shows that under her ruling sign of Aries she is destined to outshine not only Marilyn Monroe, born under the less dramatic sign of Gemini, but Gina Lollobrigida and Sophia Loren as well. She will be very big in England, Japan, France, Italy and of all places Calcutta, which had not occurred even to her as a possible scene of triumph. He also told her recently, after consulting the stars once more, that her period of utmost greatness will be from June 9 of this year to June 11, 1962. “That figures,” she said solemnly.

As Sturgis interprets the zodiac, Miss Mansfield’s career should be guided by a Leo. By the merest coincidence Sturgis is himself a Leo and has an unproduced play in his trunk called The Loon. Miss Mansfield took a look at it recently and promptly sent word to her agent Bill Shiffrin, out in Hollywood, that she was determined to stay in New York and appear in it. Shiffrin got to New York as fast as he could, read the play and claimed it would set Miss Mansfield’s career back at least several decades. Miss Mansfield disagrees. As she describes it, “There’s a bird upstairs and a couple of half-wits running around and a man with dirt under his fingernails. It’s very mysterious; I loved what I read of it.” Any day now she plans to read the rest.

She is very unhappy that Bill Shiffrin does not see eye to eye with her on the matter of astrology. “I keep telling Bill that Mr. Sturgis used to advise Duse and Nijinsky and all kinds of people like that,” she complained to an acquaintance recently, “but Bill just says, ‘All dead people.’ Well, I’ll admit that Nijinsky came to a bad end, but he was very big while he had it. Bill thinks I’m gullible, but I’m really not. I only like this astrology thing because there’s a lot of truth to it.”

The movie queen is supposed to pretend that she was “discovered,” rather against her own blasé wishes. Miss Mansfield readily concedes that she has dreamed of practically nothing else but stardom ever since about the age of 6 and that she had a terrible time persuading Hollywood to see things her way. In fact she had trouble persuading a number of people in various places.

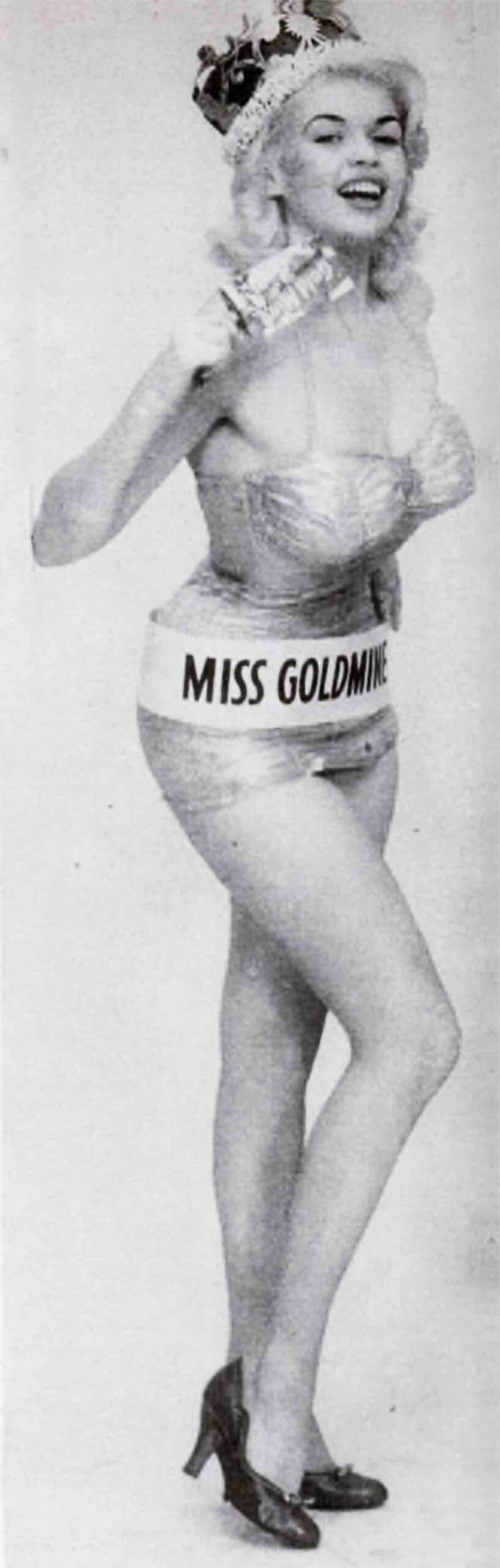

Her mother and her stepfather, who is a sales engineer in Dallas, were never quite in sympathy with her teen-age plans to storm the bastions of Hollywood so she got married when she was 16 and still in high school. Her husband, it developed, also thought that her ambitions were just a teen-age obsession. They had a baby girl, who is now 5, and went to college together at the University of Texas. As one of the young couples who have become so common on campuses nowadays, they staggered their schedules so that one could wheel the baby carriage up to a classroom as the other exited. Meanwhile Miss Mansfield, a high B student even in such subjects as mathematics, posed for a women’s art class. modeled dresses and coats and entered every beauty contest in sight, partly to help make ends meet but mostly in hope of catching Hollywood’s eye.

In the spring of 1954, after her husband had finished college and his draft stint. Miss Mansfield finally persuaded him to take her to Hollywood. About all she had to recommend her were a few bit parts with university and little theater groups in Texas and some bathing suit queenships such as Miss Photoflash of 1952. But she had no hesitation whatever in simply calling the Paramount studio and asking for a screen test. A girl in the casting department, bowled over by this effrontery, said. “All right, we’ll give you a test; you sound unusual.” Although she flunked it, partly through camera fright. this did not reduce her self-confidence or drive in the slightest. If she could not at once get into the movies, at least she could get into the papers and keep knocking at the doors.

Providential hoax

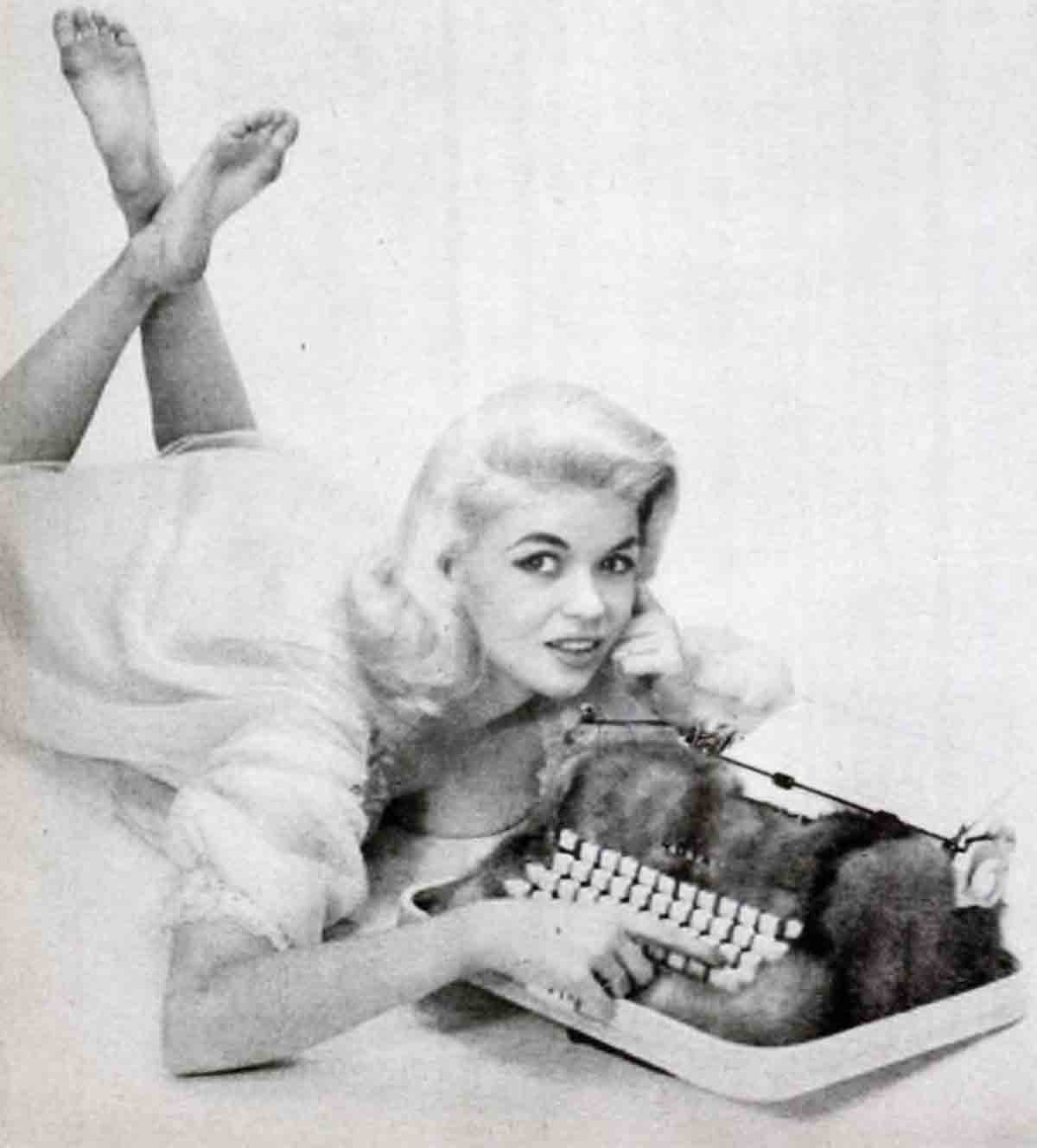

For all her indefatigable ambition, Miss Mansfield might still be just an anonymous starlet had it not been for one of the strangest happenstances that ever took place even in Hollywood. One of the pin-up pictures with which she and her press agent flooded the town happened to catch the eye of Charles Lederer, a writer, director and famed practical joker. Lederer promptly sat down and wrote, over a forged signature of Miss Mansfield’s, a long letter to his friend Jack Goodman, of the publishing house of Simon and Schuster Inc.: “Now, Mr. Goodman, I suppose everyone says they have a novel in them, but I know I have! In fact I have already written seven chapters. . . . My novel is called ‘Celluloide.’ concerns a young actress (me, I guess) and an assistant director of a slightly more mature age. . . . I can’t send you the manuscript even if you want it because I only have one copy and besides I don’t think you could read it in its present form. None of the names I made up for the characters sounded real to me so I left them blank until I could think of some good ones. Do your other writers have the same sort of difficulty in that direction?” And so on in this vein for several pages which went off to Goodman with the photograph. Goodman figured the letter was a rib, but on the other hand anything can happen in Hollywood and an author with a figure like Miss Mansfield’s is nothing for a publisher to brush lightly aside.

Thus there began a lively correspondence between Lederer and Goodman in the course of which Lederer even wrote a short story purporting to come from Miss Mansfield’s typewriter, and Goodman dictated in reply some letters which were masterpieces of the dead-pan noncommittal. Miss Mansfield, of course, knew nothing of the exchange. It was one of Lederer’s proudest hoaxes and in the course of events he mentioned it to another friend of his, George Axelrod, at the same time showing the photograph which started the whole thing. Axelrod, who was casting Rock Hunter, took one look and cried, “That’s the girl we’ve been looking for!”

Up to that time Axelrod had been looking at girls who could act but did not at all look the part of the dumb blond movie queen to end all dumb blond movie queens, or at girls who looked the part but could not act. Miss Mansfield proved a happy compromise. On the physical side she surpassed all of Axelrod’s fondest hopes and she acted the role if not with finesse at least with abandon. At the tryout she was asked to do a love scene with Hero Orson Bean, who was jaded from many weary afternoons of trying the same scene with a procession of hopefuls. Bean conceded afterward, “When I came to, I asked for shies number of the truck.” Miss Mansfield was signed practically on the spot and Bean has since been hit by the same truck at eight performances a week.

To the Broadway veterans connected with the show, Miss Mansfield has been a unique and perhaps traumatic experience. Stage actors are brought up in the strict school of sticking as closely as possible to the same “business,” i.e., staging, use of props, etc. in every performance. This sort of regimentation is repugnant to Miss Mansfield, and the other players in Rock Hunter have had to steel themselves to be ready for anything. As Axelrod has said, “There is absolutely no chance, whether by design or by coincidence, that Jayne will ever do two shows alike.”

There is one scene where Orson Bean and another actor engage in a rough-and-tumble bit of judo in which they go flying rather precariously about the stage. It was originally intended that Miss Mansfield, who is on stage during this battle, should enter wearing a red stole. Upon removing it, she was to put it safely on the back of a chair, out of harm’s way. But in practice she never dropped it in the same place twice and Axelrod finally had to take it away. “Somebody would have tripped on it and been killed,” he explains.

During rehearsals Bean noticed that in every scene where Miss Mansfield was supposed to approach him she did not stride directly tow him but detoured in a slight are, placing herself in such a position as to make him turn his back on the audience to talk to her. This is the classical trick known as upstaging and is frowned upon in the theater. Bean mentioned this fact to her, where-upon Miss Mansfield said, vaguely but with every appearance of sincerity, “We’ll work it out.” He reported recently, “We’ve worked it out, all right. I’ve become reconciled to it.” Members of the cast have been asked to excuse such matters on the grounds of inexperience. But one of them once plaintively asked, “Why is it that her naiveté never leads her to downstageanybody?”

The other actors also know that Miss Mansfield greatly prefers movie magazines to Theatre Arts and they have a sneaking suspicion that she pow wishes that the show would close g6 that she could return to Hollywood, They are often miffed when, anding with her in the wings, concentrating on getting themselves into the spirit of their next entrance, they hear her practicing the speeches her press agent has written for her next day’s’ public appearances. Nonetheless they seem to have a genuine if somewhat guarded affection for her and by and large they take an indulgent view. For one thing, she represents money in the bank. All the drama critics have liked her performance and it seems likely that her skyrocket fame will keep the show going considerably longer than it otherwise might. Moreover she always does her best, a phenomenon which Axelrod shrewdly encourages by pretending from time to time that somebody like Sam Goldwyn or Darryl Zanuck is in the audience. This always lifts her to the absolute peak of her performance. “Of course if I just told her was there, nothing would happen,” Axelrod says. can’t give her a movie role.”

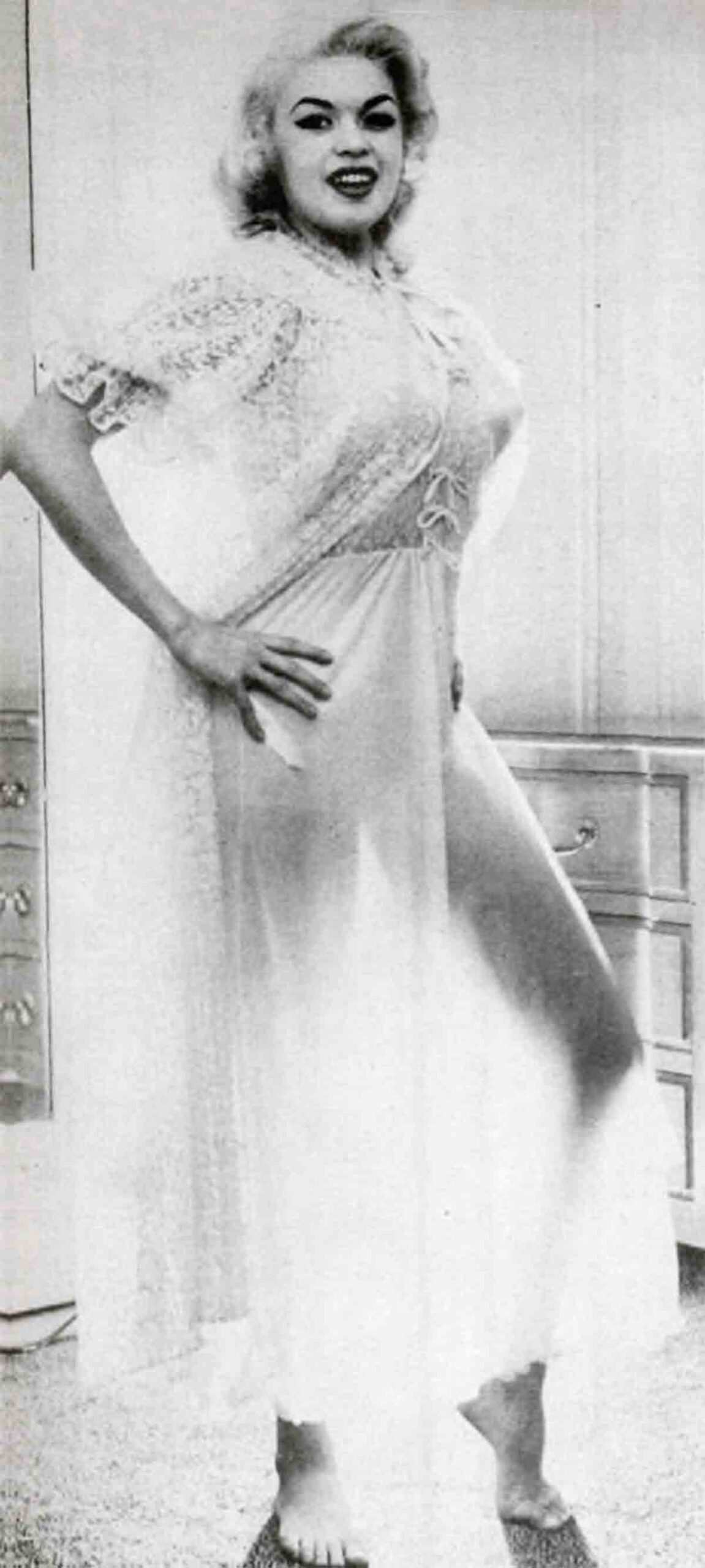

As might be expected, Miss Mansfield leads a rather helter-skelter life in New York. She no longer has her young husband. About a year ago he gave her the choice between the marriage and her career, and as a result he is now down in Texas editing a railroad magazine while she conquers Broadway. They are in the process of getting divorced, but this may take some time because her husband feels that the theater world is no place to bring up a child and is asking for custody. Miss Mansfield lives near the theater in a two-room apartment, as alone as a girl can possibly be in such cramped quarters with a daughter, a maid and two Chihuahuas. A visitor is likely to find her busy putting up her hair, which requires constant attention, while her daughter plays the television set and a record player, the maid vacuums the rugs, two phones ring constantly and the Chihuahuas, only one of which is housebroken, leap about. Miss Mansfield finds the apartment very restful. Until recently she lived in one room and had, in addition to her present menage, three cats and a 135-pound great Dane.

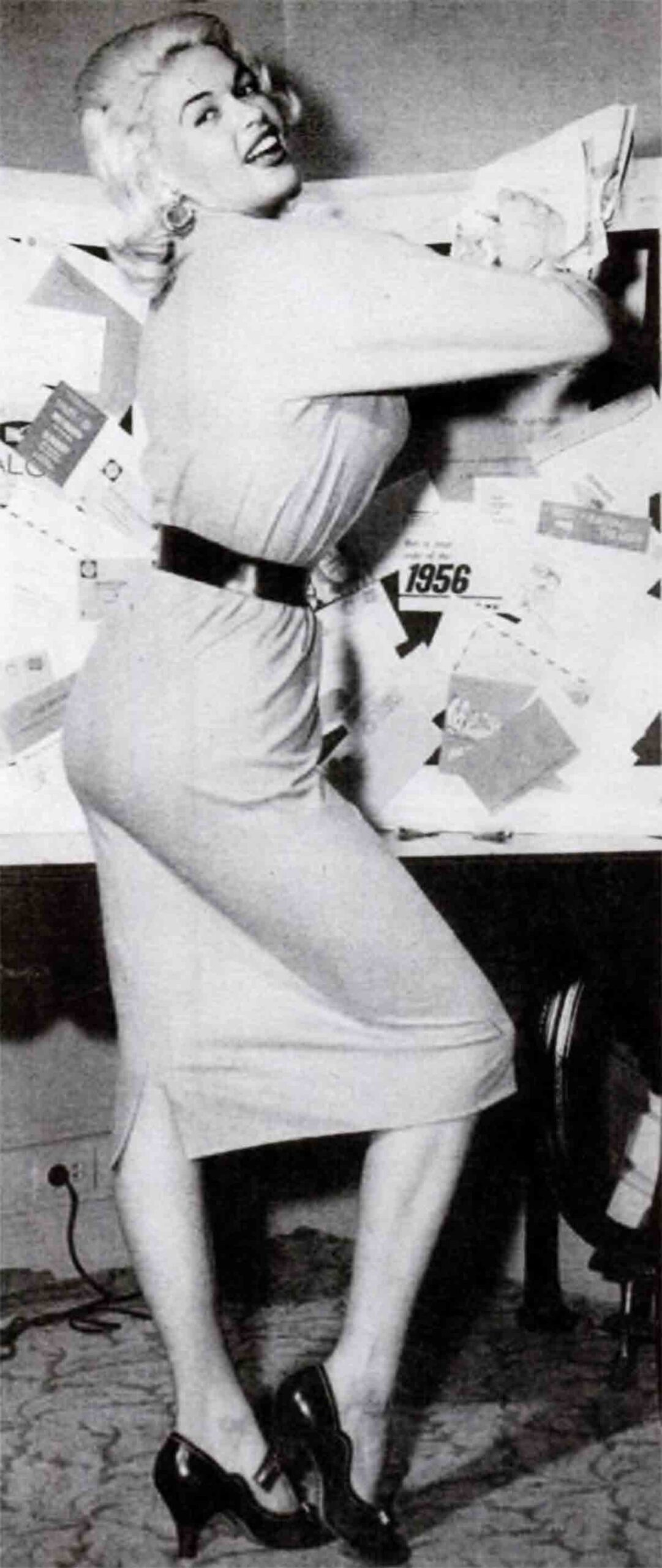

Since she will go practically anywhere and do practically anything that will add to her fame, her days are a mad round of appointments with reporters, photographers, press agents, radio and television people, charity committees, voice teachers and drama coaches, for all of which she is anywhere from a half hour to three hours late. While running from date to date, she feverishly scans the latest editions of all the New York papers for mention of her name; it is possible that a good team of Boy Scouts could track her through the day just by the trail of discarded pages of the Journal-American, Post, News and Mirror that flutter from her fingers on sidewalks, taxi floors and the corridors of studios and radio stations.

The people who try to escort her from place to place have a rough time of it. An escort is likely to find himself carrying her laundry, jumping out of a cab for more newspapers or some orange juice, lending her a comb and pencil, which he will never get back, and trying desperately to make an apologetic call to her next appointment, the nature of which she remembers only vaguely.

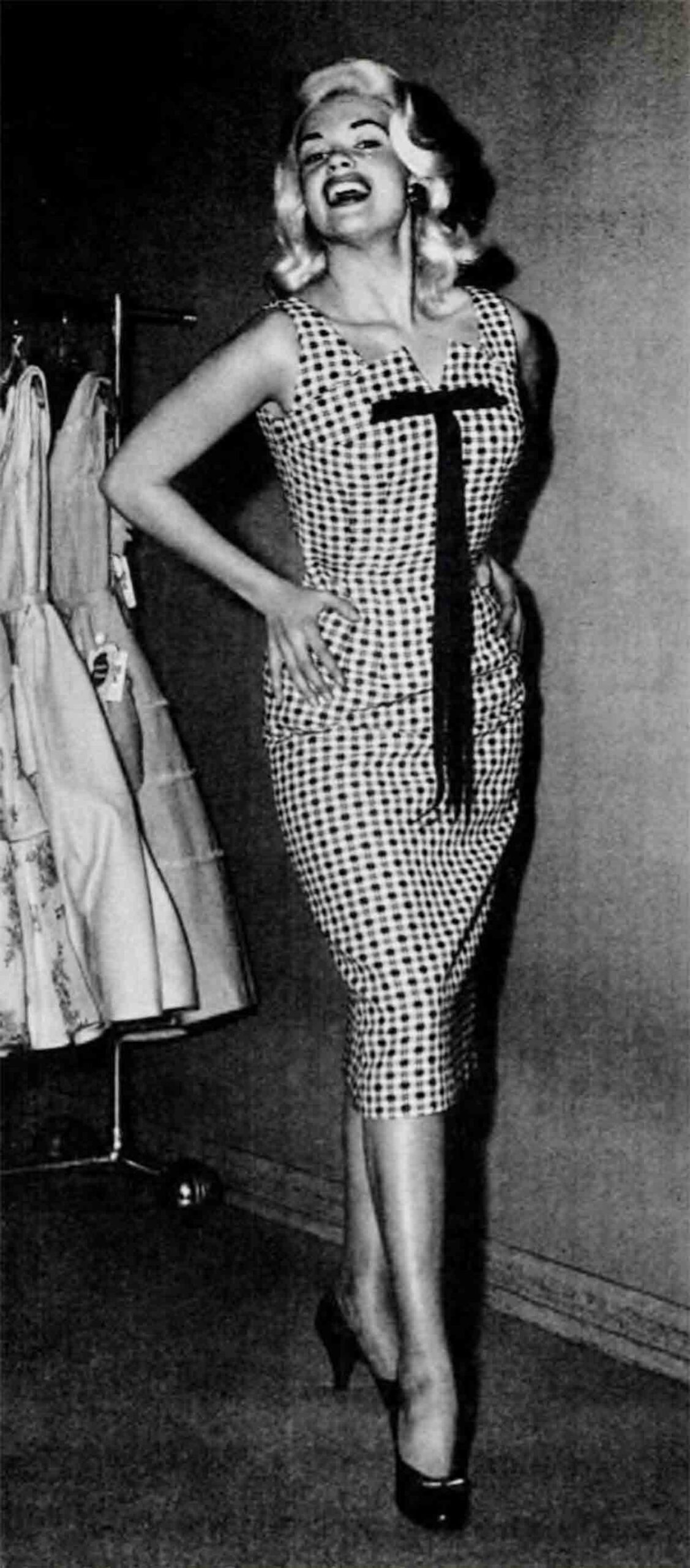

But she has never been late for a performance and in her own unpredictable way she eventually manages to get everything else done that is really important. Her advisers—agent, lawyer and press a sider her a delight to work with, eager, tireless and completely tractable, except possibly on the one subject of astrology. Newspapermen can hardly get enough of her uninhibited conversation and photographers like to take her picture because of her complete candor about what they call cheesecake. Miss Mansfield is well aware that a good figure never hurt any young girl eager into the movies. Indeed she defends her dimensions with a jealousy. When she was fitted for a mink coat recently, the designer took her bust measurement and called out, “Thirty-nine.” “Forty,” cried Miss Mansfield in anguish. The designer consulted his tape measure again. “No, ma’am,” he said, “it’s 39.” Miss Mansfield paled visibly, then said, “Well, this is a tight brassiere.”

Agent Shiffrin is convinced that, if only he can keep her from playing The Loon, he has a great future star on his hands. So are a lot of other people, including many who do not especially admire Miss Mansfield, One Broadway observer said recently, “This girl has absolutely no acting technique and she never will have. But of course she doesn’t want to be an actress—she wants to be a star. I think she’ll make it.” (By Broadway standards, many movie queens do not act at all. They simply manage, on about the 10th or 20th attempt, to hold a 10-second facial expression or recite two consecutive sentences in the way a director with the patience of Job has beaten into their heads.)

One recent afternoon Shiffrin sat at a restaurant table with Miss Mansfield and some friends, discussing her future. He was explaining enthusiastically that he first saw her when she walked unannounced into his. office looking “like a dirigible in a golden dress.” He went on to say that there are two kinds of Hollywood actresses: the high-brow ones like Katharine Hepburn, who appeal to eggheads, and the low-brow ones like Dorothy Lamour, who appeal to truck drivers. The high-brow ones, he said, have to stay on the ball every minute, and are in constant danger of oblivion at that, for the typical movie audience is by no means composed of Phi Beta Kappas. “When it comes to straight box office,” said Shiffrin, “give me the girl who’s really primitive.”

Miss Mansfield nodded gravely and went into her characteristic sigh, throwing back her shoulders and taking a long, deep and spectacular breath. “I’m primitive, that’s for sure,” she said.

No other actress has ever made that statement.

THE END

—BY ERNEST HAVEMANN

It is a quote. LIFE MAGAZINE APRIL 1956