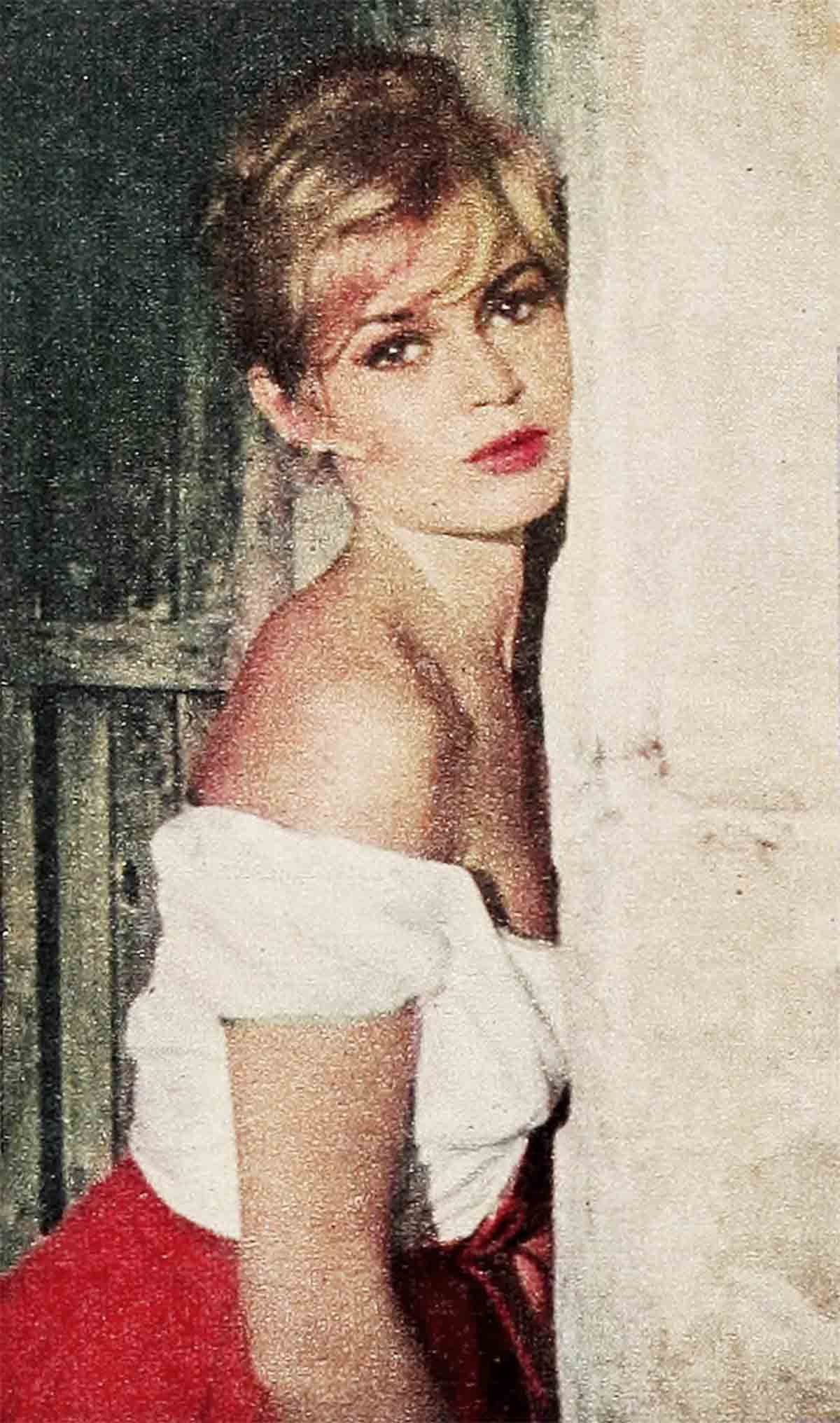

The Shocking Life Of Brigitte Bardot

In many ways this story is a first for MODERN SCREEN.

It is, of course, our first story about Brigitte Bardot.

It is our first story about an actress who has never appeared in an American-made movie.

And it is the first story we have ever printed about a girl as frankly, as un-ashamedly unconventional as ‘The Sex Kitten.’

But in one way, this is a story as old as beauty—as old as the stories we ran in the ’Thirties about Greta Garbo, in the ’Forties about Claudette Colbert—and in the ’Fifties about Marilyn Monroe. Or if you like, it is only as old as this year’s stories of Kim Novak.

For all these women have lived the same story. All these women, blessed with beauty, have been cursed with the same terror, have awakened in the night crying from the same nightmare: afraid that the world will suddenly discover what the beautiful women have believed all along—that they are not beautiful at all.

That is the tragic secret that made Garbo, still young, become a recluse, give up movies, refuse to wear make-up or even walk in the streets without heavy black veils over her lovely face. That is the fear that made Claudette Colbert, ordinarily the most obliging of women, a demon in front of the cameras— fighting for just the right angle, just the right profile, until she was the gossip of New York and Hollywood. That is the reason—the only reason—behind Marilyn Monroe’s famous latenesses; she spends those extra hours before her mirror, desperately applying make-up to what she considers a disfiguring ‘bump’ on her nose, arranging and rearranging her hair to cover her “bad, bad face.” And that is why Kim Novak permits herself to be criticised, even laughed at, for the long minutes she spends staring at herself in any mirror she happens to pass, why she cannot seem to tear herself away from her own image, gazing back with fear-filled eyes.

And it is that which has made Brigitte Bardot, the youngest and most desired of them all, a divorcée, a self-styled “shocker,” and an attempted suicide at the age of twenty-three. . . .

This is her story. Brigitte Bardot was born in Paris. There were, it is true, more beautiful babies born that day, but if her parents were disappointed they hid it well. They had, besides, other things to think about. Papa was a manufacturer, concerned greatly with the technical problems involved in marketing liquid oxygen. Mama, who operated a dress shop and was known, even in Paris, for her personal chic, was pleased to be getting her excellent figure back. There was no lack of money, no lack of care for Brigitte. She was to have the best of everything.

But something was wrong. As Brigitte grew from baby to little girl, even the best hairdresser couldn’t get her lank blonde hair to curl. The best dentist could only report that there was no infection in her gums that gave her bottom lip that swollen look. She was born that way, and that was all there was to that.

Make the best of it

Mama and Papa sighed philosophically. It appeared that little Brigitte would never be a credit to the dress shop, clothed in blue velvet, showing off to the customers. It appeared that Papa had better keep his photos of his baby daughter in the desk drawer when important clients visited his offices in the factory. But so what? She was still their daughter, still their Brigitte, and they loved her. She would always know that, and nothing else would matter.

But it is hard to keep the facts of life from a child, even when you insulate her in an elaborate nursery and make sure her nurse finds only the finest children It’s hard to keep a little girl from creeping off into a dark corner to torture a stray lock of hair around a dampened finger, praying that just once it will curl like Shirley Temple’s. It’s hard to keep a little girl from looking at her face in the mirror instead of at the pretty dresses Mama brings home—looking and looking—and turning away in hate.

She grew up lonely and frightened. The world, to her, was full of pretty girls—and she was the only ugly duckling. She hid her scared eyes behind glasses. She envied the others, the handsome and assured youngsters she played with, so much that she couldn’t bear to be with them. “I detest them all!” she said angrily when Mama, concerned. asked why she was home so much when other girls were roller-skating, tea-partying together. “I like to stay home. So I’m lazy—so what?”

But Mama was not to be deceived forever. It was not good for a child to be always indoors, brooding. “I do not mind what you choose to do,” she told Brigitte finally, “but you must do something to get out of the house, be with people. Perhaps you would like to take a course. Singing? Painting? Dancing? I give you your choice, ma chére. But you must pick something, and do it.”

Brigitte couldn’t draw, and she knew it. The idea of singing, standing up before rows of staring eyes, was too horrible to contemplate. But dancing—that wasn’t so bad. There would be a whole crowd making the same movements, and she would perhaps be at the end of the line where no one would notice her.

So, at the age of ten, Brigitte Bardot bought her first tutu and ballet slippers—and walked in them into a new world.

Unaccustomed joy

The obvious had happened. She had discovered her body. And that—oh, that was quite a different matter from her swollen-lipped face. Even at ten, her body had grace. Her body had charm. Her body could do things that Brigitte had never dreamed of—twirl, leap, bend, soar! Far from hiding her at the end of a line, her teacher dragged her out to the center of the floor over and over again. “Watch how la petite Mlle. Bardot does it,” he would admonish the other children. And Brigitte, her face flushed with an unaccustomed joy, would float as if she wore invisible wings on her straight little back.

When she was thirteen she, and a hundred and fifty other girls, took the test for entrance into the National Conservatory of Music and Dancing. For the next week, her parents walked almost on tiptoe around the house—the slightest harsh word would send Brigitte into nervous tantrums, the suspense had her so keyed up. At the end of the week, Mama walked into the old nursery—now Brigitte’s bedroom—and found her daughter in tears on the bed, an official-looking letter crumpled in her hand.

Madame Bardot clucked her tongue sympathetically and reached out to take her daughter in her arms. “There, there. You’ll try again next year—you’ll pass next year.”

But the face Brigitte raised to her was radiant below the tears. “I did pass! Seven other girls and me!” The tears were of joy.

She was going to be a ballerina!

For the next two years she lived and breathed dancing.

And at school she was still tongue-tied Brigitte, sure she was being laughed at behind her back, snickered at whenever she stood up in class to answer a question, because of “my ugly face.” But at the Conservatory—there she was La Bardot, star pupil. There no one looked at her face—their eyes followed her flashing, graceful body as it whirled through intricate routines. There her body was queen.

When she was fifteen her parents finally gave in to her pleas—they allowed her to drop out of her academic courses and concentrate entirely on dancing.

And so, for a while, she was happy. But then a strange thing suddenly happened.

“I need money,” said Brigitte Bardot to one of the girls at the school. Why, she didn’t say. Had the bottom dropped out of the oxygen factory? Had the customers lost interest in Mama Bardot’s particular taste in clothes? Her friend wondered, but didn’t ask. If Brigitte needed money it could only be for one thing—to stay in school. And that she must do. So she looked her over thoughtfully.

“Well, you can’t type and you can’t take shorthand, and you mustn’t take a job standing all day selling behind a counter—you would ruin your feet. So there’s only one thing. You must model part-time. I do it often. It pays very well.”

Brigitte stared at her dumfounded. Model? The girl must be mad. Models were beautiful, not ugly. She would be laughed at instantly. But she couldn’t say so out loud. So she accepted silently the copy of the fashion magazine offered to her, took down the names of some agencies, and promised to think it over.

Interesting, yes. Photogenic, yes. And they had good figures. Brigitte crept out of bed and stared at herself in the mirror. For the first time she examined her body less for what it could do on the ballet stage than for what it was. And she had to admit—it wasn’t bad. For all her exercising, her legs had not grown knotty as most dancers’ do, her bosom had not grown flat. Indeed, for a fifteen-year-old girl—she was, you might say, well-developed.

“All right,” said Brigitte, shivering in the chilly room, “I’ll try. If they laugh at me—so what?”

But they didn’t laugh. They looked at her perhaps a little doubtfully, and then a man said, “Here. Go change into this and come back.” He handed her a scanty bathing suit, showed her a dressing room. Behind the curtained doorway, Brigitte climbed into the suit. She took a deep breath and walked out.

And they very definitely didn’t laugh.

The road up

The bathing suits got briefer and briefer, the nightgowns she posed in flimsier and flimsier. It never occurred to Brigitte that she was doing anything odd, appearing half-naked before strange men, posing provocatively. It was so simple to her. Her body, her great blessing, was getting her what she wanted, as it had since she discovered it when she was ten. It so enchanted these men that they never seemed to notice her face, seemed scarcely interested in it at all. Her body was earning the money she needed to go on with her dancing. It was wonderful, truly wonderful.

And even more wonderful when one of the photographers fell in love with her.

His name was Roger Vadim, and he was a photographer-journalist for Paris-Match. That alone was enough to impress Brigitte, for Paris-Match is the French equivalent of Life Magazine, and to be pictured in it—is success. But there was more to Roger than that. He was older, handsome, and ambitious.

“I am going to be a film director,” he told Brigitte at their first meeting. “I am going to make movies that will be shown all over the world. I will be very rich, very famous.”

She believed him. Nervously, she invited him to a little party at her house. There would be some friends from the ballet school. To her amazement, he said yes.

Which came first that night—love, or the great idea? Neither of them knew. Brigitte danced with her friends, flirted a little with one of the boys from school who had taken to following her about a bit. But from the corner of her eye, she watched Roger, and in a corner of her mind she wished that the others would leave early—and Roger would stay. As for him, he watched only Brigitte. There was something about her—charming, enticing, innocent and provocative at the same time. She moved her body like a young cat— yet she seemed to have no idea that every man in the room was entranced by her. Her face glowed with youth and beauty, her lips pouted adorably—and yet he had heard that she thought she was homely as a hag.

If she were his, he would teach her how beautiful she was, how precious. He would—he would make an actress of her, a movie star, a dream of all men. If she loved him too, he would—

For he had said everything so exactly right. He had told her his brilliant plans, and she cried out, “You are crazy! A movie star, me? With this face, this wrinkly nose, bulging lips?” And he had not told her the truth—that she was beautiful. That, she wouldn’t believe; not yet. Later she would see it herself, gradually, as the whole world fell in love with her. But now he said only, “They’ll never notice your face, Brigitte. We’ll show them your wonderful body—”

Mama and Papa smiled indulgently when Brigitte told them she and Roger wished to marry. They liked Roger, they would have no objections if, in three years, they still felt the same way. Surely they would not mind waiting until Brigitte was eighteen?

It seemed reasonable to them both. It would give Brigitte a chance to grow up, Roger a chance to learn the art of film directing.

Three years later, on Brigitte’s eighteenth birthday, both dreams came true . . . it seemed. They were married, and they began work on the first Brigitte Bardot picture, directed by Roger Vadim. It was not a low, but a tiny-budget picture—but it was theirs. While they worked on it, they were happy. Roger coached Brigitte in every scene—every pout, every wiggle, every flirtatious glance was carefully directed. Brigitte adored him. She would wake in the night to stare silently at the wonder of having him lying beside her. When money ran out, her parents sent some, and the Vadims ate well for a week. They were happy.

Then the picture was completed. Brigitte saw it. That night when Roger got! home, his wife was nowhere to be found. Worried, he called her parents, her friends. No one had seen her. His worry turned to terror. In a borrowed car he searched the streets of Paris until he found her—leaning on the rail of a bridge, sobbing as if her heart would break.

“I’m so ugly,” she wept as he bundled her into a coat and drove her home. “So ugly. . . . I never knew just how ugly . . . like an old hag. . . .”

He couldn’t get her to stop crying.

The road continues

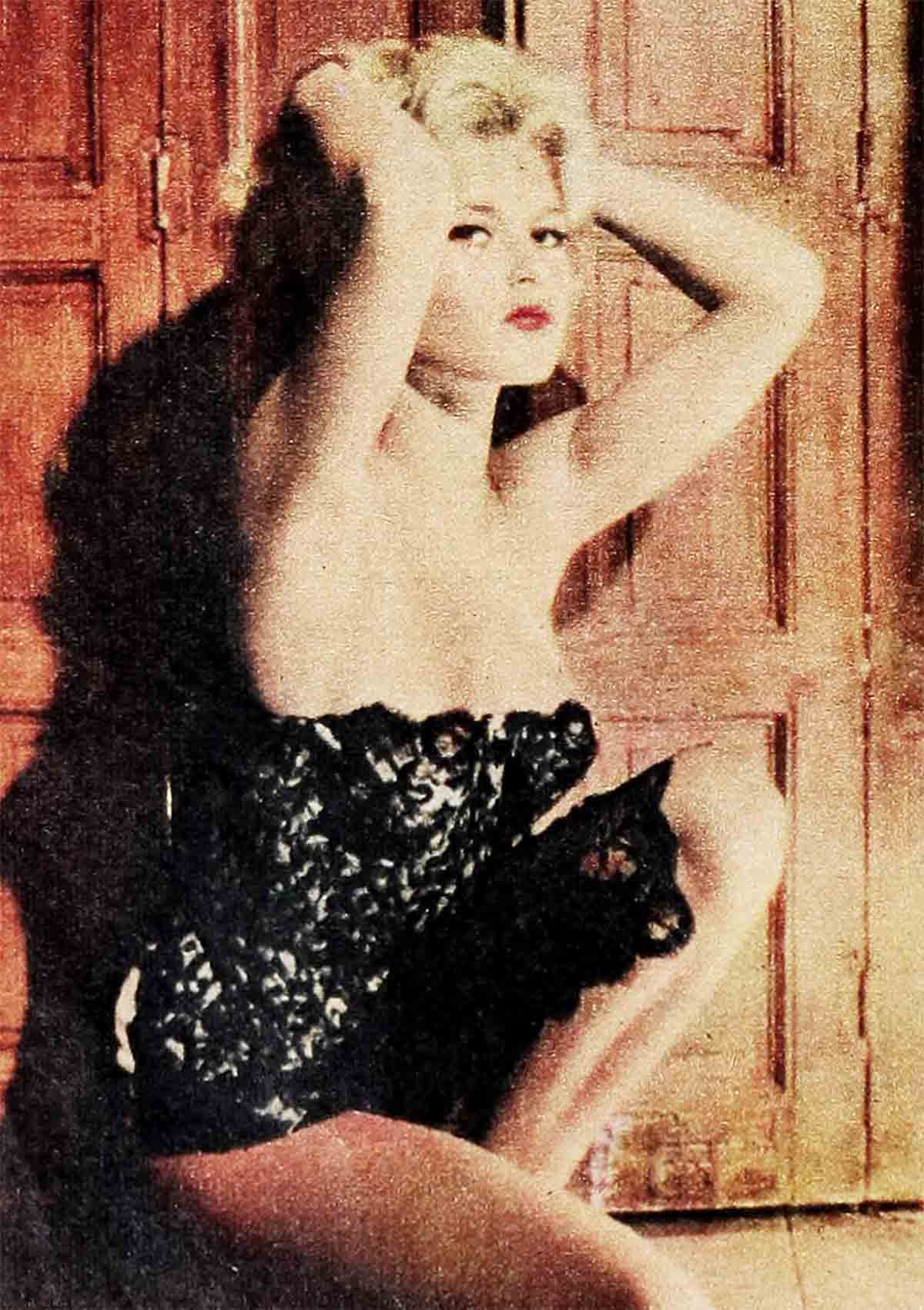

But she went on making movies, trying to get more work whenever a film was completed. It would be wrong to say that Roger forced her into a career she hated—entirely wrong. For like the other beauties who have lived with her fear, Brigitte constantly tried to prove to herself that she was wrong and everyone else was right—she was pretty. She showed herself over and over, hoping that the miracle would happen: someone would say, “You’re beautiful!” and she—she would believe it. And in the meantime, she had her “wonderful body.” In that, she did believe. She put it on display as much as the law would allow—and in France, that’s a good deal. She developed, under Roger’s tutelage, a wiggle that would have made Monroe blush scarlet.

Naturally, she became famous.

Not outside of France—her pictures were banned in almost every country. But in France, by the time she was twenty-one, she was queen at the boxoffice, queen of the fan-mail, queen of the dreams of a million men. Roger won success not only because of her, but because of his own talent as a director. They should have been ideally happy.

They were not To Brigitte reading her own publicity, seeing her name in lights, her face on the screen, it was as if she had climbed to a high place on a shakey ladder—as if any moment she would look back and the ladder would be gone, the world would be saying, Ugly girl, how you have deceived us! and she would fall faster and harder than she had climbed. On the set, she went further and further with her exposure of herself, her handling of risqué scenes. Offstage the quotes she gave out to newsmen were carefully planned to make her as sexy as possible:

“I do not own a bra. If the weather gets very, very cold, then maybe I put on a little thin pair of panties. Otherwise—

“I do not like lipstick. I like to kiss, and if I wear lipstick it makes a big mess for the man and me.

“I only play myself on the screen. That is why I like free, wild, sexy parts.”

She threw herself into a dozen activities to keep herself from thinking. She developed a tremendous love of animals, once tried to persuade Roger to adopt a goat—to live in their apartment’s bathroom. She read murder mysteries the ‘way a chain smoker smokes. She developed odd fears—of men in uniforms, of fires, sudden death. And more and more often, there were the lonely walks in the night, the tears on the bridges of Paris.

Faced with this new, tense Brigitte, Roger no longer knew the right things to say. Brigitte would walk into the house, her hair uncombed, her makeup askew. A second later she would be leaving again.

“Where are you going?”

She would turn, looking at him with a peculiar expression. “I’m going to a dance with one of the extras from the movie. A boy.”

Roger thought he was proving his love. “All right. Have fun.”

But to Brigitte all it meant was that he had finally realized that she was nothing, that he no longer cared. Why should he? Working all day in the studio, he had plenty of chance to compare her to the really pretty girls. She was absolutely confident that he had found one for himself.

In the end, he did.

Roger was kind

When the marriage broke up, these two people who had understood each other so well no longer had even an idea of what the other was thinking. “Brigitte may tell you,” Roger said in an interview, “that we broke up because I was jealous. But that is not true. I was never jealous of her. Maybe I should have smacked her the first time she looked at another man. But she always looked so innocent.”

And the papers that carried that story also carried a quote from Brigitte, an unusually honest one. “How could I believe he loved me? He was never jealous. . . .”

There was a long separation while the divorce—a difficult matter in France—was arranged. On the day the final papers were served, Roger Vadim’s pretty girl friend gave birth to his baby, a daughter, in a Paris hospital.

Brigitte, interviewed by excited reporters, gave out one of her typical statements to the press. “Of course I knew about the baby. I am very happy for them both. I have bought a beautiful crib for a present—and I have asked to be godmother if they like.”

Even in France, that made headlines.

The next day Brigitte had another announcement to make. “It is wrong to blame the break-up of my marriage on my husband. You see, I fell in love with another man.” Who?

“Jean-Louis Trintignant. It is funny, no? You see, he plays my lover in And God Created Woman, so Roger must direct us in the love scenes together!”

Very funny, no.

This reality

What has developed between Jean-Lou and Brigitte since that day is real enough. Real enough so that he, a handsome young actor, has finally asked his estranged wife for a divorce—they were separated before he met Brigitte . . . and was refused firmly, for his wife is an ardent Catholic. Real enough so that Brigitte has taken an apartment where she can cook for Jean-Lou, wait for him when he is away on a picture assignment, and give out quotes like, “We have fallen very, very much in love. We are acting like mad people. There is no organization in our lives. In any case, what other people think doesn’t worry me at all.”

And real enough so that, according to her closest friends, only weeks ago, Brigitte attempted to end her life with sleeping pills.

That is not the end of the story. The attempt failed, and was of course denied. Brigitte took off on a skiing tour in a secluded village. And Jean-Lou with some understanding told the press, “Underneath, Brigitte has a deep sensitivity. Beneath all that varnish, there is a true woman, one who is self-tortured and unhappy. I say to myself, This girl is lost, and maybe I can bring something to her.”

Maybe he can.

Maybe some day he will be able to bring marriage to go along with his love, and a sense of security and some ‘organization.’

Maybe he will even be able to bring her the greatest gift of all—the greatest gift to the Garbos, the Monroes, the Brigitte Bardots—the gift of belief in themselves, and in their beauty.

THE END

—BY HÉLOISE NOUVELLE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1958