Elvis Presley Said To His Father

Elvis moved restlessly on the bench at the Frankfurt airport. He looked at the special pass he had received for the afternoon. This was the first favor he’d asked since he’d been in Germany; the afternoon off so that he might be on hand when his Dad and Grandmother flew in from the States. Even though it’s not every day that a fellow’s family come across the ocean to visit him, he’d been reluctant to ask the C.O. for a pass. The other fellows in his barracks were just beginning to accept him as just another soldier, not a privileged character, and he didn’t want anything to spoil it. But he knew that Dad and Grandma would feel lost if he wasn’t there to greet them, so he’d asked for the pass.

AUDIO BOOK

Elvis suddenly got up and walked over to the flight information desk. Frankfurt is an international airport and the man at the desk, fortunately, spoke English. On days off, Elvis had been taking German lessons from a young girl he had met, but somehow the hard “ch” sounds of this strange language just didn’t go well with his own soft Southern drawl. And he didn’t dare to try his German on anyone but his teacher.

“Sir, could you please tell me if Flight 104-A is on time?” Elvis asked.

“Right on time,” the man answered, “Be here in about seventeen minutes.”

“Thank you. And could I trouble you for one other thing? Do you have a list of the passengers?”

“Yes.”

“Well, would you mind checking to see if two people are on the plane? Their name is Presley. Vernon E. Presley. And Mrs. Minnie Presley. Thank you.”

The man ran his finger down the list and then said, “Ah. Here they are. Presley. Vernon and Minnie.”

Elvis thanked the clerk again and returned to the bench. He watched a German family—three kids and a father and mother—crowd around a phone booth. One of the kids, a little boy, was trying to push into the booth to be with his father, and the mother was tugging him back. The whole family seemed to be talking at once. They were talking too fast for him to understand even one word, but the scene didn’t need words: It was the same in any language.

Somehow it reminded him of the call he had made to Memphis a week or so before. He had stood in line at the PX, waiting his turn at the phone. He had placed the call earlier in the day so as not to tie up the one long-distance phone too long. So, it took only a couple of minutes before he heard his father’s voice on the other end of the wire.

“When are you and Grandma coming over, Dad?” he asked. “I miss both of you very much.”

His father had sounded so sad on the phone, sad and kind of flat—as if he just didn’t care. He gave all sorts of reasons why they shouldn’t make the trip, but the one reason that really counted he never mentioned. His dad had never been able to say what was in his heart.

So he had to answer his father’s objections. And in one rush of words he said, “Look, I do get time off and I can be with you, especially on those nights when I’m not on duty . . . and Grandma can make the trip . . . she’s stronger than me. I’ve already made reservations at a hotel in a place near the base. It’s in a town called Bad Nauheim . . . but it’s not bad it’s good. A couple of rooms in a hotel, with a kitchen even—where Grandma can cook.”

He had paused for breath for a moment but there was no sound from the other end. It was a family joke, it always got a laugh, about Grandma’s cooking. Not that she couldn’t cook; she certainly could. But even though his Dad and Ma had been married twenty-five years, and he and Dad had loved Mas cooking, Grandma Minnie—Dad’s own ma—was convinced that Vernon wasn’t getting the right sort of victuals, that her daughter-in-law Gladys just wasn’t a good enough cook for her boy. The fact that Dad was tall and husky—and always came back for second helpings at every meal—didn’t seem to make a bit of difference.

“Dad, are you still there?” he said into the phone.

“I’m still here,” his father answered.

And then he had said what he didn’t want to say, but had to. “Dad . . . Dad . . . one of the last things that Mom said to you—you told me so yourself—was that you and I should always be together. And you promised her we would be. Remember? Well, I want you to come. Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without you and Grandma here. And Mom would have wanted it.”

There were a few seconds of silence and then his father’s voice, huskier than usual, said, “All right, son, Grandma and me will be there.”

“Achtung! Achtung!” the words blared out from the waiting-room loudspeaker and Elvis jumped to his feet. From the information desk the clerk smiled at him, nodded, and pointed towards the door that led out to the field. Elvis hurried to the entrance and ran to the barrier that surrounded the runways. The Constellation landed. It touched ground, slowed abruptly to a stop, turned around and taxied towards the barrier. The portable steps were pushed out next to the plane, the side door opened and the passengers began to descend.

Ah, there was Dad and Grandma. Grandma’s sixty-five but she’s walking like a girl, as if she had just been out for a spin in a car. But Dad. Dad, he looks gray and tired . . . so tired.

Elvis lifted his grandmother off her feet as she came through Customs.

Put me down. Put me down,” she laughed. “I’m not one of your girlfriends. Why, I’m old enough to be … to be your grandmother. Besides you’ll muss my new clothes.”

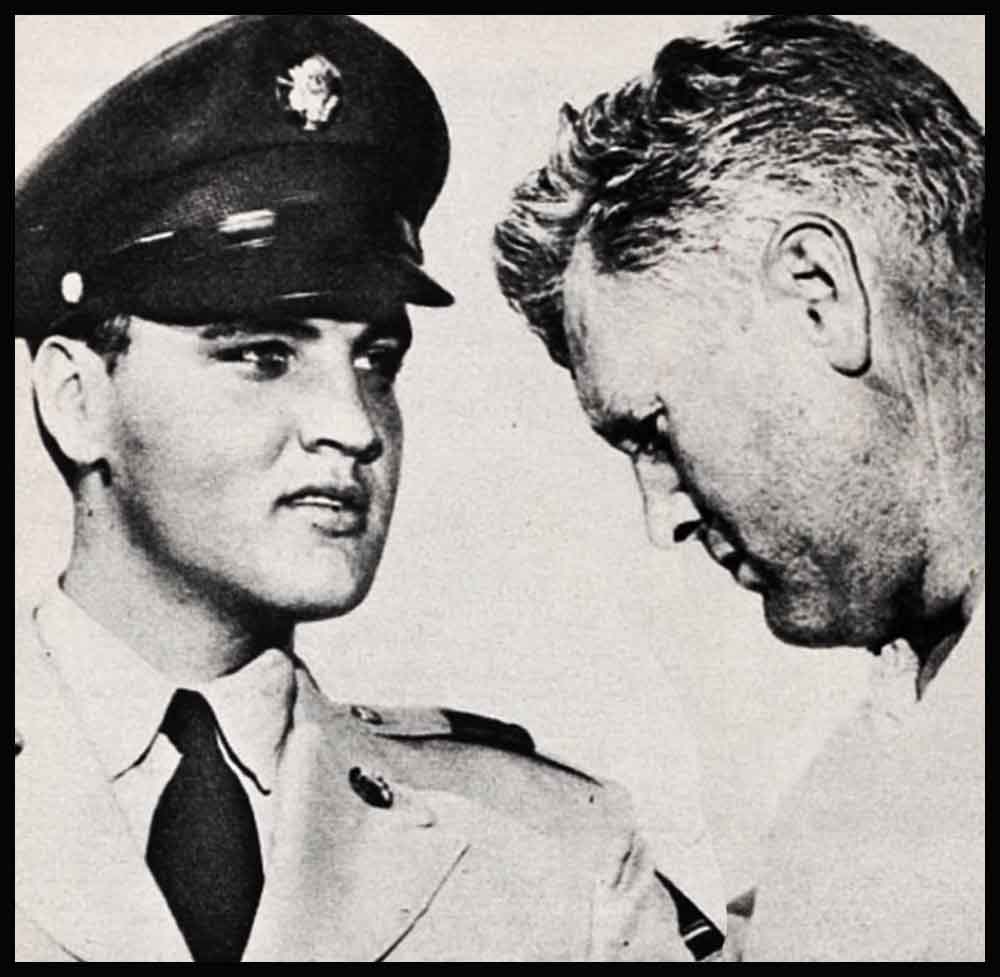

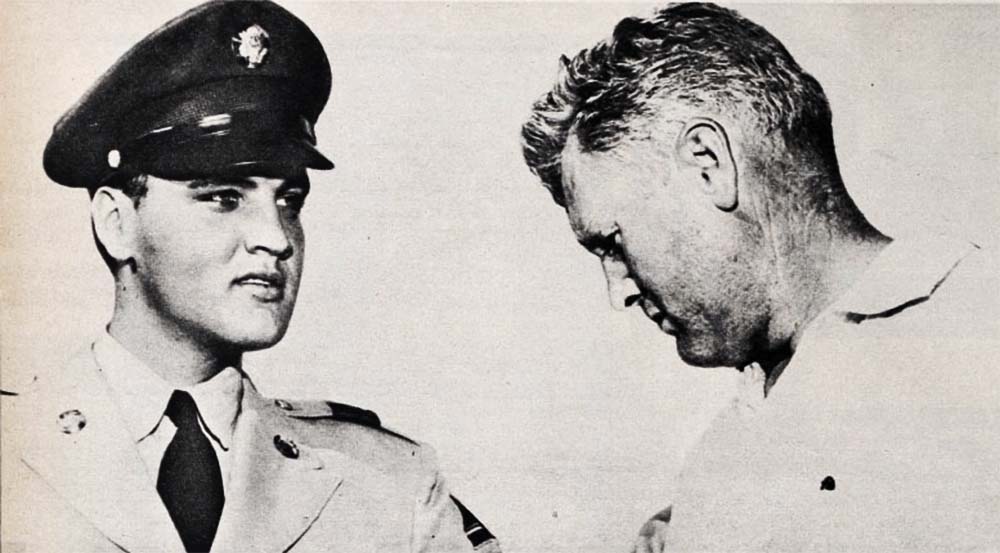

“Just like a woman,” Elvis said, and set her gently back to the ground. And then he turned to greet his father.

Vernon Presley pushed his son on the shoulder Elvis made a gesture as if to push him back, then let his hand fall. “The last time I hit you back, you couldn’t move your arm for a week,” he said.

“But you were only eleven then,” his father said, laughing. “You’ve gotten weaker ever since.” And then they embraced.

In the cab on their way to Bad Nauheim, Elvis and his grandmother did most of the talking. Vernon Presley gazed out of the window, seeing but not-seeing at the same time.

“You’ve lost weight,” his grandmother said. “You father says there s a kitchen where we’re staying. I’m going to cook you some real Tupelo meals.”

“But I’ve gained weight,” Elvis laughed.

Elvis’ father looked at his son. “You haven’t changed. Not a bit.” And then he smiled.

The next day Elvis phoned his dad and grandmother twice when he had a break from his duties. He arranged to drive over from the base at Friedberg to Bad Nauheim to eat dinner with his family. Minnie Presley had spent hours in the kitchen, but she wasn’t satisfied. “Would you believe me, we couldn’t find hominy, corn pone, or okra in the whole town.”

After dinner, Elvis had to go back to camp. He told his father and grandmother he would see them the following night, and that he would take them to a restaurant for some “real German food.” “Not that it’s as good as yours, Grandma,” he hastily added, “but it’s good for us Americans to get to know other people.” He also told them that the Army had scheduled a press conference for all the Presleys. “You’re kind of unofficial ambassadors from home,” he said, “and the Army folks here want to show you off.”

The press conference went off well. Minnie Presley had had her hair fixed that afternoon and she had put on her best dress. “I never felt so important in my life,” she laughed, as the reporters asked her questions and snapped her picture. One of the newspapermen asked Vernon Presley how long he planned to stay in Germany.

“I would say it probably will be a temporary stay,” he answered. “But we like Germany. The people are okay and very nice.” Shorty after that the press conference ended.

The three Presleys ate dinner in a little restaurant near the hotel. Then Grandma complained about feeling a little tired “from all the excitement” and they took her back to the hotel.

“Sleepy, Dad?” Elvis asked his father.

“Not very,” Vernon answered. “Besides, I don’t sleep too good these days.”

“Me neither,” Elvis said. “Let’s take a walk.”

Father and son strolled through the streets of Bad Nauheim. They came to a little park and sat down on a wooden bench. For a while they watched the people passing. Couples would come down the path in the darkness, be silhouetted for a second in the glow of a lamplight, and disappear again into the darkness.

“Everybody seems to have someone,” said Elvis’ father, and then he buried his head in his hands.

Elvis reached out towards his father and then drew back. And suddenly he began to talk, slowly, with great effort. “Back there at the press conference . . . you said you might not stay in Germany long. I wanted to stop you and tell you that you must stay. But I couldn’t. Not in front of all those people. Sure, Mom wanted us to be together. She’d especially want this at Christmas. But that’s not the main reason. The main reason . . . well . . . the main reason is that I need you. I want you here.”

Vernon Presley sat up slowly on the bench and looked at his son. He started to interrupt but Elvis went on anyway, as if he wouldn’t be able to say all he had to say once he stopped.

“Grandma told me how it’s been with you. Walking from room to room in that big house in Memphis. Walking and walking and walking. The same house but not the same. Not the same without Mom there.”

Again Vernon Presley tried to say something and again Elvis stopped him. “Well, it’s been hard for me too. Sure, I get up early in the morning. Earlier than I ever did before in my life. And I work hard all day. But it doesn’t matter. I go to bed when the others do. They’re asleep as soon as they hit the sack. But I stay awake . . . I think of Mom . . . and I think of you. I try not to. I try to go to sleep, even try counting sheep. But it doesn’t work. Then I try to remember the names of all the places I’ve ever sung in. And just when I’ve gotten started, I’ll remember Mama’s face.”

Elvis stopped and looked into the darkness, and then he went on. “You taught me to pray—you and Mama. And you taught me that God has a reason tor everything he does . . . that death isn’t the end and life goes on. I believe that. Mom believed it. You must believe it too.”

Vernon sat quietly. Then he spoke. “I was remembering last Christmas. Last Christmas in Memphis. And how Gladys said that no matter what, at Christmas we must always be together. And now she won’t be here.”

“But she will,” Elvis answered. This Christmas you, Grandma, me and Mom will be together. We can’t forget her, not for even an hour, so she is with us, she will be with us. As long as you and I are together, she’s here. Please stay.”

“I never heard you put so many words together so good since you tried to convince your Ma you didn’t steal those Coke bottles when you were five,” Mr. Presley said, smiling a little. “There’s certain things I should be taking care of at home. But if I can put them off, or get someone else to do them, I’ll stay.”

He shook his head. “That’s not the way I want it to sound at all. You say you need me. I know I need you. We’ll stay . . . if I can swing it back home.”

Elvis smacked one hand against the other, like he always did when he was excited. “Do you know what I’m going to do? I’m going to buy a house for us here. Don’t laugh. I’m serious. No, I won’t be getting special treatment. Anyone in the outfit can live off the post when he’s not on duty. I’ll be with you lots of nights and on my days off.”

His father interrupted him. “Do you think there’ll be snow by Christmas?”

“You’re trying to change the subject,” Elvis said. “Yes, there’ll be snow. There better be snow. I’ve never seen snow at Christmas.”

“I haven’t either,” said his dad.

“We’ll,” said Elvis, laughing out loud, “there’ll be snow all around our house. And early in the morning on the day before Christmas we’ll go over to one of the villages and go to church. That’ll be about four or five in the morning. All the villagers will be walking along with lanterns to the church.

“We’ll set up a tree in the living room of the house. And we’ll put candles on it— not light bulbs—and lots of tinsel. Then we’ll put the presents around it. Not wrapped. That’s the custom here. Maybe Frieda—that’s the girl who’s helping me with my German—can get away from her family and come over too.

“We’ll eat at about six. Fish—carp from the Rhine—and stuffed goose and red cabbage and mashed potatoes and Christmas cookies.”

“If I know your Grandmother,” Mr. Presley said, “by that time she’ll have found out where to get blackeyed peas and okra and corn pone . . . and we’ll have that, too.”

Elvis laughed. “After dinner, well go into the living-room. But before we go in, we’ll say the Lord’s Prayer . . . people here call it the Voter Unset . . . and then we’ll sing carols like Mom and I did last year. Some of the boys from camp will come. When we’re done carolling, we’ll open the doors and go into the living room. You’ll light the candles and wrap a piece of bread in silver paper and put it on the tree. That’s so we’ll always have bread in the year to come. Then we open the presents.”

Elvis’ father shivered a little. “Maybe it’s going to snow before Christmas,” he said softly.

They got up to go. As they passed the village square, they saw a roped-off section with a load of straw on the ground “They get started way ahead of time here,” Elvis said. “They’re going to build a small manger there, with real live animals in the little barn. Frieda tells me that Christmas is a very religious season here. It’s really three days—the 24th for celebration, the 25th for prayer, and the 26th, St. Stephen’s Day, for prayer and celebration.”

They walked on, stopping finally in front of the hotel. “All those things you’ve said about the way it is here at Christmas, Elvis. Your mother, your mother would have loved it.”

Elvis clapped his father affectionately on the shoulder. “I know,” he said.

Mr. Presley paused at the entrance to the hotel and smiled. “Good night,” he called. “Good night, son.”

“Good night, Dad,” Elvis answered. “Sleep well.” He walked back to camp, sniffing at the sudden crispness in the air. Perhaps there really would be snow by Christmas.

When he arrived at the barracks, he went to his bunk, undressed, slipped under the covers, and for the first time in a long while he fell asleep as soon as his head hit the pillow.

—JIM HOFFMAN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1959

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments