“Look, Kid, How Stupid Can You Be?”

That’s what I thought to myself the other day: “How stupid can you be?” I was reading a newspaper story about a teenager who had been arrested for stealing parts from parked cars. “Lots of kids do what I did,” this kid was quoted as saying. “The only thing wrong about it was getting caught.”

It made me so sore to read that statement made by a kid I didn’t even know, that I sat there fuming, wishing I could get my hands on him and shake some sense into him. I wanted to shout at the foolish lad, “How stupid can you be?”

AUDIO BOOK

I feel I have a right to talk like that because I was once pretty dumb about such things myself. I was one of those “smart” kids who thought it clever to break the law. But I have news for that youngster, and any others like him. It isn’t smart, it’s stupid. I found that out the hard way.

I have since had to pay the price for every mistake I ever made. I had to bring shame and suffering to the people who were close to me when I admitted to the world that I had a prison record. And when I become a father, I’ll have to pay again someday, because I’ll have to tell my child the truth about my life, before somebody else does. Children can be cruel, and it’s entirely possible that some child may say, with unintentional cruelty, “Your father was a jailbird.” I don’t want my child to be hurt for something I did any more than is absolutely necessary.

My child will have to hear it, but I want him to hear it from me. The toughest part is going to be trying to explain to him why I did the things that landed me in jail. At the time, like any lonely, underprivileged kid, I had a grudge against the world. I was going to get away with all I could. Why not?

My father left home when I was a year old. My mother, a beautiful young woman, had to work as a waitress on a split shift in order to support herself and me. I lived with my mother, uncle and grandfather in Santa Cruz, a small town in the foothills of California.

Sometimes my mother was away during the daytime, sometimes at night. She did the best she could, under the circumstances. But she had so many problems of her own. I never felt I could worry her with mine. Nor did I have much of a companionship with my uncle and grandfather. They lived in a mental world that was far different from mine, one I didn’t understand and which therefore didn’t interest me.

Like many kids who get into trouble, I was a lone wolf. I seldom associated with the other children in school or elsewhere.

I got used to being alone. When my folks had company, they’d give me some money to go out and have dinner. I used to go to the local Chinese restaurant and eat there. After that, I wouldn’t know what to do with myself. I knew I was supposed to keep out of the way at home, so I would look for things to do on the Street to fill the time.

I’ve of ten heard the teen-age children of friends of mine complain about parental supervision. They say, rebelliously, “My mother makes me get home by 11 o’clock every night—even earlier on a school night! It’s ridiculous! I feel like a dope when I have to explain to the other kids. Or even worse, to my date!”

That was a problem I never had. Maybe I would have rebelled, too, but I still wish I could make those kids see how wonderful it is to have someone at home who cares deeply about what happens to them. It’s the kids whose parents are too busy or too tired to care when—or even whether—they come home, who get into trouble. In a way, you can’t really blame these kids. As I did, they start looking for some way to forget their loneliness, for excitement. Sometimes they find that excitement by learning to steal.

I began to steal things when I was just a youngster. I stole only little things, but it gave me the thrill I needed. I was getting away with something—or so I thought. Actually, the punishment was there, just waiting to catch up with me.

I didn’t dare bring the stolen money or things home, for my mother would have raised the roof, and probably would have called the cops. So I also got into the habit of staying away from home more and more. Sometimes, without saying a word to anyone, I would run away from home and go up into the Santa Cruz mountains by myself. While other kids were closed up in school rooms, I was hunting for rabbits and fishing for trout.

Those other kids were dumb; I was smart, or so I thought. I didn’t mind too much the licking I got when I’d finally return home. I felt it was a small price to pay for all that fun. When I returned to school, I had to bring a note from my mother explaining why I’d been absent. I didn’t have the courage to tell my teachers the truth, and my mother, wanting me to take the punishment I deserved—and which might have spared me some of the really tough punishment I deserved and got later on—refused to give me a note. So I wrote my own notes, saying I was sick, and forged my mother’s name to them. A habit, a vicious habit, was being formed. The habit of thinking that nothing was forbidden, nothing was wrong—except getting caught at wrongdoing.

What could my parents—what can any parents—do to save their children from making the same mistakes I made? With my own child about to be born, I’ve done plenty of thinking about this, and I believe I know some of the answers.

For one thing, too many parents take their children for granted. At first they cluck and fuss over a newborn baby, then they have to turn back to the everyday problems of earning a living, paying the bills, trying to make ends meet. They want their children to have more than they had. Again and again I hear parents who are too busy to spend time with their children explain this neglect by saying, “But I want to give them things—all the things I didn’t have.”

If those people ever stopped to ask their kids what they want, chances are the children would say, “I want you”

Too many parents don’t spend much time with their children. They’re too tired to play with their children or answer their questions. I’ve heard lots of my friends say to their youngsters, “Just take my word for it and don’t argue. I’ve been through it and I know a lot more than you do.” And then these devoted parents add impatiently, “Now run along and play and let me read my paper.”

It isn’t enough to tell a youngster that he can take your word for it. You have to explain. You have to respect the child’s opinion, too, and listen to it—really listen. You’ve got to help him make his own decision; you shouldn’t ask him to accept yours. When a child is told to “run along” and is not given what he considers a fair shake, he feels confused—and rebellious. I know. I went through it as a child. It was one of the things that left me with a grudge against the grown-up world. I’d get their attention, I vowed. They’d see, they’d be sorry for brushing me off as though I didn’t matter.

Because of the experience I myself have had, I have resolved that, when I become a father, I will spend plenty of time explaining things to my children, showing them why they should do certain things. I know how dangerous it is to set kids free to try out things for themselves, without knowing what the consequences can be.

I never cried as a child. I kept most of my feelings and my problems to myself, because I didn’t really think anyone cared about me. It’s a lot easier to help a child if he learns to talk out his problems. I want my child to know that he can come to me with any difficulty and tell me about it, no matter what he’s done or how bad it seems. I want him to know that nothing he might do would ever change my love for him. We all make mistakes. once they’re paid for, we can forget them and go on. Nobody thinks less of us because we blundered. All we have to do is own up to it and get straightened out before a mistake becomes a way of life.

I think religion is important, too. Very important. The turning point in my life came when I was nineteen. I was in prison. The authorities of the prison decided to move me; I was a potential troublemaker.

Before I was transferred, the prison chaplain, Father Kanaly, asked me to promise that I’d be a good boy, wherever I went. By then Father Kanaly had won my respect, simply by treating me as a person, a human being. I made that promise—and I kept it.

But I was bitter and despondent, because I hadn’t been baptized. It was another part of that hunger to belong to the human race. Father Kanaly understood. He followed me to the Union Depot in Oklahoma City and asked me if I still wanted to be baptized. When I said I did, he baptized me then and there, solemnly and quietly—in the men’s room of the railroad station!

As a child, I’d heard about religion and had gone to church and Sunday school occasionally. But I was bored by Sunday school. Such teaching does a great deal of good for some children, but others, like myself, must be reached by a different kind of appeal. I feel that religion should start at home. It’s certainly true that parents can live a better sermon than they or anyone else can preach.

I also feel that young people should learn to earn money, even at home. Someday, they’ll have to go out and fend for themselves. If a youngster has had too sheltered a life, he may be afraid to go out and earn his own living. Even though I came from a poor home, I wasn’t given the incentive to work and earn money for the things I wanted to have and do, so I began to take.

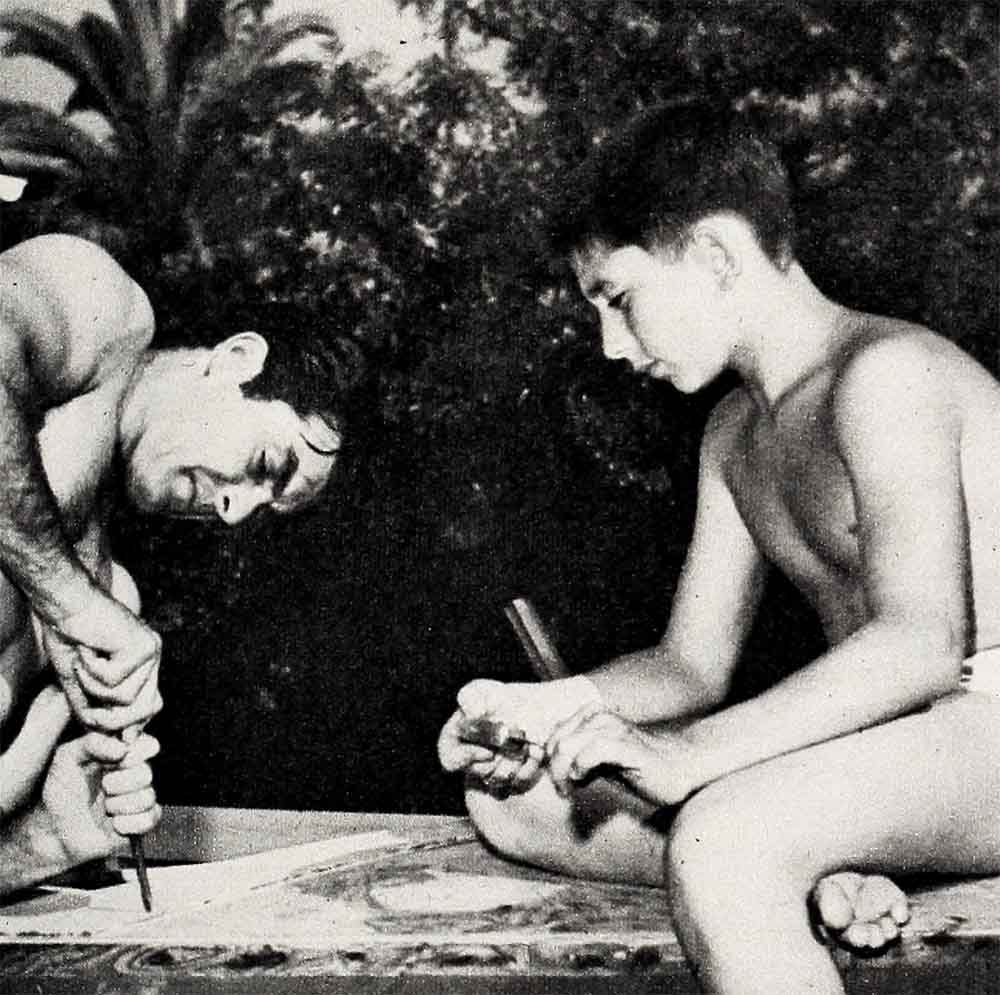

We can all lose money, but we keep our abilities, and they improve with practice. When I have children, I expect to give them a little money for each chore they do, such as cutting the lawn. If they get money by earning it, I don’t think they’ll ever be tempted to steal.

The mere fact that their parents are wealthy doesn’t keep children from getting into a jam. Wealthy parents who pay too little attention to what their kids do are just as bad for them as poor parents who can’t find time to answer their questions. In some wealthy homes that I’ve been in, the children have no one to talk to except maids or nurses.

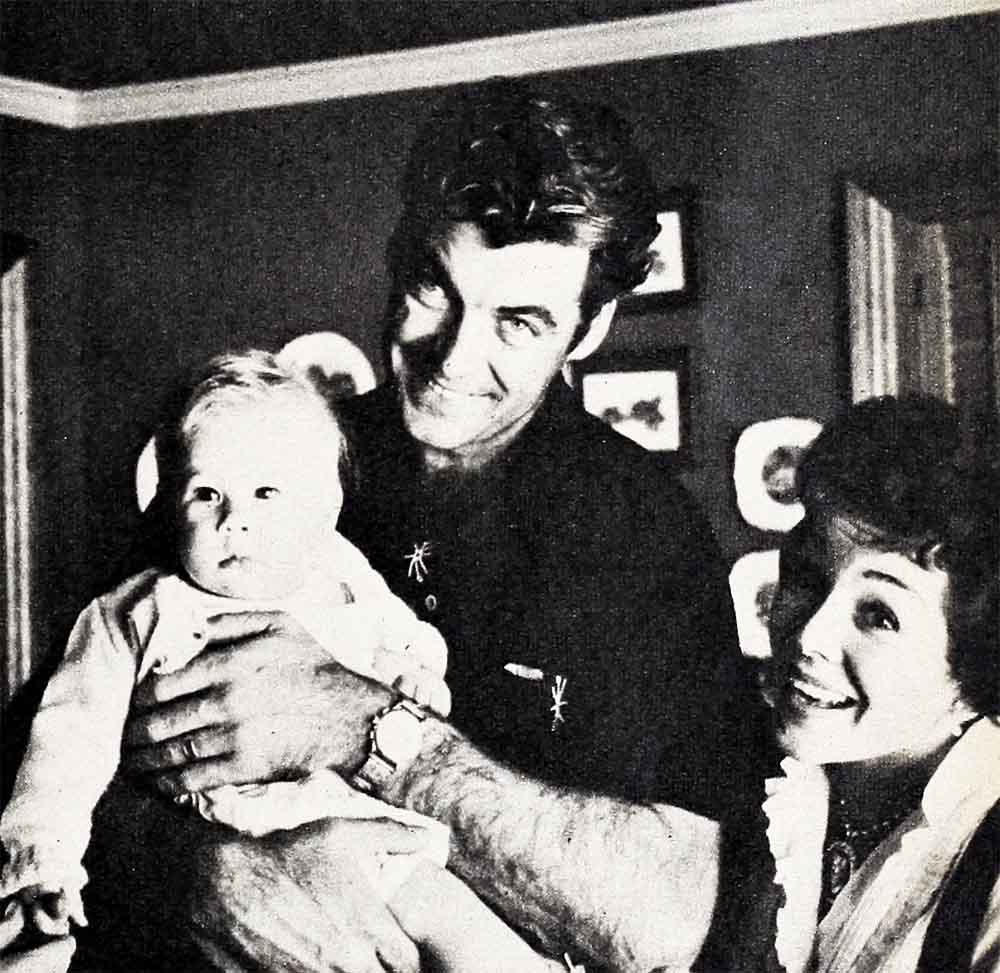

That’s one thing I wouldn’t want for my children. Lita and I won’t leave the entire upbringing of our children to a nurse or a maid. We’ll be thankful for the privilege of raising kids.

Lita has been pregnant twice, and has miscarried twice. But I have great faith in God’s wisdom, and I hope and believe that this time her pregnancy will reward us with a little son or daughter. Of course, whatever happens is in God’s hands and, when we say our prayers, we always add, “Thy will be done.” We know that if it is right for us to have children, He will send them to us. Then it is up to us to give them the kind of life that will help them develop into people we can be proud of.

The late, great Father Flanagan, of Boys’ Town, once said, “There never was a bad boy.” Children aren’t born wanting to be bad. Sometimes they become that way through too much discipline, sometimes from too little. But mostly they get that way because, somewhere along the line, they’ve been given the feeling, the idea, that nobody wants them, that they’re not important. So they become important by joining gangs, by stealing, by forcing people to notice them.

I know a man who never disciplined his son. The boy was all he had and he was afraid of losing his love. The boy became more and more unruly until finally the father, exasperated, seized the child and whacked him. He thought his son would hate him for what he’d done. Instead, the boy came up to him several days later to say, “I thought you weren’t like other fathers—that you didn’t care what I did. I was glad when you spanked me the other night. I knew I’d misbehaved, but I thought it made no difference to you.”

There are all sorts of reasons why kids get into trouble. But the best thing that can happen to them is to find out, early in life, that nobody ever really gets away with anything. The smart people “pay up” while their debt is small. They admit, to someone, that they owe a debt to society, and they set about paying it off the same way they’d pay any other debt. But the stupid ones let the debt ride and grow, until the only way to pay it off is to go into a kind of personal bankruptcy that they’ll pay for life—or with their life.

And what’s smart about something like that, hmmm?

THE END

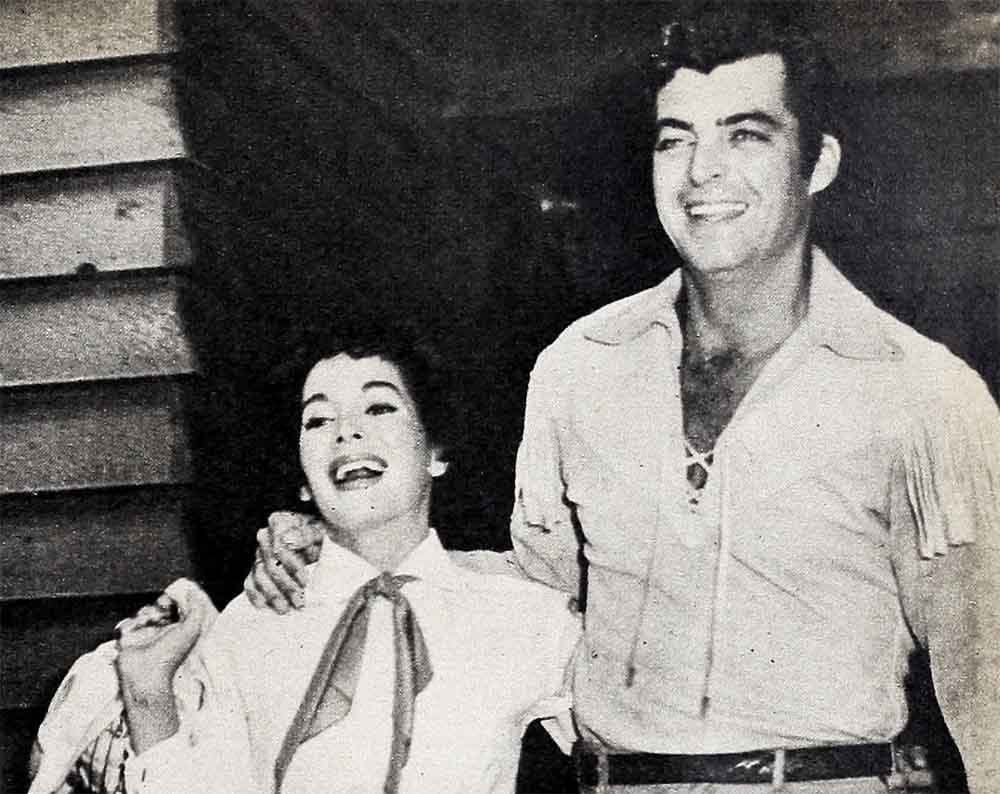

BE SURE TO SEE: Rory Calhoun in Columbia’s “Utah Blaine.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1957

AUDIO BOOK