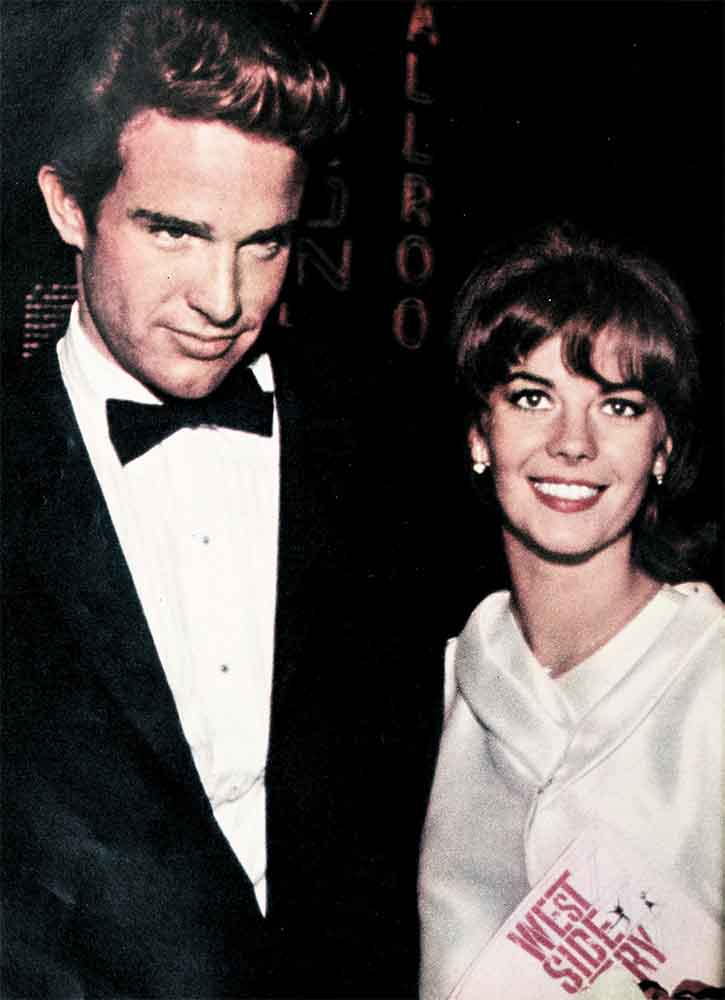

Wedding Bells For Natalie Wood

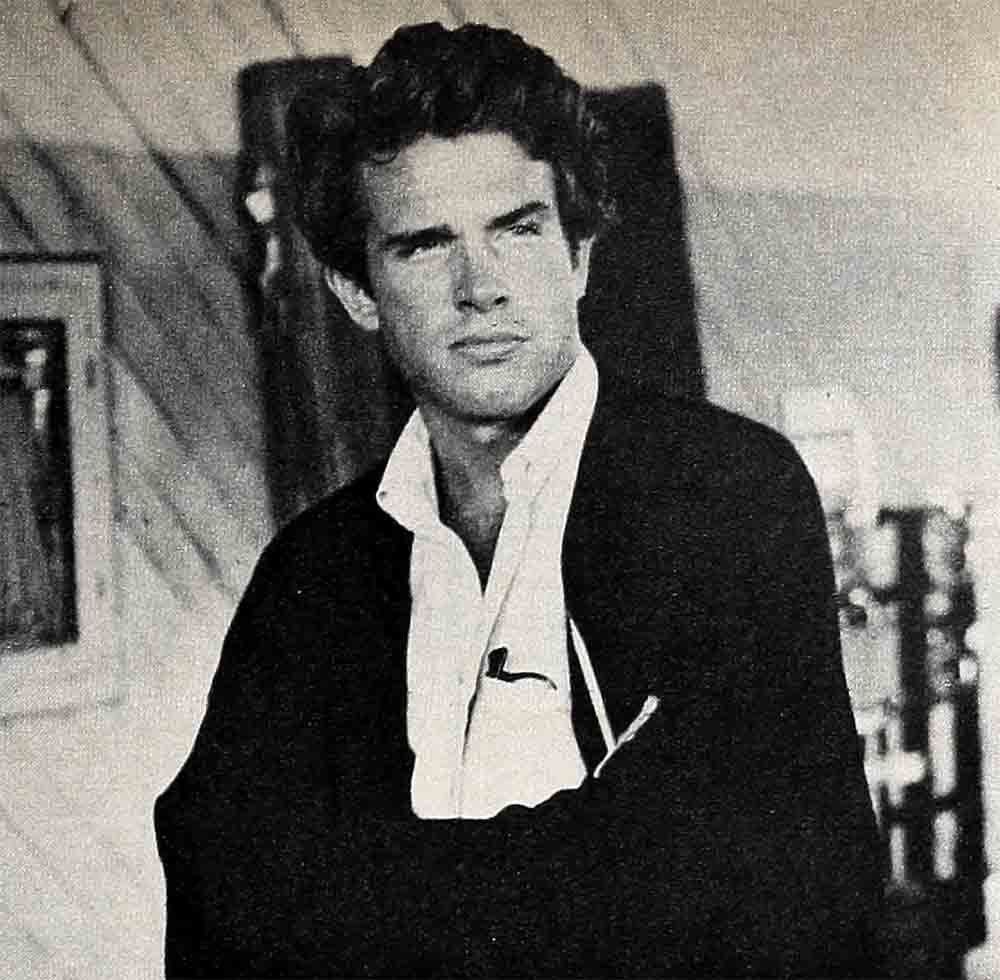

The boy and girl are in close embrace. They are pressed together in the front seat of a car. Past the boy’s head and shirt-sleeved back, the girl’s face is visible. Her dark eyes are large and moist. Second by second, the expressions in them change. Fear. Desire. Fright. Pleasure… Her eyes change, but her lips don’t. They are full, sensuous, slightly parted. The lips of a woman, the eyes of a girl… Suddenly she speaks. Her words aren’t as significant as her gestures. A drawing back out of his arms. A smoothing Of the Skirt Of her Summer dress. A putting on of her jacket. A shrinking into herself… The boy tums and his face comes into view. He is as handsome as she is beautiful. Brown shock of hair. Blue-green eyes. But now his eyes are disturbed, brooding. Anger shows in them—and tenderness—and frustration. He starts the car. Drives her home.

The boy? He is Warren Beatty. And the girl is Natalie Wood. This intimate scene is from a motion picture, t he opening of “Splendor in the Grass.” It’s a scene on celluloid, dreamed up by a writer, acted out in front of a camera by performers under the guidance of a director, and finally projected on the screen of a theater. A scene about sex, a picture about the problems and pressures of being young and in love. A screenplay about the Central questions of youth: Who am I? What am I? Where am I going? What should I do?

A scene on the screen . . . But something else, too. What takes place on the screen during the first scene of “Splendor in the Grass” throws a revealing light on the real-life problems of Natalie Wood, and on the dilemma confronting Warren and Natalie. For as Natalie and Warren play out their drama of love and frustration on the screen, one thing is immediately obvious: the magnetic electricity that this boy and girl generate when they’re together. This has a lot to do with Warren’s tough-tender animalism, a smoldering sexiness which led Eva Marie Saint to say about him, “Some guys come at you like a Mack truck. This one is slow, smooth and in complete control.” It also has a lot to do with a provocative confusion that comes out in Natalie’s every word and gesture, a conflict between the whisperings of her conscience, “This is what I ought to do,” and the urgings of her heart. “This is what I want to do.” It is this same on-screen magnetic electricity that has drawn them together off-screen, too.

It is life imitating art.

In fact, the romance rumors linking Natalie and Warren started while they were actually making “Splendor in the Grass,” while she was still married to Bob Wagner (and were vigorously denied by all parties concerned). These rumors were revived after Natalie and Bob separated. and became undeniable when she flew down to Florida to be with Warren while he was making a movie there.

But it was in New York that the on-screen sparks they’d made together ignited into an off-screen blaze that flamed like a prairie fire across Manhattan.

Warren was waiting for Natalie when she stepped off the West Coast plane at Idlewild

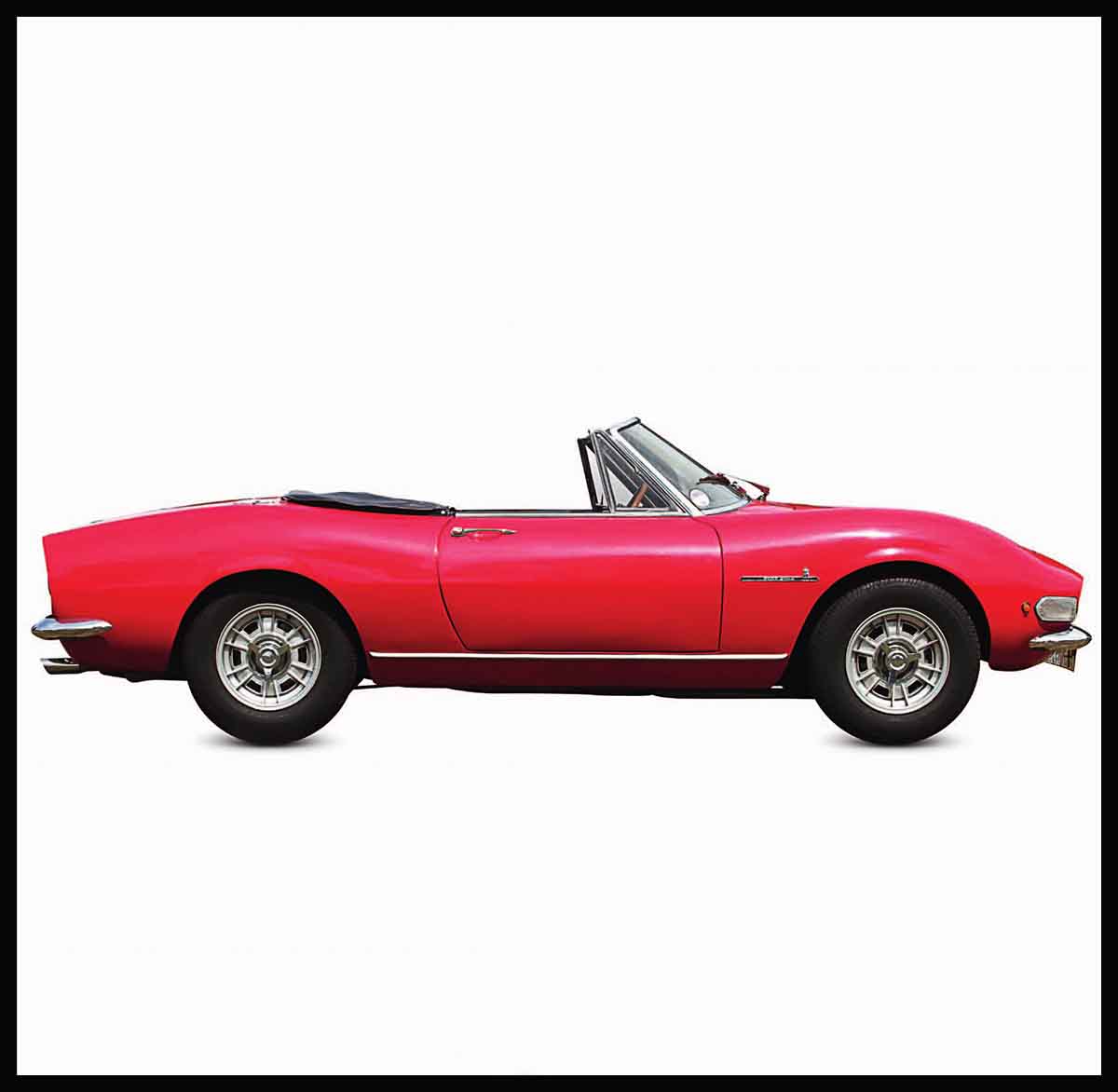

Airport. As she approached the black Thunderbird in which he was sitting. he slid his six-foot-one-inch, 175-pound frame out from under the steering wheel and rushed forward to meet her. He shoved his heavy-rimmed glasses into his jacket pocket, grinned happily so that the usual heavy, brooding expression of his full lips was suddenly warm and boyish. He swept little Natalie up into his arms. She squealed in mock protest until he kissed her—and then she was very, very quiet.

She climbed into the front seat, he gunned the T-Bird, and away they went—to the Plaza Hotel. She registered (Warren already had his own room there on a different floor) at about 11:30 P.M.

Natalie and Warren were back together again. and within a few days all New York knew it. John David Griffin, the TV columnist for The New York Mirror, summed it up succinctly: “The way Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty carry on around Gotham, it’s a wonder they have time to eat.”

Back in Hollywood, at a party tossed by Cyd Charisse and Tony Martin, they’d danced so “intimately”—to quote a goggle-eyed onlooker—that by the next day all Hollywood realized they were more than “just friends.” Now in New York they danced a “mean Twist” at the Leoton Club, listened to music at the Eden Roc, held hands at the Harwyn Club, went to the premiere of “West Side Story” and popped up wherever there was excitement and romance.

Natalie gave interviews, of course. After all, the official reason they were both able to take this three-week fling in New York was that they were publicizing “Splendor in the Grass.” But as she fenced with reporters, avoiding all questions about her relationship with her leading man, Warren was always close by, pacing up and down outside in the hail, coming into the room suddenly and leaving just as suddenly, twiddling his thumbs impatiently downstairs in the lobby.

Once he was seen roaming the corridors of the hotel, his shirttails hanging out sloppily in the approved Hollywood style. A man stopped him and asked, “Why are you dressed like that?”

Warren’s blue-green eyes narrowed to icy slits and he snapped back, “What’s it to you?”

“I’m the house detective,” the man answered, and for the first time in his life Warren backed down.

In “Splendor in the Grass” Bud (Warren) and Deanie (Natalie) are in love, but are doomed never to have each other; in their three-week idyll in New York, Natalie and Warren rewrote the script and improvised as they went along.

Is it really love? With intense, dynamic youngsters like Warren and Natalie, no one can tell for sure. But one evening, as she sat in the lounge of her suite in the Plaza, Natalie almost revealed herself. “Love is the most important thing there is in life,” she said. “I don’t see how people can enjoy life or even exist without love. I know I can’t.”

A few more words, and then she caught herself. She asked to be excused and left—for a date with Warren.

Near the end of their stay in the city, they escaped from nosey reporters and snooping house detectives by borrowing composer Jule Styne’s apartment. But still the columns were filled with items about them: “Warren Beatty gave Natalie Wood a Chihuahua pup”; “Warren B. and Natalie W. are so in love it hurts—hurts everyone to watch them, that is, who isn’t young. and beautiful and as full of excitement as they are”; “When Natalie Wood (Wagner) and Warren Beatty fly west again. they may skip L.A. altogether and go straight to Mexico, where she can get a quick divorce from husband Bob and become Mrs. Beatty.”

Life imitating art. Except—frustrated lovers on-screen, fulfilled lovers off-screen. Writing a new page of their real-life script day by day. Unsure what their final scene will be like, uncertain if their drama will have a happy ending.

But “Splendor in the Grass” does more than illustrate the magnetic electricity that Natalie and Warren generate. It also dramatizes the baffling difficulties which face young people—problems of sex, problems of morality, problems of love: difficulties, in short, which have plagued Natalie Wood for years. The questions that confuse and confound her now are the same questions that have puzzled her since she was a little girl: Who am I? What am I? Where am I going? What should I do?

As a child star, Natalie was an immature youngster thrust into an adult world. At six she told an interviewer (and her words carried a conviction and a seriousness that just couldn’t be laughed off), “I don’t like girls much. But I do like boys.” At seventeen she told the same reporter, “I still don’t like girls much. But I still like boys.”

What she had said at six, in all innocence, she was able to say at seventeen from more experience than some women have in a lifetime.

At twelve she received her first present from a boy, a watch and ring. They were lovely, but she couldn’t figure out why the boy didn’t call her after he sent the gift. One day she got her answer by mail. He sent her a letter from a reformatory explaining that he’d been arrested for robbing a jewelry store.

At fourteen she went out on her first grown-up, unchaperoned date. The boy was much older, nineteen or twenty, a premed student. Already she knew how to twist a fellow around her fingers. She recalled later, “We went down the Street for a Coke, and he let me drive his car”—even though she didn’t have a driver’s license.

At fifteen she was going steady. But one boy couldn’t be as interesting as many boys, so she broke off with him. She received a call from his folks. When he’d heard that they were through, he shot himself. Just a superficial flesh wound, true, but she was discovering her own powerful—and dangerous—effect on the opposite sex.

By the time she was seventeen and declared “I still like boys,” she was dating six or seven nights a week. Boys and men. Nicks Adams, Raymond Burr, Dennis Hopper, Tab Hunter, Perry Lopez, Scott Marlow, Martin Milner, Elvis Presley, James Stroman and Bob Vaughn.

While other girls were going to high-school dances, she was already bored with night clubs. While other girls were trying to talk their parents into letting them have boys drive them to and from parties (“Honestly, Mom, he’s a good driver and never speeds and I’ll be home by twelve!”), she was speeding around town in her own car.

When asked what she considered a good time on a date, she answered, “Anything spontaneous”—and she meant it.

On her eighteenth birthday, for example, she planned a party. “I was just going to have all boys,” she said later, “but I changed my mind.”

That was the year she jumped fully clothed into a swimming pool while Marlon Brando watched in amazement.

That was the year she sat behind Elvis on his motorcycle while he barreled down the Street. Later, she threw convention to the wind when she visited him at his Memphis home.

That was the year she went wild—anything for “kicks”—until one day she met Bob Wagner.

That’s why she didn’t have just boys at her birthday party—because of Bob. She celebrated it with him instead. He took her to the premiere of his picture, “The Mountain,” which meant a lot to him.

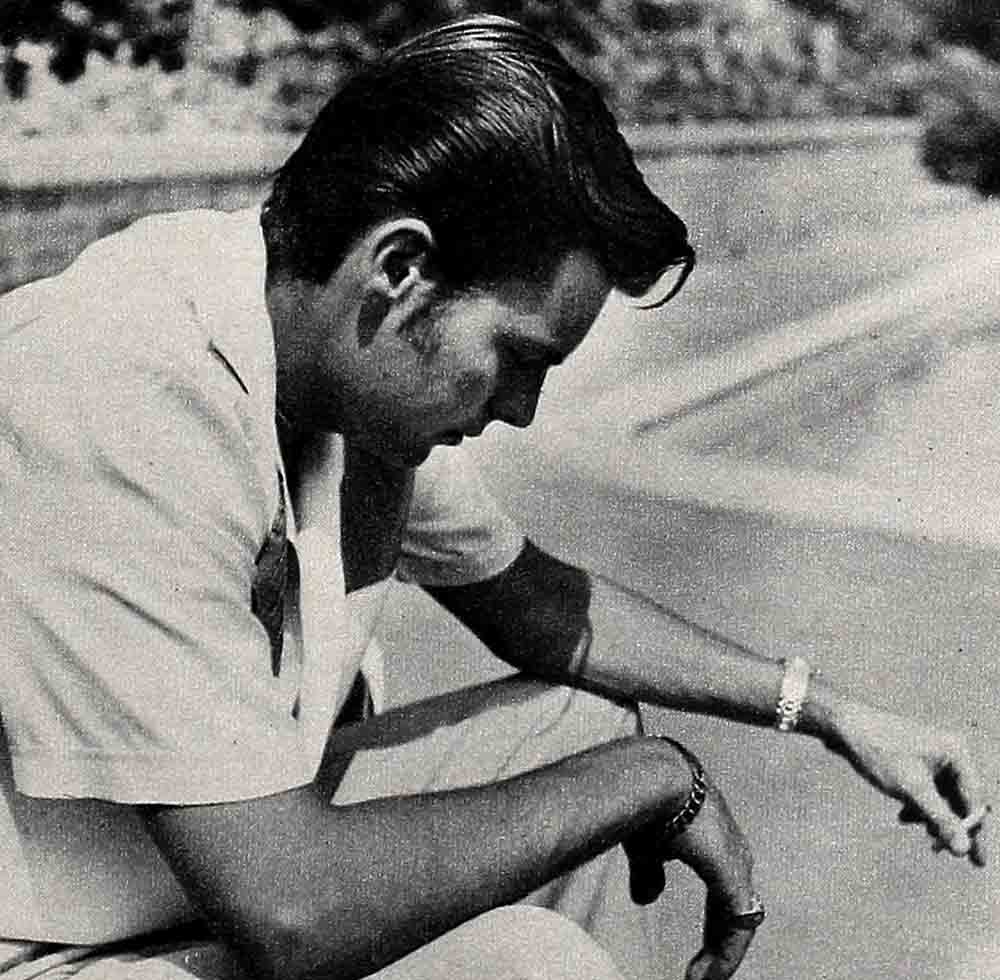

Bob Wagner was the last man anyone in Hollywood thought she’d fail for. He was too calm and considerate and nice. A gentleman. The perfect boy-next-door.

Not that he wasn’t handsome; he was, with a kind of brown-haired, blue-eyed All-American-boy good looks. And he was attractive to women. After all, he’d almost married Debbie Reynolds (before Eddie came into the picture), and at one time or another he’d been linked with Terry Moore, Jean Peters and Barbara Stanwyck. Bul he just didn’t seem strong enough for someone like Natalie.

She was flighty, changeable, a creature of whims and fancies. As she herself admitted, “I’m a real moody one. Sometimes I feel so low I want to die. Other times, I’m so happy I want to fly. And all for no apparent reason.”

In a moment of extreme honesty, she once prescribed for herself the type of man she needed. Either someone who would fly with her one moment and die with her the next; or someone firm and unyielding: “It makes me feel protected to be with a fellow who bosses me.”

Not a fellow who was even-tempered, calm and understanding like Bob Wagner. Someone dynamic, mercurial, forceful. In short—Jimmy Dean.

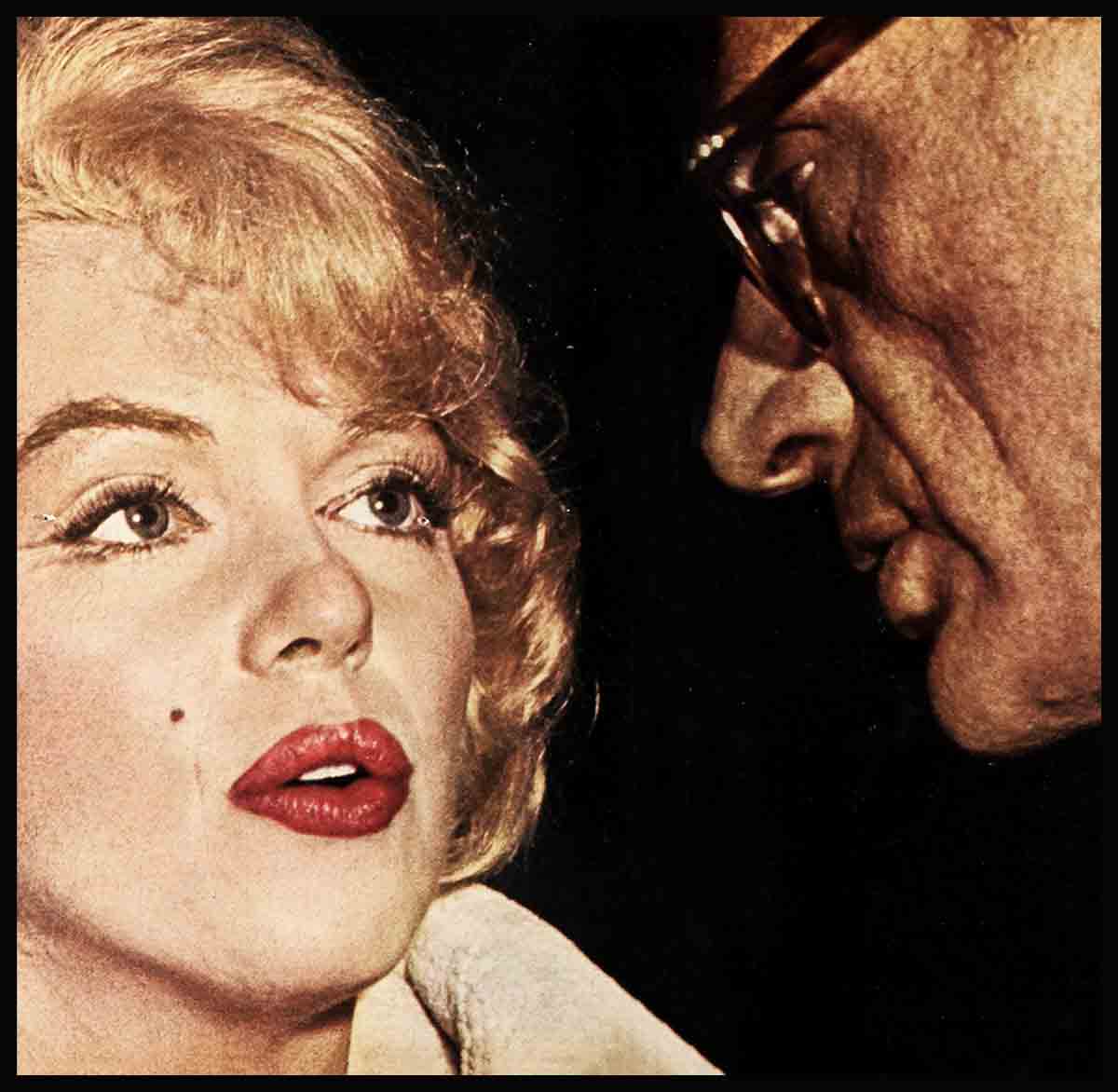

She made “Rebel Without a Cause” with Jimmy. And she gave off sparks—on and off the screen. (It was to happen like that only once more—years later—when she met Warren and made “Splendor” with him.) One special afternoon with Jimmy she later termed “the happiest day” of her life. “It was when we did our love scene in the deserted house,” she recalled. “It seemed to me that everything I’d ever dreamed up for myself was taking place at that moment.” (And it is ironic that Bob Wagner once said of “Rebel” that it “seemed pointless and meaningless.”)

But with Jimmy’s death, Natalie’s dream changed into a nightmare. “I can’t forget him,” she said. “Sometimes I wonder if I’ll always have this feeling.”

She continued to wear a love-bracelet around her ankle. “Jimmy Dean gave it to me,” she said. “I never take it off.” Jimmy Dean was dead, and with him a bit of Natalie Wood died. too. Perhaps she fell in love with Bob Wagner because he was so different from Jimmy, and because with the one she could forget the other. Perhaps . . .

After one year of “going together,” Natalie and Bob decided to get married. The news had a shattering effect on their friends. Love? Okay. But marriage—for Natalie? Unbelievable. She was married already—to her career.

Natalie herself had drummed this credo into their heads. Hers wasn’t the usual “they forced me to become a star story. Quite the opposite. She freely admitted, “I became a star not because my parents forced me into it out of their own frustrated desires, but because as a child I . . . wanted nothing more than to act.”

In everything she said and did. it was as if acting were the most important thing in her life. Boys were fun. Love was a luxury. But her career was a necessity. She said so herself, in a hundred ways:

“I think people have to decide whether they want to have a career or marriage.”

“All I’ve ever wanted to do is act.”

“I guess I’m one of those corny, dedicated actresses people make jokes about.”

“You might say I’m going steady with acting.”

Now suddenly she went back on everything she’d ever said. She didn’t believe marriage and a career could mix, yet on December 28. 1957, she upped and married Bob Wagner.

She’d declared that “my man, when be comes along. will not be too conventional.” But Bob had been so conventional—even old-fashioned—as to ask her father for her hand before be ever popped the question to her.

There was only one possible explanation. Love. Love that ignores logic.

“Forever”—three years

At the altar Natalie whispered to Bob. “Darling. this is forever.”

In a statement issued jointly to the press, Bob and Natalie declared, “Our marriage vows mean we love each other and that we are one forever.”

In an interview they both insisted, “Our marriage is more important to us than any career.”

Forever lasted thirty-six months. For three years. they shut themselves off from the rest of the world either in their house or on Bob’s boat. When they did venture out, it was always side by side.

But there were moments, even when both were insisting how marvelous their marriage was, that trouble peeked through. Once, in a statement to the press. Bob said. “It’s been wonderful from the moment I slipped that wedding ring on Nat’s finger.” But then he halted for a second and added, “But it isn’t true that we haven’t had some rough spots. Not between us, you understand—but during our first year of marriage Nat was having serious career trouble. . . . At that time when Natalie was out of work. I was working. Then there was a period when I had a long wait between pictures. There were moments when we were worried.”

Career trouble. And for actors—especially a dedicated actress like Natalie Wood—that’s bad trouble.

What was happening to Natalie was bad enough. “Marjorie Morningstar,” a box office flop for all the hullabaloo; mediocre roles in “Cash McCall” and “Kings Go Forth.” A string of artistic and financial failures. But what was happening to Bob was worse. He’d always been hailed as a “rising young star.” Suddenly, at thirty-one, he was no longer so young and definitely not rising.

He made a series of pictures that either nobody remembers or somebody wants to forget. The critics, when they took note of him at all, damned him with faint praise. One reviewer praised him with a faint damn when, in speaking of his performance in “Say One for Me,” he wrote, “It is not his fault he is miscast.”

Bob tried to bolster his sagging career by making a record. “So Young” was very poor; the flip side, “Almost 18,” was impossible.

In desperation—and despite all their insistence that “we’ll never appear in a picture together”—Bob and Natalie costarred in “All the Fine Young Cannibals.” The critics devoured them alive.

Then overnight, everything changed.

The modest-living Wagners bought a $150,000 home, began to decorate it in a Graeco-Roman style, and poured $50,000 into furnishing just one bedroom and bathroom.

Natalie made two big ones in a row, “Splendor in the Grass” and “West Side Story,” and the word went out, even before the film was dry on both pictures, that either of them might win her an Academy Award.

Once, someone had asked Bob how he’d feel if Natalie’s career skyrocketed to where he’d be known as “Mr. Wood.” His reply was, “It wouldn’t bother me at all. In fact, I’d regard it as a compliment.” But now that the supposition had become a fact, there was tension and trouble in the Wagner mansion. And it couldn’t be smoothed over by statements to the press. On the contrary, after “Splendor in the Grass” was released, Bob and Natalie announced that they had agreed to disagree. One columnist put her finger on the main reason for their separation when she wrote: “Close friends of Natalie Wood and Robert Wagner attribute their breakup to the most familiar of Hollywood troubles, career jealousy. Natalie’s career is zooming. ‘R.J.’ isn’t doing quite that well. . . .”

An end and a beginning

The end of a marriage. The blackness of despair and defeat.

And suddenly the miracle of new love. A man holds Natalie in his arms in front of the cameras and she feels alive again. as an actress and as a woman. A man holds her in his arms off-screen and once more she believes in love.

In the broadest sense, the problem on the screen becomes the problem in her life—the problem of youth and love.

Who am I?

Am I a girl who has grown up at last? Do I finally know my own heart?

What am I?

Am I first a woman and then an actress? Or first an actress and then a woman?

Where am I going?

Shall I trust myself and my future to this new man—a man with the eyes of a boy and the passionate mouth of someone who has been alive since the beginning of time? . . . So like Jimmy, yet so different. The same tender forcefulness, the same crazy disregard for convention. But different, too. A man who can be “engaged to be engaged” to a woman, Joan Collins, for two years—and then suddenly turn off his heart in one second.

What should I do?

Say “Yes” to him if he asks me to marry him? open myself up to possible rejection, disillusionment and unbearable pain?

These are the questions Natalie Wood must be asking herself today as she weighs her future with Warren Beatty or without Warren Beatty.

The door to her marriage to Bob Wagner has slammed closed behind them—there is no turning back. Bob, after dating Warren’s ex-girlfriend, Joan Collins, and also Linda Christian, now wants to marry Marian Marshall, Stanley Donen’s former wife. Marian and her children live in Italy, so Bob has declared, “I will settle in Rome—I think it’s the greatest.”

As for Natalie, one thing is certain: she will face her problem head-on. “I give myself credit for only one thing,” she says, “and that is complete honesty with myself. I may do something wrong from time to time, but I don’t pretend it isn’t so.”

But—the old dilemma is still there: career or love for the girl who is every inch an actress and a woman.

One moment, thinking of Warren, she is able to say, “I won’t say I’ll never marry again—but I will say it won’t be for some time.”

The next moment, in answer to the question. “How would you feel if you were nominated and won an Oscar?” she replies, “It would be the most exciting moment of my life. I’d rather carry home one of those ‘boys’ than any other kind of boy!”

In its turbulence, uncertainty and confusion, life, Natalie Wood’s life, imitates art—the sad, lost, searching, lonely role she plays on the screen.

—JIM HOFFMAN

Natalie stars in “West Side Story,” U.A., and Warners’ “Gypsy.” Warren is seen in “The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone.” Warners, and “All Fall Down,” M-G-M. Bob is in “Sail a Crooked Ship,” Columbia.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1962

No Comments