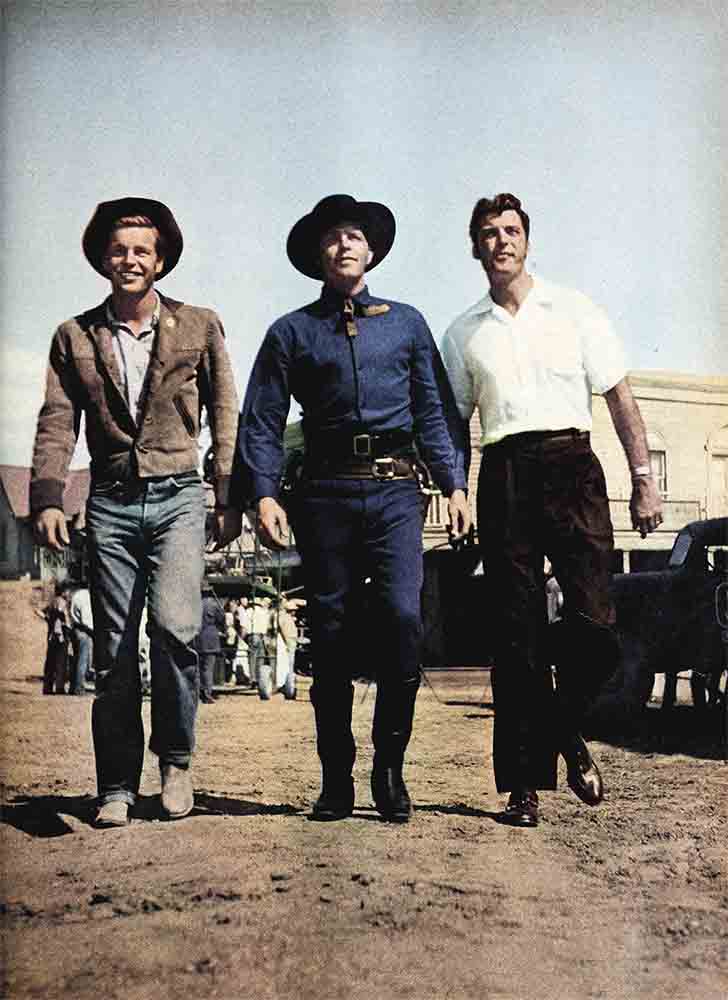

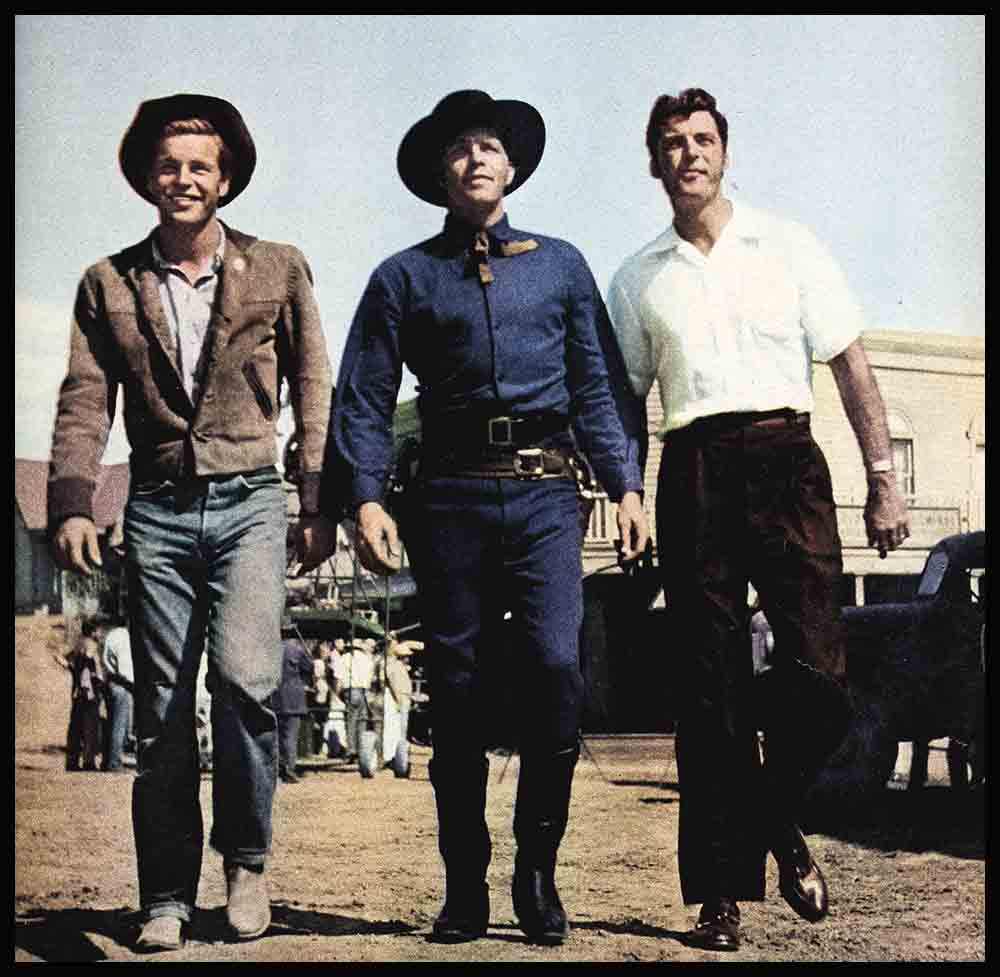

Terrific Trio

When “The Silver Whip” was cast, there were a few uneasy heads at Twentieth Century-Fox, for the leading roles were to be played by Dale Robertson, Rory Calhoun and R. J. Wagner. “They’re in competition whether they like it or not,” said a studio spokesman. “They’re our three top leading men, and they’d have to be pretty dumb not to know it. Nobody will be a bit surprised if there are some hot tempers popping off while this picture is in production.”

The terrific trio was full of surprises, all right—but none of them had anything to do with temperament. Dale and Rory have been friends for years, and for all those years, they’ve been needling each other. If Rory is making a Western, Dale saunters uninvited onto the set to say, “I know you won’t mind, Ror’, but I’m riding for you in the next scene—the director wants a manly type to take over.” Or Rory will visit the set where Dale is studying his script, whack the startled Robertson on the shoulder, and shout reassuringly, “Relax, old buddy! I’m going to do that tough bit for you—the one where you’re supposed to speak English.” The day that this badinage doesn’t take place, somebody’s feelings will be really hurt.

It was young R. J. Wagner who bore the greatest brunt of the hazing while “The Silver Whip” was in production. Bob had learned about working with Rory in “With a Song in My Heart.” At first, he was so wary of the practical joke that he refused to track down a perfectly legitimate item called a left-footed spur. His caution got him nowhere. He remained a boy among men, a city slicker handicapped by the unfamiliar six-guns, Stetson and cattleman’s boots which his senior co-stars wore with grace and ease. Between scenes he was never permitted to ease his tired frame into a chair; Rory and Dale ordered him to “hunker down,” or, squat on his haunches, as cowboys do around a campfire. Having learned to balance thus precariously on his high-heeled boots, Bob was given a clasp knife and a piece of wood and instructed to whittle. Just whittle. Cowhands relaxing never carve anything in particular, he learned; they just whittle until the shavings curl thick about their boots and the stick has become a sliver. Then they find another stick.

Under the guise of ribbing, Dale and Rory were giving him the benefit of their experience, teaching him the things he needed to know to lend realism to his role, and Bob was sensitive enough to understand that. But he was still boyish enough to be mortified when he swung aboard his old cayuse with what he hoped was a practised air, only to hear Rory break up the set by drawling, “Get a load of that tenderfoot—he’s looking for a gear shift on his saddle to make that horse go.”

He defended himself—or, at least, he made a manful attempt. “Maybe I’m new to Westerns,” R. J. boasted, “but I’m still the only guy in the picture who gets to kiss the girl!”

“That’s because you’re new,” retorted Dale. “When you get to be a star, you can have it written into your contract that you only kiss your horse. Anybody but a greenhorn like you would know that you’re never, but never supposed to kiss girls in Westerns!”

In the course of the picture, Wagner became so impressed that he bought himself an MG “because Rory and Dale drive MG’s.” It was worth a trip to the lot to see the three tall, handsome “Westerners” stride off the set, spurs ajingle, jackknife their lanky bodies into the perky little British roadsters.

They are all tall, handsome stars under contract to the same studio. But there the resemblance ends.

Dale Robertson is a very positive personality. He is always the most relaxed person on the set. He arrives at the studio well prepared for the day’s shooting; he knows exactly what he is to do, and he has made up his mind how he will do it. A “one-way” guy, Dale is stubborn. The studio executives are eager to groom him for the top stardom which is obviously his destiny, but they are limited in picture material by his refusal to lose his Oklahoma accent. “You just can’t put a guy with an accent like that in a drawing room without shooting another reel to explain how he got there,” said a doleful but logical Robertson booster.

Dale Robertson’s positive nature is also reflected in his marriage. Hollywood second-guessers try to tell you that success has gone to Dale’s head, and that’s what’s wrong between Dale and his wife Jackie. But the real problem seems to be that Jackie has had difficulty conforming to her husband’s ideals—and that those ideals are iron-bound. She had had a career of her own when she met Dale; true, her parts in pictures had only been bits, but even a small place in the sun satisfied a need of her own. Jackie is an intelligent girl, a gregarious one who loves people and is very much stimulated by them. She needs to be with them, but to Dale’s mind, a wife’s place is in the home.

The pivot man of the tempestuous threesome is Rory Calhoun, who knew both Dale and Bob Wagner before they were in pictures. He is the easiest of the three. He is a clown on the set, and he originates most of the practical jokes and gags. He is the most likely to fluff a line, the least apt to worry when he does. “What is there to do besides laugh it off?” Rory asks with a shrug of his broad shoulders. “How many times can a man say he’s sorry?” Rory’s emotional security is there for the most casual observer to see. He and his wife, the petite and volatile Lita Baron, are anything but recluses. All you have to do is ask them, and they’ll appear at a benefit, and they enjoy an occasional party immensely. But few of their close friends belong to the Hollywood scene, and they join in no frenetic scavenger hunts for excitement outside their own lives. On his days off, you can usually find Rory caulking a boat in the back yard or working on some odd job like paneling a room in their new Beverly Hills home.

What’s the secret of their happy marriage? Lita puts it this way: “After four years we still enjoy waiting on each other. We discuss Rory’s new roles, plan things we want to do together. Maybe we’re naive, but we don’t think people get married to get away from each other.

“When we go to a big Hollywood party, which isn’t often, neither of us gets lost. If Rory sees me trapped in a corner by some bore, he drifts over and gets me out of it. And there was one party last year where a certain woman was after Rory all evening long. Wherever he went, there she was, retying his tie, smoothing his lapels, playing with his hair, and after a long time I could see that he was really getting annoyed. So I excused myself to the people I was talking with and went over to rescue him. If anybody said anything rude to her, I wanted it to be me—Rory can be so blunt.

“There has been a lot of talk about that party; people talking about my Latin temper and my feud with that female. Well, you have to expect situations like that when you marry a man as attractive as Rory; but he knows I’m never angry with him when they come up. We know how we feel. I just got furious with that woman for embarrassing him.”

The third member of the triumvirate, Bob Wagner, is by far the most serious and intense. Acting is the Holy Grail to which he is dedicated. He must explore every possible facet of a new role before he rests easily in his characterization. Bob’s appearance in “The Silver Whip” was not the result of whimsical casting—he constantly besets his studio with pleas for “a different kind of part,” moving eagerly from straight drama to Western to song-and-dance, growing steadily in stature and experience. When he is able to portray every conceivable type with conviction, there will be one critic still dissatisfied with his performance. That critic is R. J. Wagner, who is marked with the unrest of the perfectionist.

Hollywood interest has been piqued by R. J.’s preference for the company of persons older than himself. But this is merely a mirror of what he has been and must be. First and foremost, he is the only child of intelligent parents who treated him as another adult as soon as he was old enough to grasp the meaning of the compliment. More important—and oddly touching—Bob is as movie-struck as any fan in the world. He can talk old pictures till dawn, and he would rather spend an evening at the feet of one of his cinema heroes or heroines than go out with the most beautiful girl in town. Looking for Wagner at a party, you will probably find him in a corner with one of his boyhood gods, absorbed, unaware that there are other people in the room. He’s paying tribute, yes—but he’s also studying voice and expression and gesture. R. J. Wagner learns something from everyone he meets.

His pleasure in older people has precipitated a new development in Bob’s private life. Rumor whispers that he can no longer count on a date with his erstwhile girl, Debbie Reynolds, because she resents his attentions to a glamorous “older woman” named Barbara Stanwyck. It’s true that Bob and Barbara have been seen at Ciro’s and Mocambo, that R. J. haunts the drive-ins and juke joints less frequently. It is equally true, however, that Barbara Stanwyck has long been a Wagner idol and that he would naturally consider it a great privilege to be at her side. And Barbara would be less than human if she didn’t find the worship of so charming and talented a boy beguiling. Whether Bob is merely going through a phase of sophistication or has truly outgrown the bobby-sox forms of entertainment remains to be seen; at this time he is as changeable as any other twenty-two-year old.

He’s more than serious and intense and changeable, to hear Rory Calhoun tell it: “I remember once when I thought he was getting off on a wrong track that would do his career no good. Because the same thing happened to me in the beginning and because I’ve known R. J. such a long time, I thought it might be a good idea if I had a fatherly talk with him.

“So I said my little piece one day when we were alone, and after I finished he said, ‘I don’t think it’s any of your business, Smoky.’

“Well, he was sure right about that, and I told him so. A couple of months later he was back, asking me questions about the very things I had tried to tell him. It made me feel good about him. R. J.’s a proud kid, real proud. I hurt his pride by giving him advice in the first place, and he had to swallow a lot of that pride to come back and ask for it after what he said. But he did it—he’s that kind of guy.”

The terrific trio is a motley crew, each different in philosophy, in attitude, in his impact on the fans . . . but they have one vital thing in common; each is a triple threat at any box office in the land.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1953