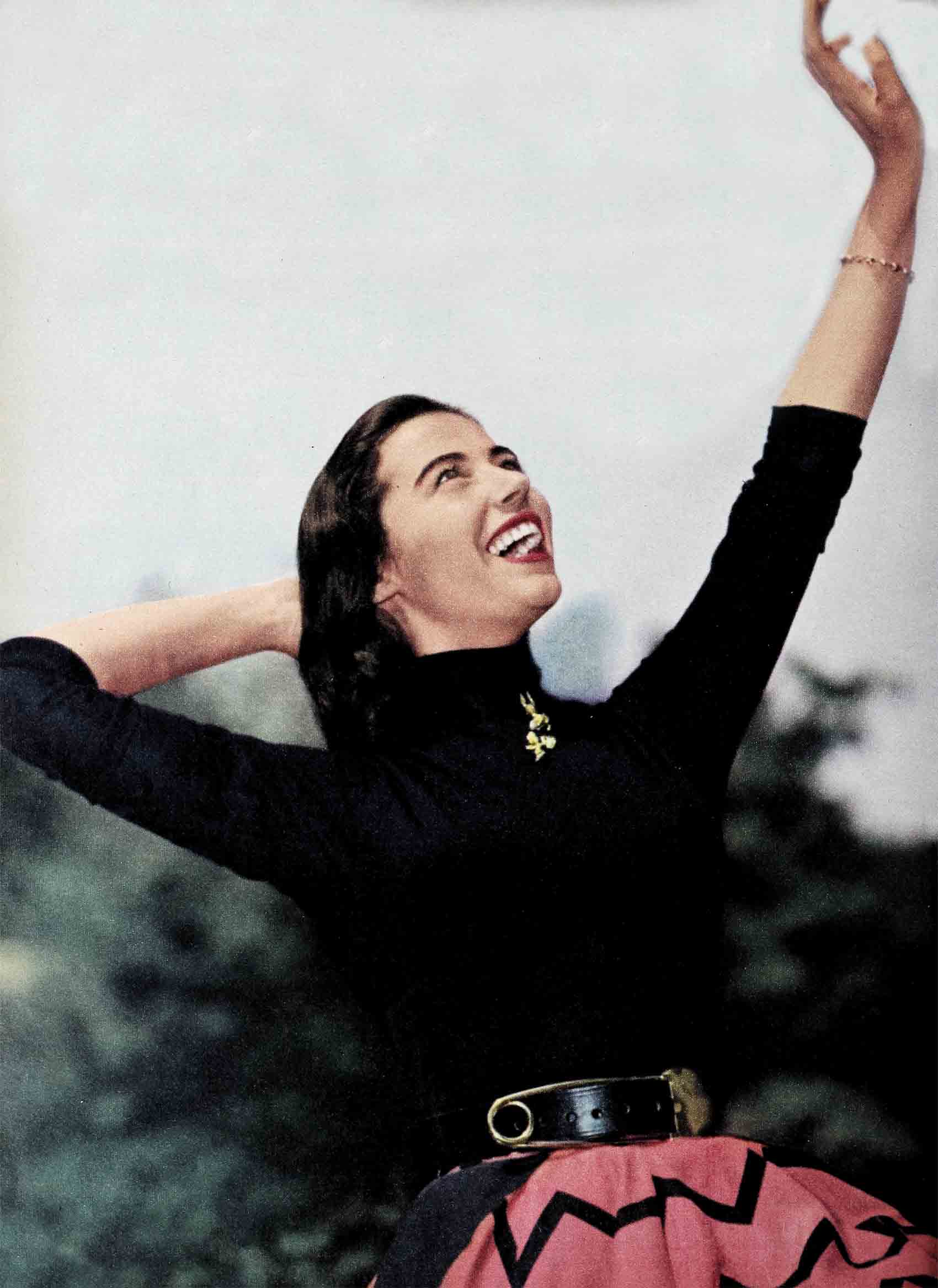

The Wonderful World Of Marisa Pavan

Italians are truly a remarkable people. After talking to them you suspect that they are born with a song on their lips and a talent for acting that is as natural as breathing. Imaginative and passionate, they instinctively recognize emotional situations and interpret them with an amazing delicacy of feeling. A wonderfully delightful case in point is shy and gifted Marisa Pavan, Academy Award nominee as the best supporting actress of 1955 for her role in “The Rose Tattoo.”

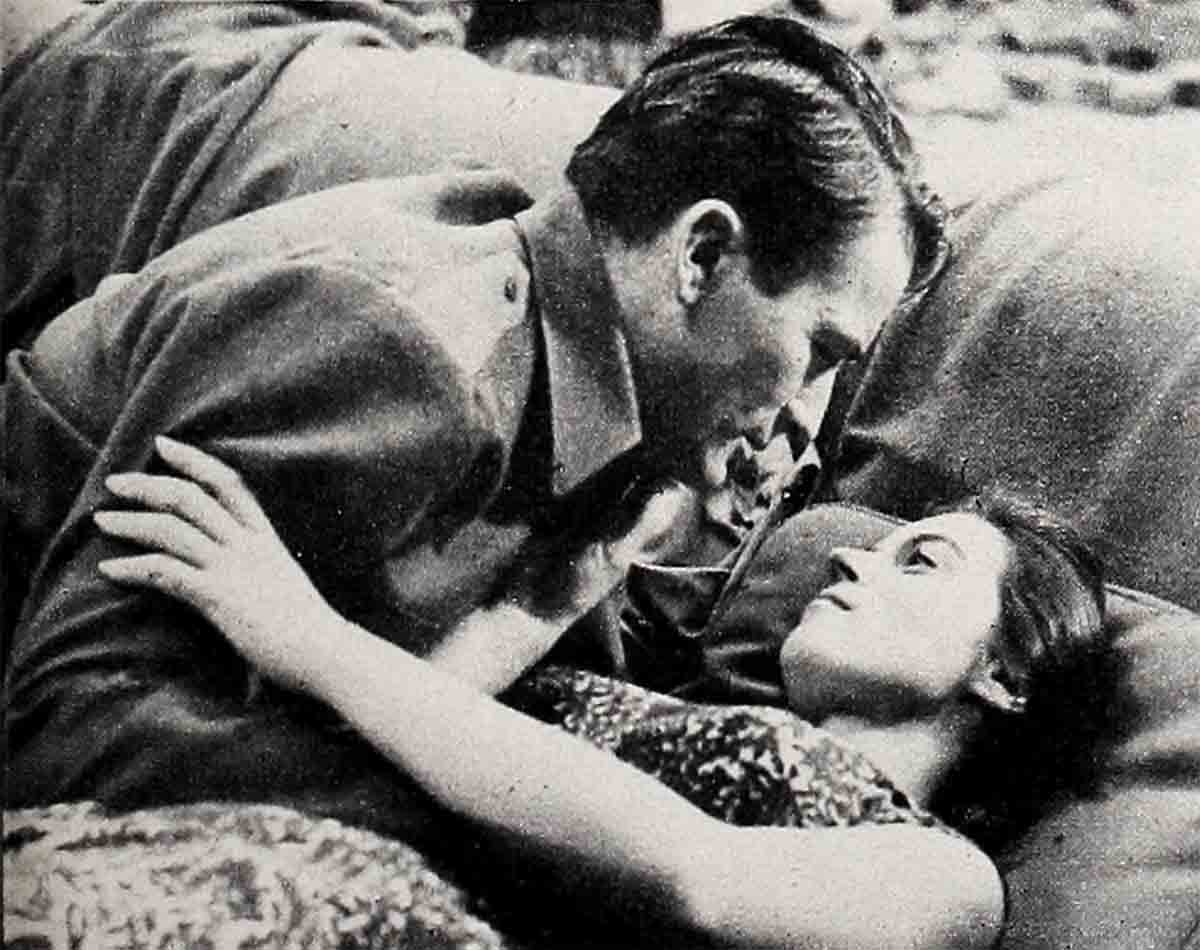

While making “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit” at 20th Century-Fox, Marisa was called upon to enact a tempestuous love scene with Gregory Peck. Greg, a seasoned performer who is noted for the conviction he displays in such situations, had his own idea as to how a girl should be kissed. This was entirely natural, for Greg has gone through this delectable rite ‘ many times on the screen, and always with polished aplomb. On this as occasion, however, famous writer-director Nunnally Johnson saw that the scene wasn’t coming off precisely as he’d envisioned it. After several takes, he said, “Let Marisa kiss you, Greg.”

The results were such that veteran crewmen, accustomed to displays of screen passion, tottered in their tracks, and a long, whispered “Ah-h-h” rose from the spectators. the There is no record that Peck’s famous savoir-faire was greatly disturbed—but his eyes were seen to blink rapidly.

Now comes the most interesting aspect of the episode—one which sheds a revealing light upon this sweet daughter of Italy. When asked about it, a deep, instantaneous flush mounted to the roots of Marisa’s dark hair and her brown eyes fell. “I do not wish to talk about that,” she murmured in an almost inaudible whisper. (Such modesty in Hollywood is almost impossible to find, and should be saluted with at least thirty seconds of silent respect.)

Mr. Nunnally Johnson, no man to strew roses before unworthy feet, was emphatic in his praise of Marisa’s acting, and in his approval of her outgoing personality. “Marisa has a fine talent,” he said. “I might go further and say she has a remarkable one. And, in addition to this, she has that priceless asset, a beautiful speaking voice. The first day on the set I observed that she did the correct things instinctively. She knew timing, the right, precisely right, intervals of pause.

“In her role, I wanted Marisa to portray a young Italian girl of the town—not a street girl, mind you—but one who had to compromise with life because she and those dependent upon her were hungry. How that girl played it! Like an old pro. You could feel hunger coming out of her with every line she spoke, every gesture she made.

“Marisa has about the loveliest eyes I ever saw. One day, I showed her a pair of cufflinks my wife had given me. They were extraordinary because they showed a woman’s eyes, set in enamel and gold. ‘I’ve had your eyes copied,’ I told Marisa. Of course, she is enormously shy, but I think she liked the compliment.”

Speaking of her work with Gregory Peck in “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,” Marisa said, “I used to see Greg in movies when I was growing up in Italy, and he was always my ideal. I would imagine the most exquisite pleasure that would be mine if I were an actress and had an opportunity to play in a scene with him. Of course, it was only a dream, and like most wonderful things we dream idly about, not likely to come true. And then, one day on the set of ‘The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,’ I suddenly remembered my dream and gasped to myself: ‘Dreams do come true. Oh, they do! They do!’

“Now that has become my philosophy,” Marisa continued. “I firmly believe that if one wants something hard enough and does something about it, almost inevitably that dream will be realized. It is the sad, wistful dreams without action that break the heart.”

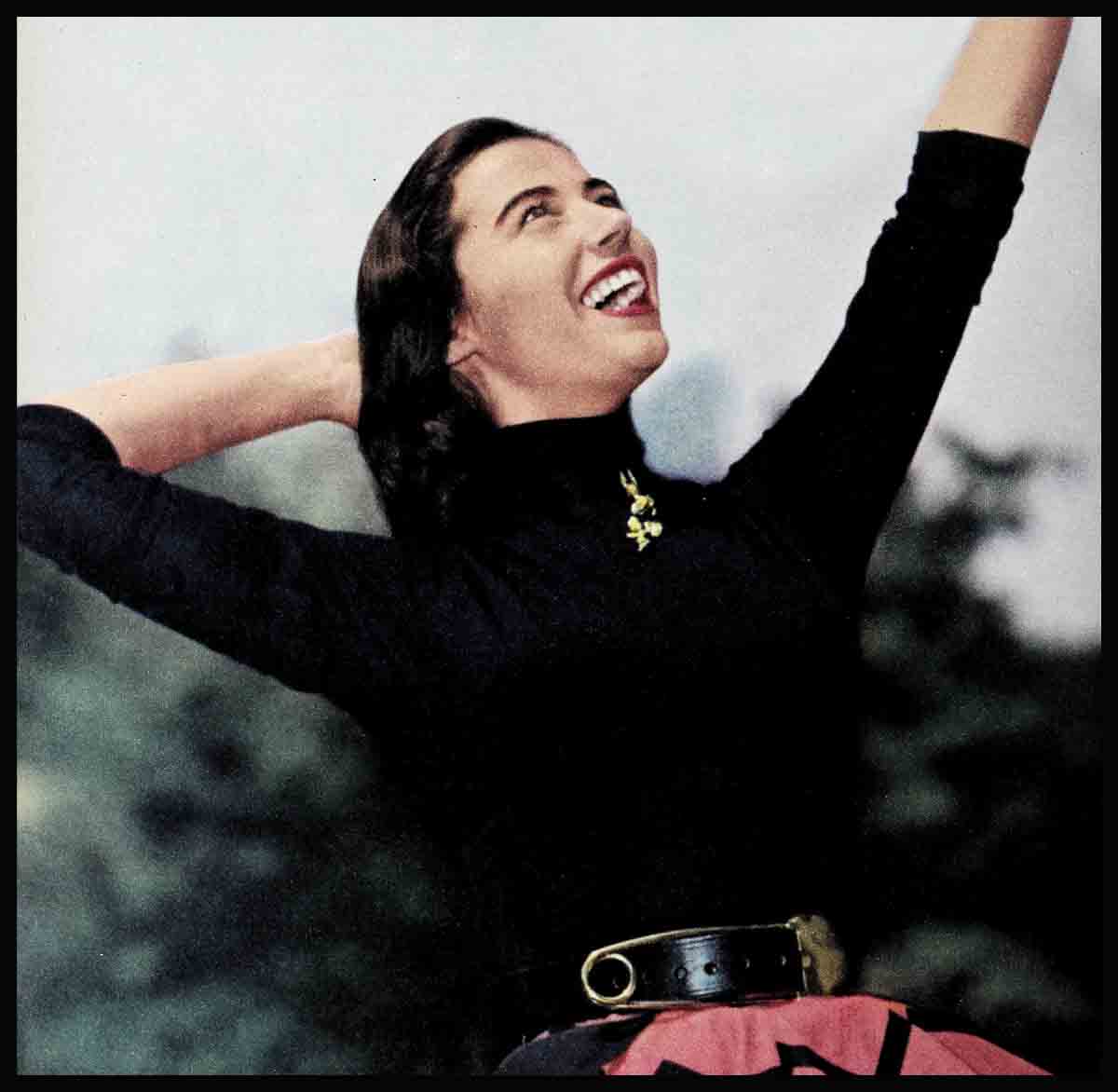

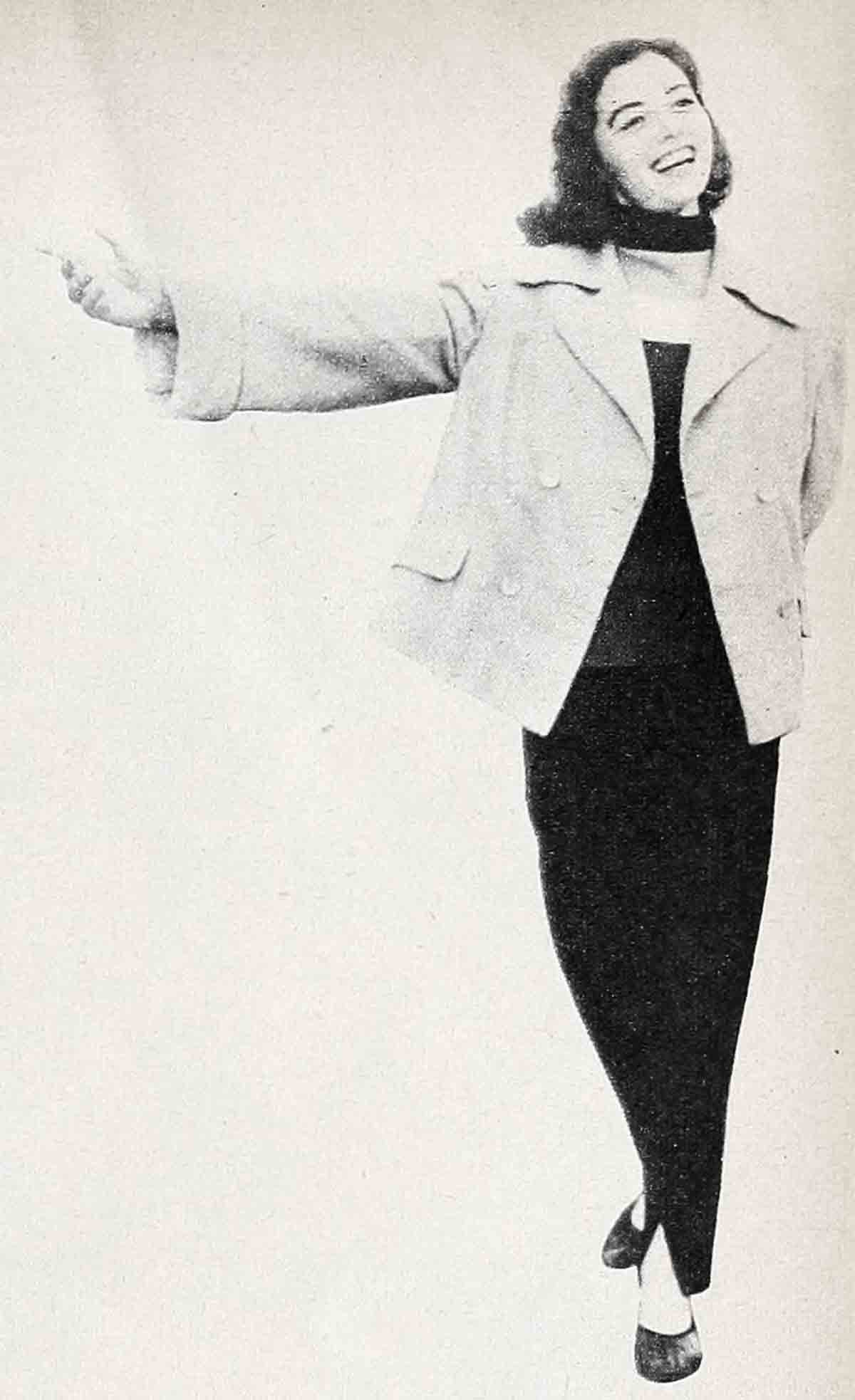

In a community where physical loveliness is almost taken for granted, Marisa Pavan presents a refreshing variance from this casual attitude. Not alluring by the standards which titillate young and old whenever Marilyn Monroe’s blond beauty is flashed upon the screen, there is something in Marisa’s olive-skinned, small triangular face—a shining spiritual quality—which remains in the mind long after you have seen her. Her dark, luminous eyes look out with almost childish innocence upon a complex world. One would expect to find her running barefoot in the rain or hooking her shoeless toes over chair-rungs at dinner parties as, indeed, she does.

Gadgetry of any kind delights but confuses Marisa. Walking toward the 20th commissary with a studio representative one day, she passed her small Austin convertible. A shower was threatening and the studio man expressed concern that the leather seats would be soaked. Marisa shrugged. “What can one do? If it rains, it rains.”

He walked over to the car and flipped up the canvas, expressly designed for such emergencies, which was hidden behind the seats. She was thrilled. “I never knew it was there,” she exclaimed happily.

America has opened up a bright new world to Marisa. In the past few years, she has changed from a shy, unhappy moth into a beautiful, gay butterfly and is loving every moment of her exciting new life. As for her whirlwind social life, she said, “In Italy, boys and girls do not have dates like they do here. They go out in groups, but if not in groups, they are always accompanied by an older member of the family. But in America,” she smiled, making an expressive motion with her hands, “they are free as the air.”

Does she approve of this greater liberty? “Oh, yes. It is delightful.” Then she added, “The boys here are so different, too. They are more independent. In Italy, the boys do more what their parents tell them. I like this better.”

The person with whom she has most enjoyed this new freedom is Jean Pierre Aumont. Before they finally admitted they were engaged, it was well-nigh impossible to coax easily frightened Marisa into saying anything about their “friendship.” However, it was easy enough to see this was more than a casual relationship. For example, a publicity man at 20th who—like others in his trade—can find revelations in downcast eyes, said: “During the making of ‘The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,’ Marisa was working on Stage 15 and Jean Pierre was working on Stage 5, at opposite ends of the lot. Between scenes, however, they often managed to be together. Guys and dolls don’t do that just to talk about the new books they’ve read or to work on crossword puzzles.” And, every time they appeared together in public—even though they tried to shy away from the spotlight, it became increasingly evident that what had started out as just a whiff of romantic smoke had blazed into a four-alarm fire.

Jean Pierre had returned to Hollywood to co-star with Jean Simmons and Guy Madison in “Hilda Crane.” It was then that he first met Marisa, and in no time at all they were smitten with each other’s charms.

At first, whenever she was asked to talk about Jean Pierre, Marisa would blush and say little. After a while, she answered such queries by quoting the famous song from “Oklahoma!”: “People will say we’re in love.”

So they were, and on March 27, in Santa Barbara, with only their closest relatives present, Marisa and Jean Pierre were wed in a civil ceremony, then took off for Hawaii on their honeymoon. After that, they planned to go to Rome and be married again in a religious ceremony.

While Marisa’s romance and sudden marriage was a pretty well kept secret, by Hollywood standards, her advent in pictures has been by no means as mysterious. Nor has it been a comfortable bed of roses. Her twin sister, Pier Angeli, had long been a star in the Hollywood firmament and Marisa, too shy to beat her own drums, permitted her less spectacular, more thoughtful personality to be obscured by the volatile, ebullient Pier. However, no strife existed between the sisters. The opposite was true. They had always been very close, as twins usually are. But Marisa had never shown any definite indications as to what she really wanted to do with her life. Their father, Luigi Pierangeli, a construction engineer, adhered to the traditional Latin concept that woman’s real mission in the world was to become a good wife and mother. He wanted his daughters to be reared as young ladies of culture and refinement, dabbling possibly, in such genteel activities as interior decorating or, perhaps, a little painting. He was shocked and grieved when Pier, who could always wind him about her finger, expressed her determination to become an actress. Marisa, however, was content to live under the shadow of her father’s dominating and masterful personality. That shadow was to hang over her in the form of her sister’s sudden rise to stardom in Hollywood, where the family came soon after Luigi Pierangeli’s sudden death.

“Pier couldn’t help me,” Marisa explained. “I myself wasn’t sure that I wanted to be an actress. I liked to write poetry and thought that possibly, if God willed it, I might become fairly good in that medium. But it wasn’t Pier’s fault that nothing happened to me in pictures. She couldn’t give me the incentive that I didn’t seem to have myself.”

But one night at a party, Marisa met Don Hartman, production manager at Paramount Studios. He had been observing her thoughtfully for some time, and he suddenly asked: “How would you like to have a picture career yourself, Marisa?”

Marisa was there when the studio gates opened. Hartman talked to her at length and then, to her utter amazement, offered her a stock contract.

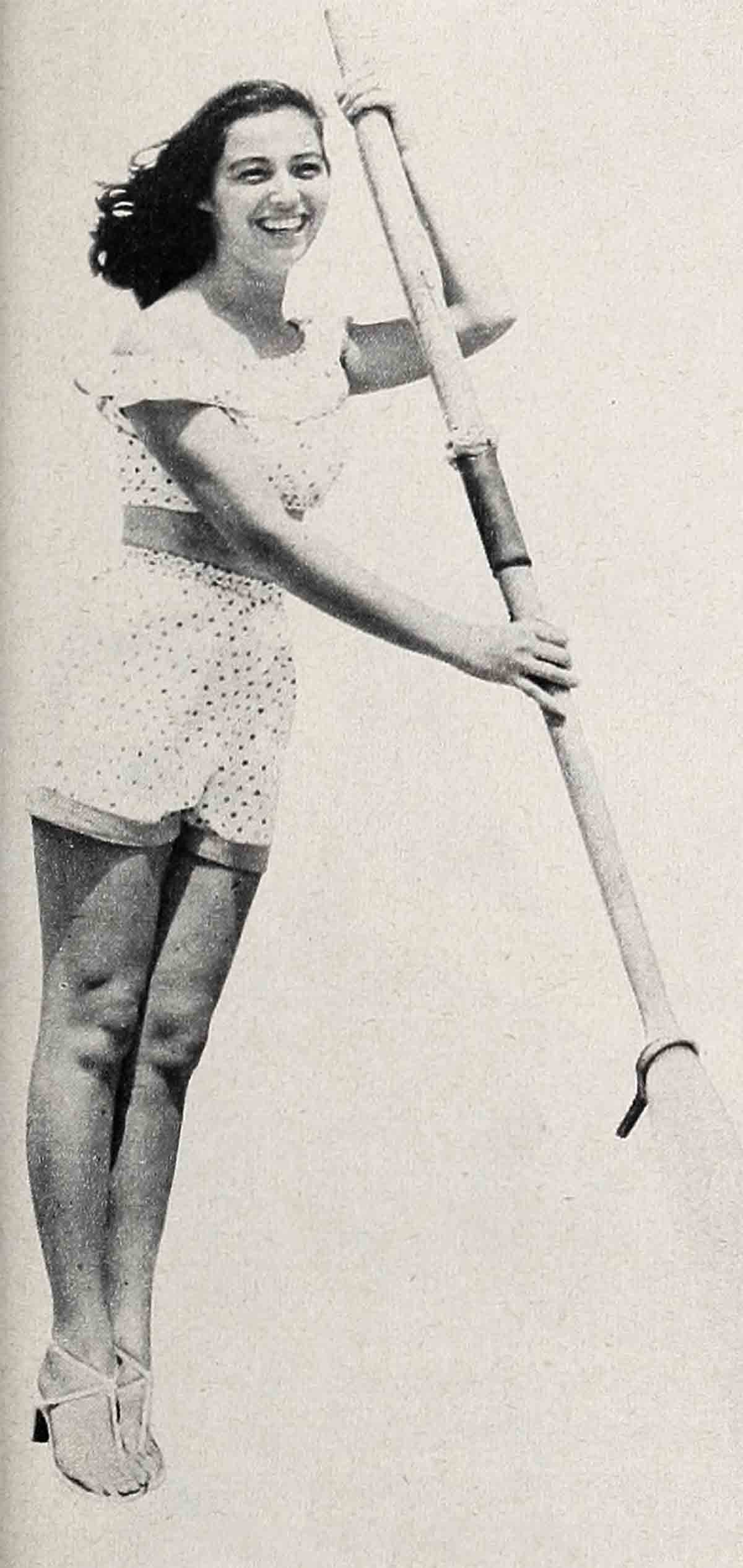

The next day she began her training in English diction, singing and dancing. (Dancing came quite easily, for in Rome, and quite unknown to Luigi Pierangeli, her mother had secretly arranged for Marisa to take dancing lessons.) “The training program was so wonderful for me,” she said. “The days went by like hours. I was always sorry when it came time to go home at night.”

And then, without the slightest warning, the first great blow fell. The US Immigration Department ruled that because she was in this country on a visitor’s visa only, Marisa could not be employed. Pier’s case was quite different, they said. She had come for a definite role and so was permitted to work.

There it was again, Marisa thought unhappily. The sun always shines for Pier She gets the icing off the cake. Everything good happens to her.

The following year was one of pain and frustration. But during this time an adjustment was made with the immigration authorities and as a result Marisa was offered a term contract with 20th and a role in “What Price Glory,” starring James Cagney, Corinne Calvet and Dan Dailey. Then soon afterward, her contract with Twentieth was cancelled.

Once more, Marisa hovered in the outer cold, staring through the windows where people more fortunate than she feasted on the sweets of the world. It was at this low ebb in her life that her mother, fearing the mental state into which Marisa had plunged, took her to Italy on a vacation. There in the warm Latin air and among the friends of her childhood. she learned her first great lesson, which was that the sun always shines for those who look for it and have faith. With this new-found philosophy, to which she clung almost desperately, came a chance to do an Italian picture, “I Have Chosen Love.”

After this was finished, and encouraged by the experience gained, Marisa returned to the United States. Almost at once she found a role in a picture titled “Case File, FBI” with Broderick Crawford. Following this she did some television shows and then “Drum Beat” with Alan Ladd.

Since she obviously could not appear in pictures under her own name, Pier-angeli (her sister having already adopted it), Marisa was forced to find another. Seeking one which would have a euphonious sound when coupled with Marisa, she thought of an old family friend, a general in the Italian Army, whose name was Pavan. She asked his permission to use it in her motion picture career and received a gracious letter of consent.

Soon after finishing “Drum Beat,” Marisa read Tennessee Williams’ “The Rose Tattoo.” Nothing had ever lifted her heart so much. She visualized herself playing Rosa, the daughter, and an unquenchable excitement rose in her mind. This was a dream—an impossible one, perhaps—but with her new philosophy, which told her that anything can happen if one believes deeply enough, the dream became so vivid that the role of Rosa assumed the proportions of reality to her.

A short time later, Marisa learned that Hal Wallis was to make the picture with Burt Lancaster and Anna Magnani. Breathlessly, she called her agent and demanded that he do something about securing the part for her. “Forget it,” he said, “They’re considering Pier.”

“I won’t,” she cried, her still-shaky English becoming almost unintelligible in her excitement, “ze least zey can do is to geeve me a test. Then, if zey still want Pier, I’ll be satisfied.”

A short time later, the agent phoned her. “It turns out that Pier isn’t available,” he said. “Now, if they give you the test, act awful pretty, baby.”

How “pretty” Marisa acted is attested by Nunnally Johnson. “I have seldom, if ever, seen a role more convincingly played,” he said. “She was not daunted, in fact, she was right at home with that magnificent actress, Magnani. You can hardly say more than that.”

Gregory Peck, in speaking of her work in “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,” said: “Marisa is an extremely gifted young actress. I think she will certainly become an important star.”

And, as a final salute to her great ability—the Academy Award nomination as best supporting actress of 1955.

Now on the dewy side of twenty-three, Marisa is trying to become as “American” as her eight-year-old sister, Patrizia, who considers herself to be definitely and positively American in all things. She also possesses a devastating sense of humor and delights in poking fun at Marisa’s still-marked accent. “Don’t talk like an Italian,” she shouts.

“But what shall I do?” Marisa asks meekly.

“Just don’t talk at all.”

After four years in Hollywood and no longer frightened by big-name stars and directors, Marisa has somehow kept that magical quality which distinguishes the young in heart, despite all the acclaim and the publicity that are beginning to beat upon her.

There is an old saying to the effect that almost anyone can stand failure but only the truly great can bear success. How will it effect this lovely little lady? Only time can tell. But at this stage of her young life it seems likely that, to parody the old song, she will “stay as sweet as she is.”

The END

—BY HYATT DOWNING

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1956