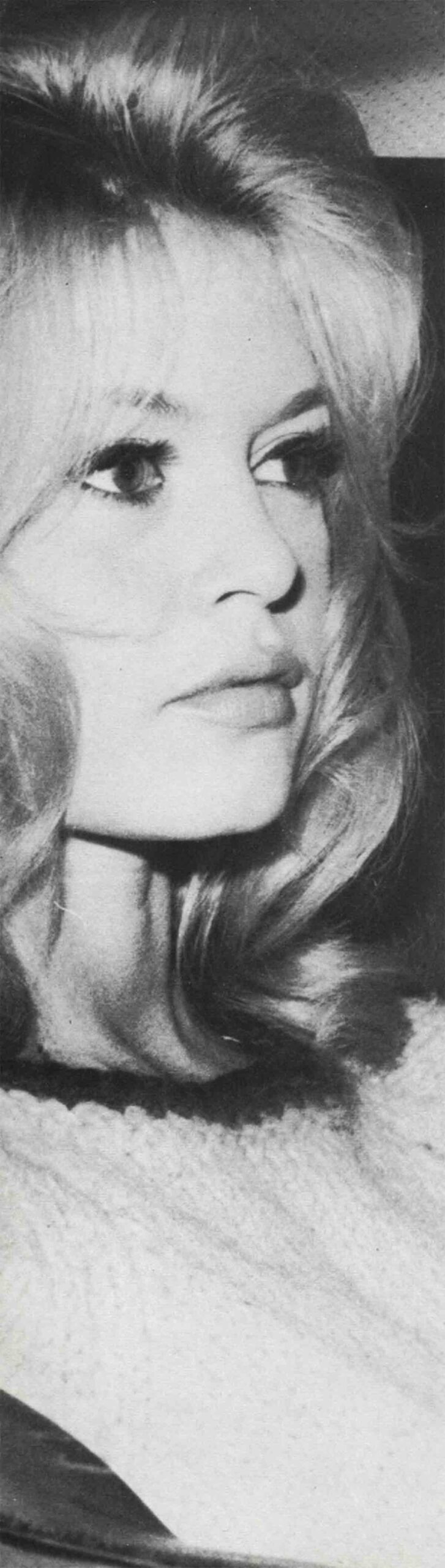

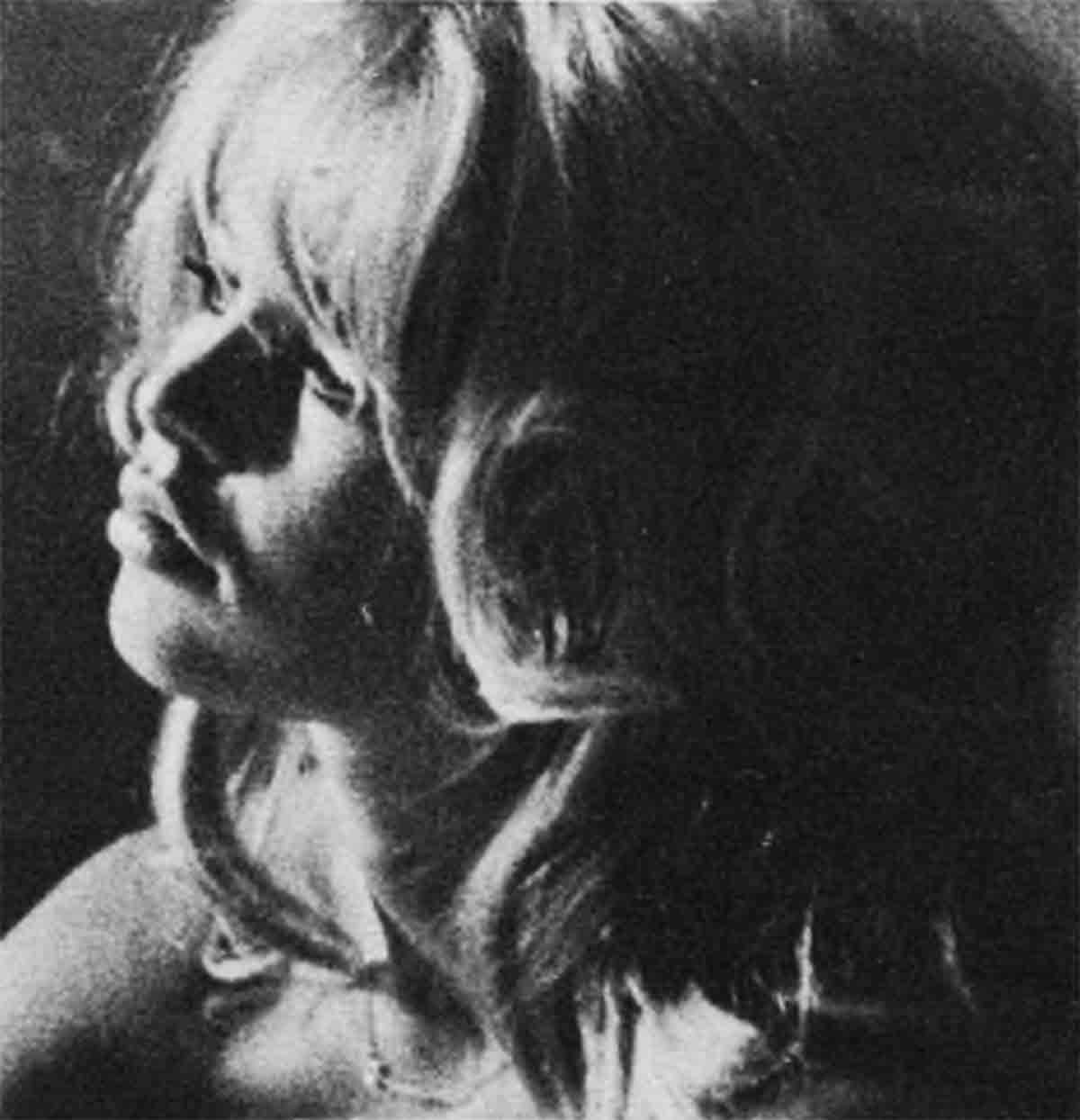

Will Brigette Bardot Be Another Marilyn Monroe?

When a beautiful girl is idolized by millions of men the world over, it would seem that she ought to be content and happy, particularly when she can earn thousands of dollars for simply making an appearance in front of a camera; so an American magazine reporter was understandably incredulous when Brigitte Bardot said to him: “I am now spending my life trying to erase the Bardot legend . . . I am now more anti-Bardot than anyone else in the world.”

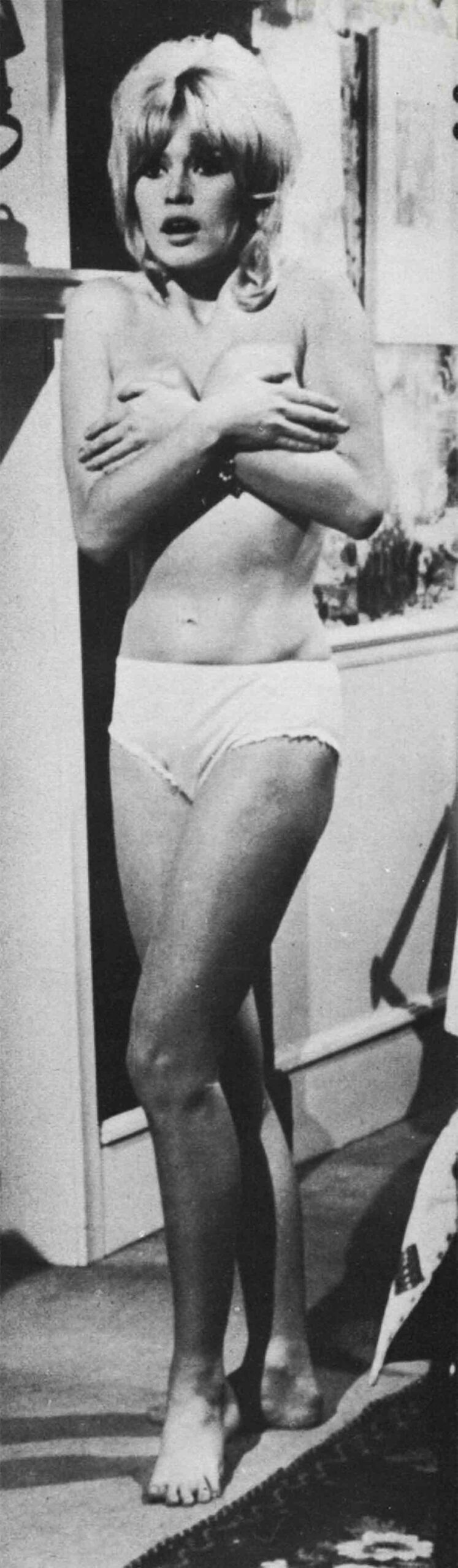

While the reporter puzzled over why anyone in the world should be anti-Bardot, Brigitte went on: “I have always played sexy roles and have never minded people seeing me undressed when the plot called for it. But now I want the public to see the rest of me.”

The reporter could not imagine what was left of Brigitte that had not already been seen by the public, but he shrugged and sent off the story anyway. He—and most everyone else—took the words lightly. They were either just typical female gibberish, or some press agent’s lopsided idea of publicity fodder.

It was not until after the death of Marilyn Monroe that anyone began to take seriously those words of Brigitte Bardot, For it seems that Marilyn had uttered almost exactly the same sentiments during one of her depressed moments. “I don’t want to play sex roles anymore,” Marilyn had said. “I’m tired of being known as the girl with the shape . . . The best way to find myself as a person is to prove to myself that I’m an actress.”

And thus, it begins to appear that BB and MM have shared more in common than blonde hair and alliterative initials. And when observers start adding up the many other similarities between their lives, some begin wondering if they will also run parallel in death.

Item: both beauties sought fame and fortune as compensation for lonely and troubled childhoods.

Item: both became victims of that great irony which afflicts international love goddesses: in appealing to the most basic instincts of human nature, they have been personally detached from their own identities as human beings. In a word, they became symbols.

Item: each has been loved and worshipped by multitudes of men around the globe—and neither one could find a single man capable of making her completely happy.

Item: both have gone through several marriages love affairs only to have each one end in disaster.

Item: both have been driven to the edges of nervous breakdowns by the hectic paces of their careers; and after a great deal of torment, they have learned to hate the mobs of fans they once enjoyed.

Item: both have made attempts at suicide—and Marilyn succeeded.

It would take a trained psychiatrist to determine what events led to Marilyn’s self-extermination, and to judge whether or not similar circumstances would lead Bardot to do the same thing. But any plumber can see that—regardless of the way of death—the tragedy of life teaches the same lesson in both cases.

The lesson, simply, is that fame and fortune are no substitutes for happiness. Marilyn herself discovered this when it was too late. She said of her early years, “I knew I belonged to the public and to the world—not because I was talented or even beautiful, but because I had never belonged to anyone else. The public was the only family, the only Prince Charming, the only home I had ever dreamed about. I didn’t go into the movies to make money. I wanted to become famous so that everyone would like me, and I’d be surrounded by love and affection.”

But she learned, the hard way, that public love is only skin-deep. In a Life article published the week before her death, Marilyn said: “Fame to me is only a temporary and partial happiness; that’s not what fulfills me. It warms you a bit, but the warming is temporary . . . Fame will go by—and so long, I’ve had you, fame. I’ve always known it was fickle.”

The Hollywood press agents will tell you that a love goddess is a woman who represents feminine perfection to almost all men. By very definition, then, her position is impossible. Any girl with a normal share of human faults must inevitably fail to live up to the symbol of perfection she is supposed to represent on the screen. That failure, in turn, leads to inward feelings of inadequacy in private life, and when marriages collapse on top of it all, the results can be severely damaging.

Then, such a girl begins to realize that even her most ardent admirers are in love not with the girl herself, but with an image enlarged to gigantic proportions on massive theatre screens, without any touch with reality.

Marilyn began to sense this when she said, “I feel as though it’s all happening to someone right next to me. I’m close, I can feel it, I can hear it, but it isn’t really me.”

The parallels in Bardot’s life are obvious. Like Marilyn, she became an overnight sensation on the sheer impact of her sex appeal. It was a different type of appeal, since Monroe was gay, bubbly, and naive in her approach to sex, whereas Brigitte is pouting, animalistic, and knowing. But the results were the same; the public was mesmerized.

Monroe said, “I never quite understood it—this sex symbol. I always thought symbols were those things you clash together.

Bardot was more coy in her remarks on her own sex appeal. She knew what it meant, and she played it to the hilt. When asked what was the happiest day in her life, she smiled and said that it was a night, not a day. When asked what she considered the most important thing in life, she closed her eyes and purred, “Love.” And so on.

But Brigitte’s awareness of her sexual attractiveness was only a thin armor. Eventually, it wore away, leaving her as exposed in real life as she was on the screen. In time, she became annoyed by the intrusions into her privacy. Wherever the sex kitten went, she was followed by a litter of copycats, as starlets and models throughout Europe began emulating her in hopes of picking up the scraps of fortune that Brigitte left behind.

When Bardot vacationed on the Riviera, that portion of the Mediterranean coast, from Nice to nearby Cannes, soon became France’s No. 1 tourist mecca. Looking for a more secluded sand patch where Brigitte could relax and sun herself, Roger Vadim—BB’s discoverer and first husband—came across St. Tropez, an obscure village on the Mediterranean that appeared to be a perfect hideaway. But no sooner did Bardot arrive than St. Tropez was also transferred into a heavily populated playground.

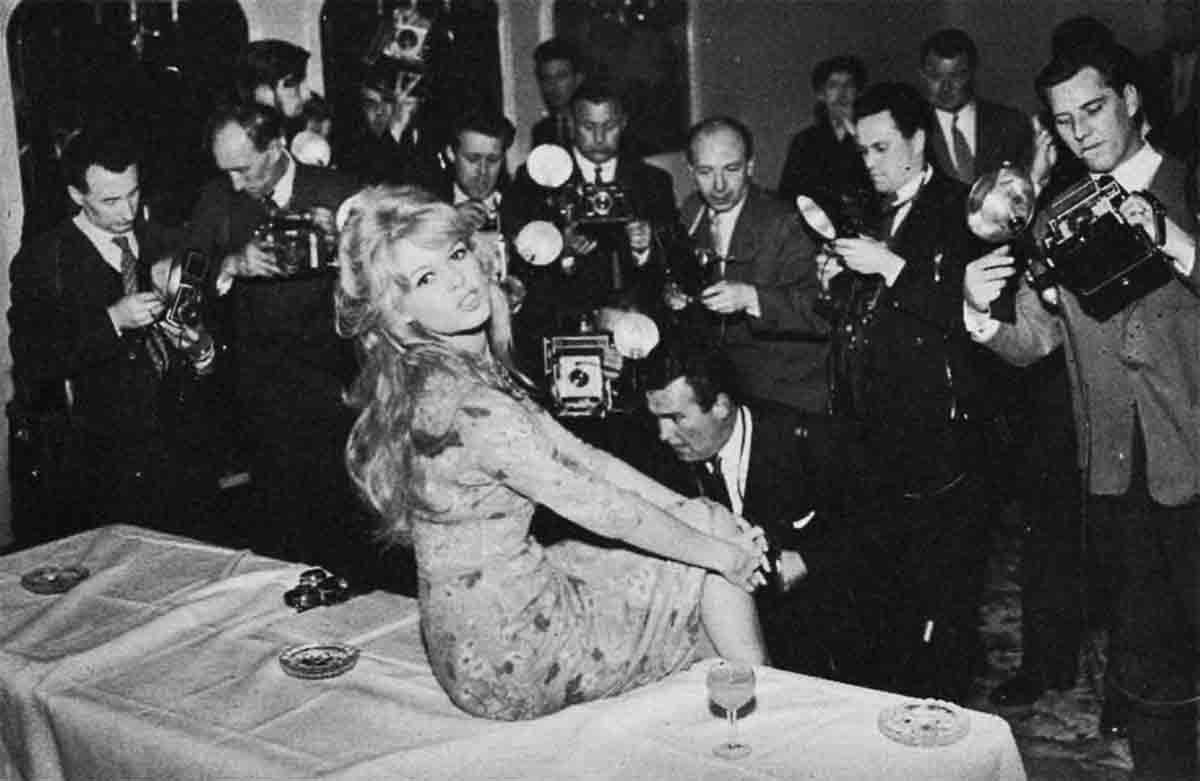

Adding to the turmoil was the constant presence of news photographers, who poked their telephoto lenses into every retreat where Brigitte tried to hide. Once, she was riding the Mediterranean waves on a water mattress, without her bikini top, when she spotted a spying telephoto lens on the shore. Annoyed—but powerless to do anything about it—she flattened out on her belly and scowled. On another occasion, an afternoon of cozy love-making between Brigitte and boyfriend Sacha Distel was recorded on film by a distant photographer, and the results have been printed in almost every major publication in Europe and around the world. When she began dating Sami Frey, he became so perturbed by peeping shutterbugs that he bought a shotgun and started blasting lensmen into high-tailing orbits. And in Rome, Italian news photographers rented helicopters to sneak photos of BB from the air above her swimming pool.

Then there were crackpots. While in Fiesole, Italy, Brigitte was awakened in her hotel room one night by a part-time drummer, part-time poet named Domenico Buono, who was kneeling at her bedside spouting amorous verse. Brigitte screamed for the police, only to have the press attack her for “shoddy disrespect” of an artistic, noble poet. From his jail cell, Buono said: “It’s not her body that interests me; it’s her soul.” Brigitte finally dropped the charges, but had to defend herself by telling reporters, “Even lovers have to sleep sometime.”

On another occasion, Brigitte was shocked to discover that an artist named George Comen was attracting considerable attention at a Paris art exhibit with a painting of BB in the raw, which he claimed had been painted “from memory.”

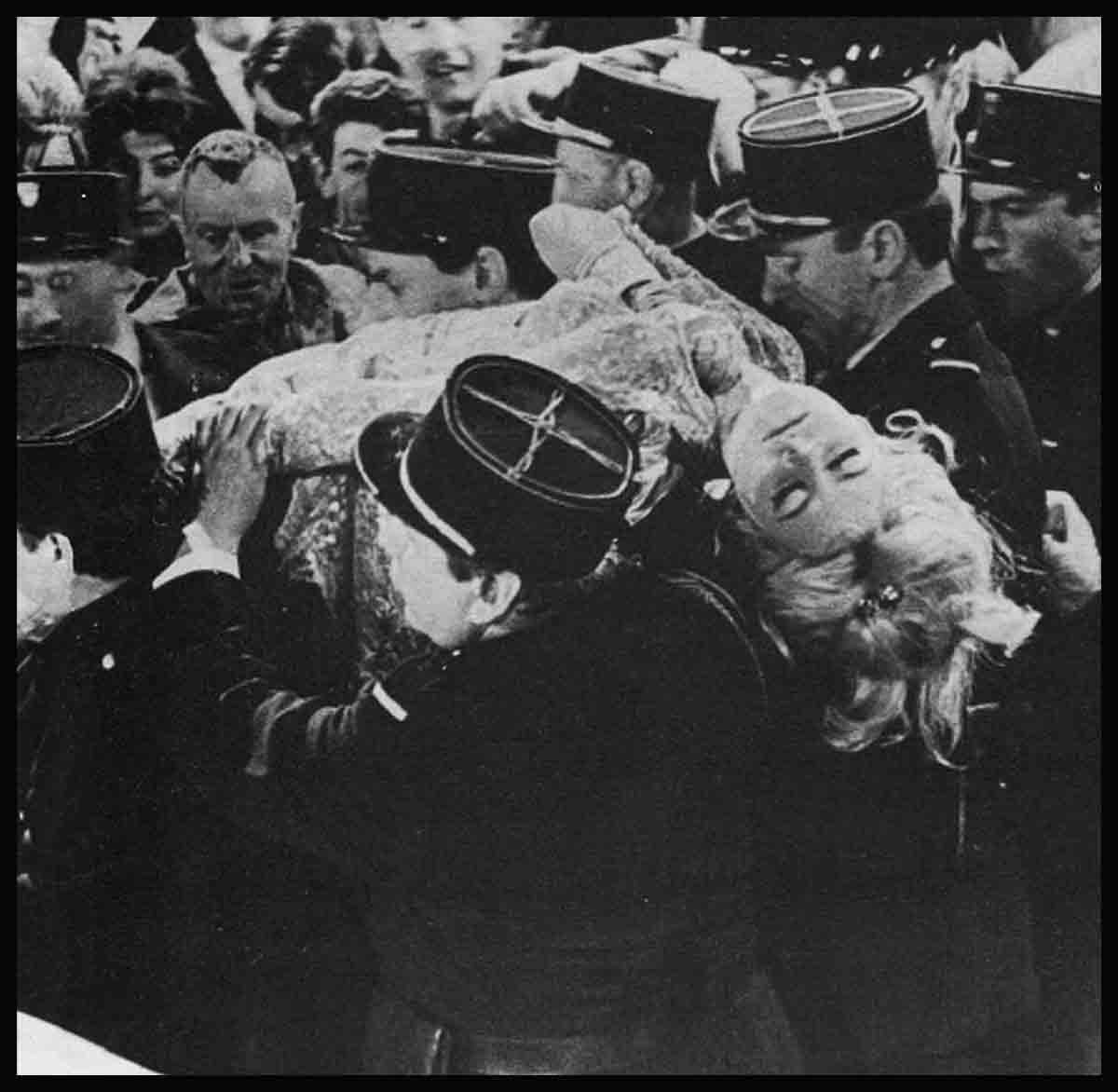

But worst of all is the public. Crowds constantly surround Brigitte with a sea of screaming faces and grabbing hands. Once, when Brigitte went to England to shoot key scenes for the motion picture, Une Ravis, sante Idiote, or The Adorable Idiot. The tumultuous welcome, however, changed her plans. Crowds surged around the sets, fights broke out, and even the battling bobbies were unable to contain the throngs of Bardot fans. Filming became virtually impossible, and BB was so frightened that she fled back across the English Channel to work in a “normal atmosphere.”

The total effect on BB, according to her mother, has been one of destruction. “The movies have ruined my daughter,” said Madame Bardot. “She lives on the edge of a breakdown. This is not success.”

Some time ago, another possible cause of Brigitte’s destruction was suggested by a Paris magazine; in an article entitled “The Man Who Destroys BB”, the magazine accused Brigitte’s male companion, Sami Frey, of doing her no good when he becomes violent each time she does a love scene on-camera with another actor. Frey took issue with the story and sued the publisher. And regardless of the decision of the Paris courts, it would seem that Sami is right in one respect: BB is not being destroyed by a man. If anything, she is being destroyed by the lack of a man.

Shortly after Marilyn Monroe’s death, millions of guys thought to themselves, “It’s too bad she never met a nice, lovable, sincere, decent, generous, and understanding guy like me. If she had, she probably would have been okay.”

Today, the same men are beginning to say the same thing about Brigitte. And yet, it is no reflection on Sami Frey, who—for all anyone knows—may be a swell fellow; nor is the Monroe tragedy any reflection on Joe Di Maggio, or Arthur Miller, or the Van Nuys, California, cop who was Marilyn’s first husband and who is now leading a happily married life.

Nor is there any reflection on Roger Vadim, BB’s first husband and director; nor on Jacques Charrier, her second husband; nor on Jean-Louis Trintignant, Gustave Rojo, Gilbert Becaud, Raf Vallone, Alain Carre, Sacha Distel, or any one else among the myriad of men who have moved in and out of BB’s tempestuous life.

It is, rather, a reflection on the way of existence that accompanies international stardom. A cafe owner at St. Tropez once expressed his views on the matter after lengthy observation of the BB crowd: “We are giddy trying to keep up with BB and her friends. First, she arrives here with one of her husbands, Roger Vadim. Then, she arrives with Sacha Distel. Then, Vadim arrives with the actress Annette Stroyberg, his new wife. Then Bardot comes with another husband, Jacques Charrier. Then, Distel arrives with Stroyberg. Then, Bardot arrives with Vadim! Who is with who?”

Despite this marriage-go-round or because of it, and despite the hundreds of proposals she gets every day from men who would sell their souls to her, Brigitte may never find the “right guy”, just as Monroe never did. The trouble is, every man in the world may be capable of making a woman happy.

But what does a guy do with a symbol?

THE END

—BY ALAN T. BAND

It is a quote. BEAU MAGAZINE AUGUST 1966