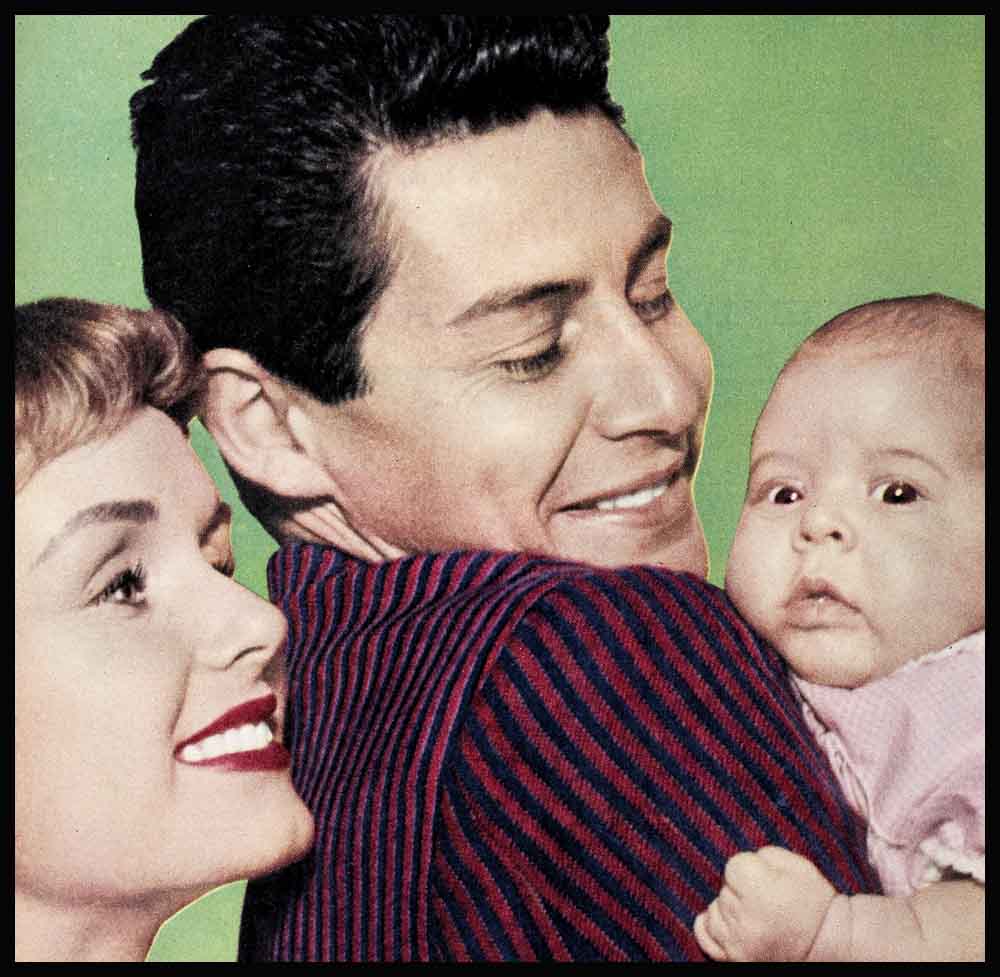

Love And Marriage And A Baby Carriage

Eddie Fisher came back down into the waiting room of the hospital with the happy, dazed look of a man who has been told—well, that he’s just become a father. In one hand he was holding a card, in the other an unlit cigar.

A group of his friends were waiting for him, and when he walked in they bombarded him with questions: “Who does the baby look like?” “What does he weigh?” and “How is Debbie?”

In the manner of a man who has just “had a baby,” Eddie answered wearily, “It’s not a he. It’s a little girl and she looks like me. And Debbie is just great.”

AUDIO BOOK

The baby came as a big surprise to her parents who weren’t expecting her for at least two more weeks. As Eddie said later, the stork was “jet propelled.”

Or, as many others commented, that bird just hovered over the set during the filming of “Bundle of Joy” and as soon as it was finished started flapping its wings.

Right after the picture the Fishers went to Palm Springs to spend the weekend. Debbie had a cold and they’d gone there for the hot desert sun. Her physician, Dr. Charles Levy, had told her that the rest would do her good and that he was planning to be there himself and could be reached easily if needed.

At midnight Dr. Levy’s phone rang. It was Eddie who said anxiously, “Doctor, I hate to bother you but I think Debbie . . The doctor didn’t give him a chance to finish the sentence. He dashed into the night and when he arrived at where the Fishers were staying he found Debbie bundled up to go to the hospital and Eddie seated behind the wheel of his car. The doctor took one look at Eddie’s face and said, “I’ll drive.” And they rushed into the night, Eddie and Debbie’s public unaware that the most awaited baby in the land was about to be born.

Actually there was no cause for alarm. Eddie and Debbie’s baby would be hardly discouraged by a fast automobile ride. Hers was a very hardy heritage.

Being born in a Philadelphia tenement hadn’t stopped the baby’s father, and Debbie wasn’t born with a silver spoon in her mouth, either, but to people who had hung on to life with a merry heart and a strong hand. Debbie’s infancy was spent in a two-room house in the back of a filling station in El Paso, Texas, where her dad worked fourteen hours a day.

When they drove up to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Burbank at four a.m., Debbie was whisked into a cheery corner room on the fourth floor. A soft-voiced Sister indicated that Eddie would be billeted in the waiting room. “That’s where the fathers work,” she said, smiling warmly.

Eddie put in a call to New York for his manager, Milton Blackstone, who made arrangements to fly out immediately. Then around Hollywood a few phones began to jingle, and sleepy voices came awake at Eddie’s jubilant: “I’m going to be a father!” Soon his friends were gathered in the waiting room with him, a close circle of those who had played a part in today’s happiness and fame.

They were a small group: Debbie’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Raymond Reynolds; Gloria Luchenbill, Eddie’s press-secretary, and her husband, Philip; Monte Proser, who produced Eddie Fisher’s NBC-TV “Coke Time” show—and who ran the Copa in New York City some years ago when an eager seventeen-year-old singer applied for a job. Proser had told Eddie that he was too young to sing in a night club, and sent him to Grossinger’s in the Catskills, where fame found him shortly afterward.

At the hospital, too, were TV-actor Bernie Rich and comedian Joey Foreman, boyhood pals from Philadelphia’s South Side. They had led the applause when Eddie sang for customers in Joey’s dad’s candy store. They had been sure he’d make it when he was singing for carfare on the local radio. And as teenagers dedicated to show business, they’d walked together up and down Broadway looking at the lights and dreaming of the big time; sharing their last thirty cents for beans at the Automat.

They ali had shared many great moments with Eddie Fisher. Now they were waiting in the wings again to share the greatest moment of them all. And while they waited, those who were fathers talked and talked about the pleasures and perils of fatherhood. Monte Proser gave a detailed account of the birth of each of his five sons. Just the day before, Bernie Rich’s pretty wife Marge had given birth to their first—a husky nine-pound son. So Bernie felt qualified to explain the wonderment of birth from a father’s point of view, going on at length about how Eddie would feel when “David Ross Fisher” was born.

“David Ross” was, as a matter of fact, the only name Debbie and Eddie had decided upon. The boy was to be named after Eddie’s friend, the late Jerry Ross, the brilliant young songwriter who had written “Heart” for him.

The group with Eddie were charting the whole future of “David Ross Fisher” when Dr. Levy came down from upstairs and said, “It’s time to go up.” A few minutes later Eddie Fisher was looking at a beautiful little doll, and losing his heart to her.

“Do you mind?” Debbie said, hoping he wouldn’t be disappointed it wasn’t a boy.

“Mind! Oh, honey, all I care about is that we have a beautiful little daughter and that you and the baby are well,” he said.

He called his mother at her supermarket in Merchantville, New Jersey, and announced, “Hello, Mom, I’m a Dad!”

“And how is the baby’s mother?” Mrs. Stupp asked in a calm voice. Debbie was her first thought and concern.

The baby’s mother was fine. The baby was fine. “Listen, Mom, I’d like to give you a cigar. I’ll mail it to you,” the baby’s father said.

Eddie called his father, Joe Fisher, in Philadelphia and gave him the glad news. And by then his fellow Friars, the other fathers in the lobby, had recovered their poise and were pressing him for further details.

“Debbie thinks she looks like me and I think she’s right,” he said happily. Who was he to dispute anything the baby’s mother said? According to the card in his hand, she weighed six pounds, twelve ounces. Then, turning the card over, he discovered for the first time the photostat of the baby’s footprints. “My baby has flat feet!” Eddie gasped, genuinely concerned. But he was reassured by the others that babies’ footprints always appeared that way.

In the opinion of Eddie’s friends, her first picture, taken by a hospital photographer when she was one day old, revealed that “from the nose down, it’s the Fisher face.” In the picture, her eyes are wide open and so is her mouth. She seemed to be singing, and, as one of his pals put it loyally, “probably the first eight bars of ‘Anytime.’ ”

They decided to name her Carrie Frances. Not for any special reason. Eddie says, “We just thought of that name. I like Frances—you know that’s Debbie’s name, Mary Frances, and we both liked Carrie.”

Asked who Carrie looks like now, he says, “You can’t really tell yet. She has dark brown hair. And she has Debbie’s eyes, great big eyes.” She also has, he suspects, her father’s voice. “She screams up a storm,” he grins, although he would cheerfully liquidate anyone who agreed a with him.

Naturally shy, it’s always been a little hard for Carrie’s father to express his feelings concerning those closest to him. He was frankly incredulous when some reporters wanted him to blueprint the baby’s future—even before she was born. And there are times when fame hangs very heavy over the heads of Carrie’s parents, when they would give anything to be able to enjoy every memorable day in the life of their baby without fanfare or publicity.

Photographers were camped outside the hospitial the morning the baby arrived. They asked to take pictures of her and were given a firm “No.” However, one photographer smuggled himself up during the visiting hours that afternoon and was caught with his camera against the glass of the nursery. He was promptly ushered out by the Mother Superior. From then on, the Fishers’ little pink-blanketed bundle was moved across the nursery and her tag turned away from the window to thwart anyone who might try to steal pictures of her.

Preparations for Carrie’s homecoming were complicated by her premature arrival. A survey of the baby-type wardrobe on hand revealed nothing but four little shirts, a nightie, and some diapers. She had gold rattles and silver rattles, gold mugs and silver mugs, but not one dress to her name. A layette was ordered.

Meanwhile, workmen were racing against time to repaint Carrie’s nursery at home and repair the effects of the fire which might have been so tragic for the Fishers. So tragic that they still mention it with a shudder and a thankful prayer. Debbie had just completed furnishing the yellow and white nursery, which had been planned around the elegant princess bassinet of pale-yellow satin and white organdy given Debbie and Eddie by the crew when they finished “Bundle of Joy.”

The $50,000 fire, caused by defective wiring, occurred on the only night Debbie and Eddie hadn’t slept there since they’d leased the house. Eddie was in Las Vegas discussing an engagement at Monte Prosier’s Tropicana and Debbie was spending the night with her parents in Burbank.

Contrary to reports, the few baby things they had were not burned. They were packed in boxes in the closet and untouched by the fire. But the yellow walls were smudged with black and the fluffy white curtains looked like old rags.

But the nursery was finally put in shining shape for its royal occupant. The furniture was scrubbed and the walls repainted; the elegant yellow satin-and-white organdy bassinet covering came back from the cleaners beautifully new.

If you ask Eddie about his first gift for Carrie he says casually, deceiving nobody, “It was a toy, just a little toy.” And you know it was probably a roomful of them. Carrie’s first flowers were forget-me-nots from Bernie and Margie Rich’s one-day-old son, with the message: “Please save the first dance for me,” signed “Michael Lewis Rich.”

From her New England farm, Bette Davis brought Carrie scads of home-grown yarn which will be made into fluffy hand-knits. Beloved Jennie Grossinger, who gave Eddie Fisher his first big chance, presented Carrie with a lifetime gift, a diamond heart-shaped pendant to match, in mother-daughter style, the one Eddie had designed for Debbie on their first anniversary, September 26, 1956. Eddie’s pal, fighter Rocky Marciano, gave her a diamond ring, which inspired Carrie’s mother to sigh, “Now that will make her a real princess.”

As for Debbie and Eddie’s fans, they’ve really taken little Carrie to heart. Eddie’s 4,750 fan clubs vied with each other to make her a special honorary member of “The Fisherettes,” with her own gilt-edged membership card. And they showered her with gifts of every description.

One day recently, after Eddie’s TV show, a pretty dark-haired girl pushed through the audience and handed him a small, prettily-wrapped package. “It’s for Carrie,” she explained. “Her first mink toothbrush.” An eighty-six-year-old fan sent a blanket she said she’d knitted while watching Eddie’s show. “I’m sure you couldn’t buy anything with more love in it.” Carrie’s parents got pretty misty about that one.

Eddie acknowledges such presents with a warm note, assuring them that, “Debbie and I and our little one are humbly grateful for your good wishes and prayers.” He worries when fans send Carrie expensive presents. “If only they wouldn’t spend so much money!”

At Eddie’s shows, fans always want a first-hand report on the women in his life. And they get it. “How’s Carrie?” they chorus. “She’s fine!” he beams. “How’s Debbie?” asks another group. “She’s fine, too,” he affirms.

Even though Eddie comes from a large family and grew up with a younger sister, he says that where babies are concerned, “I haven’t had too much experience.” But as a father, take Debbie’s word for it, he’s the best.

Working with one-year-old Donald Gray in RKO’s “Bundle of Joy” was a pretty good warm-up for Eddie’s duties as a father. As director Norman Taurog says, the Fisher charm has a way even with little bundles like these. In one scene Taurog was having no luck getting Donald to smile for the camera. “I didn’t know what to do,” he says. “I’d used all the hand props—the squeakers, everything—with no success.” Suddenly Eddie stuck his face next to the baby’s and said, “Hi!” A big grin came over young Donald’s face. “We rushed the shot,” says Taurog.

“I guess you don’t need me here the rest of the day, huh?” Eddie kidded him later. “You—the great child director!”

There was some speculation that Debbie would cancel out of “Bundle of Joy” when it was announced she expected one of her own. She was already committed to make “Tammy” at Universal-International, and people weren’t sure whether she’d want to work in two pictures during her last six months of pregnancy. Besides, a musical means twice the rehearsing, twice the effort, and usually double the shooting schedule.

Debbie, however, was determined to make the picture. As a close friend puts it, “Debbie wanted to do this more than anything, and I think she had nobody but Eddie in mind. After all, it’s his first movie.”

For years Hollywood had showered Eddie Fisher with fabulous offers, but he’d turned them down because he couldn’t find the “right” script. To producers, Eddie made it very plain that he was a singer, not an actor. Show him a script that was three-quarters music, and he’d see. . . .

When he found his “right” script, it was the musical remake of “Bachelor Mother.” ‘I’ve been a long time looking,” Eddie said. “But this is it. It’s a great story for me and for Debbie, too.”

Norman Taurog was concerned about how Debbie would feel during the filming. “This fine girl,” he announced later, “never once complained of the baby or of feeling ill. If you asked her how she was, she would say, I’m fine, I’m just great.’ And the way she said it, you believed her. That is, until the day Debbie couldn’t hold up any longer.”

They were getting ready to shoot an important scene when Eddie came up to the director and anxiously asked, “Have you taken a look at Debbie?”

“No, not in some time,” Taurog told him.

“She doesn’t look well. I’m worried,” Eddie said. “Are there any scenes you can shoot without her?”

The director took a look at Debbie then and sent her right home. “Honey, if you come in tomorrow, I’ll stay away,” he told her. Pale-faced Debbie just said, “Thank you very much,” and squeezed his hand.

Debbie’s doctor put his foot down, too. After that they closed the set. A policeman was stationed at the door. No interviews, rest during lunch and back to the dressing room after every scene were the strict orders.

Their picture was finished three days ahead of schedule and Debbie and Eddie gave the director a gold record inscribed: “To Dr. Norman Taurog, who delivered our ‘Bundle of Joy’ ahead of the stork.”

Today, the pleasure Eddie Fisher gives to others is coming back to him threefold—Debbie, Carrie and a tremendously successful career. He doesn’t know what his next movie will be—he’s waiting for the reaction to “Bundle of Joy.” As one friend says, “Eddie won’t make another picture until he finds out what the fans think of this one. They’ll tell him and you can be sure he’ll listen.”

“We’ve formed our own company,” Eddie says, “called Ramrod Productions, and there are several things we’re talking over, including a remake of ‘The Clock’ at M-G-M as a musical. That’s the picture which starred Judy Garland and Robert Walker.”

Television? “They’re talking about some TV spectaculars and a half-hour show, but I don’t know about that yet.”

Meanwhile they have time to get used to their new home, the one they’ve just purchased in Beverly Hills. It’s a lovely English-style house on two acres with a brook running through the garden.

Carrie’s pale yellow-and-white kingdom overlooks the garden, and the sun shines warm and bright through the windows most of the day. Debbie has arranged her daughter’s menagerie of toy animals so that they encircle the room like a frame. And here the little princess sleeps and sleeps under the watchful eyes of tall, inquisitive giraffes, shiny black poodles and playful kittens. When she wakes there is a bounty of royal toys to play with, gifts from her parents’ friends and fans.

Eddie’s improving in his fatherly duties, with constant practice. The other day he was telling a pal about his prowess in burping the baby. “it takes Debbie twenty minutes to burp Carrie, but I can burp her just like that,” he said, snapping his fingers.

“He’s right,” Debbie agreed. “It takes me longer. But with Eddie—right away.”

“That’s because she knows he has no time to waste,” the pal said.

But for Carrie’s father and mother, time begins and ends today with the little princess who is unaware of her millions of subjects. Her most devoted ones, of course, are the lovely merry girl who holds her so tenderly and the dark-eyed fellow who sings her lullabies. Carrie Frances Fisher’s every coo is their command.

THE END

YOU’LL ENJOY: Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher in RKO’s “Bundle of Joy”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1957

AUDIO BOOK