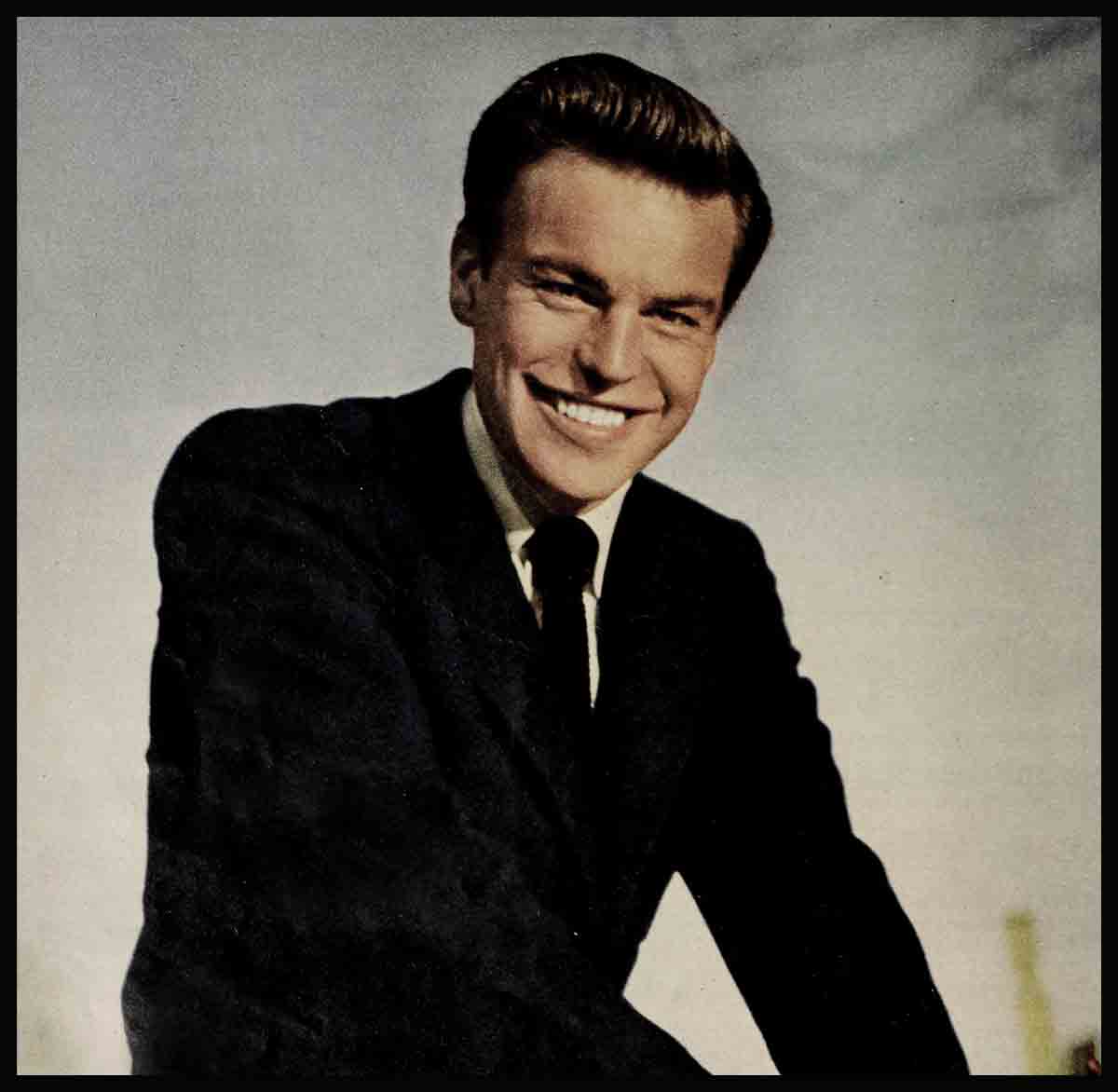

You Gotta Elevate!—Robert Wagner

“You know,” said Bob Wagner, “I’m the luckiest guy in the whole town. And,” he added, “I’m on about the roughest spot.”

“Come again?” I puzzled. “What did you say?”

Bob grinned. He’s got a great grin, ‘simply great. It’s a grin that would charm a cobra before it could spread a hood. “Come on over to my room,” he said, “and we’ll put on some music. I can talk then. It soothes the savage beast.”

“Breast,” I corrected.

“For me,” he kidded, “it has to be beast!”

I had dropped in on R. J. out at his film factory, Twentieth Century-Fox, as I like to do every now and then to check up on the progress of my favorite boy. I like Bob, and I always have. I first met him in the days when he was just another handsome young Hollywood Joe hoping to get started in this acting business. His folks were taking care of him and the most serious concern he had in the world was trying to talk Debbie Reynolds into a date and straightening out his two-iron pokes at the Bel-Air Country Club.

Lately, the dropping in had gotten a little tougher. In fact, this trip I’d waited about a month before I could catch up with Wagner. So I wondered if some of the sharpies around town could possibly be right; that is, that all this swoon star business which has suddenly seized Bob by the seat of his slacks was making a very nice fellow impossible to get at and more impossible to get along with. I didn’t believe it, but a reporter has to find out those things for himself.

I had asked Bob right off how he was doing and he came back with that cryptic crack. Furthermore, I seemed to notice that his old faithful smile buttoned itself down again in a straight line a little more quickly than it used to. Could he have problems?

Bob loosened his collar before he answered, peeled off the blue flannel jacket with the red lining, stretched out on the sofa and elevated his phosphorescent pink socks into the air. Two black tasselled loafers dropped off. “Get them,” grinned Bob. “Crazy but comfortable.” He got up as soon as he lay down and slipped some LP’s on the record machine.

“You like Jackie Gleason?” he inquired. I said he was a very funny man.

“I mean his music.” he said. I didn’t know he played music. “He doesn’t. He arranges it,” said Bob. “Now, that’s what I mean. Listen—there’s a man with real talent. I met him in Detroit last trip and he’s out here now on vacation. I’ve been hanging around. Maybe I can learn something.”

“What do you need to know?” I wondered.

“Oh, nothing,” said Bob, “and everything. I’m having a ball, all right. Look, I’m making great dough, getting great parts. I’d rather be where I am, doing what I’m doing than anything. I’m on top of the world. I’ve got great people all around me. I couldn’t be fatter—only, it’s just the bushwa. I don’t want people to think I’m a phony.”

Who was thinking?

“Maybe nobody,” admitted Bob, “and maybe everybody. I don’t know. All I know is that I’ve got to keep hold of the wheel. I’ve got to keep control and I’ve got to improve. Got to lift, lift, lift. Get some class. Do you know Clark Gable?

“Well, I saw him the other night in New York. Now there’s a really great guy. They don’t call him “The King’ for nothing. I used to hang around the caddy shack at the club when I was a kid hoping for a chance to pack his bag. Sometimes I got it. If I didn’t, I followed him around. He was always swell to me, always my idol. Still is. So when I saw him in Twenty-One I went right up. He’d been in Europe for a long time but I might have seen him yesterday. He said some pretty nice things about me, said he was proud of me—stuff like that. I should have felt my feet leaving the ground. But I didn’t. I just felt embarrassed—like a peanut—and scared. Why? Oh, I don’t know, all this swoon guy stuff and everything—”

“Gable went through it,” I pointed out.

“Sure he did,” brightened Bob. “And so did Bob Taylor, Ty Power, Jimmy Stewart, Cary Grant. They all did. But they managed: to keep people’s respect—and now look at them. That’s what I’ve got to do. Earn respect.”

So Bob Wagner is worried. Not about the things that usually worry a young star in Hollywood. Not about money, not about girls. Not about his option, either. But still worried because, “It’s all come too fast. I didn’t count on it this way. Don’t I want to be a star? Sure I do. I always did more than anything in the world, ever since I ran into those great people around the club—Gable, Alan Ladd, Randy Scott and the rest. I always said, ‘That’s the business for me,’ and I sure enough meant it. But I’m not a star. I’m a long way from being a star.”

“You were in Prince Valiant,” I reminded him.

“I had the title role,” corrected Bob. Then he took on the pained expression of a father trying to point out a fact to a small child. “But look, it takes two to tango. It takes directors, writers, technicians, other actors who know ten times as much as I do—a hundred people—to make a picture great. Mine have been great, but not because of me. Got to move. Girls have started sleeping on the steps of my apartment. Why? When I went to the opening of How To Marry a Millionaire in New York a few weeks ago four cops had to usher me across Times Square. Cops— imagine! I wanted to drop through the pavement. What’s the big attraction? Not really me, not my talent. Up in New Haven 2400 girls hung around the lobby three hours before the picture opened! And down in Florida on location—the things that went on were fantastic. Why?”

“Wait a minute,” I interrupted. “I know plenty of young actors who’d think that was swell.”

“It is. It’s wonderful. I love it,” admitted Bob. “I like fans. I’m a fan myself—the greatest. Listen—I was sitting in the bar at the Sherry-Netherland Hotel right by the window—and every ten minutes a gang of kids came up outside. I got up every time and went outside until they had what they wanted. I had an awful time getting one drink down. I was flattered; it made me feel humble. But—well, I hope they all go to see my pictures. See what I mean? I don’t want to be a red hot pure publicity flash in the pan. I want to elevate, man, elevate, grow and rate all this!”

Have a cigarette,” I suggested. “That is, if it won’t stunt your growth.” Bob laughed, lit it and relaxed on the couch and I felt like a psychiatrist with Bob talking it out. But I think it was good for him.

Robert John Wagner isn’t like the average run of Cinderella boy who collects fast fame in Hollywood. What’s hit him isn’t a natural development from his beginnings at all. He hasn’t struggled up from nothing. He hasn’t even a show business background. Of course, that “born with a silver spoon” malarkey is just that. It gives Bob a pain to read that he’s a rich man’s son. He isn’t. His folks are just comfortable middle class people. But it’s true that because of his conservative bringing up he belongs in the limelight about as much as, say, a steel salesman. That’s what his dad, R.J., Sr., is and that’s what Bob undoubtedly would have been if the Wagners hadn’t decided to transplant the family home and business to southern California when their only son was still a pup.

Even if he tried, Bob Wagner couldn’t pull away from the legitimate slant to everything he does. What put the acting bug in his noggin in the first place was not a crowd of starry-eyed kids from the Studio Club or the Hollywood-and-Vine extra set living off their cuffs to hang on in Hollywood and have a good time. The idols Bob shagged balls for around the Bel-Air Club weren’t Johnny-Come-Latelys or fly-by-night promoters. They wouldn’t belong to Bel-Air if they were. They were the cream of the crop, seriously and successfully wrapped up in one of the most fascinating games the world has ever known. And what lodged inside Bob Wagner’s handsome head was not only that fascination but also respect for the people he identified with it. They were deadly serious and intelligent about their business. And from the start that’s what Bob was determined to be, too.

The whole thing has been R.J.’s own special show. Nobody bucked him at home. The Wagner family always gave Junior his head and helped when necessary. It was his own pal-type dad who skeptically but loyally promoted Bob’s first look at a movie camera with a club friend, Director Bill Wellman, to start him off. The understanding pop lent Bob, all in all, about $4000 to get started, every cent of which Bob has just paid back. Still, to Bob Wagner the whole thing has been a unique personal challenge. It’s no lark. It’s his adopted profession and life’s work, and that’s exactly how he looks at it. Now he’s got to make it important, dignified and real, or in his book he has failed. And beneath the pretty profile and peach bloom cheeks of Bob Wagner’s good looks there’s stuff as sturdy as the product his dad still sells. That’s why the hey-hey and hoorah that’s swept down on him is disturbing. He’s convinced it is destined to goof out and leave him flat if he doesn’t fill in behind the blown-up fame—and fast.

“Right now it’s like stepping from one puddle of water to another,” Bob sized up his career. “You lift a foot out of one pool and it closes behind you. There’s no place left there. The newcomers are already filling it. You’ve got to make a place for yourself in the one ahead. Right now I’m between puddles.”

He’s right. There’s no standing still and no going back in Hollywood. Someday, Bob believes, all this avalanche of popularity will roll on past him, as it has rolled past every other young star sensation before him—and what then?

“A bunch of us here in Hollywood all hit about the same time,” observed Bob. “Tony Curtis, Aldo Ray, Rock Hudson and some others. We’re all in the same boat. The joy ride doesn’t go on forever. I’ve been a lot luckier than most. Oh, I haven’t done as many pictures as, say, Tony, has—but what breaks I’ve had! The people I’ve worked with! The top productions I’ve lucked into—With A Song In My Heart, Stars And Stripes Forever, Titanic, 12-Mile Reef—in CinemaScope—and now Prince Valiant. Why, no other guy I’ve named has had breaks like that. And if I get Broken Lance—cross your fingers will you?” He shook his head in wonder. Then Bob rattled off some of the actors he has worked with. “Don’t you think,” asked Bob hopefully, “that some of that talent could maybe rub off?” I thought a lot of it already had. But he shook his head. “Not unless I mature,” he said. “That’s why I’ve got to lift out of this kid level. Got to switch on some dignity and duck the foolishness.”

R.J. Wagner is pretty serious about this. At his studio, he has already laid down the law against gag pictures and layouts. He won’t make eyes at girls for sweet publicity, or fake silly shots. He gives a flat “No” to ideas like, “How My Girls Should Act on A Date,” “My Ten Rules For Popularity” and such. He’s concerned about the wolf peg that’s being hung on him—as it has been hung on every movie dreamboat in his spot Before! Bob dropped a new stack of records on the spindle to soothe the savage beast before he went into that.

“From what people read,” he said, “you’d think I spent all my spare time chasing girls and partying around. Why, I haven’t taken a girl out to a big Hollywood deal since I took Mona Freeman to the premiere of The Robe. Parties—I just don’t care for parties, never have. When I do go I stop in early and leave early. Somebody asks me why I’m leaving and I say, ‘Got to get up early and vote.’ ” Bob grinned. “Now, I like girls all right. I’ve got girls stashed away that I see all the time, swell girls—you wouldn’t know them—but I don’t see them in public if I can help it. Have you ever been ‘a romance item?’ ” asked Wagner.

That is part of the routine Bob’s stuck “It’s okay,” allowed Bob, “if it were true. But it isn’t and then it’s embarrassing to get tied up in print, not only for me but for the girl. I took out this girl, Josephine Abercrombie, in New York. A wonderfully nice girl. (Her folks run the big Abercrombie & Fitch store.) What do you know? Next morning somebody says I’m trying to marry an heiress! Marry her? I just met her! Things like that happen and what’s the result? I add up like a jerk. So I just have to watch it and now and then get unhappy about it.”

Not long ago, Bob recounted, he was paired off in a personal appearance junket with a starlet who shall be nameless here. When he climbed aboard the plane, there was a press agent by the girl’s side putting a ring on her third finger. “An old family heirloom,” he explained. “Let’s get a picture.” Bob can think fast. “Uh-uh,” he declined. “Either the ring gets off the plane or I do.” And he started for the door. Well, the same stunt was tried again. Both times he had to get tough about it, although he hates to be that way.

It’s no secret, although Bob didn’t say so, that he blew his stack more than he ever had before when that romance fiction about him and Terry Moore began hitting the newsstands while they were making 12-Mile Reefin Florida. Terry and Bob have been thrown together plenty luring the course of two careers that began to roll about the same time in the same place. Both are young and attractive and red hot in popularity. So what can you expect, by all the past, present and future formulas of Hollywood ballyhoo? But Bob just has other ideas about that sort of thing. He likes Terry, but he doesn’t like being pictured as her love captive—not for a minute. There was more than one long distance call back to Hollywood from Florida and the message was, “Try to stop this—please!”

That’s the difference between Bob Wagner and the usual young Hollywood shooting star. He won’t use just everything for fuel to jet propel himself. He wants to rate the ride.

“I don’t want to sound like a square or a snob,” said Bob earnestly. “I don’t think a am. But look, it’s only good sense. You can’t build a business on baloney. If you lose your honesty, if you ditch what you believe in, then it comes across on the screen. You’ve got to be somebody or you don’t look and act like somebody. It’s as simple as that. But really to be somebody I’ve got a lot to learn. And now’s the time for me to buckle down.”

To Bob Wagner his studio is his college. After prep school he had planned to take a course in business administration at Claremont Men’s College. Acting jobs stopped that, but he’s taking it just the same—right ‘where he works. Bob’s on intimate terms with everyone, from the Skourases to the studio bootblack. Back east he trails through the business offices and buddies with the secretaries. He’s at home in every department connected with pictures, selling, distributing or showing them. Away from work his best friends are not kids his age interested only in their weekly checks and in having a ball. They’re older people who can teach him the thousand things he’s determined to know—people like Directors Walter Lang, Sammy Fuller, Eddie Dimytryk, Henry Hathaway, Mary and Richard. Sale, the writers. He keeps an inquisitive pipeline open to every corner of the lot. Bob bought 100 shares of TCF stock last year and although it has almost doubled in price by now he wouldn’t sell it if it hit the skies. He brought out a loose leaf file and riffled through it as we talked. “Stories,” said Bob, “I read a lot. Some of these the studio has bought. You never can tell when there might be a part for a guy like me. Take Prince Valiant, for instance—”

Bob got that one strictly by his own initiative. He took the idea of the dashing medieval character right out of a comic strip he clipped and brought it into the office of producer Robert Jacks, Darryl Zanuck’s son-in-law. Jacks liked the idea and promised to look into it. “When you do,” suggested Bob, “give me a chance at the wig, will you?” Bob Jacks said he’d do. And, of course, Wagner wore the wig—for the best part he’s had so far. What’s more, the job he did there has already cinched him for another swashbuckling title role in Lord Vanity,the Shellabarger novel.

“The roughest time for me is between pictures—like right now,” sighed Bob. “Look at me—jumpy as a witch. Can’t settle down. I’ve lost nine pounds. You know, I really go off my nut when I’m not working. It’s such a great kick to start a picture. I’m really living then. But you hit such a pace! When it’s over, I can’t cool down.”

Bob used to cool down pasting a golf ball around the Bel-Air links. He’d still like to, but that is mostly a vain hope these days. “My mother gave me a beautiful golf set for Christmas,” he said. “New rocket shaft Walter Hagen clubs, a terrific bag, black leather with red lining—that’s my favorite color combination—but you know I haven’t had a chance to break it in yet, My game’s gone to pot. Dad beat me down in La Jolla and the boys at Bel-Air are going to take all my money when I get there. I just don’t have time any more to practice. I get as far as the locker room, the telephone rings, and I’m back on the hook. It’s a layout—or an interview.”

“Like this.”

Bob grinned. “Like this. And it’s swell with me. Don’t get me wrong. I’m lucky you’re here. But what can I tell you? I’m such a dull character. All work and no play.”

“You’re not kidding me,” I told him. “With you there’s strictly no difference.” That’s what makes Bobby run. He’s just plain crazy about his job.

“Come on,” he fidgeted. “Let’s get out of here. Take a tour around the lot, hey? Got to look after my interests.”

So we took a tour around the lot. That is, it was a tour for me. For Bob Wagner it was just the daily and often all-day round, but he wouldn’t trade it for a trip to the moon.

He couldn’t take a step without somebody’s hailing him. “Hey, Lover-Boy!” shouted a guy from the catwalk around the cutters’ building. “Love her yourself!” yelled back Bob, “Everything under control?”

“Better Come up and check.”

He moseyed into the make-up department with all those mirrors, hair dryers and barbers’ chairs. “See my Broken Lance test?” he asked the head make-up man anxiously, and got a nod. “How’d you like it?”

“Too dark.”

“It’s the photography, not. the makeup,” decided Bob. “Let’s go in here.” He pushed open a heavy door. Inside the dubbing stage hell was popping on a giant screen, as G.I.’s got drilled by machine guns. From the controls a chorus of voices greeted, “Hi, Bob,” and went on with the slaughter for Hell And High Water. “Great reel,” Bob told them after the lights flashed up. “Knocks you out of your seat.”

“Thank you, Mister Wagner,” bowed one in mock servility. “Yes, Mister Wagner. Then it’s okay to go ahead?” But you could tell they loved the guy. Bob grinned.

“What a crew!”

At the scoring stage a huge symphony orchestra thundered music as a tense Demetrius scene unreeled. The orchestra stopped midscore and everybody laughed. I didn’t see why. “Piano forgot to come in,” explained Bob.

“You lead orchestras, too?” I asked him. He laughed.

That’s how it went all over the big plant—wardrobe, camera shop, make-up, script, a couple of dressingrooms and a few sound stages. Nothing exactly new to me but through Bob Wagner’s eyes it did indeed seem wonderful, fabulous, fantastic and great. Those eyes were shining as we sat down in the cafe for a Coke.

“You know,” said Bob, “sometimes this seems like a crazy town and a crazier world. Here I am just an ordinary twenty-four years old, with all this luck and all this fuss. I’ll go home now to my apartment, $125 a month, furnished with some things my folks left me when they moved—all I need. But I’m looking for another one, bigger and custom furnished with a whole new deal. For a while I thought about a house. Almost went for a made-over stable on a big place in Beverly Hills. But $39,500! Wow! I couldn’t swing that. Actually, why should I want a house? Other day I tried to buy a horse named “Steel” in one of my pictures, but they wouldn’t sell him. What would I do with a horse? Can’t ride it. My bum eardrum hurts when EI bounce. Just pet it, I guess.”

“I spend a lot of money on clothes. This coat now, custom tailored, and these slacks by Hoffman-Tarzia. I don’t really have to have clothes like this. Cars have cost me a lot, too. Lost money on trades—my Cadillac, MG, Ford, Mercury. I cracked up a couple. When I eat out, which is all the time, it’s at Romanoff’s or Chasens. Expensive. I came back from Florida broke. I’ve got a business manager now who’s holding me down. What I mean is, sometimes it all seems crazy. Me, in a seventy per cent income tax bracket!

“I’m just the same guy I always was,” Bob soliloquized. “But people say I’m a star when I’m nothing of the sort. They expect me to act differently, be different. Kids write letters and people ask me questions, as if anybody cared. ‘Are you in love?’ ‘When are you going to get married?’ ”

“Well, when are you?”

“Someday, I guess. But not for a long, long while with what I’ve got to do. Right now I’m as free as the birds. But the point is: You can get a cockeyed slant on things from the spot I’m in if you don’t watch out.

“But then,” reflected Bob, “I come on this lot and I walk around and see what’s here, what it’s really ail about. Big things going on all around. The greatest talent, brains and energy making important entertainment for millions of people all over the world. And I’m a part of it!

“That’s the really wonderful thing that’s happened. to me. That’s what I’ve got to prove I’m up to. Say,” he choked it off, “can I give you a lift to your car? Got to dress, eat and catch a show.”

We climbed into Bob’s new Mercury, with all the gadgets, black finish outside, red leather inside. Bob gunned it confidently with a last loving look at the place he’d rather be than anywhere else, despite all you might hear to the contrary. He didn’t seem so worried any more. “So long,” he waved when we reached the gate. “Let’s have a drink sometime and maybe another talk.”

The gateman took my pass. “Been with Bob Wagner? A mighty fine boy,” he said. “Going to be a big man around here one of these days.”

I nodded. Why not? It’s not exactly impossible.

THE END

—BY JACK WADE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1954

No Comments