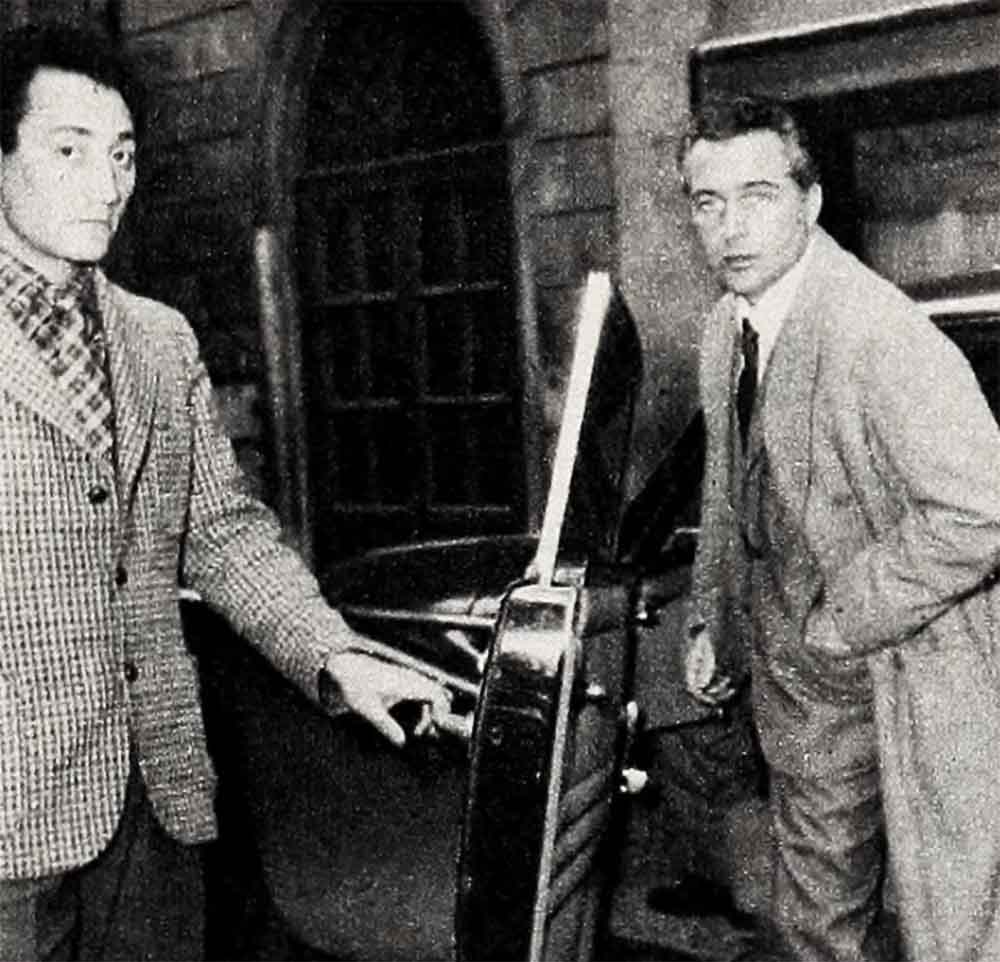

Rossano Brazzi Leaves His Heart In Rome

The bride and groom kneeling solemnly and reverently before the ancient Italian altar of San Iacopini Church in Florence were not young. A casual observer might even have wondered how the handsome man, with his electric-blue eyes, lean jaw and striking gray hair, had escaped the marital knot before this.

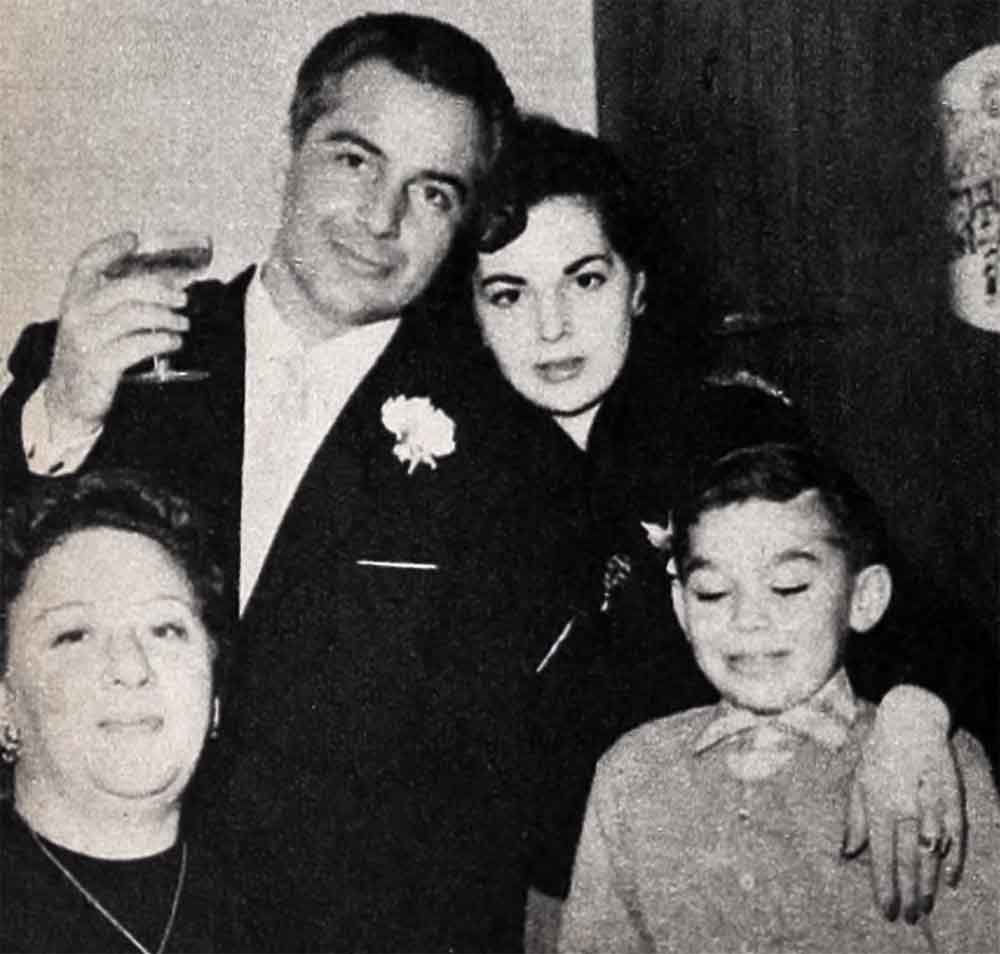

As the couple, followed by family and friends, emerged arm in arm from the somber shadows of the medieval church into the bright Florentine sunshine, cheers of “Auguri, Auguri, Brazzi!” (meaning “Good luck”) greeted them from the crowd bunched outside.

AUDIO BOOK

Rossano Brazzi grinned happily and waved at his hometown fans, then he and his wife climbed into their car and drove slowly along the banks of the tawny Arno River to his mother’s home. There, in the warm, intimate atmosphere of a tightly woven Italian family circle, Rossano and Lidia Brazzi celebrated a momentous day.

This event took place a few months ago. On that day, the fifteenth anniversary of their marriage, Rossano and Lidia were married for the second time, duplicating the marital services which had first united them fifteen years before in Rome. Then, young, stubborn, and very much in love, they had ignored the objections of both their families and had married without parental consent.

No one from their families came to that first wedding ceremony, and the young couple began their married life in the lonely gloom of parental disapproval.

How different was this second ceremony! The Pope himself had sent the Brazzis a special benediction. Everyone from both their families, including Rossano’s widowed mother, his brother and sister, Lidia’s parents, and all their in-laws—nieces, nephews, aunts and uncles—were there to drink to their health and wish them well.

“My wife’s family, who are titled, first objected to me because I didn’t come from nobility,” explains Rossano. “They thought Lidia should have married the stuffy lawyer she was engaged to before I came along.”

“Rossano’s family thought an early marriage might hurt his career. Besides, everyone thought we were both too young and headstrong,” is Lidia Brazzi’s explanation.

Anyway, that was all in the turbulent past, and both families now enjoy a close relationship. In fact, Lidia’s parents make the Brazzi apartment in Rome their winter headquarters.

The span of fifteen years, which had witnessed the shift in family sentiments, had also marked a few changes in Rossano’s professional life. After more than a decade of success in Italy, this veteran of 80 pictures and numerous plays has found himself, at the age of 39, suddenly “discovered” by Hollywood as a romantic screen lover, the epitome of continental charm and Latin gallantry.

Hundreds of perfumed letters, throbbing with daring declarations of love and longing, pour in daily at Rossano’s apartment in Rome. Most of them come from America. One woman, the mother of three children, was inspired to pen him the following verse: “God made wine, God made cheese, God made Rossano for me to squeeze.” Another sent him a solid gold watch.

When Rossano was in New York last year for the premiere of “Summertime,” a magnificent Cadillac was delivered to his hotel, with a note—and five pictures of herself—from a fan living in Chicago, who invited him to visit her in the Windy City. The invitation was generously, if reluctantly, extended to his wife also. Twenty fans in Japan have asked Rossano to come to their country—at their expense—and spend a day in each one’s home.

Rossano reacts with gratitude but caution to all these overtures and demonstrations from his fans. “Life would mean very little, if there were no women,” he purrs. “I admit I have a great liking for them.” Then he wisely adds, “But remember, I have been happily married for fifteen years, and each year I think I love my wife more.”

The roving, caressing eye, which has become the Brazzi trademark, goes well with his movie cloak of Casanova, but off-screen Rossano is a deeply devoted husband. His wife, Lidia, a buxom, jovial, blue-eyed bundle of energy and charm, is the solid foundation of strength and understanding on which Rossano has built his life. Although their relationship is occasionally beset by raging arguments, for each has a violent temper, Rossano could not visualize life without Lidia.

“Of all the women I have met, both on the screen and off,” he says, “I still think my wife is the most interesting.”

In addition to her witty and bright personality, Lidia Brazzi has a rare understanding of the demands of Rossano’s career. She never interferes with his plans, never questions his appointments, is always there when he needs her. Sometimes, however, she feels that her presence may be a drawback in his professional life, so she keeps in the background as much as possible. This is at her own insistence.

“I have been to a studio to watch Rossano work only once, and that was enough for me,” she says, her eyes twinkling in good humor. “It was several years ago, here in Rome, and Rossano was making a picture with Alida Valli. As I started to go on the set, an assistant director approached me and, with an embarrassed air, explained that Rossano was in the midst of a love scene with Miss Valli. It had never quite hit me with such violence before that making love to other women was a part of Rossano’s work. I smiled and whispered to the assistant, ‘Don’t tell him that I’ve come here. I’ll wait for him in the car.’ I’ve never visited a set since.”

We were sitting in the tastefully furnished Brazzi apartment in Rome. While chatting fluently in her gently accented English, Lidia kept one ear cocked toward the door in the event she was needed by Rossano, who was resting after a slight case of flu. She had just recovered from a serious bout of the same sickness, in time to take care of Rossano.

“It is very easy to be Rossano’s wife,” Lidia said gaily. “He is such a good boy. We have many fights, of course, but it is impossible to stay angry with him very long. When he screams, sometimes I scream louder than he does.

“When he sulks, I am quiet. I say nothing. Once we had a terrible quarrel. We had to stop it because we were expecting guests for lunch. At the table, I served everyone except Rossano. I spoke to everyone, but not a word to him. I kept this up for two days. I laughed and sang, as I always do around the house, but I never addressed a word to him.

“Finally he couldn’t stand it any longer. ‘Why don’t you talk to me?’ he pleaded like a little boy. How could I stay angry with him?” she smiled.

Lidia learned very early in their married life that generous portions of trust and confidence are the basic ingredients for a happy marriage. Rossano has been attractive to women ever since he was eight and his father boxed his ears for flirting with a girl of twenty. Lidia soon realized that, if she was not going to be haunted by doubts and fears every minute he was out of her sight, she had to have faith in him.

“When Rossano goes off to work, I say, ‘Goodbye, take care of yourself, work hard.’ I never ask him what time he will be home; I don’t call the studio if he isn’t back at his normal time; I don’t try to control him. I realize that actors often have obligations outside their home. Sometimes he says, ‘I’ll be home about midnight.’ ‘Okay,’ I say.

“But maybe he comes earlier than he had planned. During our entire married life, I have never had the sensation that he was involved with another woman.”

Sometimes, to tease him, Lidia says, “Poor Rossano, poor man, don’t you wish you were free?”

Then Rossano gets angry and cries, “Don’t say such things! I’m happy. I have everything I want.”

Lidia has put on about eighty pounds since her marriage, but she is not self-conscious about her weight. She loves to dance and is as light as a feather on her feet. Not in defiance, but because she likes them, she usually wears low-cut dresses, which emphasize her ample bosom. Instead of skipping over the subject, she jokes about her stoutness. When Rossano occasionally chides her and suggests that she reduce, she answers indignantly, “Why should I? You are the beauty of the family, not me. Leave me alone.”

Actually, Lidia has made several super-human efforts to cut down her weight, and she is a delicate eater. As she says, “This is my nature, what can I do?”

But not for an instant does she feel self-conscious or submerged when in a group. She overcomes her lack of sveltness with her charm and personality!

Lidia usually accompanies Rossano on his film engagements outside of Rome. The rare times they take a plane, they travel together.

The only time they have ever been apart for any length of time was last year during Rossano’s personal appearance tour in America for the opening of “Summertime.”

Forty-eight days,” Lidia sighed. “It was our longest separation since our marriage.” During that trip, Rossano phoned Lidia in Rome every night. He would recount his adventures in the various cities he I had visited. He went to tea with ten newspaperwomen in Boston, and before he knew it, was accompanying them on a night club tour that lasted until four in the morning. But before he hopped into bed, he called Lidia to tell her all about it.

Lidia is Rossano’s severest critic. She analyzes all his performances with a discerning eye, and admits ruefully that he has made more bad movies than good ones, “Summertime” is still her favorite one. She knew Rossano was good, but never expected him to be the sensation he became. Rossano, too, had been somewhat amazed at his success.

“They have seen nothing yet,” he says. “I shall surprise everyone with my next pictures. I am going to do much better.”

Rossano’s assurance in himself is not based on over-confidence, but as he puts it, “I’ve found the gimmick. I know now what is expected of me—a continental manner and accent, with the emphasis on sex appeal.

“I cannot compete with American performers as an actor,” he adds. “There is the language difficulty. I speak English, of course, but to interpret a role in a creative manner, one must understand the nuance of each word. That I cannot do, so I must express myself with my hands and with my eyes, in my own fashion.”

It is perfectly natural that Rossano’s satisfaction over his recent good fortunes is tinged with a note of triumph. “I wish it had happened years ago,” he says, “and it could have so easily. When I first went to Hollywood, in 1949, I wanted to play romantic roles, but no producer thought I could be convincing.”

Rossano almost shudders in horror when he thinks of the year he and Lidia spent in Hollywood. He prefers to forget about it, He thought it would be the big break of his life, but it proved to be nothing more than heartbreaking.

David Selznick, impressed by Rossano’s reputation as the Latin Errol Flynn (“I usually arrived in my co-star’s arms after leaping over high walls and ramparts”), brought him to Hollywood in 1949.

“For a long time,” Rossano recalls, “I sat around and did nothing. There was nothing for me at the studio, so finally Selznick lent me to M-G-M. I must explain that my English was not very good in those days. They handed me a script and a teacher to coach me in my lines. I learned them and repeated them mechanically, but I had no idea what I was saying.

“I began to get suspicious that all was not well when make-up men began trying on wigs and beards. ‘What are they doing to me?’ I said to myself. ‘Did I come to America to play the part of an old man?’ ”

The picture was already rolling when Rossano realized that he had been cast as Professor Bhaer, the middle-aged German music teacher in the re-make of “Little Women.” But it was too late. All he could do was heartily agree with Selznick, who later said to an M-G-M executive, “I lent you Brazzi, but without beard or glasses.”

Although Rossano had a disillusioning professional experience in Hollywood, both he and Lidia fell in love with the community and its way of life. They made many friends, and it was not unusual for them to entertain as many as seventy-five people several times a week at mammoth spaghetti dinners.

But even their friends and a busy social life could not compensate for Rossano’s unhappiness over his work. Lidia realized this and cheerfully endorsed his decision to ask for his release. Refusing the title role in “The Life of Valentino,” he sailed home, a sad and disillusioned man.

After my return to Italy, I had a rough time getting parts,” says Rossano. “Everyone thought I had flopped in Hollywood and that that was the reason I had come home. They figured if Hollywood didn’t want me, they wanted no part of me either.”

So he tried his hand at producing, but he lost most of his personal fortune in two ill-fated films. Then, gradually, he began to regain his former position as Italy’s top male star. It was at this time that Jean Negulesco convinced him to accept the role of the penniless lawyer in “Three Coins in the Fountain.”

“It was a small part,” says Rossano, “and I realized it. I had already refused several Hollywood pictures because I didn’t want to be burned again. But I felt that this one was the second chance I had been hoping for.”

Rossano had no sooner finished “Three Coins” when he was offered the part of the count in “The Barefoot Contessa.” Again he hesitated. “The physical handicap of the character was an unattractive factor,” he explains. “Despite his charm, he was certainly not a likable person. But it was a challenge.”

The dent Rossano made in the hearts of the female movie-going public is proof of how well he met the challenge. The nightmare of his shaggy-beard days in Hollywood was fading into a fuzzy memory, and with “Summertime” he was definitely established as one of the leading romantic heart throbs of the day.

Now, Rossano has a contract with Universal-International, which provides for three pictures in the next three years, and gives him the right to outside commitments. Recently, he finished the English production (for United Artists release) of Graham Greene’s “Losers Take All.” It’s a comedy set in Monte Carlo, and also stars Glynis Johns. This summer, he will make his first U-I film, “Interlude.”

Rossano and Lidia will have only a few weeks’ vacation in their favorite resort spot in the south of Italy before he is due in London for the lead opposite Joan Crawford in Columbia’s “Esther Costello.”

That will bring him well into 1957. By then, Rossano hopes, a shooting date will have been set for “South Pacific.” He is Rodgers and Hammerstein’s favorite candidate for the male lead, and he makes no bones about his fervent desire to play it. Rossano has a fine trained baritone voice, but he’s never had a chance to sing on the screen. He is now studying under Rome’s finest singing teacher, who was so impressed with his voice that he offered Rossano a month’s lessons free of charge. “You can put Sinatra to shame,” the professor told him recently.

Rossano’s success and newly awakened international fame has not changed his way of living. His small apartment on Rome’s swank Via Sistina, is still crowded with relatives and friends who drop in at all times of the day and evening.

The Brazzis are warm and hospitable hosts, and they rarely sit down to lunch without sharing it with some member of the family. The only concession they are making to Rossano’s new contract is a Hollywood-type villa, complete with tennis court and swimming pool, which they are building on the outskirts of Rome. And, for what promises to be frequent visits to Hollywood, Rossano is planning to buy a home in Beverly Hills. But he will always make his permanent residence in the Italian capital, and he invests his savings in property and factories in Florence.

“I do not forget that I am Italian,” he says.

Rossano, the son of a wealthy leather manufacturer, was born in the ancient university city of Bologna. When he was very young, his family moved to Florence, and there he grew up with his younger brother, Oscar, and his baby sister, Franca.

At an early age, he decided to become a lawyer, but he was equally as interested in amateur dramatics and sports. At thirteen, he toured Italy in a musical comedy; at seventeen, he was amateur boxing champion of Italy, as well as a champion tennis player. At eighteen, while a student at the San Marco University at Florence (where he received his law doctorate), he won a prize as the best actor.

It was about this time that he met Lidia Bertolini, member of an aristocratic Florentine family. They were both students at the university, Rossano in law, Lidia in literature, but their first glimpse of each other was at a drama school they were attending.

One day in class, Lidia’s girlfriend nudged her and whispered, “There’s Brazzi. Isn’t he handsome?”

Lidia recalls today that she wasn’t at all impressed. Later, she saw him in a school play and thought he did a fine job. She went backstage and told him so.

They didn’t meet again until several weeks later. Lidia was traveling by train to a village near Florence where one of the school plays was to be presented. He girlfriend pointed to Rossano who was standing in the corridor, watching Lidia intently. Lidia remembers that he wore a high-necked Russian blouse and looked very dashing, but pretending not to be interested, she commented to her friend, “This one has a stupid face.”

She saw Rossano again at the hotel where the school troupe was staying. He was frantically going through his suitcase looking for a shirt. “He looked so miserable, and the suitcase was in such a mess,” Lidia recalls today. “His mother hadn’t had time to pack it for him, and he had done it himself. We began to talk and we talked the rest of the evening.”

“We must get married,” Rossano said almost immediately. Lidia was engaged at the time, but she broke it off. They went together for two years, in spite of constant family opposition, before they decided to go off to Rome and get married.

“You can change your mind,” Lidia used to tell Rossano at regular intervals up until the day of their wedding. “It’s not too late. You might be sorry one day.”

“I will never regret it,” Rossano said at the time, and he still says it today.

Rossano’s parents didn’t approve of his getting married, but they were even more opposed to his abandoning law in favor of the stage. He spent three months dividing his time between the court room and rehearsal halls, until one day he decided to concentrate on swaying audiences, rather than juries, with his rich voice.

His first important stage role was in the Italian version of “Strange Interlude,” and he received fine notices. For two years, he and Lidia played in the same company.

Rossano was seriously interested in breaking into movies, but an unsuccessful screen test had left him discouraged. One night he and Lidia were sitting in the Cafe Castellino, a theatrical hangout, when a friend came over to their table.

“Hey, Rossano, there’s a big movie director over there. He wants to talk to you.” Rossano got up and went over to talk to him. After a few minutes he came back and said glumly to Lidia, “It’s for you.”

Lidia didn’t want to take the part the director was offering her. She hated acting; all she wanted to do was stay at home and take care of Rossano, but he urged her. “We need the money,” he reasoned.

Lidia worked for one day in a bit role. It was enough to convince her that she wanted no part of movies. Sometimes now, when Rossano returns home from the studio, tired and listless, and Lidia insists upon going out, saying, “Oh, you can’t be that tired,” Rossano reminds her of that day. “Don’t you remember how weary you were, how you said your feet felt as if they had been glued to your shoes? Well, that’s how I feel.” Then, of course, she relents. Rossano received his first real break in a picture, called, “The Trial and Death of Socrates.” After that it was easy going, and he became the most sought-after male star in Italy. Then Selznick saw him in “Black Eagle” and signed him.

His first trip to Hollywood may have proved a disillusioning experience in many ways, but it was there that Lidia learned how to cook. “I had nothing else to do all day,” she says, “so I practiced different Italian dishes.”

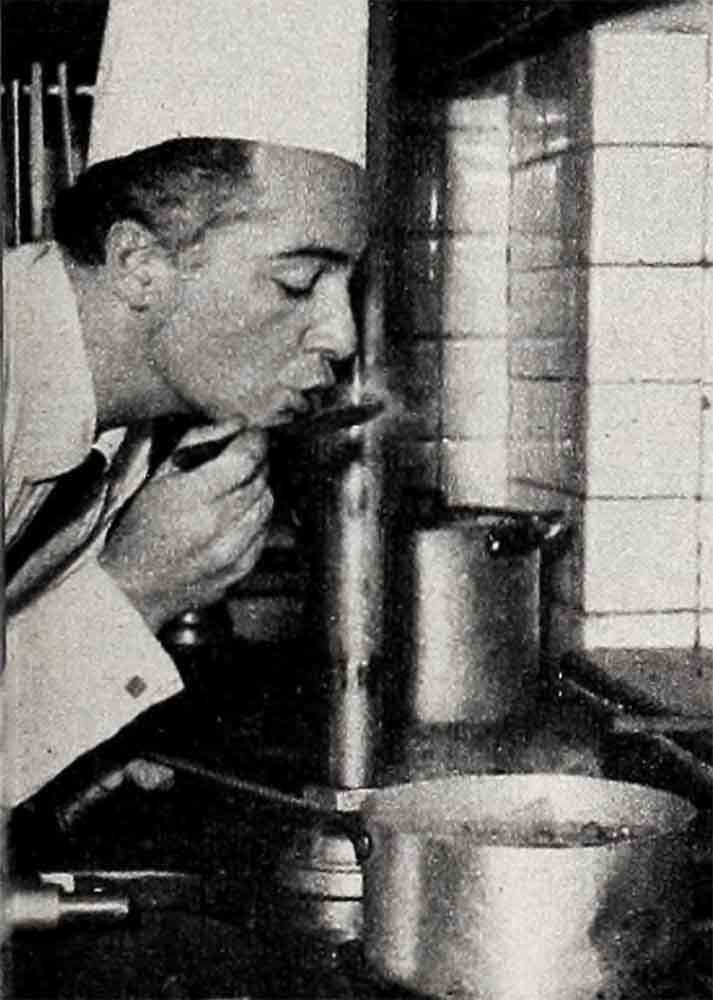

Lidia is Rossano’s favorite cook, and the instant he enters their apartment he can tell by the aromas coming from the kitchen whether Lidia has cooked the day’s meal herself. The dish he prefers above all is Lidia’s own recipe for Tortinelli, a type of ravioli, made with meat and cheese, and served with broth. Like most Italians, Rossano has a keen interest in food, and is an expert cook himself. He recently invented a sauce for chicken, and a well-known Roman restaurant is featuring it on its menu as Poletto a la Brazzi.

Rossano is essentially a homebody, and he likes nothing better than an evening at home playing bridge or canasta with friends. “Lidia is a better player than I am,” he says, “but I will never admit it to her.” But Lidia loves to go out, so when Rossano is not working, the Brazzis are faithful first-nighters and frequent night-clubbbers.

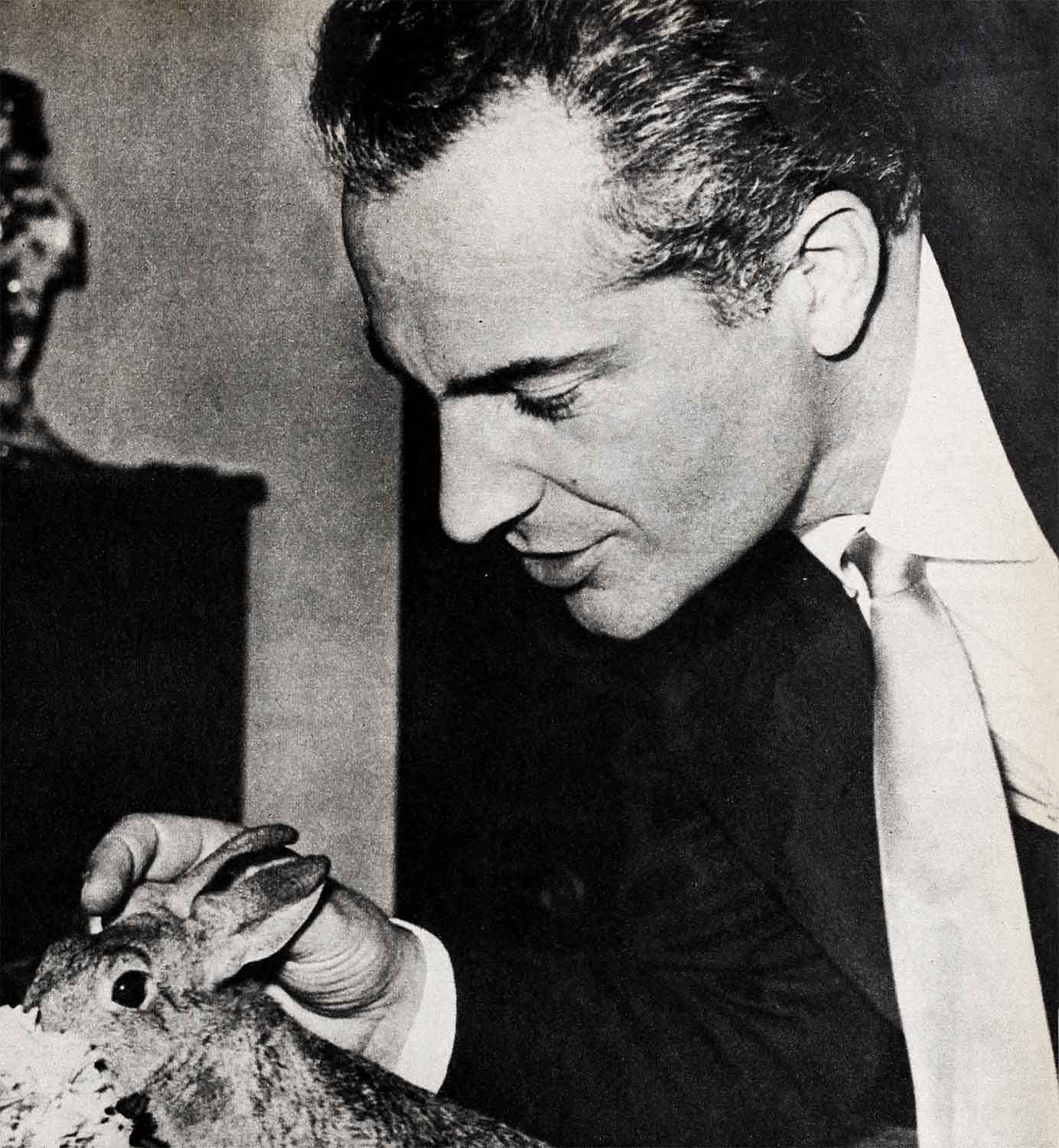

The couple’s deepest sorrow is that they have no children, and they pour their love and affection on animals of all kinds. They have two French poodles, which they bought in Hollywood, and a Spanish Bredow. A less conventional member of the family is their little rabbit, which Rossano acquired three years ago, while on location in Spain. He had just put his luncheon basket into his car when he saw a gray streak headed for the basket. He put his coat over it, wondering what kind of creature, he had captured. It was a wild rabbit, and it has been a member of the Brazzi family ever since.

Perhaps the main reason for Rossano’s appeal to women, both on screen and off, is his suave virility. He can kiss a woman’s hand with elegance, but he is also a formidable opponent in a boxing ring. He is an expert skier—he and Lidia spend most winter weekends at the ski resort of Terminillo, an hour’s drive from Rome—a keen soccer and tennis fan, and is passionately interested in racing. “I don’t drive any more,” he says. “I drive too fast, and am much too nervous.”

Rossano’s interest in sports does not prevent him from also being a serious student of languages and music. He knows Latin and Greek, as well as five modern tongues. He adds to his vast record collection by exchanging, with his American fans, books on Italian art for the newest discs. In modern music, George Gershwin is his idol.

Although he loves his work and is restless when he has nothing to do, Rossano wants to limit his pictures to two a year. As Lidia says, “There must be time to enjoy life. Money—after all, what is it? If you have enough to do what you want, that is all that is important. I am no happier now that Rossano can give me a mink coat and diamonds than I was when he was earning 100 lire a day.”

Lidia stopped suddenly in the midst of her thoughts and glanced toward the bedroom door. It opened slowly, and Rossano, fetchingly handsome in a Scotch plaid bathrobe, stood there rubbing his eyes.

“Ah, the beauty is up,” Lidia smiled at him affectionately, and began humming a song happily. Her whole attitude changed now that Rossano was in her presence. “Cicci, how is the cold?” she asked him anxiously. (“Cicci,” an untranslatable term used, between lovers, is Rossano’s and Lidia’s nickname for each other.)

“Better, much better,” Rossano answered, stifling a sneeze.

“Poor boy,” Lidia sighed, looking at her husband sympathetically. Then, her words changed as rapidly as her thoughts, and she said, “Now, what is more correct in English for Noze di Rame, fifteenth wedding anniversary—is it copper or brass?”

Before I had a chance to answer, she shook her finger playfully at her husband, and said, “If only he would speak English with me, I wouldn’t have to ask these things.”

“If I speak English with you, I will forget how to speak it properly,” Rossano answered with dignity.

“Ah,” said Lidia, “I will look it up in the dictionary. But, no, why should I bother? Who cares anyway for our fifteenth wedding anniversary?”

“What do you mean?” cried Rossano. “I care, that’s who cares!”

It was obvious tiny clouds were gathering for a minor storm in the Brazzi household. It was time for me to go.

Rossano said goodbye warmly and prudently avoided the drafty hall. Despite my vehement protests about the cold, Lidia insisted upon accompanying me to the outside door. From inside came wafts of sound which resembled Rossano’s voice.

“Lidia, you just got out of bed with the flu. Don’t stay in that drafty hall! You will catch cold again, and I’m the one who has to pay the doctor bills.” The voice got fainter and fainter. Lidia glanced at me, winked slyly, and said with a happy smile, “Let him scream.”

As the elevator drifted slowly down, I could hear the strains of what had now become a duet, without music. All was well in the Brazzi household.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1956

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments