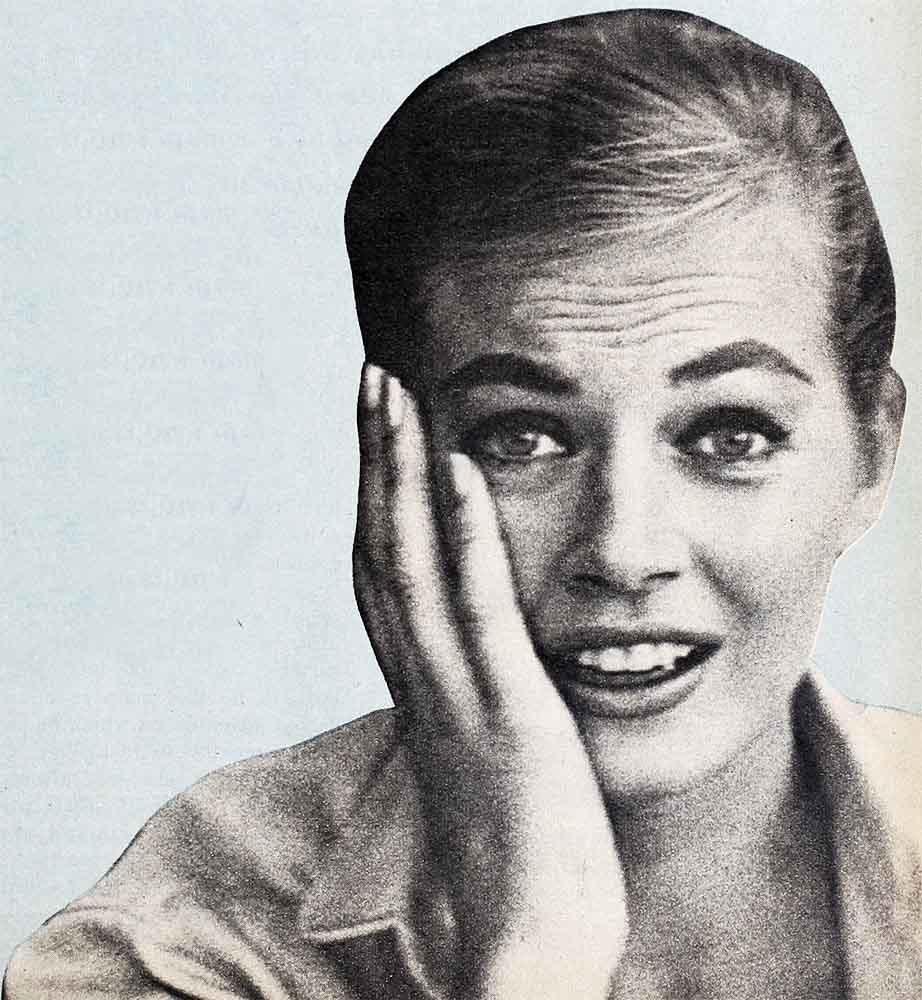

Red Hot Iceberg

Imagine a volcano erupting in the middle of a frosty iceberg. Imagine a South Seas island suddenly blanketed with snow. Imagine the most bewildering and unpredictable female this side of the Arctic Circle and you have a fair picture of Sweden’s latest contribution to the movie world.

“I do exactly what I like,” stated Anita Ekberg. We were lunching at an English tavern near the Warwick studio, Anita, her new husband, who is Anthony Steel, and I. To prove her statement, Anita passed up the Scotch everybody else was taking and ordered tomato juice.

“Why should I drink when I don’t feel like it?” she demanded, facing me squarely. “Often, I go to a cocktail party and everyone is drinking. I don’t want a drink. So I ask for a glass of milk.”

“You don’t feel you’re offending the hostess?” I inquired.

“Why?” Anita promptly parried. “Haven’t I been invited to enjoy myself? Why shouldn’t I do what I please?”

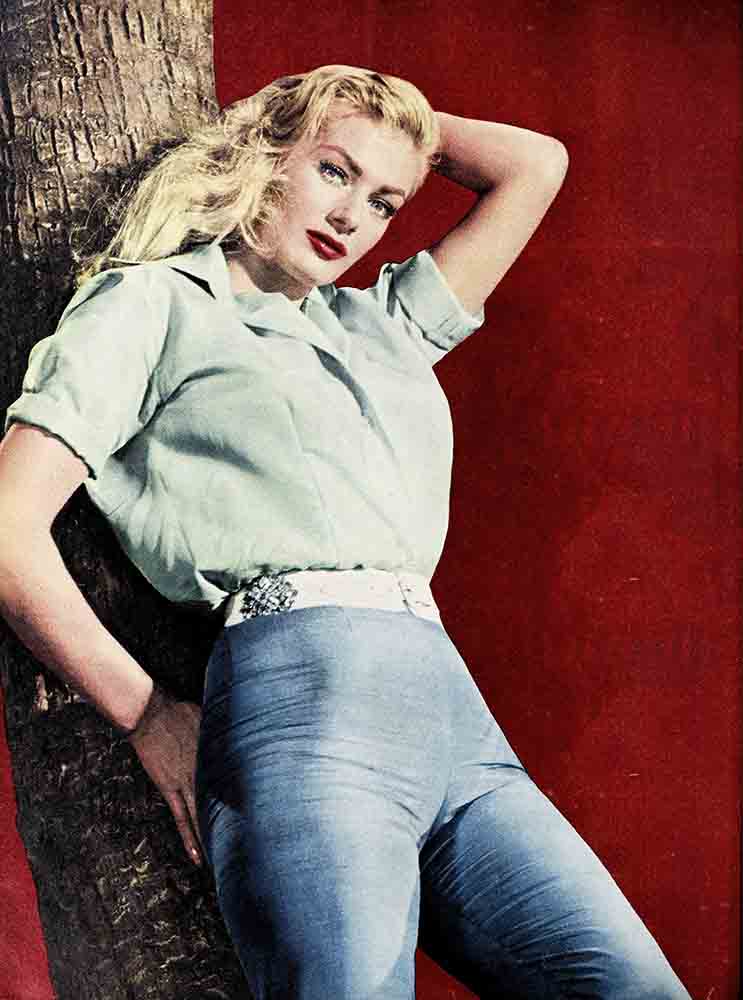

Anita sat before me, looking very self-assured, a typical Scandinavian trait. She was wearing a powder-blue silk dress, which clung to her well-aligned figure like a wet stocking. Her skin was smooth and white, as a Nordic beauty’s should be. You could see only her penciled eyebrows above the sunglasses she was sporting, although it was October in England and the sky was gray. Her husband—polite, proper and British—was looking a little nervous. Obviously he had had previous experience with his bluntly outspoken wife. He handed her a menu, his motive plainly to get her to change the subject. I helped by inquiring about their marriage.

AUDIO BOOK

“We were married seven months ago,” said dark-haired Tony. “We had the ceremony and our honeymoon in Italy. Of course, Anita was working on her picture, ‘Interpol,’ most of the time. But we had long weekends to ourselves.”

Anita decided abruptly, as she does everything, to remove the sunglasses. Her eyes were as clear and blue as the Baltic. She leaned forward to join in the conversation. “When we were in Genoa, the reporters and photographers were furious with us,” she declared. “They complained we were avoiding them. We never went downstairs to the dining room or the bar. We never went to restaurants or night clubs.” Anita gave me that self-assured look again. “But why should we? I was tired. I had been working all day. All I wanted was to have a quiet dinner with my husband in our suite. I don’t care to spend an evening in a bar, drinking with a lot of dull people I may never see again.”

This Ekberg woman was turning out to be quite a talker. Scarcely pausing for breath, she rattled on, “I can’t stand boring people. They make me so nervous I could scream or throw china. Why, just the other night, Tony and I were dining out. A man we didn’t even know walked up to our table and had the nerve to sit down and start a conversation. I just told him, ‘Will you please get up and leave?’”

Lunch was being served and we drifted into a discussion of the young couple’s mutual acquaintances. “I try to be nice to Tony’s friends,” remarked Anita. “I realize he has known them for years and if he wants to see them I feel there’s a reason. So,” she concluded matter-of-factly, “I put up with them.”

But how about her friends?

“I never did have many close girlfriends,” Anita answered. “Today, I don’t have any. That is, no one whom I keep in touch with. My old friends in Sweden or America understand. Marriage hasn’t changed me. I’ve always been like this.”

Anita said that when she first came to Hollywood four years ago, she had a few girlfriends. Sometimes, she and one of her chums would meet at a restaurant for lunch. They would chat and laugh away a good hour. “Then all of a sudden,” Anita recalled, “I would get up from the table. I can’t explain it. But I just wanted to go. I’d had enough.”

This is the characteristic best described as moodiness. Anita can change, in a split second, from a jolly companion to a brooding, silent cake of ice. Aware of this peculiarity, she has learned to make quick exits the moment the mood strikes.

“Sometimes, I just have to get away— far away from everybody and everything,” she continued. “In California, I would get into my car and start to drive. all by myself. I never knew where I was going or how long I would stay out. If I saw a country road that looked interesting, I would try it. Maybe I came home in time for dinner, maybe at midnight.”

But now that she’s married, can Anita Ekberg still do exactly as she pleases?

The blonde, Swedish volcano stared thoughtfully. “I try to compromise,” she observed at last. “Today, I say to Tony, I’d like to take a ride in the country. Will you drive me?’”

“And I always do,” smiled Tony.

In the London papers recently there had been some nasty gossip about Anita and Tony slapping each other’s faces in public. It was time to ask about this.

Tony was the first one to speak up. “It really wasn’t anything,” he contended, with typical glibness. “Just bad press.”

But leave it to Anita to blast out with the truth. “I have a terrible temper,” she openly admitted. “And so has Tony. Of course, we clash! We have a good, loud argument—in public or in private. But then, after it’s all over, we laugh. Ten minutes later, we’ve forgotten about it.

“Family fights are nothing,” she went on. “I’ve heard my mother and father arguing fiercely. When I was a child, I sometimes thought the roof was going to blow off. But now I know their fights weren’t important. They were just letting off steam. The proof is that my mother and father have been” happily married for thirty-five years.”

That naturally led into a discussion of marriage. People as explosive as Ekberg are not usually considered good marriage risks. But suddenly Anita was looking very demure and starry-eyed. She said this was her first marriage and Tony’s second. She related, a little breathlessly, that she had anticipated for a long time the happy day when she would be someone’s wife. “Every girl dreams of having a husband,” she said. “Cooking for two instead of one, sorting soiled socks from soiled shirts and managing a household.”

“My wife’s an excellent cook,” Tony mentioned at this point. “We may go to the finest restaurant, where we are served the most elaborate dishes, and yet they never taste as good as Anita’s cooking.”

“I cook by intuition,” smiled Ekberg. “I remember watching my mother in the kitchen. She never used recipes. Today, when I prepare a meal, I throw in whatever herbs or spices I want. I enjoy cooking. The only thing I hate is washing dishes. In California, my maid comes only on weekdays. I do most of my entertaining Saturday and Sunday. By Monday, there’s not a clean fork left in the house!”

Anita stopped and consulted the menu. The fruit cup a la mode sounded most enticing to her. I found myself marveling that anyone so perfectly proportioned could eat with such abandon. I still didn’t know Ekberg. She had changed her mind long before the dessert appeared.

Meanwhile, we wanted to hear more about Mrs. Anthony Steel.

“I love it!” Anita beamed. “The first few weeks, I used to open the closet doors and just stand there, looking at Tony’s suits. They made me feel warm and safe. And Tony is so neat. I marvel at how everything is hung up carefully.”

“Army training,” Tony put in.

“But I’m not neat,” confessed Anita. “When I come home, I take off my clothes and throw them around the room as I go. Of course, now that I have Tony, I try to correct myself. But Tony is so meticulous, he’s always ahead of me. I may leave a sweater on a chair, because I haven’t decided whether to wear it or not. By the time I’ve made up my mind, the sweater is gone. Tony has found it and tucked it away in a drawer.”

Anita said she loves Hollywood, even though they gave her a pretty rough time when she first went out there. You see, Anita, native of Malmo, Sweden, began her career as a model in her own country. While still a teenager, she won a “Miss Sweden” beauty contest and a trip to California. But once there Anita failed to land the movie contract on which she had set her sights. She went home, slightly embittered. But not for long. That’s that Nordic stubbornness. Never say die! In less than a year, she turned around and struck out for Hollywood again.

“I nearly starved to death,” she recalled. “There are a lot of blondes in Hollywood.” Anita settled for modeling and became the curvy subject for hundreds of pin-up pictures. Finally, the breaks came. Two small movie roles. And in 1955, a leading part in “War and Peace.” In 1956, at the age of twenty-four, Anita won her first starring vehicle in “Interpol,” with Michael Wilding and Victor Mature.

“I’m going to be a good actress and a famous one,” Anita predicted, without the slightest hesitation. “This is only the beginning’. I have sex appeal and I have talent. Tony and I plan to work in pictures together. We’re both going to be tremendous successes.”

Tony, who has done very well so far as a British star, smiled quietly. He took a more modest attitude toward their mutual efforts. “We rehearse scenes together now,” he remarked. “It helps Anita in ‘Interpol.’ And when I’m working and she’s not, she’ll help me, cueing me on lines. It should be a fine combination of careers and marriage.”

Without any warning, Anita suddenly stiffened. Her eyes were blazing, the black pupils in the blue orbits enlarging rapidly, like an angry cat’s. “Fine. It people would just leave us alone!” she exploded.

I gave her a questioning look.

“Reporters and columnists,” she stormed away. “They will pick up anything Tony and I do and try to make the worst out of it. Our life is not all sensational. We are human beings. We have problems. Just leave us alone and we’ll solve them.”

In the next instant, Anita Ekberg was on her feet. She hadn’t touched the fruit cup. “I have a two o’clock call,” she announced abruptly. Then, just as abruptly, she was smiling, looking as sweet and gentle as a kitten. “It you want to come over to the set after you’ve had your coffee,” she informed me, “I’ll be happy to talk some more.”

I most certainly did want to talk some more! Why had she flared up like that? What on earth were her problems? “I’ll be there in a few minutes,” I assured her.

Fifteen minutes later, Anita Ekberg and I were siting on directors’ chairs in a dimly-lighted corner of the “Interpol” set. Oddly enough, we immediately began chatting like two long-separated school chums. Why the quick change, I wondered? In the tavern, Ekberg had behaved like a Geiger counter, hopping over a uranium patch. Now, she was so relaxed and friendly, I hardly recognized her.

Then it dawned. It takes a woman to know one. The answer was simple: Anita Ekberg was alone, now. Tony had gone back to town. Here in the shadows of sets, props and cables, she was just Anita, the plain little girl from a plain little Swedish town. She was not Mrs. Anthony Steel, talking big to impress, intrigue and excite her man.

“Yes, we have problems,” Anita conceded. “What new marriage doesn’t? I like to watch television. Tony says it’s boring.”

“Who wins?” I asked.

“I do,” she chuckled. “And then,” she continued, “there’s the question of how I should wear my hair. I like it up. Tony likes it down. Once in a while,” she winked, “I let it down.”

Like two females will, we got off on the subject of clothes, and Anita said she prefers pastel shades, but picks strong colors for formals. “I have a mania for buying things,” she confessed. “I can’t pass a store window without going in.

“And I like to experiment, as well. In Rome, I bought a real Cardinal’s hat—the black kind with the shallow crown and the big, round brim. I wound a cerise chiffon scarf around it. Everybody thought it was going to look hideous. But it turned out a sensation!”

Does Tony like her selections?

“Oh, yes!” Anita exclaimed. She drew her chair closer and confided enthusiastically, “And he often brings home wonderful pieces of jewelry to go with my new clothes.”

As for Tony’s clothes, she doesn’t interfere. “He’s a perfect dresser,” she stated. “And you know how all the girls flipped for him before I got him. That’s why it’s so wonderful to see how considerate and devoted he is.”

The topic was getting a little ickie, so we went back to problems. Anita began thinking hard. “The other night, I got home from the studio late and I was so tired, I just tell into bed,” she remarked finally. “Tony was in the room, writing a letter. all I said to him was, ‘Hello, darling. Kiss me good night!’ That’s a problem, I guess. But,” she added philosophically, “there’s always tomorrow. . . .”

Then there actually weren’t any serious problems?

Anita shook her head naughtily. “No. . .”

“What are you really like, Anita?” I asked.

“I’m hot and I’m cold,” she answered promptly. “I’ve had struggles and I’ve cried. I’ve been ecstatically happy and I’ve laughed. I’ve spent miserable, lonely days and nights and I’ve been depressed in a crowd. I’m ambitious and I believe in myself.” She stopped suddenly. “Why do you ask so many questions?”

“Because I want to know a lot about you.”

She gave me that frank, direct look. “I believe,” she declared significantly, “you know too much already.”

That obviously was a signal to leave. But as I rose, I caught a strange expression on Anita’s face.

“Oh,” she was saying, almost plaintively, “must you go so soon?”

Unpredictable Anita Ekberg!

THE END

YOU’LL ENJOY: Anita Ekberg in Columbia’s “Interpol.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1957

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments