Nobody Asked Him—Montgomery Clift

“Monty? You can set your watch by his word,” a friend had said. Well, now was the hour. Just then the phone rang.

“Hello!” It was Monty’s voice, warm and merry. “Say, how do I get up there?”

How did he arrive at my place, he meant: He d rented a car. but he still didn’t know his way around Hollywood too well. He was still a New Yorker in town. And he understood there were those who had gone into the Hollywood hills and were yet to be heard from.

This was when I first really knew that I was about to meet —finally—the real Montgomery Clift. This, after I’d spent all of one freezing night on location at the Columbia ranch with the company of “From Here to Eternity,” sweating out how to get to him. It was a night through which I’d alternately sweated and frozen and drunk coffee and waited, waited for Montgomery Clift to put down Prewitt and talk to me. Later I had come to realize that for Monty to put down Prewitt or any other character in whom he’s currently embodied is psychologically impossible.

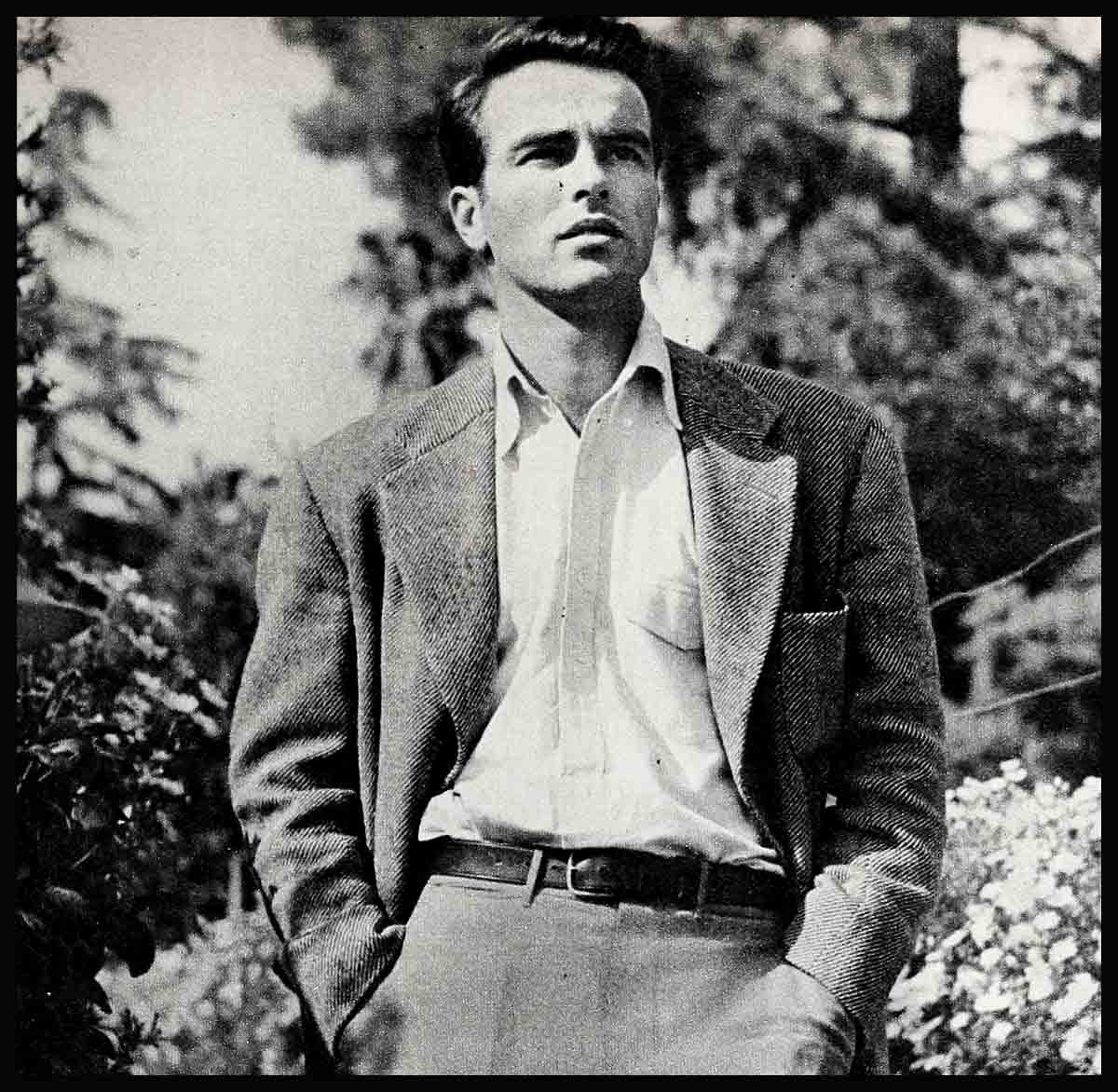

So I gave the exact details for reaching my house. And not long afterward he zoomed up the hill in a blue Chevrolet convertible, parked it, and came as directed up the back stairs. He was wearing a natty dark grey tweed suit, a navy blue and red checkered sports shirt, and a warm grin.

The greetings over, with the frank and friendly curiosity that is his—whatever his surroundings—he began to case the place. Then turning he asked earnestly, “What can I tell you that will help you? I want to—very much.”

This was when I knew I’d better throw away all the preconceived notions about Montgomery Clift and start all over with Monty as he is. Not the mystery man, not he moody intellectual, not the shy recluse, not the eccentric with one suit and two thoroughly tired ties. They couldn’t be kin, the man and the myth.

Small wonder his friends ask, “These legends about Monty—where do they come from?” They resent any necessity of championing or defending him or explaining him. Perhaps, too, they realize the futility of it, knowing there will always be two points of view about Montgomery Clift—that of those who know him and that of the many who in all probability will never understand him.

But still those who do know him ask where the legends come from. So I asked Monty.

“Maybe I’m too transparent,” Monty says. “So transparent people can’t see me. And let’s face it, what would they be missing? But most of the trouble, I believe, goes back to what has been written about me. I’ve always been under the impression you could be an artist and do your job sincerely and be yourself. But I may be wrong. The truth about me, apparently, just doesn’t make a story.

“If I weren’t in motion pictures people wouldn’t look twice at me. I live the same sort of life the everyday person lives, and I enjoy the same things. So sometimes writers have felt impelled to add the ‘extras’ to the stories about me, to make it more interesting. If I stay home to read a book, I’m a hermit. If I like to swim in salt water, it must be a channel swim. For some time a favorite theme of stories about me was “The Man with Two Ties.’ On one occasion an interviewer and I were going out to dinner. When I opened the closet door to get a coat the writer could see I had twenty ties—and still the article came out, ‘The Man with Two Ties.’ ”

Some writers have said that Monty has a low opinion of Hollywood because he doesn’t live there. But if you ask Monty, he explains just what he does believe.

“If a contractor goes to Denver to do a job, it’s no reflection on Denver if he goes back home when the job is finished. It’s the same with me. New York is my home. I’ve lived there sixteen years and I’ve loved it. I do my job, I make a picture in Hollywood—and I go back home.”

When a writer once insisted, “But wouldn’t you like to have a swimming pool?” Monty answered, “When I feel a swimming pool is important to me, I will have one.” So the writer accused Monty of saying Hollywood is hypocritical.

“They ask you to describe the woman you want to marry,” Monty says. “How can you intelligently answer that? Marriage is a meeting of two people.”

As for not talking to the press when he’s working on the set, Monty says, “I’m not the best actor in the world. I act emotionally. It’s impossible to stay in full concentration; my mind is on a thousand things. Not only would talking to writers be distracting to me, it would be unfair to interviewers.”

His is an incisive mind, one that quickly separates the truth from the tripe. As Deborah Kerr observes, “He has a penetrating reasoning that sees right through to the core of things and seldom misses. Such intellectual purity, Monty’s. His mind is so clean and uncluttered—like a very pure flame inside him. He’s one of the purest people I know.”

He’s also one of the most intense people. He lives ardently. And all he believes is in his eyes, those amazing blue-green eyes which seem to see straight to the soul. He has strength which belies his boyishness. A lyric strength compounded of a tough mind and an equally tender heart. He’s stubborn when provoked too far. And he’s maverick, this Monty Clift, vigilant in his belief of a man’s right to be himself. But a maverick by what his heart sees.

Monty and Frank Sinatra became close friends while they were working on “From Here to Eternity,” each having recognized in the other a kindred soul sympathetic to the preservation of man’s individuality. And with the freedom of some years of acquaintance I asked Frank, “Why do you like Montgomery Clift?”

“Monty? He’s a sincere artist,” Frank answered, “intelligent, very serious about his work.”

“But,” I persisted, “why do you like him?”

“Why do you like anybody?” Frank said. “I don’t ask myself why. If you like a man, you like him.

Monty reacts to people instantly, with a warmth that reaches out eagerly. As one who knows him well puts it, “When Monty likes you, you can feel the light turn on.” And Monty says, “You meet some people and you know them immediately. Others you would never know.”

One thing sure, subterfuge in any form, with Monty, would get you nowhere. A motion-picture executive worrying how to get him to agree to participate in a project the studio felt was quite important, called Howie Horowitz, assistant to Producer George Stevens, and Monty’s good friend since he made “A Place in the Sun,” saying, “How do we handle Clift on this? How do we go about tricking him into doing it?” Horowitz advised drily, “I’ll tell you how you ‘trick’ him into it. You call him on the phone and you ask him. That’s exactly how you ‘trick’ him into it.” A few minutes later, the exec called Horowitz back saying, dazedly, “What do you know—he says he’ll do it!”

Asked whether he would consider himself a rebel, Monty says slowly, “I guess so. Certainly I believe a man in revolt is better than a person who accepts what’s handed him, or what he reads, just because it’s been accepted—until it’s been proved worthy of acceptance.” And in respect to men of conviction, Monty says, “I believe Frank Sinatra is a monument to our time. The things, I feel, people are sometimes asked to put up with in the field of entertainment—or any field—are tremendous. Frank will compromise to realize an objective, but he draws a line beyond which he won’t go.”

Will Monty compromise? “Certainly,” he says. “It’s your job to try and adjust to things within a certain scope of understanding, and as long as you keep focus as to what you’re about, it’s fine. But if you compromise until all identity is lost, compromise to the point where you’ve lost focus on what you set out to accomplish as a human being—it’s no good.”

Not that he considers himself any criterion on accomplishments. “I’m lacking in many things.” He insists he’s lazy.

This in no way reflects the opinions of those who’ve worked with him. As Manny Klein, famous trumpeter who coached him on the bugle for “Eternity” says, “I’ve been playing a trumpet and bugling for thirty-five years—but the kid wore me out! Such diligence. I’ve never seen a guy work so hard.” At 6:00 a.m. the lone figure marching around the Hollywood High School athletic field, near his hotel, was Montgomery Clift, learning to make like “soljer.” So determined was he to master every military detail, Colonel Pendleton Hogan, who served as technical adviser on the picture, would have been delighted to recruit him permanently for Uncle Sam. Monty ran fight films, and reported three weeks early to work out with Mushy Callahan for the big slugging scene. “He wanted to look like Sugar Ray Robinson when he fights,” Callahan observed.

Monty’s intense concentration results in such realism that Deborah Kerr says, “You have the strangest feeling he’s actually experiencing the scene. You could feel the knife in Monty’s side for days after his fight with Fatso in ‘Eternity.’ When he was shot, it wouldn’t have surprised me if they’d said, ‘He’s dead.’ ”

This, Director Fred Zinnemann, from his six years of association with Monty, explains with, “He’s so good an actor he gives the feeling he isn’t even acting. That he’s just being himself. Monty is technically one of the greatest actors I know. He couldn’t play a part he doesn’t believe.”

He didn’t work for two years after “A Place in the Sun,” turning down script after script because he didn’t believe any of the parts were right for him. “He needed the money, too,” a friend told me.

Then came three believable parts in one year. The priest in “I Confess,” Prewitt, and that of a young American-Italian professor in the David O. Selznick—Vittorio De Sica production, “Terminal Station,” a love story told with all the De Sica realism, the passion and despair. Filmed against the dramatic background of Rome’s Terminal Station, it’s the last hour and a half of a love affair. “It’s a very good part,” Monty says, “and I’d always wanted to make a picture with Vittorio De Sica.”

Monty has an insatiable curiosity that encourages exploration. “You see kids today who are cynics at eighteen,” he says. “They’ve had it. All of it. That’s sad . . .”

It’s easy to see why his kid-like zest and eagerness to explore would draw children to him like a Pied Piper. “He loves them and they love him,” his friend Howie Horowitz says, speaking for his three small daughters. “They think Monty’s a kindred soul and so much fun. He kills them.” As for the Fred Zinnemann’s thirteen-year-old son, Timi, he thinks of him fondly as an older adopted brother. “He adores Monty,” his parents say. When it had developed Timi would be in New York for a few hours en route from a European summer, Monty made excited plans for Timi to see the Big Town via helicopter. Monty felt certain there would be some way of engineering it. No wonder their son adored him. This would really be a boy’s idea of sightseeing. “Why, no,” Mrs. Zinnemann laughs. “Actually it’s Monty’s idea. You see—Monty’s never been up in a helicopter.”

And as for New York, the popular conception of Monty Clift as a moody recluse who fox-holes into a coldwater flat between pictures, is as mythical as the rest of it. “It’s a very nice apartment,” Monty protests laughingly.

His place in the East Sixties in New York City is a walk-up with a spacious living room with a high-beamed ceiling and a fireplace, a bedroom, a small kitchen, and a view—on a clear sunny summer day—of Gloria De Haven relaxing in her back yard. Monty’s living room is lined with books on every conceivable subject from Freud to Mickey Spillane. His fabulous record collection includes musical offerings by everybody from Bing Crosby to Beethoven—and heavy on the Bing. “I love music—all kinds,” says Monty. “But I’m getting a little old for the classics now; I like them livelier.” He drives a Buick sedan. And he has a tremendous appetite, best satisfied by thick steaks ordered “black and blue”—burnt on the outside and gently bruised within, and fortified with strong black Italian coffee.

Contrary to common belief, Monty doesn’t come from a very wealthy family. If by all written accounts he seems to have been born at the age of thirteen, when he first set foot on a stage, it’s because, with characteristic consideration, he has refused to subject his family to a spotlight they didn’t seek and which might be unwelcome to them. His father is affiliated with a New York brokerage firm, and Monty was offered all advantages—he would be the first to say—whether he took them or no. His mother, Monty describes as “a very sweet person, a woman of tremendous energy, and with a comprehension of those things which mean good taste in living.” His brother, Bill, is in television in New York. His sister, Mrs. Robert McGinnis, is married to a Dallas attorney, and raising four little fans for Monty. The fact that he’s closest to her, he explains with, “We seem to see more alike, feel more alike—maybe because we’re twins.”

Ask what inspired him to become an actor and Montys’ stuck. “I don’t know,” he answers slowly, “and I’ve asked myself many times—why I felt impelled to be an actor.” Particularly on those occasions when he’s unhappy about some scene he’s done—or feels he failed to do well.

But for all the self-torture understandable in so sensitive an actor as Montgomery Clift, he has never at any time considered any other vocation. In his lifetime he’s held only one other job, laying pipe on a ranch in California, when he was forced to leave the stage following the run of “The Skin of Our Teeth,” ten years ago, to recover his health.

“I was very ill, down to 144 pounds,” he says. “I’d contracted a mysterious amoeba in Mexico—at least it seemed a mystery to doctors around New York. Today they would know how to treat it instantly, there are so many wonderful drugs. But they couldn’t seem to diagnose it then.”

Reasoning that with fruit boats plying back and forth from the tropics putting in at New Orleans, doctors there might have more knowledge of amoebae, Monty went there. And they had. “In New Orleans a wonderful doctor, a Dr. Browne, knew immediately. He saved my life. After getting out of the hospital, I’d planned to work as a longshoreman until I got stronger, but the climate was too hot and humid there for me. I’d met some people who had a ranch in the Napa Valley in California, so I just wrote them—‘I’m coming to work for you.’ I laid pipe on their ranch until I got my health back again.”

Monty rejects any thought of employment other than acting. “I can’t think of anything in which I’d be very useful.”

Although Monty may say, “I don’t consider myself a religious man”—his whole philosophy of living, his whole reason for being, is in a sense Scriptural . . . “You shall know the truth—and the truth shall set you free.” To Monty Clift they go hand in spirit—truth and freedom. How much is in his eyes when he says, “Freedom is the one thing I treasure. The one thing I hold onto. The freedom to reach toward what you believe . . .”

“I’ll call you before I leave town,” he said, after talking to me.

Officially, he was already gone. Columnists were casting his next picture when he “returns to Hollywood.” But Monty—well—now I knew too . . . you can set your watch by his word.

And so one night the phone rang. He was in the middle of packing, if we would pardon the expression. He was leaving the next A.M.—he hoped. How would I recommend getting a pair of GI shoes into two inches of bag space. From where he was sitting, on top of the bag—it seemed a mathematical impossibility. They were Prewitt’s shoes. They’d gone through “Eternity” together—and some way . . . they were going to leave Hollywood together too.

The future? It was wide open . . . “I don’t know what I’m going to do next,” he said. More importantly, he didn’t know for whom or how or where. “To direct, some day, that’s my distant dream. To direct and act, that would be ideal.

“Perhaps it will be in independent pictures,” he said, after a pause. “I don’t know. But I do know I’ve got to have some say about me, about what happens to me. I must be free to go about my work in what seems to me to be the right way. What that way will be, I’m not sure now. But in the meantime, what am I going to do about these shoes?”

There seems to be small cause for concern on either score. A man who loves a thing as much as Monty Clift loves acting will find a way. And a guy who’s come so close to finding that way would hardly be stopped by a pair of shoes.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1953