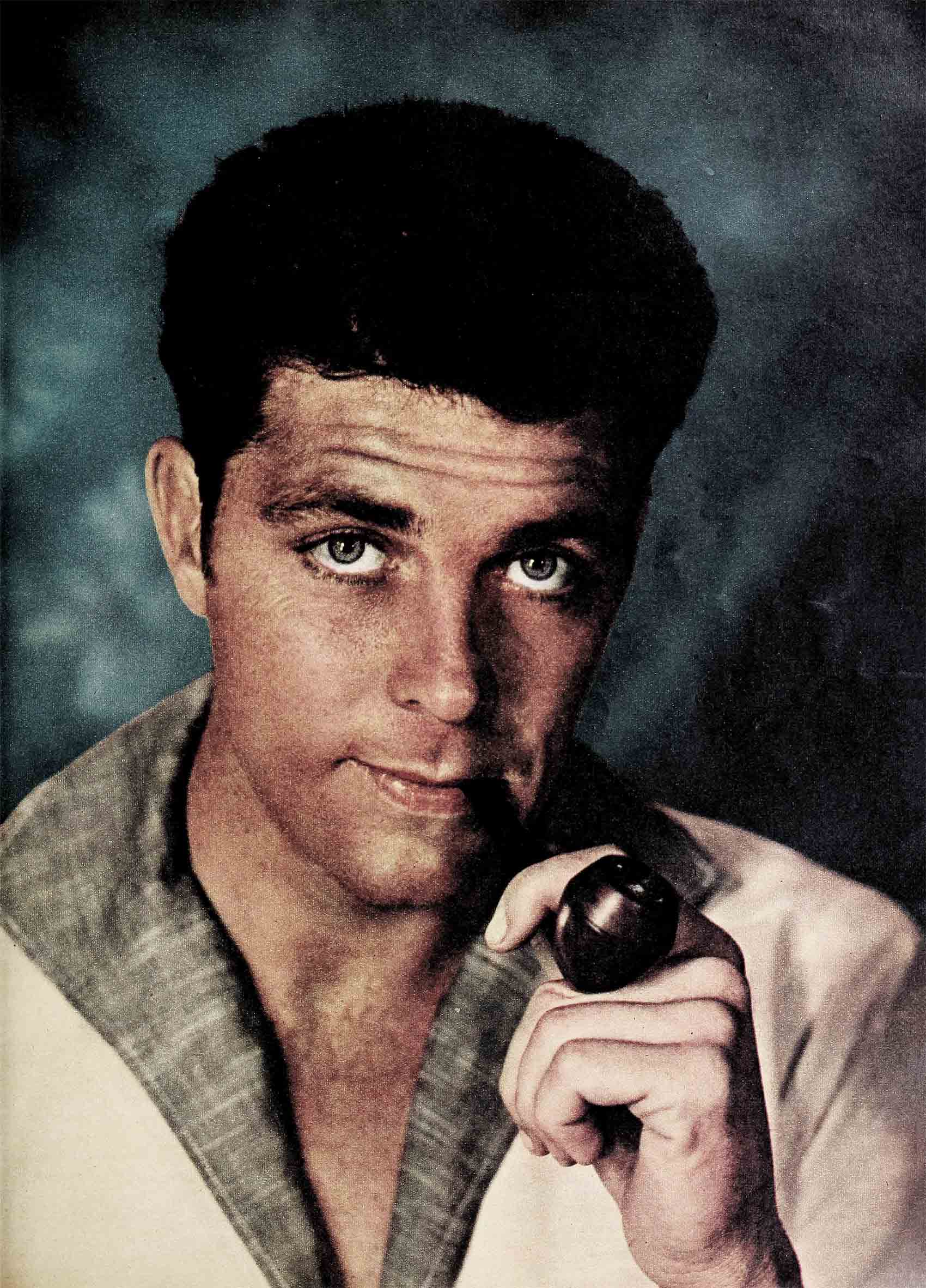

“ Want A Divorce . . .”—Dale and Jacqueline Robertson

In the still of night a small child’s voice cries out. Suddenly awake and startled, “Mama!” she calls. “Dadda?” Her father gathers her close and soothes her to sleep again. But on through the darkness, a cigarette glows and the night is crowded with all that might have been. Thoughts march across the memory and a man, Dale Robertson, weighs them against a child’s cry.

Dale’s daughter, Rochelle, will never lack for love. When her mother isn’t with her, her father will be there. She will always have them both.

But what happened to those two whose whirlwind romance swept Hollywood off its heady feet? Two strangers who fell in love at first sight across a crowded room, who were engaged five days later and married five short weeks after they met. The two who pledged their troth before a candlelit window, high on a hill, with all Hollywood a magic glittering carpet at their feet, who toasted so confidently the years ahead that would be . . . The years that now will not be.

When does marriage end and divorce really begin? When do dreams and hopes dissolve—into mental cruelty! They’d been to Oklahoma, but things seemed about the norm. They’d just finished carpeting the house. Jacqueline had picked out the carpeting—a warm beige design. There’s something about all-over carpeting that seems stable.

They were sitting in the living room looking at television. Dale was going into the kitchen for a glass of milk when Jacqueline stopped him, saying suddenly, “Dale, I want to talk to you.” He sat down.

“All right. What is it?” he said.

Her voice was firm. “I want a divorce.”

Four words. Finally spoken for the last time. The pause seemed longer than it was.

“All right,” Dale said with finality, and went to pack. An anti climax for a whirlwind romance and marriage. But divorce had already become a familiar word, too familiar, before this final disenchanted evening when Jacqueline threw in the hand without waiting for the final cards.

The charge? Mental cruelty. Two words which can’t cover three years any two people in love share. Certainly not for a man like Dale, to whom marriage and home and family are meaningful words.

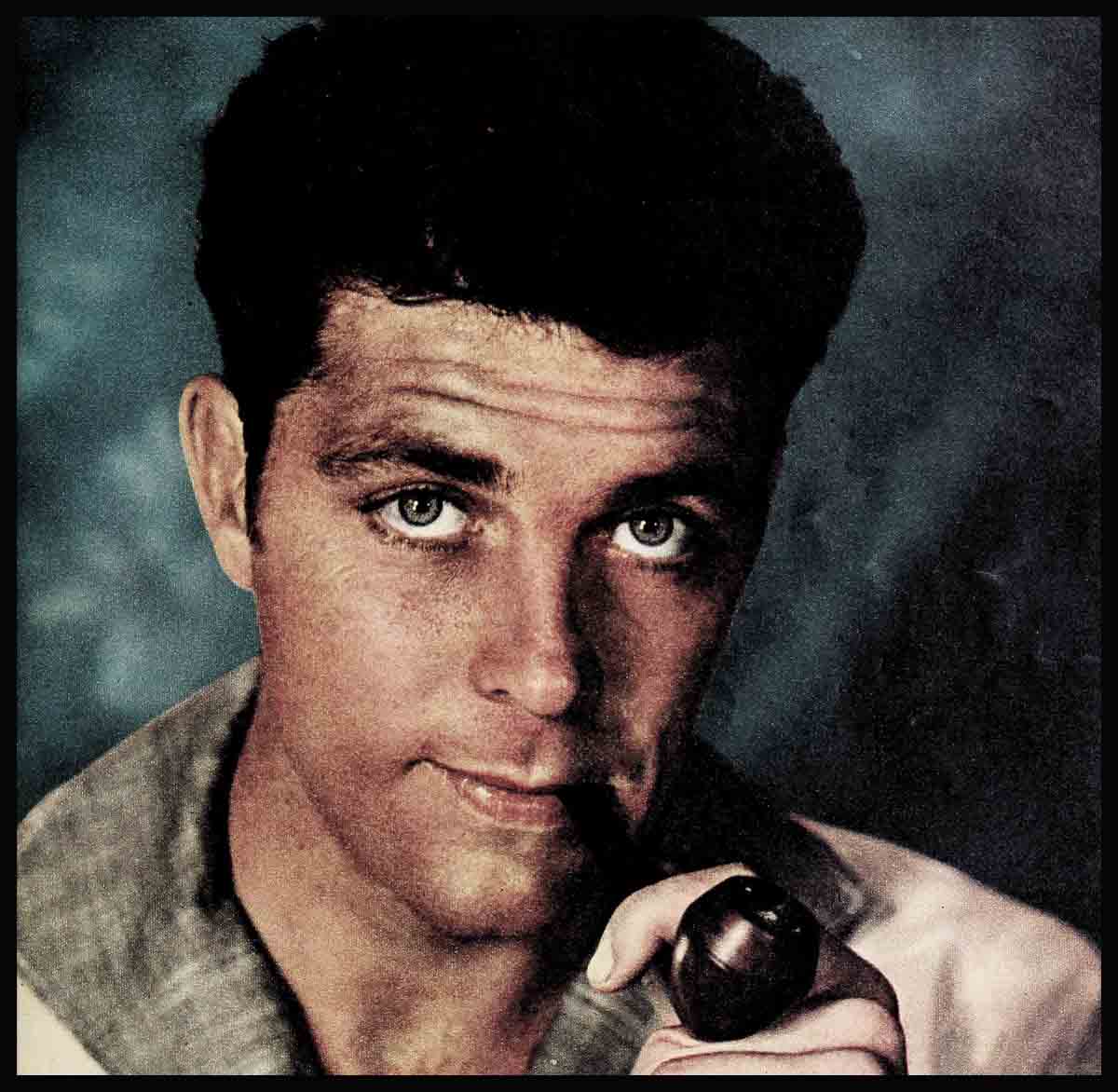

More restless, thinner by seventeen pounds, as Dale says slowly now, breaking a too-long silence as the year ends, “Divorce isn’t a word to be taken lightly. Nor is marriage. Anybody can get a divorce. That’s the easiest thing in the world to do. The tough thing is to keep sticking and work it out. Anybody can fall in love overnight and get married, too. But it takes time to make it work. I’d told Jacqueline the next time she mentioned divorce she’d better mean it. That I didn’t want it thrown in my face all the time. I said that because I wanted her to think it over very carefully. Not just every little thing that came up to start talking about a divorce. I wanted her to really think about it, weigh it and if she said it again, say it because she really meant it. And I think she had thought it over. Whether or not she ever quite convinced herself marriage is a happy way of life, I don’t know. I prefer to think she did. We’d just redecorated our house the week before. I assure you there was no thought in my own mind of getting a divorce. And there was no third party—not as far as I was concerned. . . .

“I’m not blaming Jacqueline,” Dale goes on quietly. “She has her reasons. And it takes two to get married and two to get a divorce. If a man is all a woman wants him to be, she will work very hard to be all he wants her to be.

“There are things I can’t talk about,” he adds. “Things that could be remedied, but it would take a great deal of effort on both parts. And it would take a long time. I’ve known marriages to last forty years when people have fallen in love overnight, but they’ve really worked at it. And they’ve given it time to grow.”

But time ran out too soon for Dale and Jacqueline Robertson, leaving them linked by some happy and not-so-happy memories. And linked always by a rosy-cheeked little two-year-old queen of an animal-kingdom nursery. A nursery her father painted three times because he wanted an exact shade of blue, and where he sang her to sleep at night, accompanied by a big friendly blue elephant with pink ears that tinkles Brahms’ “Lullaby.”

Only those very close to him would know how much his marriage, his home and that nursery could mean to Dale and how hard, in his own way, he tried to preserve them. Few know how both sensitive and earthy he is. An often antagonistic press is uninformed about Dale and he’s shown little inclination to enlighten it—particularly when it pries too close to his heart. He’s guided, concerning his marriage, partly by a Confederate chivalry, partly by a stubborn conviction that it’s nobody’s Yankee business anyway.

For nine months following their separation, Dale kept floating around, hanging his hat at the home of friends where he could feel a warm and close family tie. He would stay in Hollywood with his stand-in, Kit Carson and Carson’s family, or out in Woodland Hills in the valley with old friends he’d met through horse shows. “I’m going to have to get some place of my own,” Dale kept saying then. “I dread to, but I can’t just keep living off everyone else.”

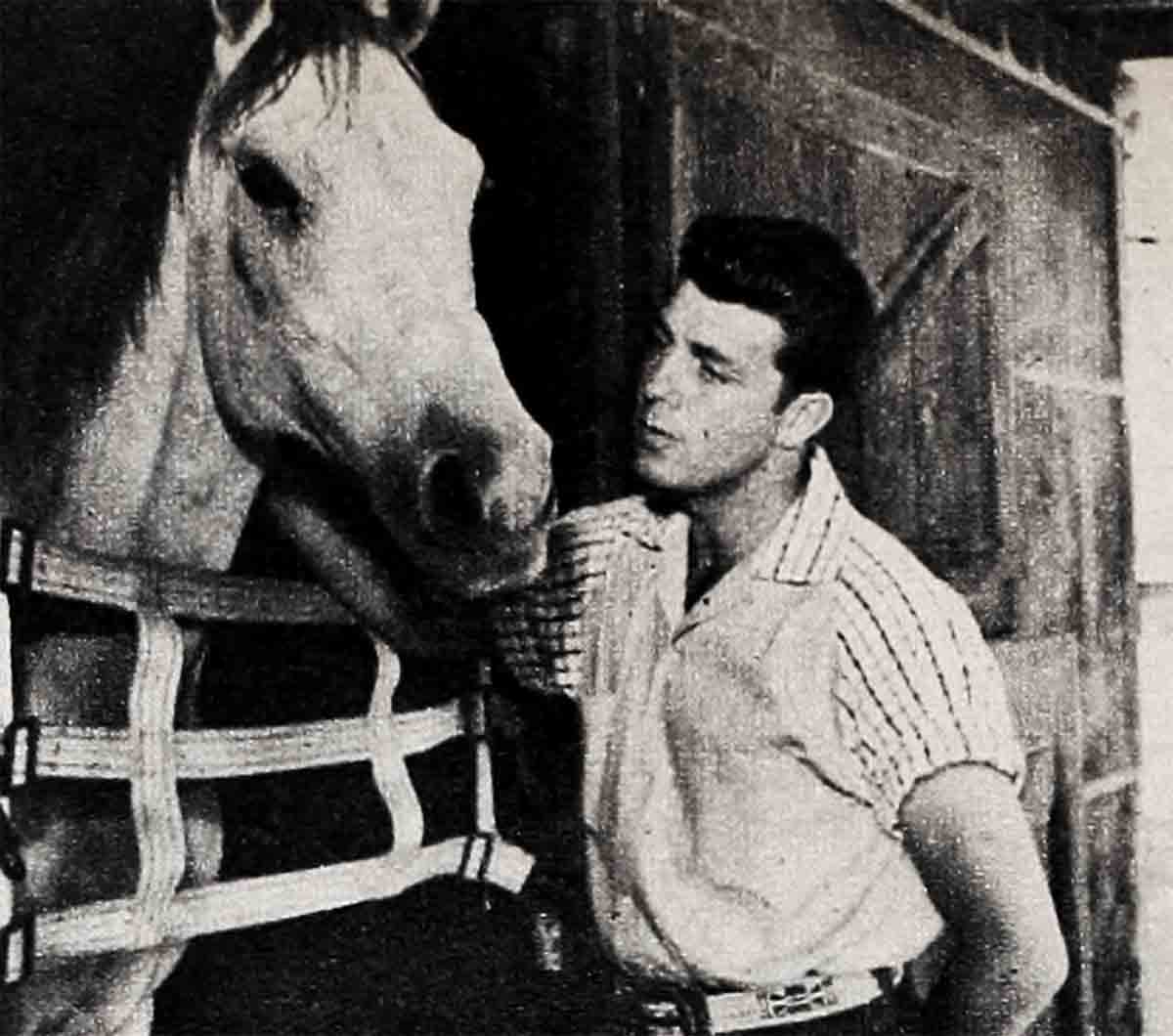

Now Dale and Chief, his German Shepherd dog, are batching in a “small sort of modern-type” furnished house in Toluca Lake, the section where Dale lived for a while before going into pictures. Chief, whose heart is beyond any court’s custody, always keeps one devoted brown eye affixed watchfully on Dale when he talks, seconding every word. “Now that I have a place, whenever Jacqueline’s out of town at horse shows, I’ll keep Rochelle with me. You should see her now. Let me tell you, she’s a dandy!”

“She’s a dandy.” Remembered words from almost four years before. “She’s a dandy!” he’d said of lovely nineteen-year-old Jacqueline Wilson. They rode horseback. He had a ball team in the valley, and he took Jacqueline to some of the games. He took her out to his comfortable three-bedroom GI house in the small town of Reseda to play pitch with his Aunt Iona and Uncle Omer, who then lived with him. “They’re crazy about her—and they’ve been married forty-six years!” he beamed to friends. And he told her of his ambition to write. Colorfully, he outlined the plots and characters in stories he’d written. The girl in each of them he was sure was Jacqueline Wilson. And to her, Dale embodied the hero in every story he told.

Theirs was a wedding for any bride to remember and a gay reception set to moonlight shining through the stately Eucalyptus and a strolling accordionist’s “On Top of Old Smokey” and “Be My Love.” A girl, radiantly beautiful, revealed she’d found out all the basic, important things about Dale from his stories. “In every story I realized he was the hero. He was describing himself. I knew him through them.”

As they raced through a shower of confetti down the hill into the glittering world founded on boy-meets-girl, those there were sentimentally reminded that life can write better love stories than any scribe can imagine or the screen can tell. But life writes it’s own realistic and unhappy endings, too.

One clue to basic differences in their troubled future occurred during the first hectic happy days before they were married. Dale wanted a simple ceremony with a minimum of fuss. Jacqueline wanted a home wedding. Her mother, an actress of the silent-picture days and socially minded, was making out the wedding invitations and asked Dale if there weren’t some people at the studio he wanted to invite. She listed various important studio executives, including Darryl Zanuck, whom Dale had still never met. “I thought you would want them to come—the people you work with,” she offered.

“Do you know these people?” he asked then. “Are they friends of yours? If they are, it’s all right. But don’t invite them for me. If you’re going to ask my friends from the studio, ask them all, including the ones I work with, instead of just the people I work for but hardly know.”

When the stardust cleared, Jacqueline naturally didn’t embody all the heroines in Dale’s stories and Dale was no hero, but a man with all the sometimes maddening male qualities. He was as strong-minded as his heritage. And Jacqueline, for all her seeming poise and sophistication, was as young as her nineteen years and unequipped by background or experience to weather so soon the responsibilities of marriage even to one with Dale’s stable, however strong-minded, values. While Dale’s mother owns the Robertson Convalescent Hospital for older people in Oklahoma City—which she built from scratch—and they had always been reasonably comfortable, Dale had been educated for the finer arts in living but not the froth.

It was early evident theirs were different definitions for love and marriage and happiness and for what many of the important things in life are. Too different to be dissolved by moonlight shining through Eucalyptus or a week’s heart-to-heart talks. With Dale’s deeply rooted Cimarron background and Jacqueline’s younger hot house experience, the little things that were to be adjusted after marriage began to close in, grew larger all the time. When it came to building a marriage, their values seemed as unrelated as building on rock and on sand, values that would take time to bridge.

Unfortunately there was no time for a honeymoon or any adjustment period after they first married—unfortunately for a very young bride. They were married on Saturday, spent their wedding night in Santa Barbara and Dale was due back on the set at 20th Century-Fox on Monday. They planned to honeymoon later at romantic Banff and Lake Louise. But Dale was thrust into one picture after another. “I’d like to be married all over again,” Jacqueline once said. “It happened so fast. Sometimes I can hardly realize it.” And then, before she could grasp many of the responsibilities of being a wife, she was a mother. When Dale finally got two weeks off, they went to Oklahoma City to Dale’s mother’s where the Robertson clan gather from far and wide for Christmas every year. This was Jackie’s first introduction to Dale’s home town, and to many of his people. She was ill from the first weeks of pregnancy. The whole trip was a pretty miserable experience. It’s doubtful, too, whether Jacqueline ever felt at home in Oklahoma. And while Dale always encouraged her to spend time with her family, he seldom went along. He’s no student of small talk he doesn’t feel, and his is an inborn horror of, as he used to put it, “Just sitting there—feeling like a hypocrite.”

Admittedly “old-fashioned” when it comes to marriage or his home or his family, Dale was determined to build his own marriage and happiness on values that would last. With patience, he hoped to persuade Jacqueline to accept his values. In her way, she gave it a good try. And Dale loved her more than perhaps even Jacqueline realized—in his way—which was not her way.

Mental cruelty.

Fragments of arguments, phrases, sentences, fears—and a few tears—walk like ghosts across a memory. Familiar ghosts to many marrieds who’ve survived them.

Jacqueline’s half-laughing, “He’ll buy me a set of golf clubs. But he doesn’t understand women’s tastes. He thinks clothes are sort of frivolous.”

And Dale’s, “We can’t go off the deep end and make bills we can’t pay. I’ll get a mink coat when we can pay for one. I’ll get another car when we can pay for it. I’ll get a new home when we can pay for it. We’ll have all these things—when we can pay for them, but not till then.”

Jacqueline’s rueful admission, “I have an irky habit of always asking him when he will be home. I seem to ask him every time he leaves. I’m not trying to pin him down or anything. I realize it’s ridiculous, because he can’t know exactly what time he’ll be through shooting at the studio and get home, but still I ask.”

Jacqueline wanting to do part-time picture work, even working as an extra now and then. Dale’s logical reply (for he has strong thoughts on such subjects), “You wouldn’t want to take a pay check from somebody else who really needs it, would you?” And Jacqueline agreeing she would not.

Dale’s frank admission, too, “I’m old-fashioned and I know it. I was brought up to believe a husband is the head of the house, the bread-winner, and it should be that way.”

Jacqueline’s, “He says he loves me, but he never calls me and asks me to come out to the studio. He never takes me on location or calls and says, ‘I miss you.’ ”

And Dale’s reflective, “I’ll never forget, before we were married, somebody in her family said to Jacqueline, ‘This will be wonderful. You’ll be going to premieres and parties. You’ll be going on personal appearances with Dale, on location trips, to the studio. You’ll really have a gay life,’ And Jacqueline said then—and I loved her for saying it—‘No, I think a man has his work to do. A wife shouldn’t expect to always be tagging along.’ I thought then, ‘This is just wonderful. I’ll take her with me when I can, and when I can’t, she’ll understand, too. This will work out just fine.’ Well, that theory was blown to blazes the first three weeks.”

How understandably upset a sensitive bride would be: When Jacqueline called the set one day to tell Dale their happy suspicions were confirmed—they were going to have a baby—on the other end of the telephone, he replied simply, “Oh, I’ve got to run,” and hung up. He explained later, at that second the assistant director called him for a scene and he had to hang up. Dale’s joy in fatherhood was expressed in his own way. Working on the nursery in the evenings. Bringing Jacqueline back a glamorous lamé jacket and a very smart suit. The picture of a masculine guy like Dale shopping for maternity clothes would be more proof than words. But there were words, too. “You know, I never thought I would have a child. I’ve wanted one. I used to think about it a lot. It still seems just too good to be true.”

Dale’s preoccupied moods were sometimes disturbing to Jackie, and Dale has admitted, “They can be hard to understand. It’s easier to see somebody else’s shortcomings than your own. But I have my share. Of that I’m dead sure. I’m not too easy to live with. And I do get quiet and that isn’t always easy to understand.”

The strong and silent can be difficult for those less emotionally secure to understand. During one of Dale’s silent moods Jacqueline once burst into tears, saying, “You don’t love me.” On another occasion, she once said, “Dale is so strong. Nothing bothers him.”

But Jacqueline would have been surprised to know, too, how many times her husband needed his wife’s strength. As he says now, “There are times when a woman is a little girl to be protected and loved. And that’s as it should be. But there are other times when both a man and woman must be strong and face their problems together.”

And there were times when it must have been pretty difficult for a man with Dale’s usual inner strength, a man as self-sustaining, to understand the need for constant reassurance, the fears that can beset a wife—fears, however unfounded, that can undermine a wife’s trust.

Unfounded reckless items in Hollywood gossip columns and malicious unsigned stories in magazines used to worry Jacqueline. “But why would they say that if it isn’t based on something?” she would say. Despite Dale’s reassurance, “If the day ever comes when I come home at night and I can’t look you in the eye, then there’s something to worry about. But these things . . .” he’d say, shaking his head. Nor could Dale understand why she didn’t have more faith in him. One gossip item linking him with a famous motion-picture star was so ridiculous a writer-friend called a publicity man at the studio where Dale was going on loan-out and asked him to set the columnist straight before damage could be done. “What’s wrong with being linked with a gorgeous doll like that?” he said, surprised. “Three things: Dale’s wife and baby—and he’s never even met the girl!”

Dale resented such items because they were so upsetting to Jacqueline. His own tense-jawed attitude with such columnists did little to help, and on occasion it would be Jackie who would defend him with them, resent it, wondering, “Why don’t they say something bad about me?”

Because it was obvious Jacqueline seemed to need so much reassurance and wasn’t too happy when he was away from her, Dale tried to keep his personal appearances to a minimum. An outdoorman, he limited any sports that would take him away from her, like hunting, fishing or playing golf. The one day he played golf, Sundays, he would get up at 5 A.M. to be home by the time Jacqueline awakened, to be with her the rest of the day.

Which would seem hard to reconcile with some barbed views Jacqueline’s given out since their separation, giving Dale’s career as the cause for their trouble. Stating he cared more for his career than for his family and didn’t have time to work at their marriage. Also that “movie wives have to take a back seat in marriage anyway.”

If movie wives take a back seat, it’s Dale’s view—and it’s always been his view—“They get into it themselves. They have a career, too, in trying to make a home. I don’t mean just keeping it dusted and Hoovered and the dishes washed. I know that’s very dull work. I never really cared about that. There’s far more to making a home than that.”

And certainly Dale’s career should never have separated them. Any strong-minded views he’s maintained which have sometimes been attributed to a star-swollen head, he would have maintained roughnecking in his native Oklahoma oil fields. To Dale, making movies is a business. He used to worry about his family’s future, and, believing any actor should have a side business, too, he invested in Everlast Laboratories. When he wasn’t before the camera he would be out selling their product, or in overalls at the new plant pounding nails, moving furniture and working as just another hand. But he still managed to spend an average amount of time with his family.

“Funny, when a man works as a butcher or carpenter he has a job. But when he’s an actor, he has a career.” Dale says now, shaking his head. “Acting is just a means of support. An actor sells entertainment for other people. Like a carpenter, he needs the money to support his family. I did think more of success after I married than I ever had before. Because of Jacqueline and Rochelle. I wanted to be able to put something aside, so if something should happen to me, they would have enough to go on. But in any marriage, if two people can be together as much as we were together, they spend ninty-seven per cent of their evenings together and ninty-nine per cent of their Sund ays together, there’s no reason why their marriage shouldn’t be right. And no couple, where the man—can be together much more than that.”

During those three years when they hoped to achieve understanding, he tried to make Jacqueline understand that adult love is guided by more than physical presence. “You can love someone just as much when you’re away from her,” he would say. And doubtless there were times when he left things—things a wife likes to hear—unsaid. In his marriage, as in his work, as in life, Dale was motivated by the words of Edgar A. Guest whom he loves and lives by:

I’d rather see a sermon than hear one any day—

I’d rather one would walk with me—than merely tell the way—

By deeds rather than words. His reaction to this, then as now, was, “We have to show that love and respect are there. To say, ‘I love you,’ isn’t too hard. But to show it is something else. Maybe I didn’t show it too much with words, but words are cheaper than water. A wise man can spout off many words, but so can a fool. You can take a breath and say thirty words. But if you don’t back up those words, then it won’t work out in the end anyway. We all want to be loved, but we can’t just sit back and say, ‘Love me.’ We all have to earn that love and keep earning it. I tried to show Jacqueline I loved her. But my way of showing love wasn’t her way.”

Theirs was a different definition for happiness, too. For all the “preview” Dale gave her before marriage of the simple life they would lead, this wasn’t Jacqueline’s idea of excitement and gaiety. Dale took the long view of building happiness together and anchoring it. How far apart they were on this score he discovered one night when Jacqueline said, “I’m just: not happy any more.” Dale asked what it would take to make her happy. She said she didn’t know. “Well, what did you do before we were married that made you happy?” he asked. “I went to parties and had fun.” Dale said then, “You don’t know whether you were happy or not. That wasn’t real happiness, that was synthetic.”

Reminded of this now, Dale says, “True, we didn’t go out much. We didn’t go to many parties, and she couldn’t understand it. But parties are no source of happiness. They can get very boring and pointless. I tried to build happiness for us with the things that keep you happy for a lifetime—not just a short while: by learning to know people and like people, by building love for our home and for good friends. Real friends who would still be our friends after the tinsel wears off, after the movies and this temporary success. And everything I said or did wasn’t because I didn’t love Jacqueline but because I did love her, because of our future, because I believed I knew what would make her happy, too, in the future. I tried to build real lasting happiness.

“Who was it that said, ‘Happiness is like time and space. We make and measure it ourselves’? It isn’t easy to find at best, and I guess that’s about the size of it. But if you could grab it out of the air, it wouldn’t mean anything or be worth working for. I think making a home could be a source of happiness. And I wouldn’t think any woman with children should find too much time on her hands. She has the greatest gift and the greatest career God was able to give her.”

Divorce has never been Dale’s idea. Nor his solution. Friends hoped their reconciliation after some brief trouble two years ago would achieve a better understanding. Jacqueline was hurt when Dale, under great pressure, wanted to get off somewhere and think by himself for a few days, thinking this would be better for Jacqueline, too. She felt deserted and miserable, “Dale shouldn’t be married. He wants to come and go, keep his freedom.” But it was Jacqueline who constantly mentioned securing that freedom. Not Dale. He was the one who got upset if she mentioned divorce. Later they seemed very happy. As she put it, “We’ve both changed for the better. We’re not as stubborn as we were before. I’m not as sensitive as I was. And Dale—well, he lets his emotions show more.”

But the ranch-type home they talked of building in the Royal Oaks section of the valley, where the rolling hills roll up to meet the sky, will never be built. Not for them. . . .

The girl who fell in love with the handsome movie star “hero” of his stories and the guy who thought his love embodied every heroine he’d ever imagined know now that in the daily drama of two human beings living as one, heroes and heroines belong strictly where they are—in the storybooks.

Dale readily admits, “I’m quite sure I expected too much of Jacqueline. But I also think she expected too much of any one man. She frequently pointed out to me-the good points of many men. But if I am expected to have the good points of seven or eight men then I’m bound to have some of their bad qualities, too.

“We went to a marriage counselor once. You fill out papers, and they make a graph from questions and answers. Our graphs went in exactly opposite directions. How much that means, I don’t know. But I do know when it comes to building a life together, we didn’t see things exactly eye to eye.”

As for any chance of ever getting back together, Dale says, “I don’t see how. I don’t see how we could talk ourselves back together now. I’m no angel—I’m from Missouri. And I have to be shown. And Jacqueline’s from the other side—same state. As I said, there are things that could be remedied. I still feel with more time and effort our marriage might have worked. But I think Jacqueline decided some time ago she didn’t want to try any more. Now I just want to get it all over with, and see the baby’s needs taken care of,” Dale says slowly.

Her father has given a great deal of thought—and heart—to how their divorce will affect Rochelle. “I’ve made provisions for Rochelle’s education that will take her right through college. I did that right after we separated in the event anything should happen to me. Jacqueline wants her to go to private schools. I’m not for that, but that will be up to Rochelle. I don’t like the idea of shipping kids off to private schools away from their family, maybe against their will. When she reaches that age—if she wants to go—I’m not going to object. I’ve arranged for a settlement to be given her in a lump sum when she finishes college. I did that for her own protection. If anything happens to me, or to Jacqueline, I don’t know who would raise her and I, want to be sure she’s taken care of.

“Jacqueline’s afraid Rochelle’s turning into a ‘mama’s girl,” Dale goes on thoughtfully. “But I don’t think so. Her mother will be with her most of the time, and I want the baby to love her and miss her—feel very close to her. Rochelle would never be too possessive anyway. She has too much independence for that. And it’s important to give her all the love we have between us. She isn’t going to have a mother and a daddy both, so I don’t think there’s any danger spoiling her with too much love.

“We’ll always discuss together what’s right for her and hope and pray we’re both right. We’ll have to work hard to teach her the right things—things that will make her happy and not spoil her. I’d like for her to grow up knowing how to make a home, so if she falls in love with somebody who can’t give her what her mother and father gave her, she will be prepared and it will spare her a great deal of trouble later on. I want her to know the real values in life—love, friendship, a home. The important thing is to spend time with her—I don’t think you can spend too much time with a child. And to give her all our love.”

A mother’s love—Dale knows about that. He remembers too well another kid. A boy six years old when his father and mother separated. “I missed my father like any kid. But my mother worked doubly hard to see we didn’t miss anything—and she succeeded. Rochelle will never need to know what it is to miss anything either. And as long as she’s a growing girl, I’ll guarantee I’ll never be far away from her.”

The future? For months Dale has been dating Mary Murphy, talented and lovely little Paramount starlet. With freedom a matter of days away, Hollywood has been speculating about them. “Mary would be a Godsend for any man,” Dale says firmly. “She has so much understanding. I haven’t gone out with anyone else because I haven’t wanted to. But I’m not thinking of marriage at the moment. I have too many problems to think about. I’m not saying it can’t happen, because it could. But I’m not foreseeing anything right now.”

Dale and Mary Murphy certainly know each other better than Dale and Jacqueline did when they were married. They’ve co-starred and worked together in “Sitting Bull.” They’ve gone on personal appearances together. There could be one problem, a source of possible disharmony. Mary, 22 years old, very pretty and very talented, is under contract to Paramount. As Dale goes before the cameras, starring in “Top of the World,” Mary has just been given the biggest break in a very promising career, the important young dramatic lead in “The Desperate Hours,” with Fredric March and Humphrey Bogart—which is indicative of what her studio plans for her.

Dale has never believed too much in career wives. “I can’t remember when two careers have been successful in one family—when they’re both in pictures,” he says. “I don’t say they can’t be. I’m not saying whether or not it can work out. I don’t know. And I don’t intend to look into the future. That’s for the prophets.”

But whatever the prophets decree for the future, the past three years leave much to be remembered, much that is good, and much that has been learned. “I’d hate to think I spent three years and didn’t learn anything,” Dale says slowly now. “The things you learn stick in your subconscious. You don’t talk too much about them. But you know where they are and they’re the jury.”

Then, as though thinking aloud of those two who descended from the hilltop into the bright tomorrow—facing life together so confidently . . .

“Our marriage lasted longer than some, not so long as others. But in those three years we were married we knew more happiness than many who’ve been married many more years. There were times when we had happiness you couldn’t put into any storybook.”

And from their union there’s a daughter Dale hoped for but never expected to have. A little glamour girl who holds all of her father’s heart in her own chubby little hand. And in the darkness of the night—many nights—Dale Robertson dreams his dreams for her.

THE END

—BY MAXINE ARNOLD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1955

No Comments