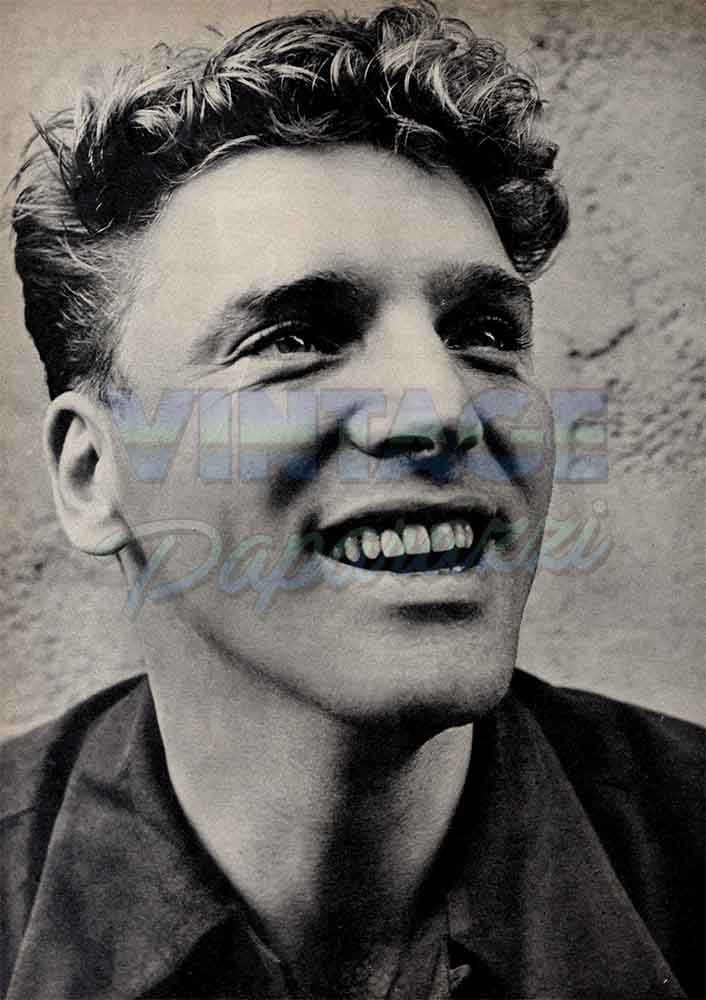

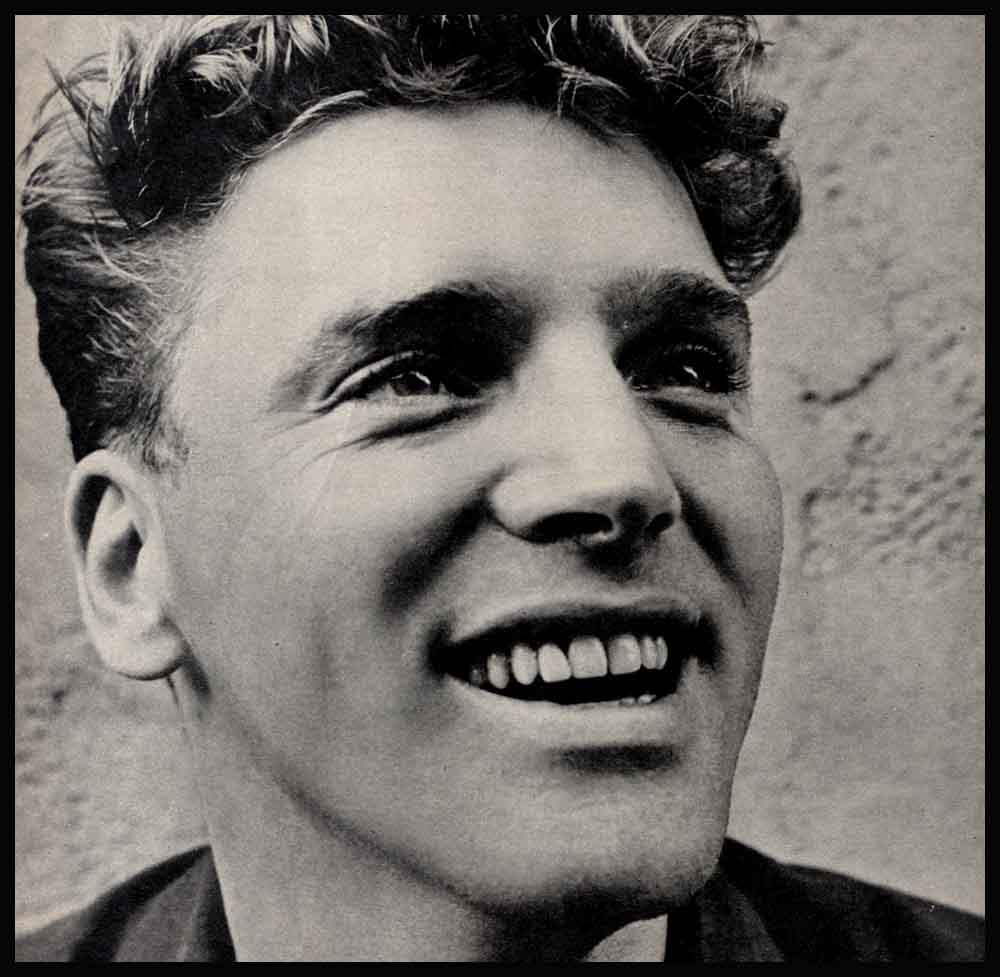

Burt’s Father Jim: “I’ll Bet On Burt”

I’ve heard Burt tell interviewers, “I was a very unpleasant little boy.” And some people around Hollywood say (not to my face!) that Burt as a man is a bristly sort of character, hard to get along with.

As Burt’s dad, I suppose I’m prejudiced, but I have plenty of facts at hand to give you a better idea of what my son’s really like. There’s a lot about the man Burt is now that keeps reminding me of a towheaded little boy with a Buster Brown haircut—yep, bangs! (It was his mother’s idea, and Burt put up with it for three or four years.) There’s a lot about Burt today that reminds me of a lanky kid with hair that seemed to have been combed with an eggbeater. (Burt threw away his comb when his mother died—just used his fingers after that.)

Was Burt a bad boy? I don’t think so. Sure, he did his share of smashing windows and being chased by cops, but that was par for the course on our block—East 106th Street between Second and Third Avenues in New York City. Maybe I shouldn’t be contradicting my son. You ever take him on in an argument? Well, don’t. One Sunday when he was a youngster, his brother Jim got to arguing with him over a baseball game. Jim said the ball was out. Burt said it wasn’t, and emphasized the point by conking Jim on the noggin with the bat. That taught Jim never to argue with his brother again.

Burt’s never outgrown his love of arguing—in the family circle and among friends, that is. When he first came to Hollywood, I hear, he used to sound off on his purely personal opinions. Probably that didn’t make him too popular in some quarters. But since then, he has learned to guard his tongue. Not that he’s afraid of free speech—he just realizes that any strongly pronounced opinion on any subject is bound to hurt some people in a large group, leading to useless wrangling or outright quarrels. Now he’s careful to know the company he’s in before he starts spouting.

He’s changed in another way since he became a star. On his first trip out of Hollywood with Mark Hellinger, the producer who discovered him, Burt arrived in San Francisco without so much as a tooth brush, let alone a change of suits. These days, he’s as conscientious about being well-dressed in public as he is about taking a fair, friendly attitude toward autograph-hunters. It s all part of what he calls “the responsibilities of stardom,” but it took him a while to begin feeling these responsibilities—maybe, I figure, because he was the baby of the family. We did have a daughter younger than Burt, but she died when she was two, so it was just Burt that Willie and Jim and Jane looked out for, fighting his fights. He had no reason then to develop the sense of responsibility he has now.

I didn’t have much time to devote to the children, with my post-office job in the daytime, and in the evening, repair work on a couple of small houses I owned and rented. I was a Sunday father—“a fun father,” Burt puts it. It was my pleasure to take the kids over to Central Park on Sunday afternoons to play baseball, eat popcorn, visit the zoo and drink soda pop. My wife really brought up our family, and a wonderful job she did.

Burt never argued with his mother. He did try it once, and he couldn’t sit down for a week. Mostly, he’d charm his way out of getting a spanking. His big blue eyes normally had a devilish look, but boy!—how he could turn on the innocence when it served his purpose. He’d see his mother coming after him with fire in her eye and a switch in her hand, and he’d start singing “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” in his good Irish tenor. It usually worked. Or he’d throw his arms around his mother’s neck, smile that beautiful smile of his and say, with more schmaltz than you’d hear in a Viennese waltz, “Mother dear, you don’t love me any more.” Mrs. Lancaster, I regret to say, would melt, while Willie and Jim, no charm boys, looked on in utter disgust.

Burt still uses that ingratiating smile when he gets backed into a corner. I believe that boy could smile his way out of anything. But in some way his mother managed to keep him disciplined. My wife had a phobia about dishonesty. She was determined that our children grow up to be decent, law-abiding citizens. I recall one day when Burt was eight or nine. He came home from a grocery-store errand with sixteen cents when he should have had only eleven. First he got a cuffing for cheating the clerk; then he was sent straight back to the store to return the extra nickel.

An incident when Burt was in high school made me proud to see how that lesson had stuck with him. Coming out of the Corn Exchange Bank in our neighborhood, he saw a twenty-dollar bill on the sidewalk. His first impulse was to pick it up and run. But he didn’t. He covered it with his foot and leaned against a fireplug to wait. “If nobody comes along to claim it in twenty minutes,” he told himself, “it’s mine.” At the end of nine-teen minutes a little old lady scampered up and asked plaintively whether he’d seen a twenty-dollar bill. Burt lifted his foot and gave her the money. Of course, he kind of ruined the story when he told it to me by adding, “I cursed myself all the way home for being such a dope.”

Even as a youngster, Burt had a shrewd sense of money. Maybe that’s why he’s produced his own pictures successfully, while so many other actors have gone broke that way. He wasn’t much good at arithmetic problems in school, but when it came to genuine nickels and dimes he was real smart. One summer, he decided he wasn’t making enough money on his paper route, so he went into the shoe-shine business. “I set up my stand outside Macy’s on the Thirty-fifth Street side, Dad,” he told me. “It’s the most profitable spot in town. That’s where the shoe salesmen go in and come out. They have to have a shine twice a day, and I catch ’em coming and going!”

Burt’s generally very cautious with his money now, except that he’s a soft touch for the old has-beens of show business. He won’t talk about this, and I’d get in wrong with him if I went into detail, but plenty of hard-up actors and circus people know the facts. His interest in show business developed early in life. You might say he inherited it. When I was a young man, I used to win prizes on amateur nights at the local theatres for my song and dance routine called “The Broadway Swell and the Bowery Bum.” I played the accordion and the harmonica, too.

Burt got his acting start at the nondenominational Church of the Son of Man and the Union Settlement House, in our neighborhood. I remember his opening line well—too well! When he was three years old, he played a shepherd (wearing a burlap potato sack) in a Nativity pageant. Needless to say, he wasn’t assigned any dialogue. In the midst of the performance, he discovered he had chewing gum stuck to one shoe. So he sat down center stage and proceeded to pull it off. After much exasperated pulling, he snarled at the top of his little voice, “How’d this damn gum get on my shoe?” Mrs. Lancaster was not amused. She couldn’t wait to get her youngest off the stage.

But his career wasn’t ruined. In fact, he finally got promoted; for years, the Lancaster boys played the Three Wise Men in the Christmas pageant. It became a sort of tradition. Willie and Jim weren’t too keen about acting, but Burt got a big kick out of it. He was a movie fan, and at seven his great idol was Douglas Fairbanks. When “The Mark of Zorro” played the Atlas Theatre in our neighborhood, Burt was there when the doors opened at eleven. He was still there at eleven that night, forgetting all about lunch and dinner. Naturally, his mother was in a tizzy. “Willie,” I said, “go get Burt. Bring him home even if you have to use force.”

“Aw, Dad,” Willie complained, “all I ever do around .’here is retrieve Burt.” But he went and got Burt, and he used force, all right. This time, Mom didn’t have to administer a licking; Willie had beaten her to it.

All the same, Burt wasn’t the slightest bit discouraged. He’d go around the house jumping over everything in sight, trying to imitate the Fairbanks feats. It never occurred to me then that he’d eventually become an athlete; he was quite small as a child, and we figured he was going to be the runt of the family. Suddenly, at thirteen, he seemed to begin shooting up overnight, and turned out to be the tallest of the boys. (He’s six feet, two now, weighs 185 pounds and has a forty-one inch chest.)

Burt started on his way toward being a second Doug Fairbanks when he met an Australian fellow named Curley Brent, a neighbor of ours who taught him how to do a few stunts on the horizontal bars. This taste for acrobatics got my boy and his pal Nick Cravat so excited that they decided to build bars of their own. Burt borrowed money from me; Nick got some from his mother; and soon the two of them, the husky blond kid and the wiry dark one, were swinging away in our back yard. You’ve seen the same team, grown up, showing their skill in “The Flame and the Arrow” and “The Crimson Pirate.”

But I couldn’t foresee this, so I was pretty exasperated with Burt, some years later, when he left college and went off with Nick to join a circus—at three dollars a week apiece! If his mother had been alive at the time (she died when he was fifteen), I don’t think he would have made this break. Mrs. Lancaster was set on the children getting college diplomas, and the other three did. Probably, my own old-time interest in show business kept me from trying too hard to talk Burt out of turning acrobat. Whenever a circus or carnival including his act came within twenty-five miles of New York, I’d always go and see him. Burt doing giant swings and somersaults was really something. But I couldn’t help thinking that his mother wouldn’t have liked it.

Of course, Burt still keeps in top athletic trim even while he’s working on a picture that doesn’t call for any stunts. (Being a frustrated actor myself, I’m extra proud of the dramatic job he does in “Come Back, Little Sheba.”) He has horizontal bars at his home, works out on them regularly.

In the last couple of years, Burt’s been far away from home a good deal, making pictures on location. The business of ranging from Ischia to the Fiji Islands reminds me again of that little towhead. I sympathized with Willie’s complaint about all the time he spent “retrieving,” because Burt could get lost easier than any kid I’ve ever seen. When the postal employees and their families had their big yearly clambake at Coney Island, Burt always got lost, and Willie always spent the day trying to find him. Burt’s wanderings were mostly due to his great curiosity. As a kid, he was interested in everything. Still is. I guess I’ve heard him say a million times, “But I want to know why.”

For me and the rest of the family, his travels can often be unnerving—like the time early in October when a Fijian native’s misaimed spear gave him a gash over the right eye, while he was working on “His Majesty O’Keefe.” But his wanderlust seems to be unsatisfied, and we all know better than to try tying him down.

When I say “the family” now, I mean my daughter-in-law, Norma, my remarkable grandchildren, Billy, Susan and Joanna, and step-grandchild, James, Norma s son by her first marriage. A few years ago, Burt persuaded me to come out and live with them at their West Los Angeles home. William has died, but his widow lives near us. Jane and Jim are still in New York, Jane teaching school and Jim on the police force.

While I’m not sure what Burt’s mother would have thought of ali his globe- trotting and the devil-may-care stunts he does in line of duty, I do know that his marriage would have made her very, very happy. When he was in his teens, he never seemed to bother much about girls, but I suspect he made up for lost time later, after he’d left home. Certainly, there was nothing bashful in the way he went about courting Norma. They met during the war in Pisa, Italy, where Burt was with the Army and Norma Anderson with the USO. And they must have been really taken with each other, because when Burt was ordered back to Florence and Norma to Rome, she smuggled herself into a plane and hopped out at Florence to meet him. The M.P.’s caught up with both of them; Burt got guard duty; the USO authorities confined Norma to quarters for three weeks. But this opposition only made them more sure that they’d eventually be Mr. and Mrs. It was just like Norma to insist on packing up the three older children and going along on his recent jaunt to the Fijis.

Yes, this daughter-in-law of mine is exactly the right wife for Burt, and he knows it. Not that they think alike on everything—Norma usually seems to take life lightly, is full of laughs, while Burt’s essentially a serious-minded guy, inclined to get intense about ideas and situations. He always has been a dreamer; when he was a little kid, he could be off in his own dream world for hours, and he wouldn’t hear a thing you’d say to him.

Because of some of the parts he plays in pictures, people get the notion that he’s a rough sort of bum who shaves with a blowtorch. Truth is, he’s always been crazy about books and music. As a boy, he belonged to both the 110th Street and the 96th Street libraries. His mother would tuck him into bed at nights, and he’d give her a big loving kiss and pretend to settle down to sleep. But she’d hardly closed the door before he’d have the bed covers pulled up to hide a flashlight and a Frank Merriwell book, and if he wasn’t caught at it he’d be likely to read away until daylight. Today, I’ll bet Burt is one of the best-read actors in Hollywood. He keeps up with all the important books, and he’ll sit up all night reading if something catches his interest especially.

Even as a small boy, he loved symphonies. Many a night I’d come home from my repairing chores and stumble over a body stretched out on the living-room floor. There would be Burt, listening to a symphony. We had a cabinet-model radio, and he’d turn it down low and stick his head under it so the rest of the household wouldn’t be kept awake. Later, when he was making a few bucks here and there, he went to the Lewisohn Stadium concerts regularly. When he was eighteen he took voice lessons, but soon decided to stick to listening. Opera’s another interest of his; he talks about it like a real long-hair.

These evenings, I come into the living room carefully to avoid tripping over the same body (slightly bigger now). Burt still stretches on the floor to listen to the record player. His tastes have spread out; he likes light opera, tunes from musical shows and all kinds of good jazz, as well as classical stuff. He sings just for fun, kidding about his voice.

Burt and Norma are stay-at-homes, I’d say. He enjoys catching a ballet when there’s one in town, and Norma likes to go to the movies a couple of nights a week. If it was easier for her to get Burt into dress-up outfits, they’d go to more big parties than they do. Their own style of entertaining is never extra fancy. Norma can toss together a dinner for anywhere from four to fourteen people without making a fuss about it. Burt always takes

over in the salad departman’s Caesar salad’s the specialty of the house.

They’re great meat and spaghetti eaters, and I’m not surprised that they go in for substantial food. Burt wasn’t brought up to be finicky; his mother saw to it that all the children ate what was put in front of them, and she never had any trouble persuading our youngest to polish his plate. So friends get a generous spread at the Lancasters’ when they drop in now.

A lot of these visitors are circus and carnival people who knew Burt when. And I guess you know who Burt’s best friend is—same kid I used to see out in our back yard with him, doing stunts on the horizontal bars. If Burt, boy or man, has been hard to get along with, Nick Cravat certainly doesn’t know it, any more than I do.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1953