She Had To Be Me

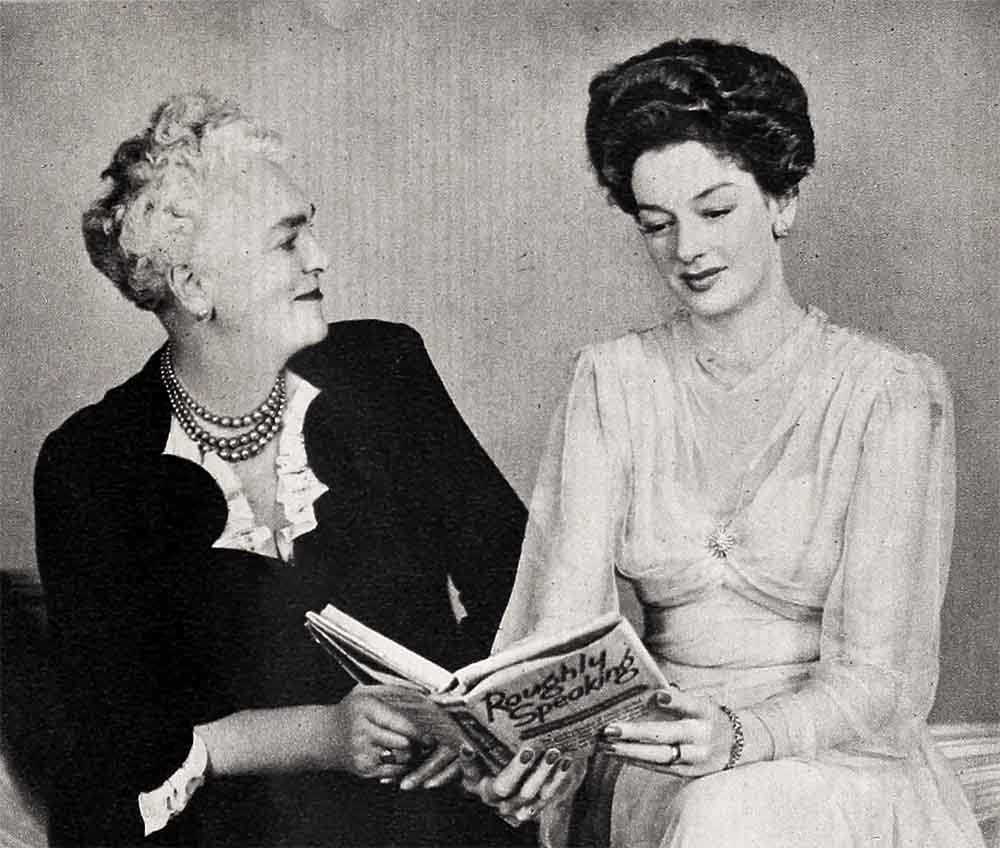

I’d been at Warner Brothers two weeks, working on the screenplay of my autobiography, “Roughly Speaking,” when Henry Blanke, the producer, came into the office with the news that Rosalind Russell was coming over to the lot to have lunch with us.

As this was the first time in the fifty-four years of my life that I’d been within spitting distance of a screen star, I was pretty excited. all I really knew about Rosalind was that she was a top-drawer comedienne, that she hailed from New England, as I did, and that she was mad about big hats.

Feeling that something drastic was called for, I dashed over to the drugstore and bought some wave set, which I applied so lavishly that in no time I looked like a stand-in for a drowned rat. Then I drew black rings on my white slip right under the cigarette holes in the old rayon number I was wearing and they wouldn’t have shown at all if there hadn’t been a high wind.

At 12:00 the phone rang with the news that Miss Russell was in Mr. Blanke’s office. At 12:02 I arrived breathless with the cold sweat running down my hands. As I entered, a tali, slim, handsome girl in a checked suit with a huge Chinese straw hat and bag, rose and came forward.

“You look exactly as I expected you would,” she said.

That remark is typical of Rosalind Russell. She is the least self-conscious person of fame I’ve ever met. She’s always more interested in her family, friends, fellow workmen and employers than she is in herself.

By the time lunch was over, Rosalind had allowed as how she wouldn’t mind playing me in “Roughly Speaking.” And I had decided if she didn’t play me, the rest of my life wouldn’t be worth living.

“I hate to introduce a sour note into this mutual admiration meeting,” said Mr. Blanke, “but you’ve both overlooked one little trifle—the script isn’t written yet.”

“But it will be,” I said with the sublime confidence of inexperience.

There were some bad hurdles to take, but before a month had passed, Mr. Blanke, with infinite patience, had beaten the facts of screen life into my thick head. Once in a while I would have a relapse and have a character rise from his chair before he’d even sat in it, but my secretary fixed that.

Finally, four months later, the script was actually done and mimeographed. I was so impressed to think I had written it that I couldn’t do anything but sit and look at it for two days. I suggested to Mr. Blanke that when my name appeared on the screen as author we add a little note to the public: “Don’t be too critical. It’s a heck of a lot harder to write a screenplay than you think it is.” But for the first time in my long and spectacularly unsuccessful life, luck was with me. Everybody seemed to like it, including Rosalind.

I could hardly wait for the first days of shooting. I visualized the star sweeping up to the studio about 11:00 in a limousine driven by a liveried chauffeur. And I had some vague notion of silver fox coats, orchids and possibly a footman following with a wicker basket of champagne. So I was pretty disillusioned when Rosalind drove her car briskly onto the lot at 7:00 a.m. and jumped out simply clad in a bandana, cotton shirt and slacks.

Rosalind, I might mention here, is always on time. She gets up at the ungodly hour of 5:30 and is ready for her call, no matter how early. At night, after shooting is over, she stays and looks at the rushes and is home and in bed by 9:30 at the latest. If by any chance she gets home earlier, she plays with the baby or takes him for a quick whirl along the sidewalk in his carriage; still dressed in her studio outfit, I might add. When she’s not behind the studio lights, she’s just an old-fashioned wife and mother, not an actress.

After working with Rosalind on the set for three months, I learned that she was not only simple and unaffected, but enormously intelligent. She has brains and she uses them every minute. She doesn’t just learn her lines in a picture. She studies them. And if she thinks a speech is illogical or out of character, she says so in no uncertain terms. But she’s never arbitrary. She expects you to come back at her with your rebuttal hot and heavy. If your reasons are convincing, she says, “You’re right. I’m wrong.” And there are very few persons, stars or otherwise, who are big enough to do that.

Not only does Rosalind put her mind on the script, but she studies the sets, camera, rushes and cuts. Mr. Michael Curtiz, who directed “Roughly Speaking,” said he never had such cooperation and so many helpful, constructive suggestions from a star in all the sixty-three pictures he has directed.

One of Rosalind’s pet phobias is that she will be expected to look young and beautiful at the expense of the story. In the last sequence of “Roughly Speaking” she plays me at the age of fifty-two. When she came on the set her hair was so white and she had so many lines in her face I was horror-stricken. But before I could sound off, she looked at me, and

then in the mirror. “I look much too young,”” she said to the make-up man firmly. “Make the chin sag some more. And lots more lines in the forehead.” I crept dismally off the set and looked into the mirror. She was right! Fortunately, there was nothing they could really do about her eyes, which are very beautiful, so I was really lucky. But it was days before I recovered.

The fact is that Rosalind, like most New Englanders, is a perfectionist. She is exceedingly critical of everything, including—and this is unusual in stars—herself. As I have a jaundiced eye which I can tum inward, this often led to a very frank but bracing exchange of dialogue between us. I remember one night in the projection room when we were looking at rushes which were not as awe-inspiring as we had expected. When they were over, Mr. Curtiz said gloomily, “Well, what has anyone to say?”

“Maybe we should throw the script in the ash can,” I suggested.

“No,” said Rosalind quickly. “It was I who gummed it up.”

There were murmurs of amazement from the others in the room, who were less used to frankness than they were to alibis.

Besides simplicity and honesty, Rosalind’s most outstanding characteristic is her sense of humor. It never flags and it lightens many a weary grind on the set. If there was a piano, she was never too tired to brighten the corner with her torchy rendition of “Old Man River,” or while away the time while the set was being lighted with a little close harmony with the grips. “Democratic person if there ever was one,” was the crew’s decision.

Her greatest fault is that she never rests . . . she burns up her energy every minute of every hour. If there were visitors on the set—particularly service men—she’d snatch time between takes to order root beer and have chairs brought for them. She was so interested in them that no matter how shy or awe-struck they were, in no time she’d have them telling her the story of their lives. At noon, after a quick lunch that wouldn’t keep a bird alive, you could hear her in her dressing room typing out letters to her brothers who are fighting, and of whom she is very proud. Then while the hairdresser would be putting the finishing touches to her hair, she’d telephone the order to the grocery man just like any housewife.

In her dressing room, incidentally, beside the pictures of her husband, Major Fred Brisson, and her son, Lance, there is always a gorgeous vase of roses. And there are always roses in her bedroom at home. They are her favorite flowers and I imagine that is why the sequence in “Roughly Speaking,” where she and Jack Carson “break” the market with too many roses and lose the greenhouses on which they have staked their all, touched her deeply. I saw her just after she played the scene and she could hardly talk. Her voice was hoarse and her eyes were red.

“Where did you get that horrible cold?” I said, shocked.

“It’s not that,” she half-sobbed. “But losing all those lovely roses . . . I can’t help bawling.”

Which all goes to show that Rosalind Russell is essentially a human, down-to-earth person. And I think that if the film proves to be a success, it will be because of this—as well as the magnificent performance she gives.

After all, she had to be me. And I was no angel. I was a woman who went barging through life trying to get the best for myself and my kids—making mistakes—usually winding up behind the eightball.

To play a part like that, you have to know people and like them; understand and sympathize with their hopes and struggles. And that’s Rosalind. Not only is she tops as an actress, but more important—as a human being she’s colossal.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1945