Return From Nowhere—Guy Madison

Contrary to the prediction made by Hollywood almost ten years ago, Guy Madison does not live in oblivion. In those days people said his popularity was a freak in show business, that his appeal was based only on the fact that he was young and handsome. They said that since he couldn’t portray emotion much more effectively than a wooden Indian, his burst of fame would shortly dwindle away.

The prophecy came close. Guy’s wave of publicity subsided, he dropped out Of sight, and for a long time hardly anyone knew what had happened to him. Then last summer Warner Brothers gave him a contract which pays him $100,000 per picture and guarantees him at least five pictures at this remarkable salary. The brass hats who run movie studios have been known to make costly mistakes, but the promise of a half million dollars for the services of one young man implies confidence backed by solid reason.

The reason is Guy himself. He is different from the boy of eight years ago, but he hasn’t lost his appeal. Gone is the roundness, the stolid muscularity of the curly-headed youth who attracted thousands of bobby soxers during the last years of the war. Guy is thinner, harder, a powerful man of thirty-one. His face is lean and his body has matured into a lithe suppleness. On the surface his personality has changed very little. He is even more taciturn, limiting his conversation to terse “yups” and “nopes.” Outwardly, he is developing into a young edition of Gary Cooper, with the same quiet appeal of a man who is happiest out of doors.

Naturally, there is more to Guy than meets the eye. In these last years he has learned that life is a difficult and exacting school. There is an old wheeze in the theatre that a man must have suffered in order to-be an actor. Guy is living proof. He not only has the Warner contract in his pocket, but also the Wild Bill Hickok show, on radio three times a week and on television every Sunday. The long climb back to the, top has been difficult for him, yet it is perhaps because of it that Guy has found his niche in acting.

At the beginning, it wasn’t easy for him. His picture on the cover of a Navy magazine attracted the attention of an agent who eventually interested David Selznick in the young sailor. Guy was given a role in Since You Went Away, appearing in his Navy uniform for three minutes on the screen. The three minutes were enough to bring tons of mail to the studio, inquiring about the “handsome new actor.” The Selznick studio immediately went into action, giving the youngster a class A (colossal) publicity buildup.

If they weren’t prepared for such an overnight sensation, neither was Guy. He had never given acting a thought and knew nothing about it. He had thought he might go into forestry after the war. And here he was, suddenly made a star by public pressure, and soon afterward bumped into a leading role opposite Dorothy Maguire in Till The End Of Time. It was a frightening experience for him, shouldering half the responsibility of a top budget picture along with a star of experience and magnitude. He knew that he was becoming the butt of jokes around town. ‘As good as Guy Madison’ became a standard gag, and Guy tried to shrug it off. “What am I supposed to do?” he asked. “If they want to give me the work and pay me the money, I’d be crazy to turn it down.”

Despite his wooden performances his popularity increased, and along with Frank Sinatra and Van Johnson, Guy became the idol of the teen-agers. He had hit the movies at the right moment. Most of Hollywood’s actors were away in the service, and those who weren’t needed 4-F papers to excuse themselves for being loose. Guy was in the service, and therefore a double-dyed hero. He was exceedingly good looking, and twenty-one, a proper age for the adulation of girls whose lives were so empty of young men.

He was loaned to RKO to make Till The End Of Time following his discharge from the Navy, and then to make Honeymoon with Shirley Temple. Selznick never used him in a picture after his brief appearance in Since You Went Away, but instead cashed in on him as a popular property. Possibly Selznick knew how unprepared Guy was for starring roles: and preferred to let other producers take the chance. At any rate, Guy was released in 1947 from his Selznick contract. On his own, he found that the going was not easy. Producers had seen him struggling with his lines and concluded that Guy Madison was, after all, only a flash in the pan.

Guy had mixed emotions about it all. He figured the publicity was still heavy enough to insure future movie roles, but if anything drastic happened, he thought, he could always go into commercial fishing. He hadn’t asked to be let in, and now if they wanted to let him out, he could find something else to do. But in his heart he wanted the movies to be his livelihood, and braced with optimism, he married Gail Russell in July, 1949, after a courtship of three years. That the two were deeply in love no one doubted but in April of the following year they had their first spat. There was an argument at a party, after which Gail moved to an apartment and Guy went hunting. “He always ‘goes hunting when he wants to think,” she said when they were back together again. The rift lasted only a short time, but it was the first indication that all was not well with their marriage.

At that time, Guy had been a year without work, and shortly afterward Gail asked to be released from her contract with Paramount. Gail never wanted to be an actress, any more than Guy wanted to be an actor. Her sultry beauty had been discovered while she was in high school in nearby Santa Monica, and she had been booted to stardom, much as Guy had. Both of them, but especially Gail, lacked self-confidence. After years of leading roles she left Paramount. It was a move that helped their marriage. But Guy wasn’t doing well. He did theatre work around the country and made a few pictures for independent producers, notably Red Snow and Drums In The Deep South, but without the backing of a major studio these films were scarcely noticed.

In 1950 a pilot test film was made of Wild Bill Hickok, with Guy in the title role. The series was planned for television, but as is true with every TV program, it took time, and lots of it, to find a sponsor. Because the show might be sold at any time, Guy couldn’t make other commitments, and the doldrums made a lean and hungry period of waiting.

Ironically, this was the period during which Guy, for the first time since finding himself within the gates of Hollywood, had confidence in his own ability. During the years of erratic employment he had been working with dramatic coach Eda Edson, who after talking with him two hours gave him his cue. Guy was not an actor, per se, but he had the makings of an excellent performer. And so Miss Edson told him, “To thine own self be true.” That was a valuable bit of advice for Mr. Madison. He began to realize that if he felt out of place wearing a tuxedo in real life, he would be unconvincing in a tuxedo on the screen. He learned that if he wanted to be a success in Hollywood or in the theatre, he must seek out roles he could understand, parts in which he could react naturally. It is a method that has paid off handsomely with many of Hollywood’s top performers—John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Esther Williams—the list is endless. Guy had his cue, at last, and chafed with impatience for the chance to prove himself to his former critics.

When Gail went home from Paramount to be Mrs. Madison, the budget was taut. Guy’s income was sporadic, yet his new confidence gave him the courage to hang on and wait and hope.

Perhaps all would have worked out had it not been for Gail’s tragic addiction to drinking. It was a habit brought on from long years of insecurity and a childhood that left much to be desired. Gail was, and still is, one of the best-liked girls in town, and her friends have understood the fact that she was a sick girl much in need of help. Modern medicine has proved that the alcoholic is not to be blamed, but rather the circumstances which have led him to drink. From those who knew her peace and peels for Gail in her battle to conquer the habit. She tried hard, with Guy at her side to do all in his power for her.

This sort of thing is tough on any marriage. With this friction, their incompatabilities began to show more each day, and soon Hollywood was speculating on how long the marriage would last. No one wanted to see it break up, as both Gail and Guy, despite their retiring manners, were liked and respected even in the extrovert town of Hollywood. People knew they were in love, but there was trouble. Their friends were not surprised when they separated a year ago.

In the time that has since passed, they have remained the best of friends. This is a speech worn thin by Hollywood divorcees, but it is true of the Madisons. They have deep feeling for each other, but they cannot make a go of marriage, and have given up trying. The decision wasn’t made without a great deal of effort. Only last August Guy said in one of his rare statements to the press: “I admit I am heartsick over our separation, but for various reasons we can’t seem to make a go of it. I am still devoted to Gail and anything she needs from me she will always have. I have only appreciation for the wonderful years she made possible. I have no regrets. After all, ’m lucky—I had the chance to experience a strong and honest emotion.”

At this writing there is no legal separation but chances are that Guy and Gail will make the situation legal, either by separation or divorce. Whatever happens, there will always be a bond between them, and Guy’s continued support of Gail, acting still as a pillar of strength to bolster her extreme insecurity, is one of Hollywood’s most admirable stories. Whatever happens, both of them have the respect and good wishes of the whole town.

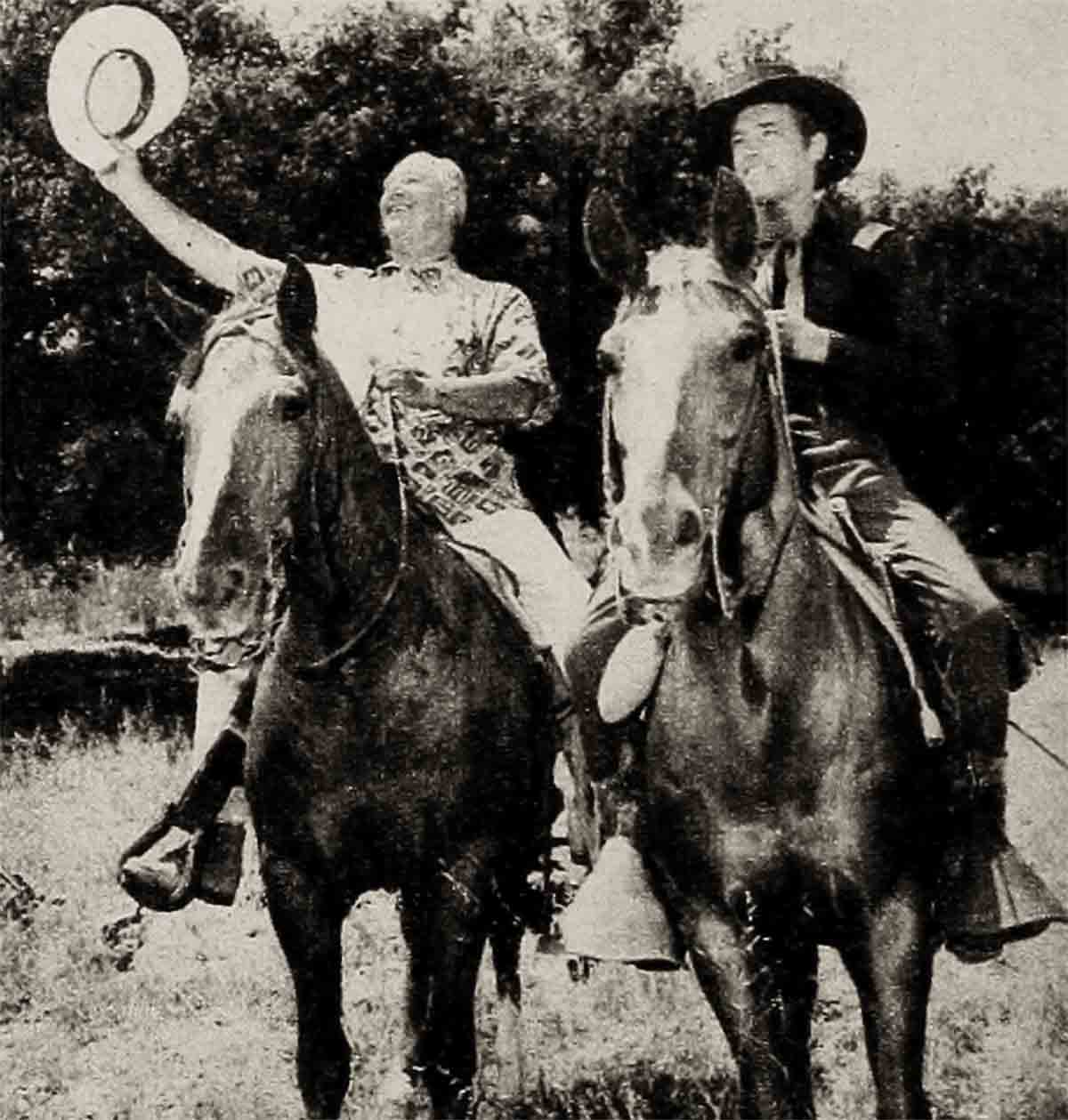

By the time the Madisons had separated Guy had become known once more to the public, this time through his tv role of Wild Bill Hickok. It had been rolling for a year, and Guy in buckskin was a familiar sight to the kids of America. Many of their mothers, seeing him ride across the screen in their living rooms, remembered the days when they too had been fans, and felt a renewed interest.

The Hickok role brought him his chance for a movie comeback. During the first flaring of 3-D fever, Warner Brothers studio planned a batch of these films and one of them, to be called Charge At Feather River, was hurriedly prepared for production. The stumbling block was the casting of the leading man. Gary Cooper, John Wayne and many of the screen’s outdoor men had been approached but none of them could take the role because of other commitments. Only one week before start of production Warner executive Steve Trilling mentioned the problem at home. His eleven-year-old daughter said, “Why don’t you get Wild Bill Hickok?” Trilling took his child’s suggestion, and Guy was brought to the studio.

His performance in Charge At Feather River surprised everyone, not the least of whom was director Gordon Douglas, whose serious reservation about Guy changed to astonishment. After working with him a few days, Douglas saw to it that the script was strengthened to give full play to Guy’s surprising new ease before the cameras. Television experience had made movie work much easier for him, and he stuck to his cue from Eda Edson and acted like Guy Madison would act. It was important, too, that Guy’s new job came only two weeks after his split with Gail. To erase his unhappiness he dedicated himself to doing the best job possible, and as a result the press did nip-ups of surprise the night the picture was previewed. As one young fan put it in a letter to Guy, “I have seen all your TV shows plus Charge At Feather River. My big sister said she didn’t think you could make love until she saw you in that movie. Now she says gee.”

Guy’s appealing love scenes were only a small part of his charm for his new-found public. They discovered another quality—the lithe, panther-like way he moves. Director Douglas told him, “You give the most beautiful action since Tom Mix,” and director David Butler has nicknamed him “The Cat.” Women were quick to notice this agility, and the fan letters once more poured in for Guy, this time more than 3000 a week.

His appeal stems from the fact that he is a man’s man, and therefore a woman’s man, too. He is quiet, not in the shy way of ten years ago, but in the way of a lone wolf. He is the kind. of man who gets along more easily with children and animals than people his own age, and greatly prefers conversation with a man to that with a woman. Still ill at ease among strangers, he doesn’t talk much when he’s with a crowd. Some say Guy wishes he could unbend, but he doesn’t know how. He has been known to be closely associated with people for more than two years before they feel they have broken through one small part of the wall that surrounds him.

Without knowing what he is thinking or what makes him tick, they do know he is generous, thoughtful and sincere. He is completely unaffected, deeply sensitive, and has a horror of hurting people’s feelings, though he hides the sensitivity and shies away from obvious sentiment.

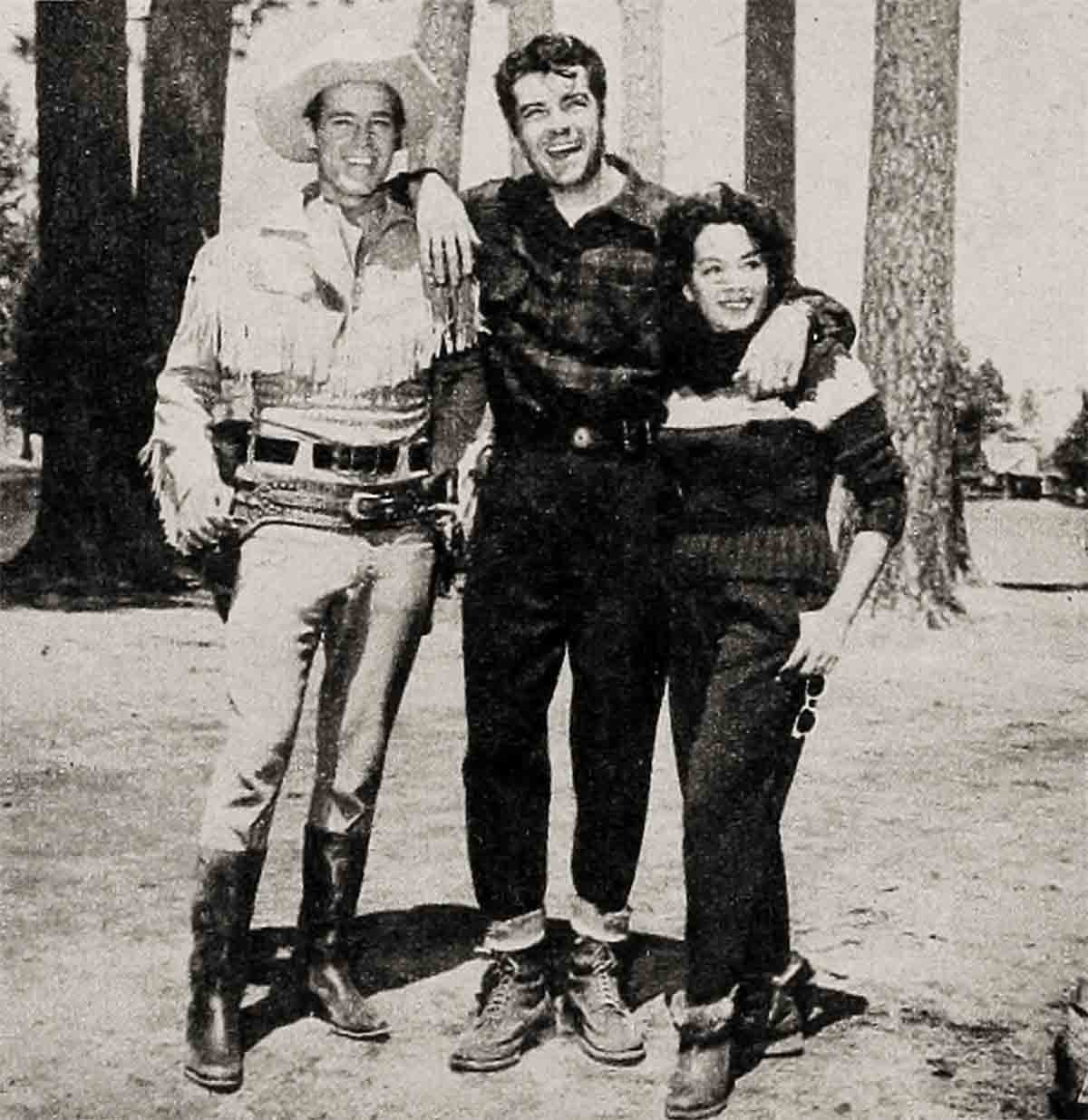

His thoughtfulness is shown by his refusal to help his brother break into movies. “There are too many people out of work in town,” he told Wayne. “If I went in and pitched for you it would only create resentment.” Instead, Guy invited his brother to visit him at the studio, and when his directors saw Wayne they put him to work as Chad Mallory.

Guy thinks nothing of appearance for appearance’s sake. He drives a pick-up truck “because it’s useful for hunting, and for the rest of the time it takes me where I want to go.” He has been criticized for wearing his cowboy clothes around town. “Guy Madison is taking the Wild Bill Hickok thing too seriously,” was a typical comment. The reason was that Guy had no other clothes. One afternoon he kept an appointment at a swank restaurant with Louella Parsons. He had come directly from work, wearing a dress cowboy outfit, and somebody said they wished he had taken time to go home and change into street clothes. “I wish I could,” said Guy, “but I don’t have a suit. I’ve been too busy to grab time to buy one.”

He pals with men who also shun the elegant life of Hollywood—Rory Calhoun, Andy Devine and Howard Hill—with whom Guy often goes hunting with bow and arrow. It remains his chief interest in life, besides his work, and because of these two things Guy is seldom home. He lives in a small Westwood apartment which is sparsely furnished. The living room contains only a television set and his archery equipment. He sleeps and showers at home, and sits on the floor to watch television. He eats at the homes of friends or in restaurants and doesn’t even make coffee in his kitchen.

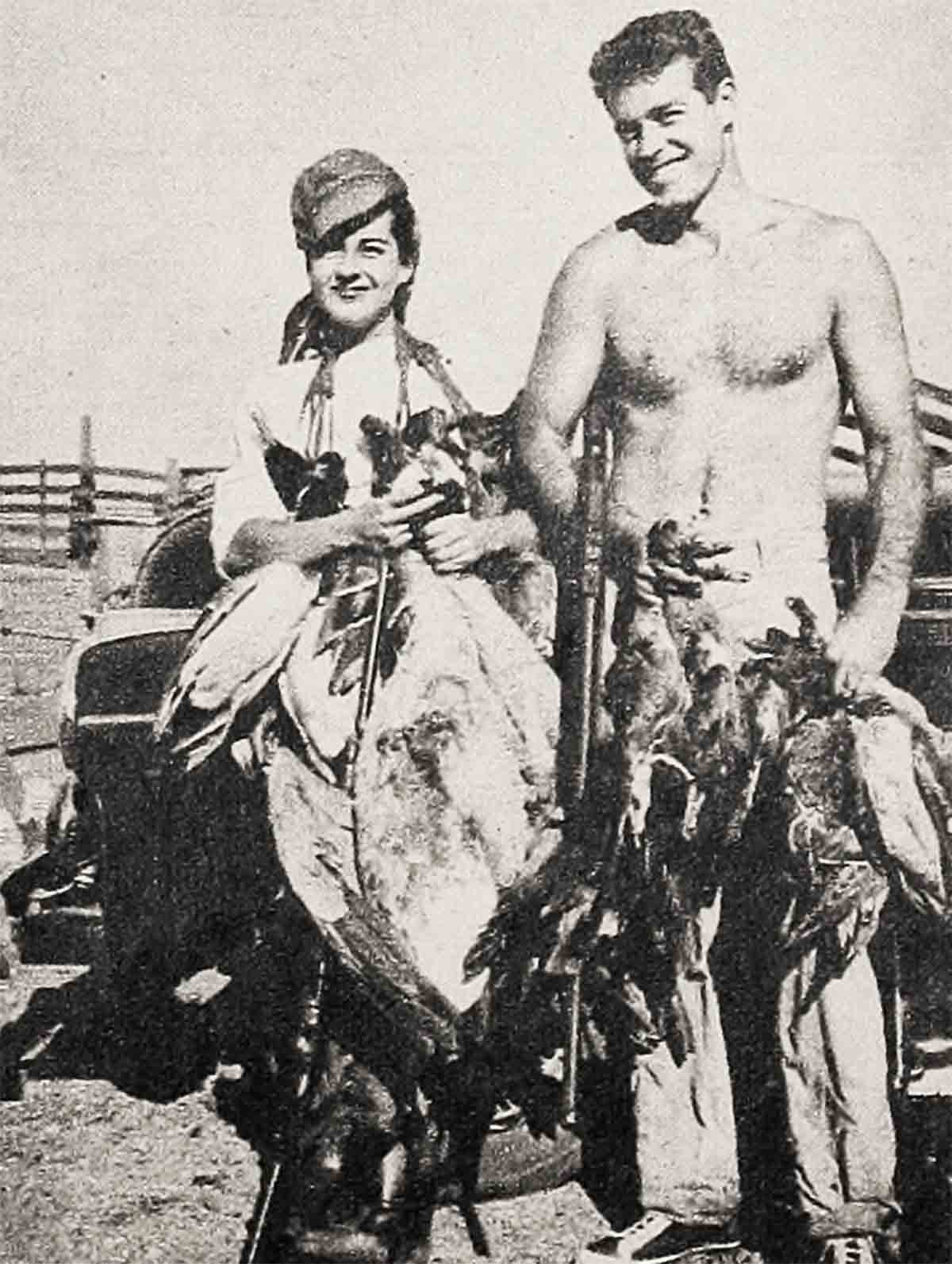

He has a new respect for money—“A couple of bad years taught me”—and his way of living allows for a nest egg which he hopes to apply some day to the purchase of a ranch up near Marysville. “Some people spend money on Cadillacs,” he says, “but I probably put just as much into hunting. It’s more important to me.”

Last November he went on a month’s hunting trip in Idaho, packing in twenty miles up in the mountains, and except for eight free days in the previous six months, this was his only time off. Guy devotes himself to his work and allows little time for living. Now that he is so earnest about acting, he is showing a surprising understanding of plot, script and dialogue. After reading the script for The Command, his second film for Warners, he wrote producer David Weisbart a letter which began, “It’s been my experience that to come across believably I have to be able to believe that I, personally, could act and react the same way as the character I am playing.” He followed with ten suggestions, including long scenes full of dialogue. The studio considered his changes valuable enough to be incorporated into the script.

“I’m not inclined to try sophisticated roles,” he says now. “Before, I went too far too fast and had roles beyond my capacity with the result that my work wasn’t up to my publicity. I don’t go for false publicity. I think it should be angled according to what you’re trying to accomplish.

“From now on I’m going to concentrate on Wild Bill Hickok on the radio and TV, plus the movies for Warners, and I’m free to produce one picture a year on my own.”

This is a long statement for Guy Madison, but it neatly summarizes his plans. It shows a man who is devoted to his work, certainly through deep interest and careful training and possibly because of heartbreak. The last five years have been full of pain for both Guy and Gail, but out of it all each has found some happiness. Gail is doing what she has always wanted to do; she is using her remarkable artistic talent to illustrate a book. And Guy has come into his own as a performer who, from the look of things, is here to stay, this time.

THE END

—BY ROBERT MOORE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1954

No Comments