Pat Boone Adopts Ten (yes, 10!) Boys

“Yes, I’ve made up my mind. I’m going to adopt nine—no, ten—boys,” said Pat Boone. I was so startled that I took my eyes off the diamond at the Polo Grounds, where the New York Mets were being clobbered by the Chicago Cubs. I stared at Pat—but I’d never seen him more serious. So I mumbled the only thing I could think of. And stupid, too. “Well, which is it—nine or ten?”

“Ten. If it works out all right, we’ll adopt the others later on.”

I actually stammered. “Your wife—Shirley—she is in favor of all this?”

“Sure,” Pat said. “She hasn’t met them yet—but we’ve both wanted boys for so long, to give us a balanced family! After all, we’ve got four daughters. Shirl will be delighted.”

“I’ll bet,” I murmured dubiously.

“You know, we made arrangements a while back to adopt a boy,” Pat continued, never taking his eyes off the action on the field. “A young girl had contacted us—she was divorced and couldn’t support the child she was expecting. So we offered to adopt it. Well, it was born—right on my birthday! But everything got fouled up. Instead of being a boy, it was a girl. And at the last moment, when she held that little infant in her arms, the young mother decided she wouldn’t—she couldn’t give her up. We were very glad she made that decision. Still, it was tough on Shirl.”

“But won’t it be a lot tougher on Shirl to take care of ten boys than of no boys?” I asked.

“Oh, we’ll make do,” Pat answered. “We’ve got a five-bedroom house, but still, we’ll have to double up. There’s a big playroom upstairs where the boys can fool around. It’s almost big enough for them to play baseball in. If they can’t catch or field the ball the first time, they can always get it on the rebound off the wall. My daughters—Laurie, Debbie, Linda and Cherry—can play, too, they can hit grounders and flyballs to them. And if the boys really knock themselves out playing ball, we can always convert part of our swimming pool to a whirlpool bath. That’s the best thing there is for sore arms, you know.”

“But what if some of them are the bookish type and get tired of athletics?” I asked.

Pat wasn’t fazed. “We have a prayer room or a meditation room or a crying room—whatever you want to call it,” he replied. “The oldest boy—the tenth one—he’ll probably use it a lot.”

Suddenly, Pat jumped to his feet in the box and yelled, “Let’s go, Mets!” A Met batter streaked down the base path and made it safely to first. “Hey, ya creep, down in front !” a guy in back of him yelled. But Pat just shouted, “That’s my boy. Go!” A minute later, the next Met batter popped out and Pat slumped back in his seat. “They’re better than they think, better than they play,” he said sadly, waving a Mets banner at them.

But I was still stunned by the news that Pat was adopting ten boys. I didn’t even have the sense to ask him who they were, or through what agency he was adopting them. Instead I mused, “Ten boys, hmmm. Statistically, then, a few of them will have the same trouble as the players out there—lack of confidence. What’ll you do about that? How will you help them solve that problem?”

“A few of them!” Pat echoed my words. “All of them! And I’ll handle all of them the way we do our oldest, Cherry. She’s ten. And when she plays the piano in a pupil recital, she’s got to be the best—if she hits a wrong note, you’d think she was Mickey Mantle striking out with the bases full. I told her, ‘Look, Cherry, if you make mistakes, it only proves you’re human. The main thing is to do your best.’ Which she did, and the applause was all the greater because she wasn’t perfect—she made fluffs but she didn’t let them throw her.”

“And the same technique will work for your—your sons—if they lack confidence?” I inquired, wondering a little.

These kids have problems

For the first time, Pat Boone turned his gaze away from the diamond—where the Mets second baseman had just muffed an easy grounder—and looked directly at me. There was a tinge of sadness in his voice and he said, “Well, I’m not sure. It doesn’t always work. And with the kids I’m adopting . . .”

“There’s—there’s something wrong with them?” I asked, not knowing just liow to phrase the delicate question.

“Not wrong, exactly,” Pat said softly. “It’s just that—well, I guess you’d call them kind of underprivileged.”

“Slum kids?”

“Worse than that,” Pat explained. “They’ve spent all their lives in the cellar! They just don’t know what it’s like, not being on the very bottom. Not that they aren’t good kids—it’s just that they don’t know what it’s like to hold up their heads and win. They’re scared. You can’t even call them losers. They’re habitual non-winners.

“They remind me of April Love—the horse, not the picture. My friend, actor Arthur O’Connell, and I bought this colt together, and we immediately named him April Love. He was a beaut—good blood line, fine potential speed.

“Arthur made the trip from New York to Lexington, Kentucky, to get him. He treated that colt like a baby—even slept with him in his stall. Arthur would pat him on his neck and whisper, ‘You’re going to be in races. We want you to win. But the main thing is for you to have a happy life.’ Like a father trying to give his child confidence . . . like me talking to Cherry before her piano recital.

“That first year, as a two-year-old, April Love was always far back in the pack. Our jockey reassured us. ‘All his energy’s going into growing. He’ll beat ’em all next year.’

“When next year came, the horse suffered a bone chip in his leg. We sent him to the beach at Malibu, and for six months he frolicked in the surf and sand. We’d whisper to him how good he was, explain that winning didn’t matter, it was just being in the race that counted.

“It didn’t work. All he got from those months of frolicking was a wonderful sun tan. Finally,” he added, “we sold him to rodeo star Casey Tibbs for one dollar.”

Before I could say a word, Pat rose to his feet, shook my hand, made arrangements to see me the next day and hurried off to Ralph Kiner’s post-game TV show.

Just like father and son. . . .

As he strode down the aisle towards the tunnel that leads under the stands, Casey Stengel, the Mets’ seventy-four-year-old manager, popped his head over the dugout and waved at Pat. For a second the actor and the septuagenarian huddled together, laughing, clasping each other affectionately—like father and son.

I hurried to a bar. I had to think. Ten boys. Pat Boone was going to adopt ten boys. And I’d been so stunned I hadn’t even come up with the right questions.

Two whiskeys later I was wondering whether it would be fair to Photoplay if I phoned the wire services and gave them the scoop. Naw, my first loyalty was to the magazine; after all, the editor was paying for my drinks.

Then I got skeptical. Maybe Pat had been pulling my leg. Maybe . . . but at that moment the bartender flicked on the TV set. And there was Pat repeating what he had just told me, that he was “adopting” ten guys.

Several drinks and ten hours later I joined Pat on the air-conditioned chartered bus that was taking him on a whirlwind personal appearance tour of theaters in Manhattan and surrounding areas in connection with the showing of his film, “Main Attraction.” Pat looked fresh and wide awake, not like a guy who was taking on the responsibility of bringing up ten additional children.

“You don’t look so good,” he said.

“I don’t feel so good,” I muttered. “But forget about me. Let’s get down to cases. Who are these ten boys you’re adopting?”

Pat blinked and said blandly, “You must be kidding. I told you all about them yesterday. And you saw me with the oldest boy.”

“The one who’ll use the meditation room to cry in?” I asked, biting again.

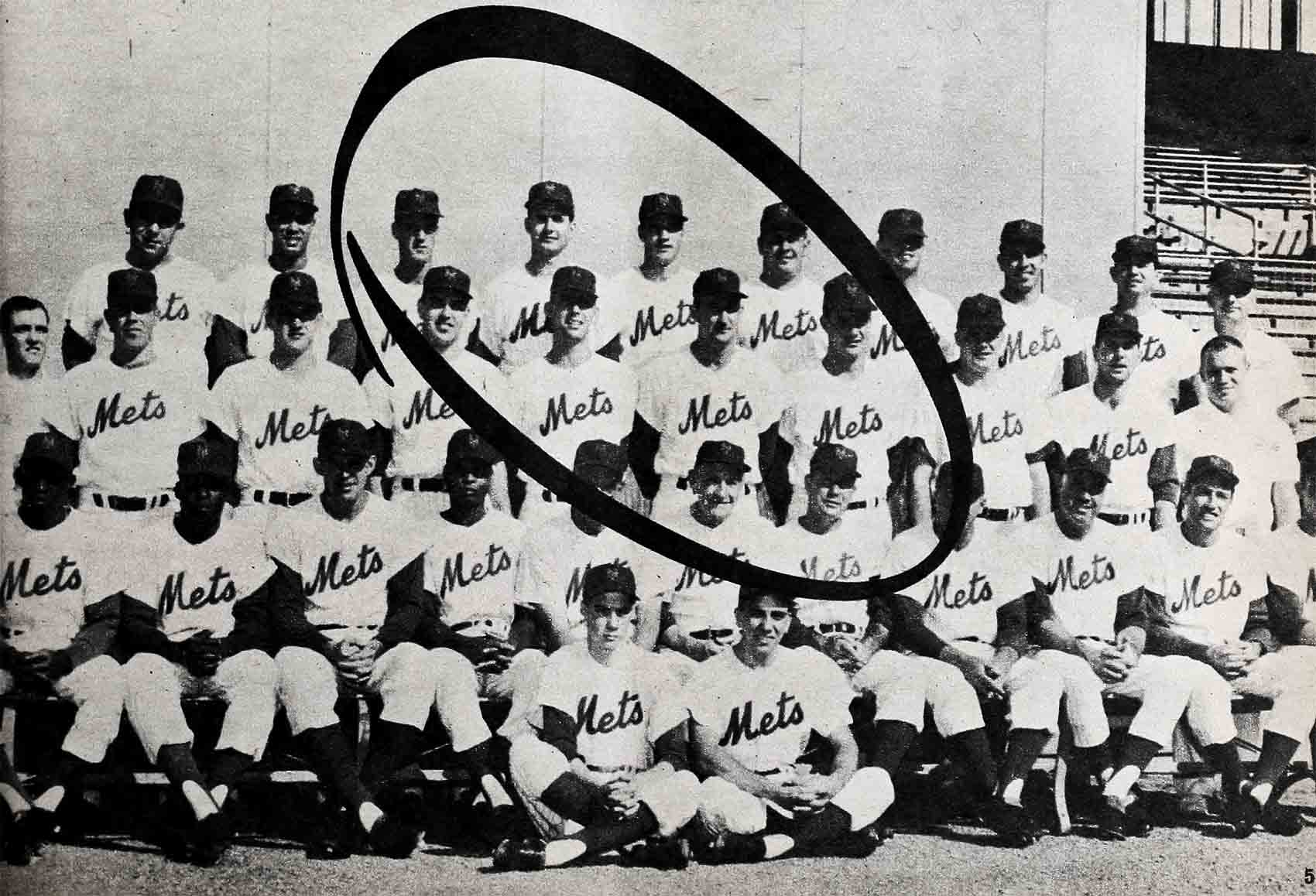

“Yeah. Casey Stengel.” And with this, Pat whipped out a team picture of the New York Mets and said proudly, “They’re my boys! Of course, I’m adopting only ten of them—three outfielders, four infielders, a catcher, a pitcher . . .”

“. . . and Casey,” I chimed in foolishly. Then angrily, I added, “But you can’t legally adopt them, and besides it’s all a hoax and . . .”

“Then I’ll do it illegally,” Pat broke in. “And it isn’t a hoax. I dig these boys the most. Didn’t you hear me tell Ralph Kiner all about it last night? Why I’d give my right arm if they let me work out with them and maybe let me take a crack just once at playing centerfield. In an actual game.”

“With one arm you’d be a natural for the Mets,” I said.

“What dya mean?”

“Why, they’re awful. The worst,” I snapped. “Look—right here on the sports page! Even Casey, their manager, mind you, admits it. He says, ‘I got some guys whose arms are okay, but their heads ain’t. If I could take the head from one and the arm from another . . .’ ”

“That’s Casey double-talk,” Pat laughed. “They’re not that bad.”

“You’re right,” I agreed. “They’re worse! They’re awful. Look, I’ve been collecting horrifying statistics and frightening stories about them—from the Columns, the sports pages, the obituary notices, even. And from books like Jimmy Breslin’s ‘Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?’ It all adds up to the fact that they’re a disgrace to baseball.”

Pat tried to interrupt me, but I wouldn’t be interrupted.

“Do you know that Bill Veeck called them ‘without a doubt the worst team in the history of baseball’? Do you know that Richie Ashburn quit the game saying that he’d rather commit suicide than be a benchwarmer for the Mets? Do you know that Joe E. Lewis gets his biggest laugh when he says, ‘I never drink to the Mets. I drink because of the Mets’? Do you know there’s a move on to tape their games like you do TV shows—so that their goofs and errors can be wiped out and once in a while the ending can be changed to let the Mets win one? Do you know that Dick Young wrote a column in which he said, ‘Most of the boys are playing as if their Blue Cross had lapsed’? Do you know that Bob Hope breaks ’em up when he quips, ‘I like the Mets. But I like baseball, too’?

“Do you know that sometimes when one of the pitchers is being shelled by the other team and Casey motions to the bull pen for a reliefer, no one responds because they’re afraid to come out? Do you know that Toots Shor, who loves everyone, says, ‘I have a son and I make him watch the Mets. I want him to know life. You watch the Mets, you think of being busted out, with the guy from the Morris Plan calling up every ten minutes. It’s a history lesson. He’ll understand the depression when they teach it to him in school’?”

“Words. Just words,” Pat said, not impressed at all. “Propaganda. Jealousy.”

What a record!

“Then I’ll give you statistics,” I snarled. “Straight from the record book.

“Last year the Mets lost the most games ever dropped by a major league club in one season—120. Their pitchers allowed opposition batters the most home runs in a season—192, while at the same time breaking the National League record for wild pitches—71.

“To be honest, it must be pointed out that the Mets did lead the league in certain departments: they gave up the most earned runs to the other teams—801 ; their pitchers hit the most batters—52; they committed the most errors—210; one pitcher, Jay Hook, gifted opposing teams with the most earned runs—137; another pitcher, Craig Anderson, lost 16 games in a row; and two of their pitchers, Al Jackson and Roger Craig, were 20-game losers.

“At the beginning of the 1963 season Mrs. Joan Payson, the philanthropic lady who owns the Mets, said, ‘Well, let’s hope it is better this year. It has to be. I simply cannot stand 120 losses this year. If we can’t get anything, we are going to cut those losses down—at least to 119.’

“Perhaps the definitive word on that disastrous first year came from Casey himself when, in the middle of the season, he announced in desperation: ‘I intend to trade anybody on this ball club. And we intend to start trying to make deals with other clubs right now.’ To which—according to Jimmy Breslin—the other nineteen teams in major league baseball chorused, ‘The hell you will!’ Anyway, after the Mets had fumbled their way through that final 1962 game, Casey said, ‘The public that has survived one full season of this team got to be congratulated.’ ”

“But you are leaving out the most vital statistics of all,” Pat said softly.

“What’s that?” I growled.

“In 1962 the Mets had the highest attendance in history by a last-place club—922,530. And I was, am and will always be a Mets fan. You might say I’ve been a Mets fan all my life. So I’m adopting them!”

“But why?” I persisted.

“Maybe Jimmy Piersall. the Mets outfielder, had the answer when he said on Johnny Carson’s show, ‘The Mets fans? They’re great. You know, they’re just like me. They’re sick. They’re lifetime losers.’

“Piersall knows what he’s talking about. When he hit the 100th home run of his career recently, he celebrated by running around the bases backwards. Later he said: ‘I just kept thinking, I hope I don’t fall down. Maybe I should have. It might have been funnier.’ Now he’s looking forward to getting his 1,500th base hit; then (and I’m quoting him) ‘I’ll just turn cartwheels.’ Meanwhile, I’m looking forward to seeing him try something else: a guy who says, ‘I still want to catch a ball with my hands behind my back,’ can’t be all bad.”

“But you’re on the top of the heap and they’re at the bottom,” I persisted, as the bus pulled up in front of a New Rochelle theater. More than a thousand fans were waiting.

Pat smiled and waved, then sat back and waited for the cops to clear a path to the stage-door entrance.

“Scratch any fellow who thinks he’s successful,” Pat said, “and you’ll find a Met underneath. For ten years, from the time I was ten until I was nineteen, I was a Met. I entered every talent contest in Nashville, local and national. I never won. I never placed.

“So I kept telling myself I was doing it just for fun. Yet, after I’d been knocked out of an audition in the first round I’d hang around, button-hole a talent scout and ask him for his opinion of my chances.

“Always I’d get the identical message, in slightly different words, ‘Forget it, kid. There’s nothing unusual about your voice. It’s pleasant, nice, but there are thousands of others just like you. Why knock yourself out? Give up.’

“But, like the Mets, I didn’t. Maybe it was pride, or curiosity, or force of habit, or blind faith or deep-down cussedness. But I still entered every contest.

“Then, out of the blue, I won a Nashville contest. I got a trip to New York and went on the Ted Mack show. And I won three times. Next was Godfrey—again I won. I was on my way. It was like the Mets sweeping a four-game series with the Dodgers.

“So I went back to Texas—I was going to school there—and Shirl was expecting a baby. For a year I auditioned all over Texas for every radio and TV station. Nothing. It was like the Mets dropping ten games straight.

“Finally, I got a job as a Fort Worth hillbilly—supposedly Texan. I was out of the cellar now with no place to go but up.”

The door of the bus opened. A police escort whisked Pat down an alley and into a dark corridor that led backstage.

In his dressing room, Pat picked up from where he’d left off on the bus.

“Everybody’s a Met”

“We all make goofs and blunders in our lives,” he said. “But if we play our heads and hearts out—like the Mets—we’ll still make mistakes, but eventually we’ll win. That’s why I root for them. I see myself in them—what I was. What, but for the grace of God, I might still have been. And what, for all I know, I may yet become again.

“The Mets are the eternal underdogs. The underest underdogs of all. The dachshunds of baseball.

“They’re like Leona Anderson, who calls herself ‘the world’s worst singer,’ like Fabian, who admits he can’t carry a tune; like those fumbling and well-intentioned goofs, Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin; like that ugly, swayback nag. Silky Sullivan, who sometimes, somehow, came through to win; like Rocky Graziano, who had trouble with the law and yet fought his way back; like Jack Paar and Ed Sullivan who, because some people call them ‘no-talent’ guys, win everybody’s sympathy and support.

“They’re like everybody. Like you and me. That’s why the Mets are my boys.”

As I left the theater I heard a burst of applause. That was for Pat walking out on stage. It was so loud, I wondered if maybe he’d tripped coming out from the wings. That would be a good Met play.

I took a cab back to Manhattan and out to the Polo Grounds. In the dugout I cornered Ed Kranepool, the Mets’ eighteen-year-old infielder-outfielder who’d been given an $85,000 bonus to sign with the team. It was easy to pick him out from the “shop-worn” veterans: he was the one with the peach-fuzz on his cheeks, the one who doesn’t shave.

I showed him a picture of Pat, explained to him that the actor-singer was “adopting” him, Casey, Piersall and the other Mets.

I asked for his reaction.

A big grin creased his face. He said, “Please tell Daddy to send me my allowance.”

As I write this I’m also watching the Mets on TV. Ed Kranepool’s no longer with them; he’s been shuffled off to Buffalo for further seasoning. The Mets have lost ten straight games and are trailing in the eleventh. But we’re not licked yet. The miracle can still happen. Maybe we’ll lose only 119 games this year.

Sometimes, when I’ve had a few beers, I open to the sports page, turn it upside down and read the standings of the clubs. That way the Mets are on top.

Gotta sign off now and write to Pat. There’s a rumor going around that the Mets are signing up Bo Belinsky, now that he’s struck out with Mamie Van Doren. Wonder how this fits in with Pat and Shirks adoption plans?

THE END

—BY JIM HOFFMAN

See Pat in “The Main Attraction,” M-G-M; 20th’s “Never Put It In Writing.” His next is “Strictly Personal,” for Seven Arts.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1963

No Comments