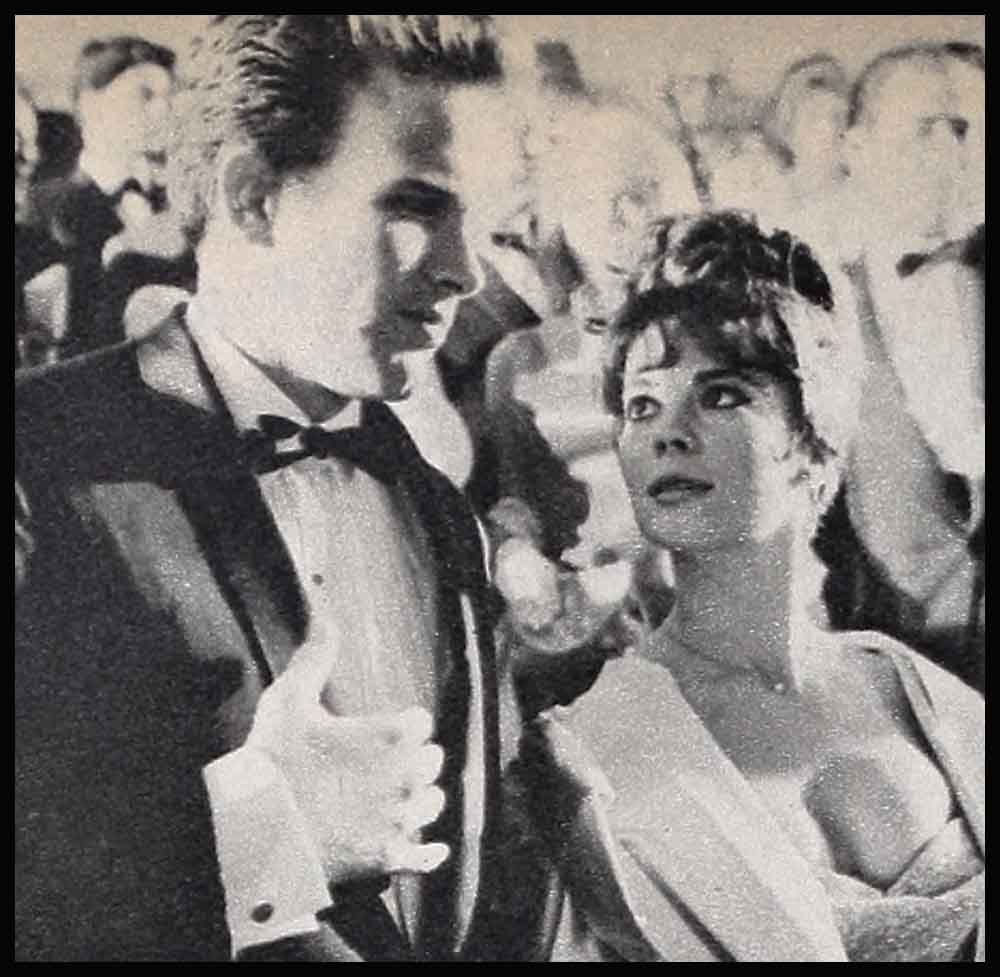

Warren Beatty & Natalie Wood

The way Natalie and Warren are behaving, they’re getting a name for themselves. Rebels. Rebels who try to break out of the bonds of accepted morality, usual rules, traditional laws, and seek another country, a different place, where spontaneous passion is treasured above dullness, where frenzied excitement is honored above habit, where the tension of love is worshipped above the sameness of marriage. Their search for this place of pure sensation seems to obsess them. Natalie and Warren have traveled across this country and throughout Europe together looking for it. Across the border there must be still stronger wine; across the ocean there must be still madder music; across the continent there must be still greater exhilaration; across the city there must be still wilder thrills. All you gotta do is keep moving, moving, moving—faster, faster, faster—away from the restrictions of society and toward that realm of sheer delight to which no two people have ever traveled before. But even though they may feel like pioneers, Natalie and Warren are actually followers. Blinded by their emotions as they leave the well-worn road of convention and morality to blaze what they believe to be a new trail into the wilds of unfestricted freedom, Natalie and Warren cannot see the wreckage left along the path by all the previous rebels against society who have traveled along this same route before. Wreckage left by Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rossellini. By Deborah Kerr and Peter Viertel. By Ava Gardner who journeyed along this trail twice—first with Frank Sinatra and later with Walter Chiari. By Glenn Ford and Connie Stevens. By Liz Taylor and Richard Burton. By Tony Curtis and Christine Kaufmann. By Rita Hayworth—once with Aly Khan and now with Gary Merrill. By Lana Turner and Johnny Stompanato. By Errol Flynn and Beverly Aadland. By Gene Tierney, also with Aly Khan. By Nancy Kwan and Max Schell.

The wreckage of disillusionment and disappointment, the aftermath of running away from society’s codes of conduct and moral standards. And if anyone should have been able to see the warning signs along the way, it was Natalie. For the very man with whom she was running off to Europe (even though her final divorce from Bob Wagner wouldn’t be legal for months and months and months) had already been over this very same path in the past. With Joan Collins. The example was there for Natalie to see—if she wanted to see it.

Joan, too, when she was running from city to city with Warren, and from country to country, had believed that the two of them could defy the world. “Nothing matters when you’re in love,” she said. “We’re not officially engaged yet. But that doesn’t matter either. I trust our love.”

Nothing mattered except Warren. A London news- man reported: “There has never been a fiancee like Joan Collins. To be with the man she loves, she is prepared to miss meals, cross oceans, spend thousands and forego roles.” Joan just couldn’t bear being separated. Once, she walked out on a picture, “Sons and Lovers,” because it was being made in London and Warren was in New York. Another time, she flew across the Atlantic and back again during one weekend (she was making “Esther and the King” in Rome), just so she could sneak in a few hours with Warren. At the Harwyn club, she held Warren’s hand happily as she told a reporter something that her shining eyes had revealed already. “Be sure and say I love him very much.”

But Joan’s “trust” in Warren’s love faltered during one of her trips to New York, when she visited the set of “Splendor in the Grass.” There, watching Warren and Natalie on and off camera, she saw something that Bob Wagner, crazy in love with his wife, couldn’t see or wouldn’t see. And the realization of what was happening made her sick with dread. The trail of excitement that Joan had blazed with Warren finally reached its end the night that Bob Wagner held his customary farewell party for the crew, after shooting had ended on “Sail a Crooked Ship.” Natalie, who traditionally tended bar with her husband at these affairs, didn’t show up for an hour and a half, and when she arrived she was on Warren’s arm. But the two of them left immediately, and didn’t come back until the party was almost over and nearly everybody gone.

Hours later, Bob, Joan, Natalie and Warren went out to dinner together. A strange dinner. Bob was furious. Warren sulked. Natalie was livid. And Joan—Joan looked as if her whole world had fallen to pieces, and as if all the promises and all the assurances couldn’t put it together again.

The wreckage of a relationship, lined in pain on a beautiful woman’s face. But Natalie was too furious with Bob and too involved with Warren to look at Joan and see her own possible future mirrored in the eyes of the miserable girl who had blithely defied convention and said confidently, “Nothing matters when you’re in love.”

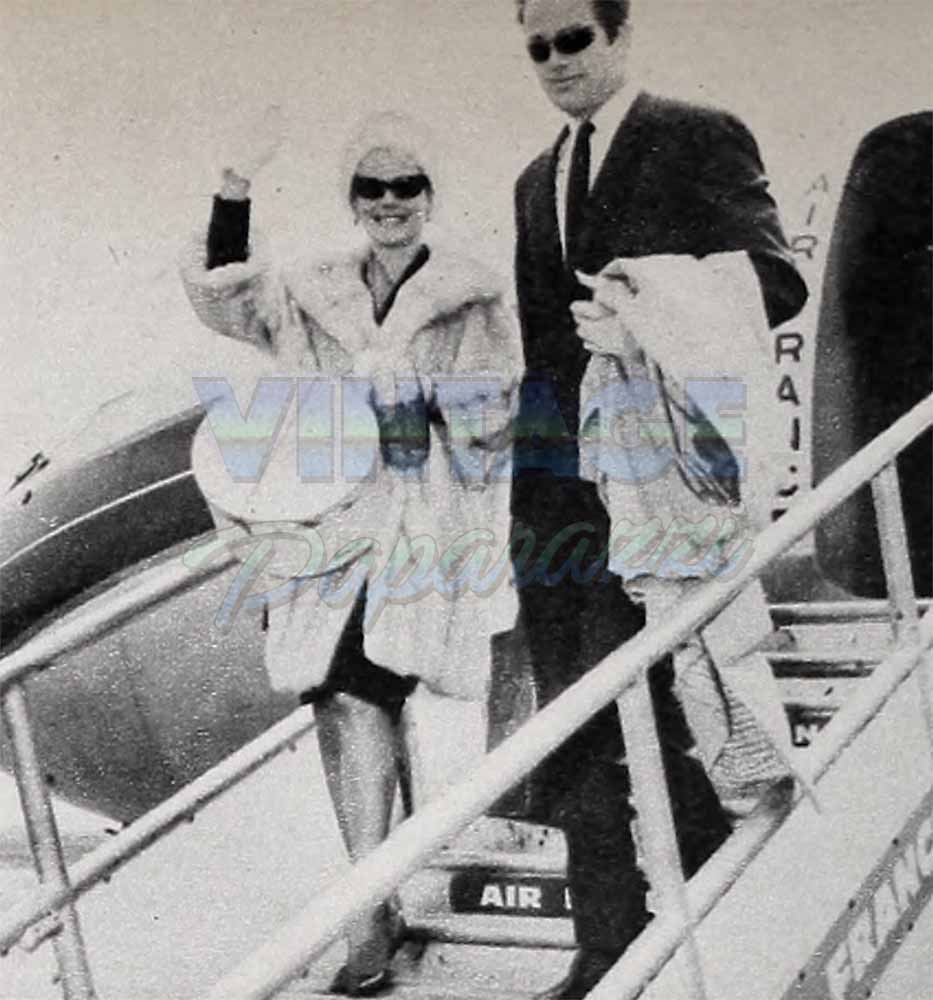

“Nothing matters when you’re in love”—this was to become Natalie’s motto, too: her slogan, her credo, her obsession. She went to New York to be with Warren, to Florida to be with Warren, and then, the day after her “dream marriage” to Bob Wagner was dissolved in a divorce court, announced her intention of going to the Cannes International Film Festival with Warren.

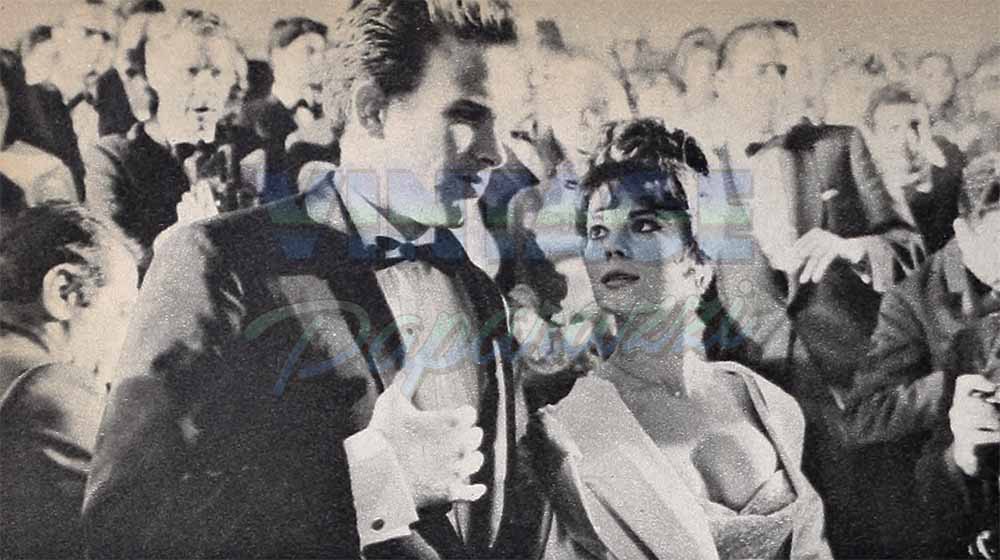

For Natalie this was to be her first trip abroad (Warren, of course, had already made the Grand Tour with Joan), so she had a lot of preparing to do. Like learning French (Suzy in the New York Mirror: “Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty are busy taking French lessons together—that’s the only way to do it when you’re going to Paris together”). Like dining in the Continental manner (Earl Wilson in the New York Post: “Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty were closer than Siamese twins at a feasting at The Forum. Natalie was wearing a low-cut bodice that eased the fears of photographers that she’s a flattie”). Like kissing in public the way European lovers do and most Americans don’t.

On the Continent, Natalie and Warren moved at a whirlwind pace from place to place, as if running away from the normal rules of behavior. At a Soviet reception in honor of the Russian entry in the Cannes Festival, Natalie, with Warren by her side, drank vodka, nibbled at caviar and charmed Communist officials by speaking perfect Russian to them. Somehow her command of their language failed when, after conversing expertly for a while with a Soviet actress, Warren—for whom she’d been translating as they went along—said, “Natalie, tell the Russian lady I find her pretty.” Natalie stammered, faltered, and took over ten minutes to translate his message into Russian.

After this little episode Natalie seemed to stick closer to Warren than ever. Whether she was being entertained by the Aga Khan’s widow, the Begum, or being the guest of honor at a select little party tendered by M. Lebret, the head of the whole festival, she never let Warren out of her sight. It was this constant “watchful” attitude of Natalie’s that prompted Hollywood columnist Dorothy Manners to write: “Some people are beginning to wonder if Natalie’s insistence of ‘togetherness’ with a free soul like Warren is the best technique for this romance. The male is a funny animal. As somebody’s old aunt from Tijuana once said, ‘Keep ’em in sight. But you’ve got to let ’em off the leash now and then.’ ”

With her lips. Natalie had said, “No, I will not marry Warren Beatty,” but the expression in her eyes. when she followed his every movement from across a crowded room, denied her own words.

On Warren’s terms

Warren made no bones about how he felt. At one time or another he said: “Natalie and I haven’t even discussed marriage . . . I love the French. They are more inclined to play with life than fight it . . . I’m confused about marriage. I don’t think I’m ready for marriage . . . I’ve got to be my own boss. I’ve got to make my own decisions. ‘Don’t push me around,’ is what I’m likely to say to anybody who tries to choose for me . . . Right now I’m in my twenties. Those are pretty good years. The important thing for me now is to have a lot of fun. And that’s just what I’m doing … I come and go as I please. Me? I do what I want, when I want . . . That’s the way it has to be—everything on my terms.”

Everything on my terms. When Natalie (at Liz Taylor’s suggestion) went to a Paris coiffeur and had her hair done up in an 1880 chignon, Warren vvas dis- pleased at the results and made his objection clear. Down came her hair over her shoulders, the way Warren likes it.

Time to push on—to Rome. No time to visit the “Cleo” set. however. Too much to do. Visits to historic spots. Trips to the beauty parlor—Natalie dragged Warren along and he waited for her inside while the paparazzi (Italian photographers always on the lookout for scandal) milled impatiently outside. Slow walks through the streets (Warren knew the little, out-of-the-way romantic spots and served as Natalie’s guide; after all, Warren, the free soul, had been in Rome three times in the past, but with somone else, of course). Dining on gourmet food at famous restaurants at night.

But ecstasy is not without thorns. One thorn is the business of staying in separate hotel rooms on different floors. This is right and proper, of course—the accepted procedure for a couple who are unmarried (actually, Natalie’s final divorce decree from Bob Wagner will not be issued until April. 1963), but the paparazzi were bound to try to catch Natalie and Warren together, in his suite or her suite in the fashionable Rome hotel, so as to create a scandal.

This separate suite problem had plagued Warren and Natalie once before. That’s when they also were registered in separate suites on different floors at New York’s Plaza Hotel. while on a publicity junket for “Splendor in the Grass.” Maybe it was the fact that they were together in Manhattan that triggered a blast from Bob Wagner, heartsick in London after his bust-up with his wife.

“I do not believe that this thing between Warren and Natalie just happened,” Bob declared. “I don’t trust that guy. This whole business smells of planned trickery. If Warren needs the publicity so badly, why didn’t he pick on someone else’s wife instead of mine? While he was engaged to Joan Collins, he was going around telling people that he was too young to marry. There is every indication that he never intended to marry Joan. Man, this is one of the wildest ambos (translation: ambitious boys) to hit Hollywood in years.”

That had been the plaintive. truculent cry of the rejected husband. But now it was Bob Wagner, the real-life Bob. not the memory of Bob, who was to be the sharpest thorn in the path of Natalie and Warren, the globe-trotting lovers.

It happened in Rome, in one of those swanky Italian restaurants. Nat and Warren, hand-in-hand and smiling happily at each other, were ushered by a bowing and scraping maitre d’ into an exclusive, private dining room in back. A candlelit, romantic room—a perfect place for an intimate tete-a-tete: fine wine, fine food, and the fine feeling of being alone and away from the world.

Not quite alone, however. Another couple sat close together at one of the tables. The man turned around to look at the new arrivals. It was Bob—Bob Wagner, and the woman with him was Marion Donen, whom he plans to marry when his decree from Natalie becomes final next April.

Natalie’s face turned the color of the tablecloths around her. She stared at Bob and be stared back at her—in embarrassment and shame, like two puppies punished for doing something naughty. Then, though she tried to hold them back, big tears ran down her cheek. She was no longer the sophisticated woman of the world, the rebel against the rules and regulations of society. In that one second she became the little-girl-lost.

It was Warren who broke the spell. He released her arm. clenched his fingers together like a prize fighter about to put on the gloves; then he turned on his heel and stalked out.

Bob and Marion got up quickly and also left.

Natalie stood alone for a second in the middle of the room. and then she slumped down on a chair and sobbed. The flickering candlelight played on her red-eyed, tear-stained face. It was far from a romantic picture. Anything but!

The face of reality

Not a romantic picture, but a familiar one. Similar to the expression that eventually stained the faces of all the women who blithely defied accepted convention.

Similar to the expression on Joan Collins’ face when she realized that Warren would not marry her and that, in fact, she had lost him to Natalie.

Similar to the expression on Ingrid Bergman’s face when—after deserting her husband. Peter Lindstrom, to run away with Roberto Rossellini (who had also left his wife, Marcella de Marchis) following passion that led from Hollywood to New York to Rome to Capri to Sicily and Stromboli—she, lay alone in an Italian clinic, about to give birth to an illegitimate child, while outside her door the nuns fought with the photographers who were intent on breaking in and snapping pictures. Similar also to the expression on Ingrid’s face later when she peeked out through the drawn curtains of the Roman love-nest she shared with Roberto and saw a pile of refuse and garbage piled on the Street in front of the apartment house door. As Ingrid said, “It was meant to show a woman of ill repute lived there!”

Similar to the expression on Deborah Kerr’s face when, after gallivanting about Europe for two years with Peter Viertel while she was still married to another man, she was informed that the price her husband would force her to pay for her transgressions was to give up her daughters, Melanie and Francesca, whom she loved dearly.

Similar to the expression on Ava Gardner’s face when. after a screaming fight with Frank Sinatra in a suite in New York’s Hampshire House hotel, she flung out of the window the diamond engagement ring he had given her.

True, they did get married, but the matrimony—hectic as it was—was an anticlimax to the courtship, and Ava and Frank split up in two years.

Similar also to the expression on Ava’s face, when, after a fight with mild-mannered Walter Chiari in a night club, she bolted out and jumped into a cab, with her escort right behind her. There, through the rear window of the cab, spectators saw her beautiful face distorted into a tear-streaked grimace as she pummeled Walter with her fists.

After a four-year romance that took them to more cities than most people visit in a lifetime, Ava tired of Walter. He still hung around the set where she was making “The Naked Maja,” fetching coffee and cigarettes for her, while she acted as if he didn’t exist. She sees him still—but the passion is gone!

Similar to the expression on Connie Stevens’ face when, after dating Glenn Ford almost every night for a long time and accompanying him to such far-flung and widely separated events as a gala in Washington and a preview of “Four Horsemen” in Europe, she learned one day that he had gone back to Hope Lange.

After his interlude with Connie, Glenn started dating Hope again when they costarred in a film on the French Riviera. They returned from Europe together on the S.S. United States, but wedding bells haven’t chimed for them yet!

Similar to the expression on Liz Taylor’s face when, after she told Dick Burton, “I can’t live without you!” she heard him answer, “If you cannot live without me—then die!” Similar also to the expression on Liz’ face when she read the Vatican paper’s characterization of her relationship with Dick as being that of “erotic vagrancy.”

Similar to the expression on Christine Kaufmann’s face when reporters asked her whether she was going to marry Tony Curtis. She’d been with Tony on three continents—South America, North America and Europe—yet she was forced to admit that she and Tony had never discussed marriage. Then, with the false bravado of a seventeen-year-old girl who is thoroughly confused, she hastened to add that she would be willing to live with a man, with-out benefit of matrimony, if she loved him.

Similar to the expression on Rita Hayworth’s face when in 1952, after three years of marriage to Aly Khan, she told her lawyers in Reno: “Aly has reverted to his playboy self.” To which Prince Aly retorted brutally: “She’s just a homebody. All she wanted to do was slip into some- thing comfortable by the fireside.”

Both parties, of course, were right. The very quality that had attracted Rita to Aly and had led her to accompany him to the capitals of the world before they were married—his daring, devil-may-care attitude towards all rules—became the quality she couldn’t stand in him as a husband; while, for his part, Aly couldn’t understand why a woman couldn’t be his wife and continue to act like his mistress.

Recently, since her fifth divorce, Rita has been capering on two continents with Gary Merrill, ignoring the lesson that her previous country-dropping experiences with Aly should have taught her.

Similar to the expression on Lana Turner’s face that night in Hampstead, a swank London suburb, back in 1957, when Johnny Stompanato—the man with whom she fled from America—beat her and then held a sharp razor to her throat and threatened to slash her beautiful face to shreds.

But the really fatal explosion of violence involving Lana and Stompanato was fated to be postponed until the next year when, on Good Friday night, Lana’s daughter Cheryl heard Johnny threatening her mother. It was then that the fourteen-year-old girl plunged a ten-inch carving knife into Stompanato’s stomach.

Similar to the expression on Beverly Aadland’s face when Errol Flynn died only moments after their last embrace in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1959. The tragic end of a romance that had begun in a hunting lodge on a Hollywood hillside estate when Beverly was just fifteen, and continued in Africa. Paris, the Riviera, Majorca, Spain, England, Cuba, Jamaica and New York—and then finally Vancouver.

Similar to the expression on Gene Tierney’s face when Aly Khan—a familiar traveler on the trail of unconventionality—finally told her, “I cannot marry you.” Yet just six months before, after a whirlwind romance that had been ignited in Argentina and burned brightly in Hollywood, London, Paris and Cannes, Gene had told reporters who had tracked them to their hideaway in Baja California, near the Mexican border, “I certainly consider myself engaged, and we’re very much in love. We will probably be married in six months, I imagine in Europe.”

And as Gene was speaking those words, Aly stood by her side, looked at her lovingly and nodded in agreement.

Expressions of pain, of disgust, of fear, of unhappiness—all similar to the tear- stained look on Natalie Wood’s face.

But what about Warren Beatty? Perhaps his I-can-take-her-or-leave-her attitude towards Natalie is what he believes are his true feelings, but he should consider carefully the example of another free soul who tried to play fast-and-loose with love.

The man—Max Schell. The woman— Nancy Kwan, with whom Max believed he could have a relationship strictly on his terms.

After all, he had already proved that such an arrangement was possible. (Just as Warren, too, with Joan Collins had proved that a man could take—and leave —a woman whenever he wished.) For almost a year a pretty German girl—charming and most attractive—had accompanied him nearly everywhere—from Germany to New York to Hollywood and back to Germany again. But when he was scheduled to make “Judgment at Nuremberg” in Hollywood, he broke off with her forever.

In Hollywood he met the exotic Nancy Kwan. Within a few short weeks, Max and Nancy had fallen wildly in love. But Max, like Warren, can’t stand subterfuge, so he told Nancy immediately that he was not interested in marriage.

The weeks stretched into months, and Max and Nancy were inseparable. But when the publicity firm that handles them both asked them to pose for pictures together, Max refused with a cold, “I do not make love in public!” What Max meant by those words was that he’d not give official status to their romance.

The reluctant Max

Nancy wanted to take Max home to Hong Kong to meet her father, but Max had other ideas. He was going to Europe alone. In his next picture, “The Reluctant Saint,” he was going to play a holy man and he wished to disappear for a while in Italy to live as a monk.

Nancy went home alone. Meanwhile, Max wrote a Hollywood columnist to stop speculating about his marrying Nancy Kwan—it was simply not true. Nancy returned to Hollywood, shocked and hurt. Max, apologetic now, flew to be with her on his one free weekend during shooting.

By the time the weekend was over, he and Nancy had visited the columnist in person, and Max admitted for publication that he loved Nancy deeply—he was only sorry their career commitments prevented an immediate marriage. The columnist beamed, and so did Nancy.

Nancy was still beaming when Max returned to Europe. She was overjoyed when he asked her to be his date for the London premiere of “Judgment,” and again for the Los Angeles premiere soon after. Following those appearances in cities six thousand miles apart, the question everyone posed about the Kwan-Schell , romance was not if the marriage would take place, but when.

But Max continued to make his declarations of independence. One morning Nancy picked up a newspaper and read that Max, in an interview given a day or two before, had laughed off rumors that he and Nancy would be getting married soon. “We are good friends. But marriage? It would be unfair of me to get married now. I don’t want to get married. Marriage takes concentration. Every woman wants and needs attention. I am more interested in giving attention to my work.”

They began to fight, in public and in i private. They fought in Hollywood and in London. They separated and then flew back into each other’s arms. They were miserable together; they were even more miserable apart.

Max was as inconsistent as he was ardent. One day, when a television interviewer asked when he planned to marry, Max answered coldly, “Why not ask me when intend to commit suicide?” Yet almost the next day, it seemed, he gave Nancy a jade engagement ring.

Only Max refused to indicate that he was ready for marriage; he still dawdled and dallied, alternating declarations of love with declarations of independence, insisting that the romance be conducted on his terms.

Max came over from Munich to visit Nancy at Innsbruck where she was on location making “Main Attraction.” Then he took time out to fly from Switzerland to California to collect his Oscar as best actor of the year, secure in the knowledge that Nancy would be waiting for him.

But this time Nancy wasn’t there. She had left for the weekend to see an Austrian ski instructor, some fellow named Peter Pock, and Max was furious. So furious, in fact, that he left Innsbruck as fast as he could, leaving the Oscar behind in the rush.

And so they were married. Not Nancy Kwan and Max Schell. but Nancy Kwan and Peter Pock. And it was the ski instructor from Austria rather than the actor from Germany whom Nancy finally brought home to meet her parents in Hong Kong.

What about Max, the man who demanded romance on his terms? Well, Dorothy Manners reports, “Maximilian Schell has gone into a clam-like silence regarding any comment on Nancy Kwan’s sudden marriage to Austrian ski instructor Peter Pock . . . But no matter how glacial his exterior, the few close to Max believe the Oriental beauty gave him a big jolt right under his ribs on the left side—where it hurts.” And Sheilah Graham declares, “Unhappiest man in Europe is Max Schell since the girl he loved so long, Nancy Kwan, married that Austrian skiing teacher. Max waited too long—he thought Nancy would always be there. There’s a big moral here.”

A “big moral”—one that Warren Beatty, another free soul, might well ponder.

Just as Natalie Wood, now back in Hollywood with Warren, should take a good look at the wreckage strewn along the trail to ecstasy by other women who have left the tried-and-true road of convention to travel that path before her.

—JAE LYLE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1963