The Trials Of Jean

OUTSIDE A BUILDING just off Broadway in New York City, on a brisk October morning, early-bird traffic was in its usual snarl. Producer-director Otto Preminger was in one of the creeping cars, on his way to supervise the final tests to find the actress for his “Saint Joan.” It was time and more than time for his decision. The search had been conducted through movie houses and magazines. Eighteen thousand girls had applied. He’d spent five weeks on the road, here and abroad, himself seeing three thousand of the candidates. Yet the industry wiseacres still didn’t believe that he was going to cast an unknown. He could understand their skepticism. “Joan” was to be a million-dollar production. He would be gambling a fortune on an amateur. Then there was the matter of the tight shooting schedule. Production would begin in January, finish in early March and the picture would have its first showing in May. The girl he chose would have to have more than talent. She would need, in one plain, unvarnished word, guts. On a set Otto Preminger was known as a merciless perfectionist. On “Saint Joan” he could be nothing else. He had no choice. Too much was in the balance.

AUDIO BOOK

But even a merciless perfectionist could be troubled by a conscience. The Seberg child he’d seen in Chicago, for instance. Something in his mind had clicked; he knew at once that she was a possibility. And so, rehearsing her for her test, he’d been rough, shouting at her, bullying her until she was nearly hysterical. He’d called her a ham, a phony, told her she couldn’t act, couldn’t take it. And suddenly she’d whirled, faced him. At that moment she could have been Joan of Orleans herself, glaring at the whole of the English army, her tone as deadly as a French sword. “Mr. Preminger,” she had said, “I’m going to rehearse this scene until you drop dead!”

There was a tiny, reminiscent smile on Otto Preminger’s lips as the car stopped in front of the building and he got out.

Upstairs, a girl sat alone in a large, bare room. Sat stiffly, like Alice trying desperately to satisfy the Red Queen. In her hand was a small bunch of violets which she had bought just outside the building, on her way up. Somehow they made her feel better.

She was early. Awfully early. “You’re the first,” the watchman had smiled sympathetically when he let her in. She guessed that he’d seen a lot of girls come in for screen tests.

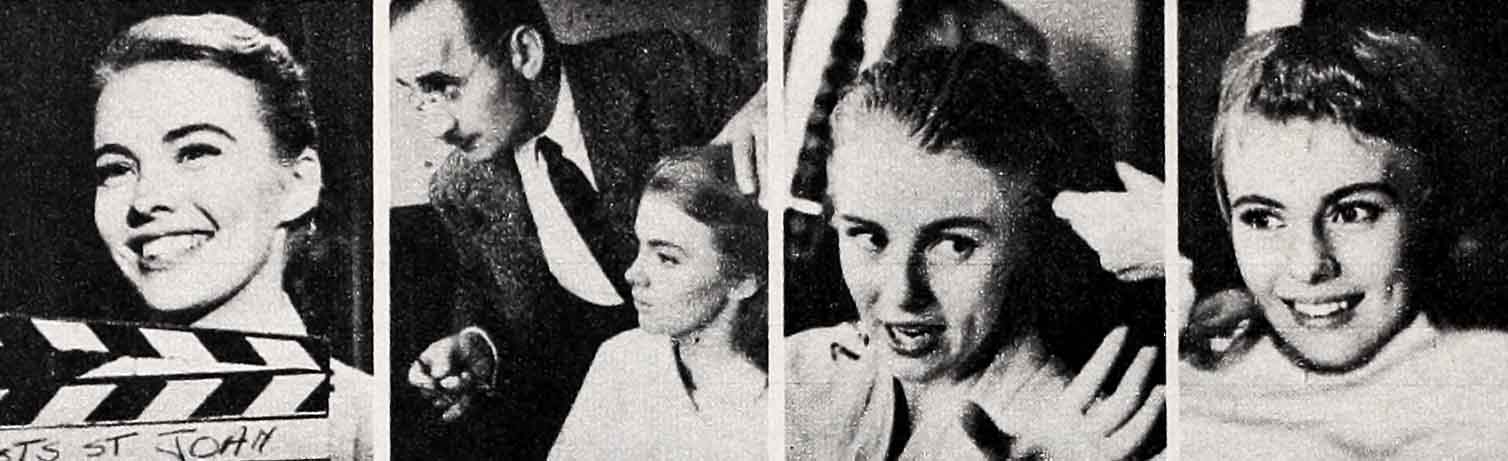

She’d been so afraid she might be late. But now she was glad she would have some time to herself, before the others came. In a few hours the room would be busy and she’d be in front of the camera. First she would give her name, her age, her hometown, her ambition. Easy enough, if she could keep her voice steady. “My name is Jean Seberg. I’m seventeen years old. I come from Marshalltown, Iowa, and I want to be a very good actress.” Just the facts, none of the dreams.

Then she would do the scene from ‘‘Saint Joan.” Not so easy.

She leaned back in the chair and tried to relax, but her mind wouldn’t stay still. What time would it be in Iowa? Dad. Mother. Grandma. Mary. Kurt. David. Were they thinking about her? Of course they were. They were waiting and wondering, too. “I go do it by my lone . . .” It was the first sentence she’d ever spoken and her mother said it was prophetic. She was the one who was always off on some tangent or other—by her lone. But she’d never before been quite so far away.

She’d always wondered how her parents managed to survive her childhood, through the tomboy stage, when she must have been a terror. They hadn’t cracked a smile when she’d decided to become a brain surgeon and save the world. They’d watched her study the anatomy books she borrowed from the doctor, and listened while she recited the sections of the brain. And they’d gotten pretty good at dodging when she took up bullfighting and practiced with the dishtowel in the kitchen.

She was well on her way to setting a record for borrowing books from the public library, so they hadn’t been surprised when she’d come home with the two volumes on the Stanislavsky method of acting. She was thirteen and had seen Marlon Brando in “The Men” and she’d gone straight to the library from the movie. She couldn’t get through the books and took them back the next day. But after that she’d never doubted that she’d be an actress. It was a phase she hadn’t grown out of. And it puzzled her family.

Sometimes she wished she could be more like Mary. Mary was twenty and gentle and sweet and domestic, the nicest sister in the world. Smart, too. She’d made Phi Beta Kappa at Iowa state. There was probably only one girl in Marshalltown who had had the chance to go to college and didn’t want to go. Jean Seberg wanted to go to New York and try for Broadway, even if she had to starve in the process.

Well, here she was. She’d been nervous at the reading in Chicago, but it hadn’t been quite like this. She hadn’t expected anything to come of the reading. Her mother had met the plane when she came home from summer stock and brought along a letter from the Otto Preminger Office. The letter said that if she liked she could come to Chicago and audition for Mr. Preminger.

The search for “Saint Joan” was a publicity stunt, of course. She couldn’t imagine why her elocution teacher had bothered to send in her name. Still, the audition would be good experience; she might learn something.

Later, someone told her there were two hundred and fifty girls in the auditorium. She just knew that they all seemed to look like Ingrid Bergman or Audrey Hepburn. One by one they had stepped up to begin the “perpetual imprisonment” scene. “Perpetual imprisonment! Am I not then—”

“Thank you very much,” said Otto Preminger.

And Jean Seberg sat with her mother and thought, “Please make him listen to me—”

Her turn came. The director asked her name, her age, and then, “What are you doing now?”

“Trying to get out of going to college,” she’d blurted.

She’d kicked off her high heels and started the scene. He’d listened. He’d given her a screen-test contract. She was flown to New York to read the whole play, flown home again. Two weeks later, she’d returned to New York. There were two other finalists, a girl from Stockholm and a girl from New York City, and they’d studied for the tests together.

And here it was. This was the day they’d been working for. . . .

“Let me get a picture before you strangle those violets!” The girl in the waiting room off Broadway looked up and saw photographer Bob Willoughby grinning at her. She grinned back, sheepishly. She hadn’t realized she was holding the flowers so tightly.

Bob Willoughby had been assigned to photograph “Saint Joan” from beginning to end. He’d met Jean Seberg in Otto’s Office one day and hadn’t been especially impressed. She was a small girl, with a mop of hair that came to her shoulders and made her look a little mousy. At the moment she looked lonely, too, and it was getting close to noon, so he asked her if she’d like to have lunch with him.

He asked her if she’d ever been to Greenwich Village. She shook her head. “Ever been to Paris?” he smiled.

“I’ve never been anywhere.”

In the Village, he bought her a little silver cross, for luck, and she came alive, glowing with pleasure, as though it were a Winston diamond.

So went the day “Saint Joan” was chosen. It was a tense, tiring day, and it wasn’t very glamourous. But the undercurrent of excitement that ran through it made it memorable, one Jean would never forget. One of Preminger’s staff says, “The other two girls were very talented. Their work had gloss. They knew acting tricks that Jean would have to learn. The little mouse was less professional. But when she started to act it was as if a switch had been turned on. Something electric came through. Tony Perkins has that kind of quality. Jimmy Dean had it. When we watched Jean, we realized what Otto Preminger had seen, back in Chicago—”

The day dragged on into the afternoon. Then Otto announced that he would look at the rushes, and if he wanted any more footage he would call the girls in on Friday. Jean prepared herself to wait. She supposed things had gone all right. She couldn’t seem to tell anymore. “I was in my dressing room when Mr. Preminger came down,” she remembers. “He saw the violets and asked who had given me the flowers. ‘Nobody,’ I told him. ‘I like flowers and I bought them.’

“ ‘I’ll send you flowers the day you start the picture,’ he said.

“I knew I had the part. I felt wonderful and frightened and terrible. Terrible about the way I’d spoken to him at rehearsal. I’d never hated anyone before in my life, but I had hated him that day. And when I talked back to him the way I had, I’d been proud of myself. I’m ashamed now. I know now that it was important for him to find out if the person he chose could take criticisim.”

Jean Seberg began her new life. They cut her hair and it seemed to give her face new strength and amazing new beauty. They told her how to wear makeup. Then they let her go home to see her family for four days.

She’d never imagined such a homecoming. The governor of Iowa himself met her at the airport and presented her with a golden ear of corn. The city of Marshall-town gave her a watch. Flashbulbs flashed, TV cameras ground away. There was a parade through the main street, with “Welcome Home,” and “We’re Proud of You” signs in windows. There was an eight-foot painting of her head on a building front, and the head on her shoulders began to spin. Friends called and stopped by the house, the press came in from Des Moines. There were television appearances, magazine layouts. And in the midst of it all, she realized she’d hardly had a chance to see her family. She hadn’t reckoned with this side of fame.

Then there were goodbyes. She was the baby girl and it was hard for her family to let her go. But at the airport her mother smiled, “I guess all along you’ve been getting ready for something special to happen to you.”

Back in New York, she began to wonder if she was ready. The studio had set up a press brunch, she learned. She’d read interviews given by actors and actresses, but it was one thing to read about them, another to give them. What would they ask? What would she say? On the way to the brunch, Otto Preminger saw that she was nervous.

“There’s something I’d better tell you now,” he said. “Your parents will be there.” He’d flown them to New York to surprise her. But he was afraid the surprise would be too much for her.

While members of the press watched her screen test, Jean stayed in another room. “Suddenly,” she says, “a hand reached out and grabbed my arm and led me into the room where the reporters were. There were about a hundred and fifty of them. Flashbulbs were popping, my parents were shoved up beside me. Mother’s eyes were still a little damp. She told me she’d cried through the test.

“Richard Widmark was there. It was the first time I’d met him, and he told me he was shy about press conferences, too. I was terrified. There were so many people and so many questions, all at once. ‘Shall I tell the truth?’ I whispered to Mr. Preminger.

“ ‘Always tell the truth,’ he said. Then he looked out over the crowd and smiled. ‘They’re very nice people—individually,’ he said. And everyone laughed.”

After a short time in New York, the girl who had never been anywhere left for London. She was given a suite at the famed Dorchester Hotel, which was to be her home for the next four months. once her clothes were in the closet, she reached into her suitcase and took out the other things she’d brought from home, the gifts from people she’d never met. A medal which had been blessed by the Pope from a Catholic girl. And a Jewish medal, given to her by the Irish maid in the New York hotel.

There was the tiny figure of a knight, which had come with one of her first fan letters. “Dear Jean,” the little girl had written. “This little night [spelled just that way] I found in my breakfast food. I hope it brings you good luck.” And then there was the scrapbook of her life, a gift from the first graders in Marshalltown. They’d drawn the pictures. Jean as a baby was the first one. The last was Jean as Saint Joan, on her horse. They’d all signed their names and she hoped they could decipher her thank-you note. She’d printed it because she knew they couldn’t read longhand.

She put the scrapbook on the desk and sank down into a soft, deep chair, and fingered the silver cross around her neck—

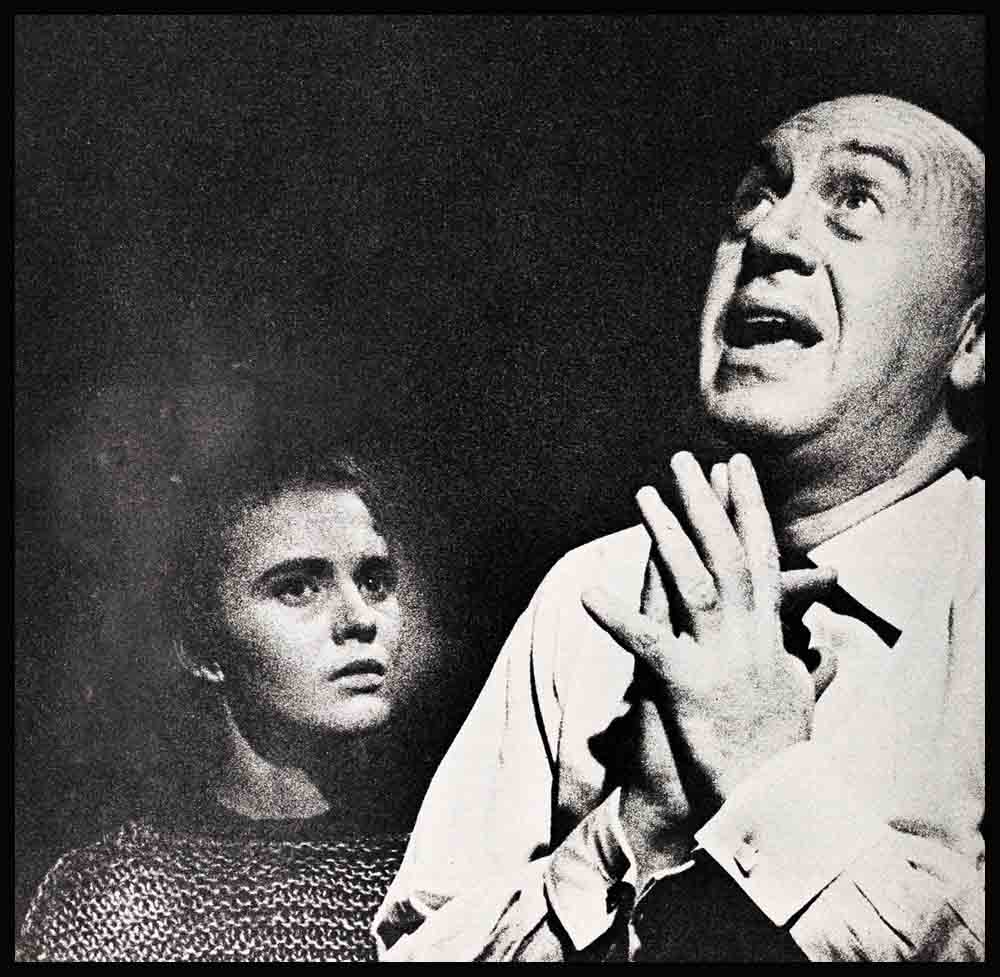

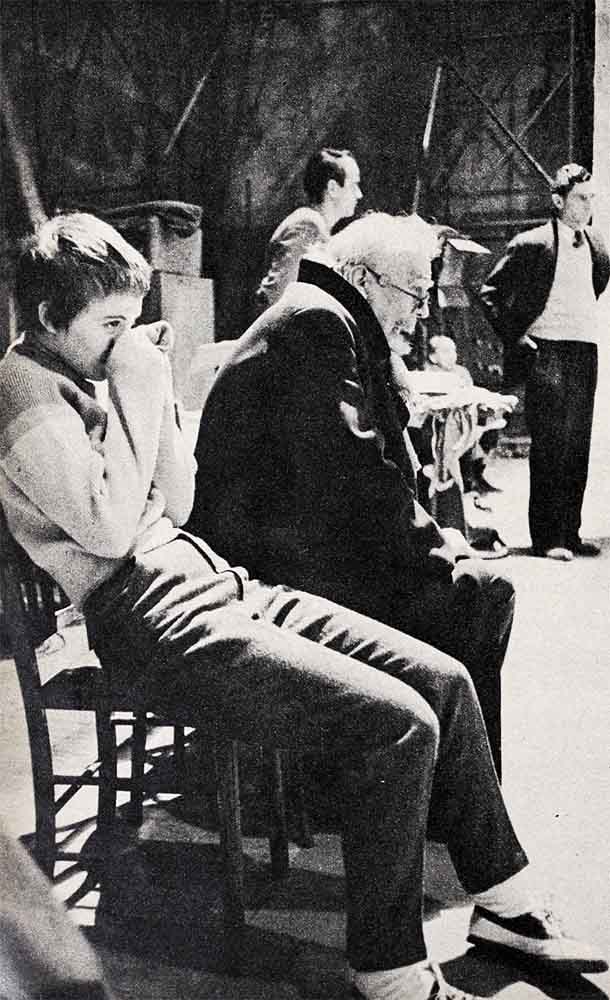

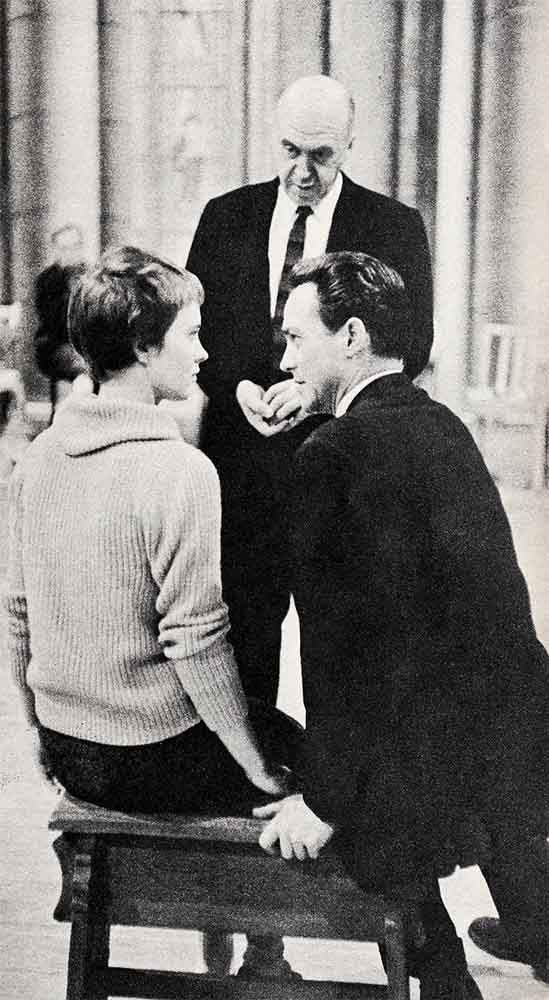

The next two weeks were full ones. She took riding lessons and French lessons. There was a London press conference, and this time there were five hundred guests. And then Otto Preminger called for a reading of the script. It would be the first and perhaps the only time that the complete cast of principals would be together. They sat at a board-meeting type of table, with Preminger at the head, Jean at his right, Dick Widmark at his left.

The schoolgirl from Marshall-town, Iowa, faced the cast of veterans, the cream of the English stage and movies. Sir John Gielgud, Richard Todd, Anton Walbrook, Finlay Currie, Barry Jones, Margot Grahame, Felix Aylmer. “I felt that they wouldn’t have taken the risk of putting an unknown into such a big picture unless they were confident she would do well,” Gielgud remembers. “But what a terrible ordeal for that girl, reading in front of all of us.

“It was a small room and it was crowded. They were doing a documentary on the filming and there were lights and cameras. In addition, there were a lot of publicity people around. It was enough to make an experienced actor terribly nervous. It must have been a deathly ordeal for Jean.”

Jean had a script in front of her, but she didn’t use it a great deal. Both she and Dick Widmark knew their lines. “It was obvious,” Gielgud says, “that she had a very good natural emotional quality—”

Rehearsals followed. Dick Widmark would come by the hotel and they would rehearse for the rehearsals of their scenes together. As a crew member put it, “Otto just pounded Jean on the head day after day and she responded to what he wanted.”

With Christmas coming, Preminger knew that his new star would be a homesick star. He thought it would help if he announced his gift early in the season. “I can’t put it under the tree,” he told her.

The gift was a trip to France. Two days before Christmas, they clipped her hair to a length even shorter than a crew cut, after which Jean, Preminger, American newspaperman Tom Ryan and Bob Willoughby flew to Paris. Preminger arranged a meeting with Ingrid Bergman, who laughed and said, “Saint Joan’s hair seems to grow shorter every generation.” And then, growing serious, Ingrid told Jean that the role of Saint Joan was “the greatest, finest woman’s part in the world.”

Another highlight was a visit to Dior’s, where Preminger bought her an evening gown. If she felt less glamourous than she’d dreamed she might feel, it may have been due to the personnel’s parting request. “They asked if I’d please promise to wear a wig when I wore their dress,” Jean grins.

On Christmas Day, Jean stood in the house where Joan was born, in Domremy. She saw the market place at Rouen, where Joan was burned, and the river into which Joan’s ashes were thrown. The things she felt then were hard to put into words. “She was pretty quiet and reserved that day,” says Bob Willoughby. “She seemed reverent about the trip. She felt it.”

In London again, there were more rehearsals. And finally the initial day of shooting. There are two different versions about that day. Both correct. “Even on a minor production there’s nervousness the first day,” says a publicist who was there. “People have to shake down and get to know each other, preferably without outside interference. But this was a big new film and a new girl. It was news, and Mr. Preminger gave permission for a press call.

“They all came, forty or fifty reporters and cameramen adding to the pressure of the first day of shooting Jean had ever had in her life. But she was amazing. In between shots she came off the set and talked to the newsmen and gave them her absolute attention. When they wanted a shot of her thrusting her sword, she answered, ‘It’s not typical. Joan doesn’t fight, you know.’ She was thinking. And she was in absolute control of the situation.”

Jean has another memory. “The first scene was the courtroom scene with the Dauphin. It was the first time I’d ever seen a movie set in action and it was terrifying. The lights didn’t bother me so much, but those cameras! They looked like big cannons, aimed right at me.

“And the press. It seemed as if they all came at once. I barely remember what I said to them. But finally I said, ‘I have to go,’ and ran away. I just couldn’t take it.”

Bob Willoughby confirms both accounts. “One of the actors, Patrick Barr, took her by the hand and led her over to the press. She sat down in a chair and I was surprised at how calm and assured she seemed. Then I happened to walk around behind her. Calm, my foot. She had one hand in back of her and was hanging onto Patrick’s hand for dear life!”

It might be said that Jean Seberg led a double life during the production. She was the girl who bumped into Sir John Gielgud in Otto Preminger’s office soon after she arrived in London and found herself momentarily speechless. What should she say? What should she call him? Mr. Gielgud, Sir John, John? Finally she settled for, “How do you do, Sir John Gielgud,” and retreated into the nearest corner.

She was also the girl of whom Gielgud said, “She has beautiful manners and she’s very modest. But she isn’t too deferential. She doesn’t appear to be afraid, and that makes her much easier to talk to. She’s interested in a great many things and she doesn’t talk about herself, which is nice. I like her for that. Then, too, I like her for the fact that she doesn’t try and pick anyone’s brains. She watches and listens.”

Each time Sir John did a scene, Jean was on the sidelines, watching and listening. He brought her candy bars and asked her about Elvis Presley and taught her to work English crossword puzzles. He asked her to his home for dinner one evening so that she could meet Dame Peggy Ashcroft, another English theatre great.

Everyone went out of their way to make her feel at ease. Another evening, production designer Roger Furse invited Jean and Preminger to his home to dine with Sir Laurence and Lady Olivier. Even before they were introduced, Sir Laurence spoke to Jean. “I don’t need to ask you how it’s going,” he smiled. “I’ve asked everyone else and they say it’s just wonderful.”

They all knew what she was going through. “She’s a gifted little actress,” said Richard Todd on the set one day. “But she’s under a tremendous strain. It’s not easy to jump into one of the all-time classic roles.”

The kidding on the set helped. Todd told her about the union that the “youngsters” had formed. Finlay Currie was president, since at seventy-nine he was the “youngest.” “We always work according to union rules,” explained Richard. “Anyone who does a scene in one take is dunned out of the union. Anyone who comes in knowing his lines gets a black mark.”

It was doubtful that she was eligible for membership. In the first place, she was too young. And in the second place, she knew all of her lines, letter perfect, each day.

Then there was the day the picture’s scripter, Grahame Greene, visited the set. Jean pulled up a chair to listen to a discussion between Greene and Felix Aylmer. “One of the things that comes out in the records is that Joan was a very attractive girl,” Greene was saying.

Aylmer shot Jean a fond glance. “Obviously a case of miscasting,” he grinned.

The jokes did help, but there was still the strain. Jean was up at five-thirty each morning. The hotel packed a lunch basket for her and filled a thermos with coffee. At six-thirty, she climbed into the back seat of the studio car and stretched out. The driver covered her with a blanket and she’d sleep until they reached the studio an hour later. She was on the set at eight-thirty. Nights she’d return to the hotel, sometimes as late as eight p.m., a tired figure, wearing slacks, a duffle coat and a corduroy cap, carrying her empty lunch basket and thermos. The manager was there to greet her, “Did our movie star work hard today?” The elevator boy: “How do you feel?” And the maid who opened the door to her suite: “You look tired, dear.”

She’d head for her desk and find her mail. Her family wrote three times a week. Every two weeks she called home and sent clippings. Grandma was the keeper of the scrapbooks, was starting on the seventh volume. Preminger had given her a record player and she’d turn it on first thing. He’d taken her to some small art shops and she’d bought a Picasso print, “Child with Dove.” He’d had it framed for her and some nights she’d come in and play soft music and sit and look at the picture. “The expression on the child’s face is so peaceful,” she says. “Just looking at it makes me feel peaceful, too.”

Tired? She was beat. “The first three weeks I had a terrible time,” she says. “I’d get so tense and the tension would go to my neck and my neck would get stiff. And I couldn’t seem to breathe except in gasps.

“I cut out social life completely when we started filming. I was usually in bed at nine. It wasn’t a sacrifice. I was so exhausted I couldn’t go out. I guess every scene was difficult for me because I was nervous. But the trial scenes, especially. They were so depressing. I couldn’t shake off the mood. It wasn’t as if I’d done a hard day’s work and could forget it. I just couldn’t shake it off—”

There were scenes that went well on the first try. But the others were the ones that haunted her. Off the set, Otto Preminger was a friend, someone she could confide in. On the set, he was the perfectionist. “You were as cold as a cucumber. The whole scene stank. There was no freshness, nothing. It was the most mechanical reading of lines I’ve ever heard. You aren’t thinking. You aren’t thinking. You aren’t thinking the part—”

A publicist who was late in starting to work on the picture had heard stories from the set. “When I met Jean,” she says, “one of the first things I told her was my reaction to Mr. Preminger. ‘Why, he’s very civilized,’ I said.

“I guess I sounded surprised, because right away Jean began to talk, to convince me that the methods he used on the set were all in a good cause. She’s an adult child. She understands what it’s all about. Even when he made her cry she bore him no malice because it was what was needed.”

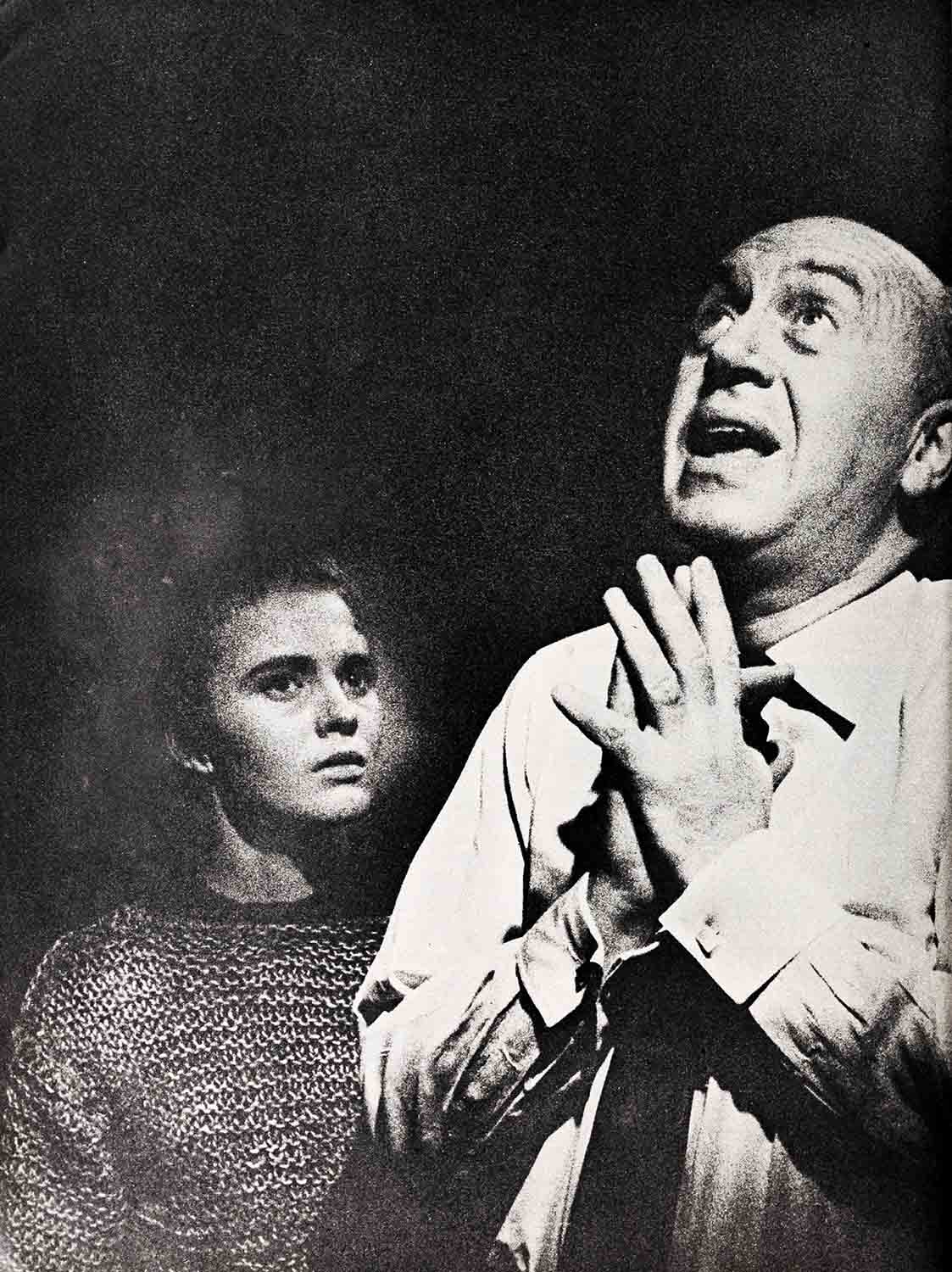

In addition to everything else, there was the fire accident. The day Saint Joan was to be burned at the stake a press call was sent out. There were to be twelve hundred extras, the largest number ever gathered on an English soundstage. Jean was chained to the stake from the neck down. Wood was piled beneath her feet and under the wood were gas jets. She felt no danger, as there had been two days of testing the arrangement. They turned on the gas.

Preminger called for action. The fire was lit. Later they found that too much gas had gathered in the jet directly in front of Jean. The flames roared up around her. Her hair caught fire. She managed to drop the cross she was holding and work her arms free from the chains and cover her face with her hands. The shirt began to burn around her waist. She’d read about what flashed through people’s minds when they thought they were going to die, and she thought, “Am I going to die now? I don’t want to die.”

The two executioners were the only ones on the set who knew how to unfasten the chains. They were the first to realize what. was happening and the first to reach her. Studio firemen turned the fire extinguishers on her. An assistant director jumped up and put his hands in front of her face.

Everyone else was helpless. Preminger was up on the camera crane; jumping down would have meant jumping directly into the fire. Tom Ryan was on a tower. Bob Willoughby was on a ladder. He had his camera, but he took no pictures. The movie cameraman let go of the action camera. By itself, the camera panned over into the crowd of extras. Their expressions had turned from make-believe horror to real horror. Some of them became sick; others hysterical.

When the executioners released her, Jean was led to her dressing room. A doctor was called and dressed the burns on her hands and knees and stomach. “For being so unlucky I guess I was lucky,” Jean said.

“Lucky?” someone echoed.

“It would have been worse if I hadn’t been chained,” she said. “I would have fallen directly into the fire.”

And there was more to come. The next morning, she climbed into the car to drive to the studio with Preminger, Ryan and Willoughby. “The doctor had told me to stay in bed at the hotel, but I couldn’t. I just couldn’t stay there alone.”

They all tried to joke. Someone referred to the previous day’s “barbecue” and Willoughby admitted he was ashamed of himself for not having been able to take pictures; it was very unprofessional. It was a cold morning and there was ice on the road. Halfway to the studio the car began to skid. The driver became frightened and started to let go of the wheel. Preminger grabbed his arm and made him hold on.

The car spun around, making two complete turns. Tom Ryan grabbed Jean so that she wouldn’t be thrown down. Then the car hit a lamp and they were both thrown to the floor. Preminger jumped out of the front seat, came around and scooped Jean up. He had no remark appropriate for the occasion.

Other studio cars came along and picked them up. Willoughby climbed into one that promptly had another crash. He decided to go home and go to bed. With burns, bruises, cuts and a nosebleed, Jean went to the studio.

That evening, she went to watch the rushes of the burning at the stake. And the events of the past two days caught up with her. “I heard the fire extinguisher,” she says. “Evidently that was the only thing I heard when it happened. I went to pieces.”

She had a weekend to rest. On Monday she was back on the set. “I’ve never seen women as tough as American women,” said publicist Susan Storer. “I don’t mean a horrid toughness. I mean—well, courage, for one thing.”

Now things were becoming a little less frightening for the schoolgirl from Marshalltown. She could kid, and she was getting pretty good at comebacks. When Otto Preminger appeared in an exploitation trailer and fluffed his lines, Jean remarked, “You weren’t thinking. You weren’t thinking the part!”

“Hmmm,” said Preminger. “This girl’s been pretty fresh ever since she got burned. She thinks nothing else can happen to her.”

“I don’t know,” grinned Jean. “I guess I could fail into the pond with my thirty-five pounds of armor.”

When the press visited the set, she knew what to say to them, the kind of material they would want. And she could start right in: “I was born November 13, 1938. I’m the second of four children. I have an older sister and two younger brothers, and my grandmother lives with us. My father’s a druggist and we live in a big two-story stucco house.

“I always had animals around rather than dolls and things when I was growing up. When I was in the fourth grade, I wrote a play for Be-Kind-to-Animals week and won first prize. The prize was a puppy, but I never collected it. I had a dog at the time—he’s still living—and I didn’t want to hurt his feelings.

“I wrote several plays when I was in grade school and directed them myself. I took speech work in high school and appeared in plays and won several prizes. In senior high, I played Sahrina in ‘Sabrina Fair.’ It was our big production. We played to a thousand people.

“I did student government work and was a lieutenant-governor at girls’ State, then went to girls’ Nation in Washington, D. C. We didn’t get much accomplished though. There was a lot of dissension between the North and the South!

“I graduated from high school last spring and my elocution teacher recommended me for summer stock at the playhouse in Cape May, New Jersey. I played Claudia in ‘Claudia’ and Mrs. Carroll in ‘The Two Mrs. Carrolls’ and Madge in ‘Picnic.’ But I didn’t look like Kim Novak, darn it.”

Still, there were some things she couldn’t talk about, things that worried her. She’d heard that when people became movie stars their old friends were hesitant about keeping up the friendships. She didn’t want that to be true. She found herself being careful about the letters she wrote. When she said in a letter that she’d had dinner with Sir John Gielgud, it sounded as if she were name-dropping. She never mailed the letter. She’d wait until she got back. Telling them in person would be different.

They’d been behind her all the way when she was testing for “Saint Joan.” They were more confident than she was that she was going to get the part. Some of them were talented kids, waiting for their break. She happened to get hers first and she didn’t want it to make a difference.

And what about love? She’d thought she was in love twice, but she knew she was young and fickle and spoiled. Would an intelligent, respectable young man have too much pride to get involved with an actress who loved her work? She thought of actresses who had happy marriages, and she could only hope that someday she’d be as lucky. Then, too, she thought of the letter she’d received from an older fan. “Someday,” he’d written, “you may have the fortunate difficulty of deciding whether to become a great actress or a great woman. I hope you decide to become a great woman.”

But what about her acting future? And what would happen to her in Hollywood? On the screen, she knew, some stars were “sold” on the basis of glamour. Others on the basis of a great performance, the result of years of training. “I don’t have any technique or training yet,” she found herself thinking. “All I have to ‘sell’ is myself. People say that Hollywood is superficial. If I lose myself by being around superficial things, I’ll have nothing—”

She talked to Otto Preminger about her fears and he told her that for every phony in Hollywood, there are any number of very fine and very real people. But would she ever get to Hollywood? Newspapermen were asking Mr. Preminger about her next role, and he was saying that he had no immediate plans for her. The papers were wondering out loud about who would play the young girl in his production of “Bonjour, Tristesse.” Deborah Kerr and David Niven had been signed for the other leads.

She wanted the part because it was a great part. But she wanted it, too, because it would mean that she’d done a good job in “Saint Joan” and that Mr. Preminger had confidence in her.

It was on a Friday night that Jean and some of the production people climbed into the car to drive into London. A few minutes later, Otto Preminger came out of the office building and got into the front seat beside the driver. As the car rolled past the studio gatehouse, he turned to Jean. “I’ve given Ed Sullivan permission to announce your next role,” he said.

It meant she would play the part in “Bonjour, Tristesse.” There were congratulations and there were jokes. “You’ve lost so much weight, I thought you’d be playing Gandhi,” somebody said.

As the car neared London, the talk died out. Preminger glanced back at Jean. She was sitting in her corner, with the lunchbox and thermos on her lap. It had been a hard day. But, then, most of the days had been difficult for her. With more experience, he knew, she’d learn to relax—then things would be easier for her.

The car stopped for a traffic signal and the light from a street lamp shone through the window. It shone on her face. The face of a future star.

THE END

PLAN TO SEE: Jean Seberg in United Artists’ “Saint Joan” and Columbia’s “Bonjour, Tristesse.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1957

AUDIO BOOK